FIGURE 7-1 Life cycle of a record.

Practice Note

Practice Note

Records have a life cycle that begins with creation and ends with disposition.

Categories of Records

The administrative assistant must be able to decide which records to keep, how to organize and store them, how long they legally must be retained, and when to dispose of them. In general, records can be categorized as vital, important, useful, or nonessential and as active or inactive.

Vital Records

Vital records are essential documents that cannot be replaced. These include patients’ clinical and financial records and the office’s corporate charter and deed, mortgage, or bill of sale. These records should be kept in a fireproof, theft-proof cabinet or safe, and copies of financial records and legal papers are often kept in a protected offsite location.

Practice Note

Practice Note

Vital records are essential documents that cannot be replaced.

Important Records

Important records are extremely valuable to the operation of the office, but they are not vital. They include accounts payable and receivable, invoices, canceled checks, inventory and payroll records, and other federal regulatory records. Such records may be needed for a tax audit or if a question arises about a financial transaction. Important records generally should be retained for 5 to 7 years. Most offices keep them for about 7 years or in accordance with federal or state regulations.

Useful Records

Useful records include employment applications, expired insurance policies, petty cash vouchers, bank reconciliations, and general correspondence. This category is difficult to define, because one office may consider a document useful, whereas another might find it indispensable. These records are usually retained for 1 to 3 years. Before discarding a document, it is always wise to check with the dentist or other staff members to see if it is still needed.

Nonessential Records

Nonessential records have little importance or only have value for a limited amount of time. Examples include notes about a completed task, meeting reminders, outdated announcements, and pamphlets or flyers that are no longer in use. Common sense dictates when these materials may be discarded.

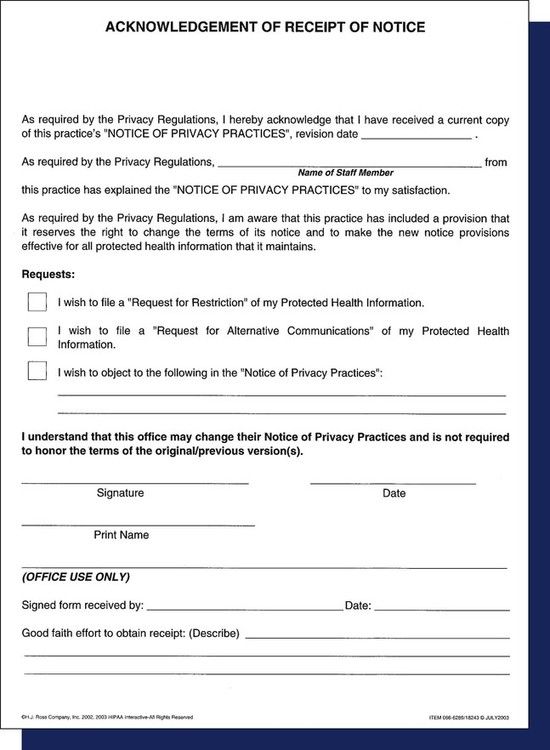

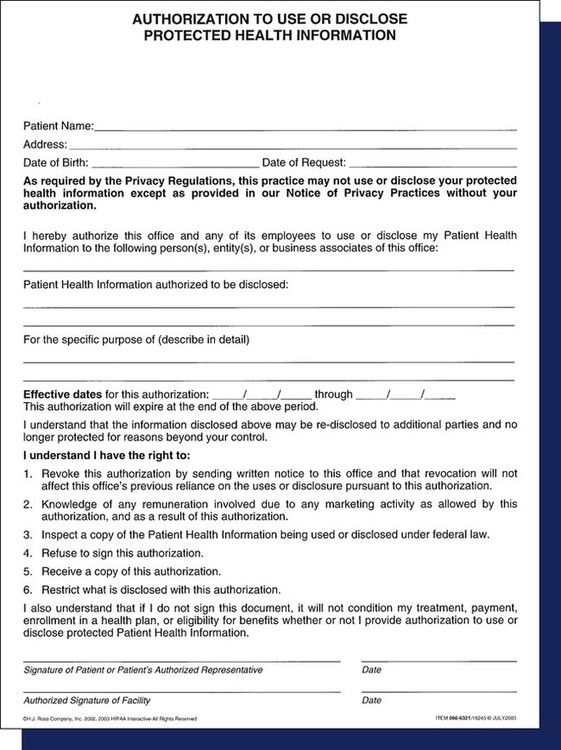

Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act

The Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996 (HIPAA), which became effective in dentistry in April 2003, has affected the business functions of the dental office in a number of ways. HIPAA laws may seem daunting at first; however, their purpose is to protect and enhance patient rights, and everyone is a patient at one time or another.

The HIPAA Privacy and Security Rules mandate federal protection for individually identifiable health information and give patients certain rights with regard to that information. Dental practices that conduct electronic transactions (e.g., claim submission, predetermination, requests for eligibility or benefit information) must comply with the federal requirements. In addition, the dental offices are required to have a business association agreement with any other company or entity with which they electronically exchange this information, such as a benefit carrier or clearinghouse.

HIPAA defines protected health information (PHI) as anything that ties a patient’s name or Social Security number to that person’s health, healthcare, or payment for healthcare, such as radiographs, charts, or invoices. Ensuring the privacy and security of PHI is a legal imperative, but it also protects everyone on the dental team, not just the patient. Overall, the issue of privacy is extremely important for all patient records, both paper and electronic. It is also good risk management, because it helps each dental professional to prevent potential litigation. Each person on the dental team should become familiar with state and federal privacy legislation, because individual states may have additional or more detailed requirements.

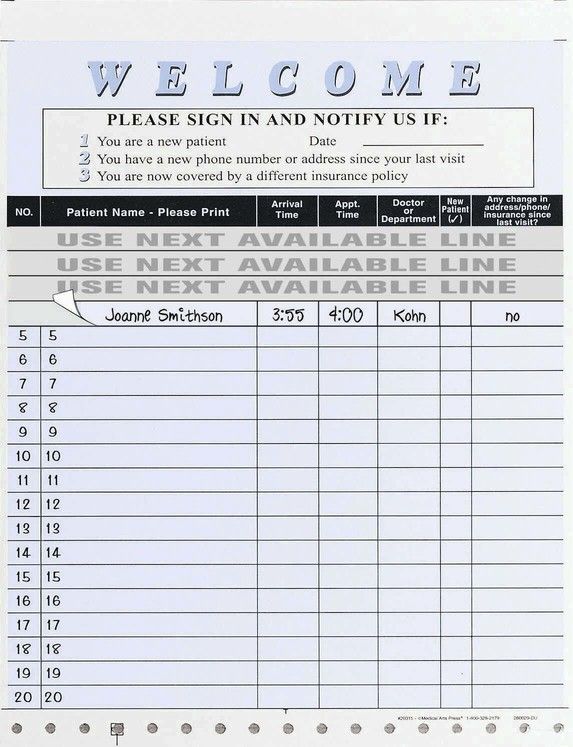

A privacy issue that affects many dental offices is the use of a sign-in sheet for patients to indicate that they have arrived for their appointment. Patient privacy must be protected, so the administrative assistant must make sure that any names on the sheet are not viewable by others. Crossing a name off of a list usually does not obliterate it completely, so tear-off labels such as those shown in Figure 7-2 are commonly used. As soon as the patient signs in, the label can be immediately removed. Other options could include a digital or computerized sign-in process.

The Administrative Simplification provisions of HIPAA require national standards for electronic healthcare transactions. All dentists who transmit or accept patients’ healthcare information electronically must use these standard formats. They must also apply for and use a National Provider Identifier (NPI) in all e-transactions. Dental practices that do not have software or transmission capabilities that are compliant with the standards are able to send their data to a healthcare clearinghouse. The clearinghouse verifies the accuracy of the information, “translates” it into the legally required formats, and then transmits it to the benefit carrier or other target entity. Paper transactions are not subject to HIPAA’s Administrative Simplification Statute and Rules. The most affected area in the dental office is the area of transmission of dental claim forms, which is reviewed in Chapter 14.

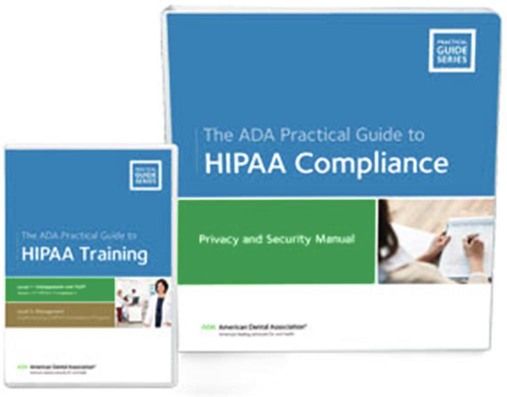

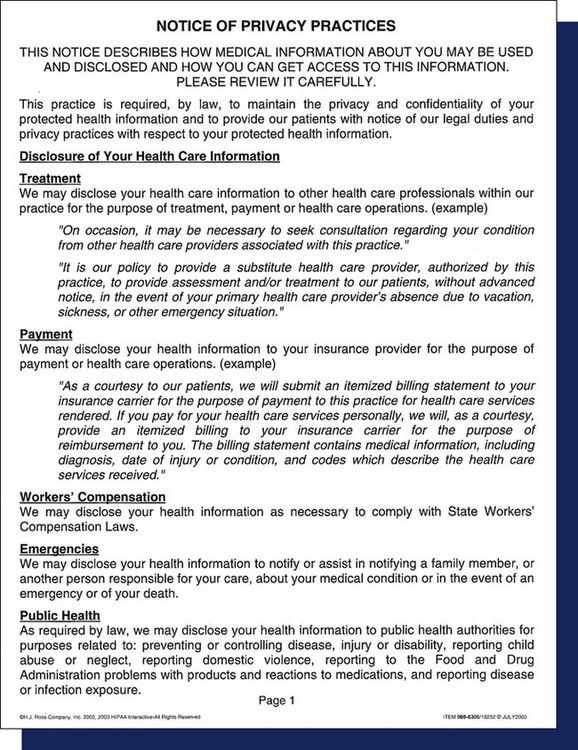

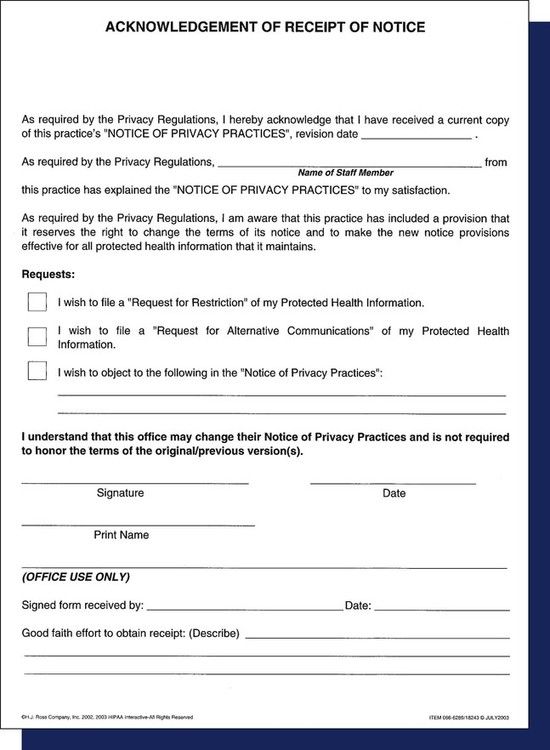

The American Dental Association (ADA) and most state dental associations have done an excellent job of providing members with the necessary tools for the implementation of HIPAA. The ADA and state dental associations as well as many dental office stationers provide a HIPAA Security Tool Kit such as the one shown in Figure 7-3. This kit contains most of the forms needed for privacy practices, including the following:

Box 7-1

HIPAA Privacy Checklist

The purpose of the HIPAA Privacy Rules is to safeguard the privacy of patients’ confidential health information.

*An excellent resource for templates for these items is the American Dental Association’s HIPAA Privacy Kit, available at www.ada.org or from a dental stationery supply house.

Modified from Mary Govoni, CDA, RDA, RDH, MBA, Clinical Dynamics, Okemos, MI (www.marygovoni.com).

Box 7-2

HIPAA Security Checklist

The purpose of the HIPAA Security Rules is to safeguard the confidentiality and integrity of electronic data regarding patients and their protected health information.

*An excellent resource for templates for these items is the American Dental Association’s HIPAA Privacy Kit, available at www.ada.org or from a dental stationery supply house.

Modified from Mary Govoni, CDA, RDA, RDH, MBA, Clinical Dynamics, Okemos, MI (www.marygovoni.com).

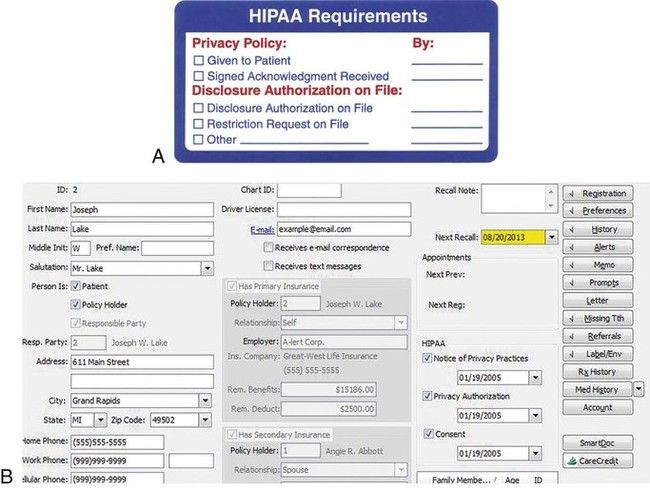

Other forms, such as the Health Information Access-Response/Delay, Complaint, and Staff Review of Policies and Procedures forms, are available in the ADA manual or from the state dental society. To ensure that records are maintained for patients, a preprinted chart label can provide information about important HIPAA information for paper patient files (Figure 7-7, A and B) or notations made in the patient computerized record.

Clinical Records

Patient records generally fall into two categories: clinical and financial. Clinical records are reviewed in this chapter, and financial records are discussed in Chapter 15. A recall system can be considered a type of clinical record, but it is maintained separately; see Chapter 12 for a discussion of this system.

The clinical record is a collection of all of the information about a patient’s dental treatment. In many practices, the clinical record is referred to as the patient’s chart; these terms are often interchangeable. Although each patient’s clinical record is used during dental treatment, updating and maintaining this record is the administrative assistant’s responsibility. The successful maintenance of clinical records requires cooperation and efficiency from each member of the dental office team.

Accurate clinical records are vital for several reasons:

Components of a Clinical Record

A patient’s clinical record commonly includes the following:

Bulkier materials such as diagnostic models are generally stored in an area other than the business office. A cross-reference in the patient record makes these materials easier to locate.

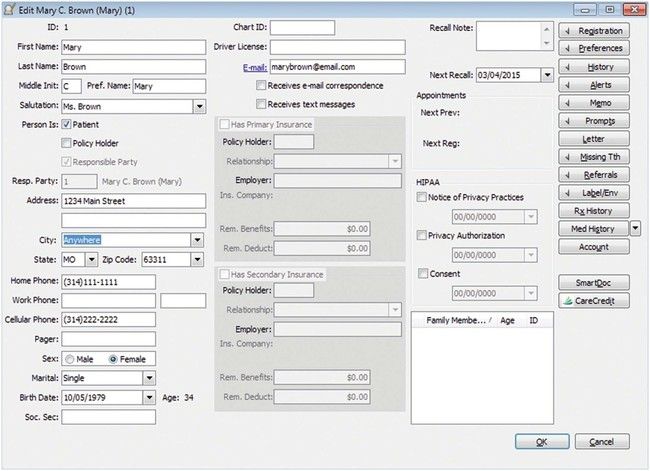

Although the dentist chooses the components and mode of the clinical record, staff members’ input is valuable to ensure that all of the information needed to manage the business systems is collected accurately and efficiently. Most offices use computerized systems for at least part of the administration process, but they may keep paper documents for some data. The practicality and need for paper documents continues to decline as the capability and scope of dental software provide secure, user-friendly functions and storage for all types of clinical records.

Electronic Health Records

Legislation and mandates from the federal government are key drivers of the movement for all healthcare providers to use electronic health records (EHRs) in a universally standardized format. The ultimate goal of the EHR system is to enable the sharing of health information among authorized providers across multiple healthcare settings. Under this system, healthcare providers would be required to use certified healthcare record technology that has been approved by specifically designated federal agencies as using compliant systems, standards, and interfaces that work together to create, manage, store, and share information. Although the terms electronic medical records (EMR) and electronic dental records (EDR) are also used, EHR is generally used to indicate certified technology systems.

Patient File Envelope or Folder for Paper Records

Most dental practices use an  × 11-inch file envelope or folder to contain clinical paper documents. Records of treatment for transient or one-time patients may be kept together in one folder or file location. File envelopes may be plain or color-coded. They are supplied in a preprinted format with spaces for patient information, including the patient’s name, address, and telephone number (Figure 7-8). This type of envelope is widely used, and it satisfies the needs of many practices.

× 11-inch file envelope or folder to contain clinical paper documents. Records of treatment for transient or one-time patients may be kept together in one folder or file location. File envelopes may be plain or color-coded. They are supplied in a preprinted format with spaces for patient information, including the patient’s name, address, and telephone number (Figure 7-8). This type of envelope is widely used, and it satisfies the needs of many practices.

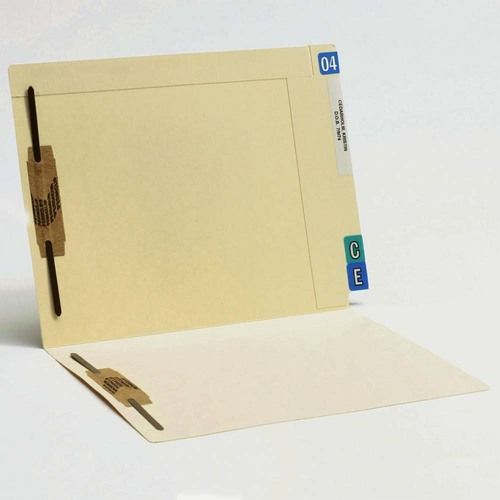

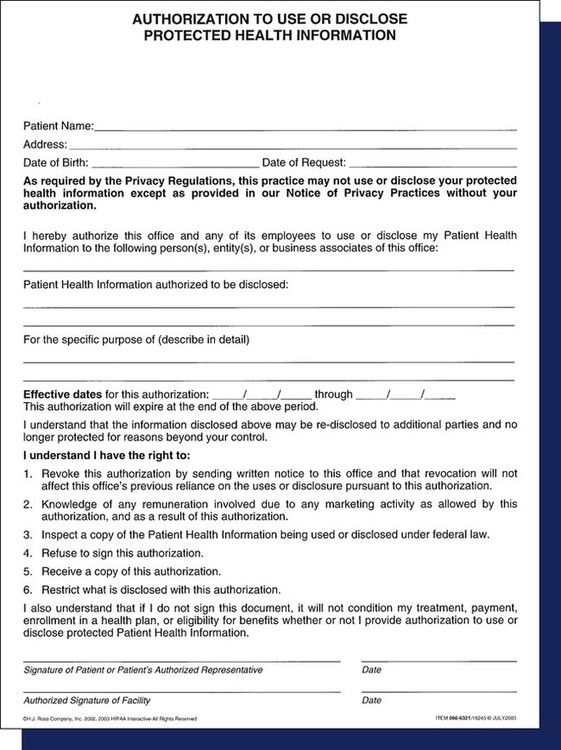

Another very common type of storage for paper records is an end-tab file folder with one or two two-hole fasteners (Figure 7-9). This type of folder requires the use of vertical-style records. The folders generally have a reinforced tab for easy label placement. They are also precut for the quick insertion of a two-hole file fastener. Options include folders with pockets and diagonal cuts, expandable folders, and polyvinyl pockets to hold small materials such as radiographs and CDs.

Whether folders or envelopes are used, some form of color-coding is necessary to make sorting, storing, and retrieval easier. Color-coding can be done as an alphabetical system, or, in a group practice, it can be used to categorize by dentist. In addition to a label with the patient’s name, either an alpha or numeric label system can be used to sort the records. Year aging labels can be used to identify inactive patient records that may need to be purged from the active storage system.

Patient Registration and Health History Forms

Although they are often combined, these two forms contain two different types of data. The information gathered on these forms should be retained in the patient’s paper file or by scanning the completed form into a computer. Generic paper forms are available from dental forms suppliers. Custom forms can be designed by most companies at an additional cost to address the special needs of a specific office. Electronic versions of these forms are also available.

Some forms address privacy issues with questions such as, “May we leave a message on your answering machine at the phone number you have given?” or “May we contact you at a cell phone number or text message you?” Most supply companies provide patient forms in English and Spanish versions for use in various areas of the country. Many offices with Spanish-speaking patients have both versions available.

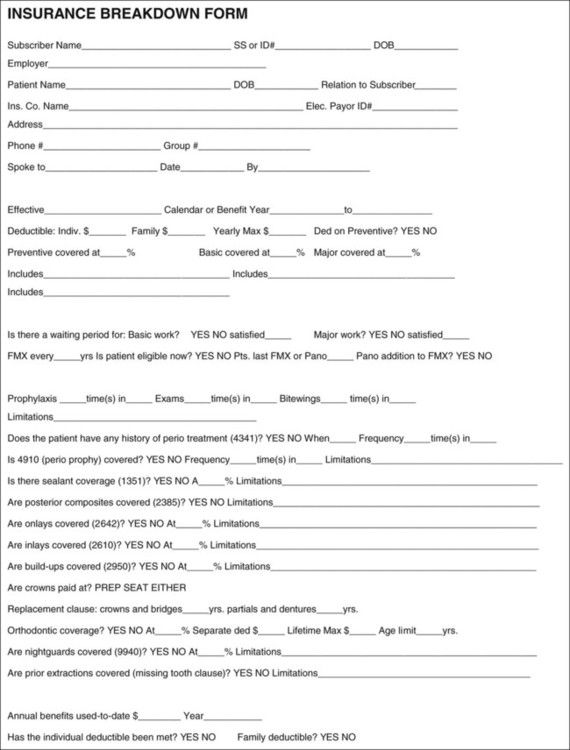

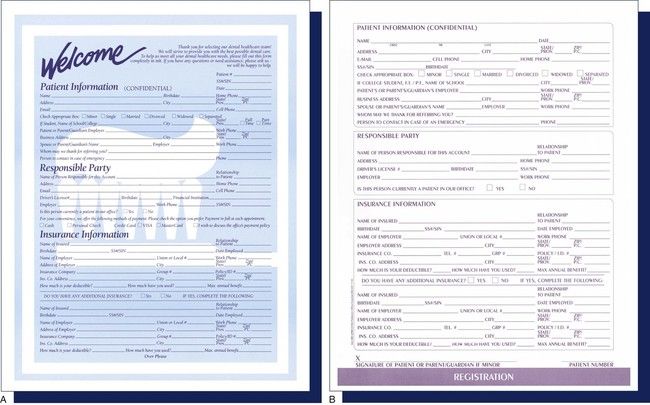

The patient registration form contains general information such as addresses, telephone numbers, and e-mail address as well as employment and insurance information (Figure 7-10). This form enables the staff members to become better acquainted with the patient, and it can provide information for third-party payments and credit checks. Make sure that no nicknames are used and that all data are accurate, because this information is used later to complete insurance forms. Incomplete information on this form can complicate account collection later. In addition, many offices use a breakdown of benefits form to gather and organize detailed benefit coverage from the patient’s insurance carrier (Figure 7-11). Keep patients’ records current by asking if there have been any changes in their personal, work, or insurance information at each visit (Figure 7-12).

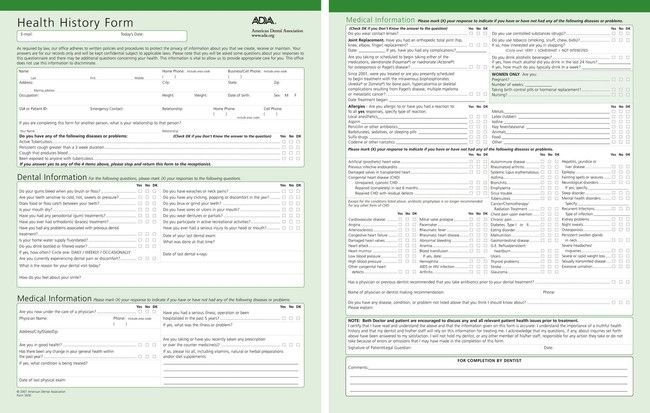

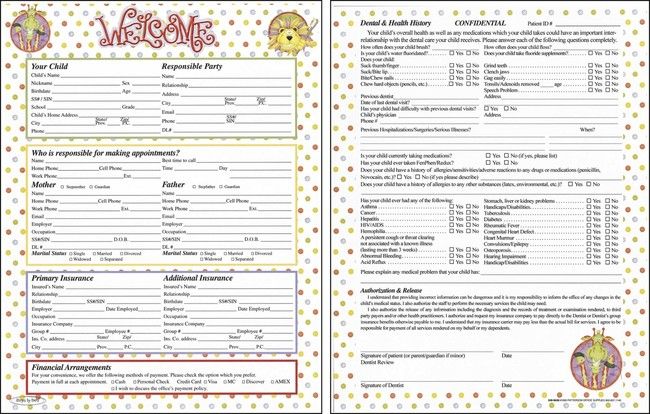

Each patient should fill out a health history form (Figure 7-13) and then date and sign it. If the dentist prefers to ask these questions in person, the patient should verify the answers recorded and then sign the form. The health history form for a child should be completed by a parent or legal guardian, not by the child or a babysitter (Figure 7-14).

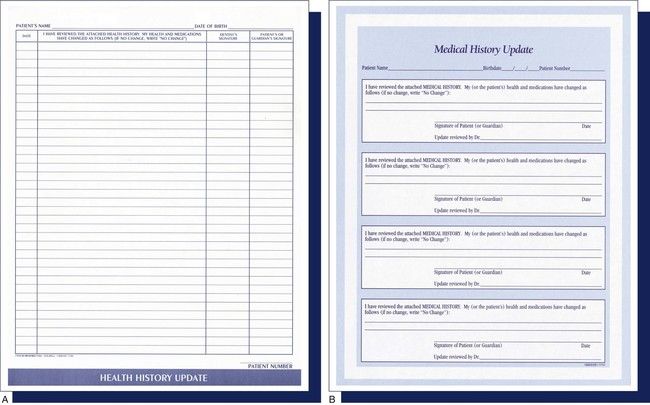

The patient’s history should be reviewed when the person returns for treatment if several months have elapsed since the last visit. Depending on the dental office’s policy and the length of time since the patient was seen, the administrative assistant may have the patient fill out a complete health history form or a shorter health history update form (Figure 7-15). The patient should sign and date this form.

Many types of patient registration and health history forms are available in print and electronic formats. The forms can be filled out by the patient when he or she presents for an appointment; they can be mailed or e-mailed so that the patient can complete the forms and bring them in; or they can be posted to the dental office’s website and filled out online. Regardless of the format used, it is important to remember that a current and accurate health history serves as a preventive measure during patient treatment and as a defense in malpractice suits.

When a patient is filling out the forms in the office, certain conditions need to be present:

A person’s privacy is protected by law, and questions that may be considered discriminatory or in violation of a patient’s rights must be avoided. Consequently, the administrative assistant must be aware of the state laws that protect a person’s rights and recommend changes to the form that accommodate these rights. Local and state dental associations monitor legislation that affects dentists and keep members informed. As legal changes occur, most suppliers update their forms for compliance.

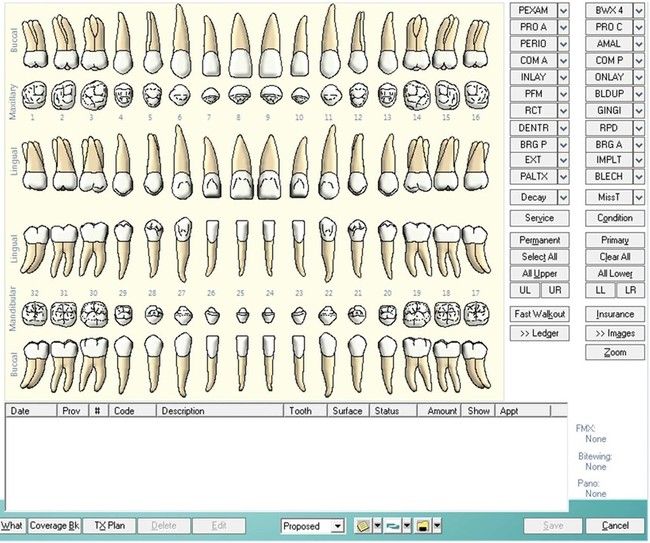

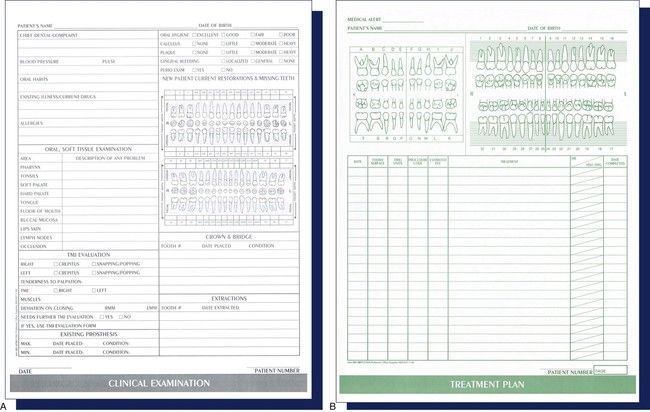

Clinical Chart

A wide selection of dental charts is available for both general and specialty practices, but both electronic and paper formats have several basic points in common: patient identification (name, date of birth), a tooth chart diagram (permanent, deciduous, or a combination of both), and an area for clinical notes. Clinical notes may include general oral condition, the state of the gingival tissue, temporomandibular joint issues, and the dates of the placement of fixed or removable prosthetics. Most supply companies offer a special service for dentists who want to design their own paper charts; however, the customization of software products is generally unavailable or cost prohibitive.

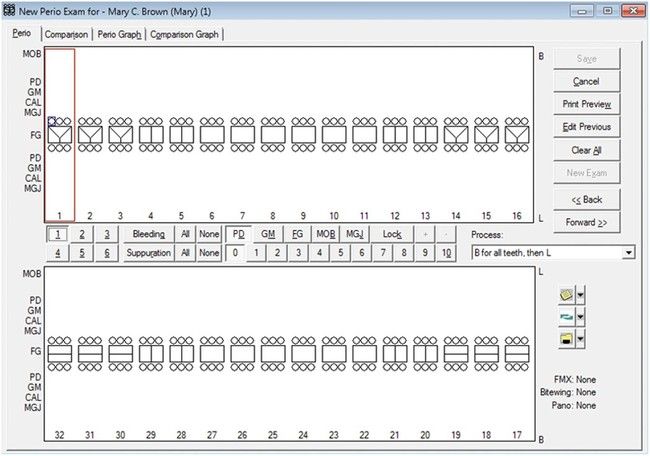

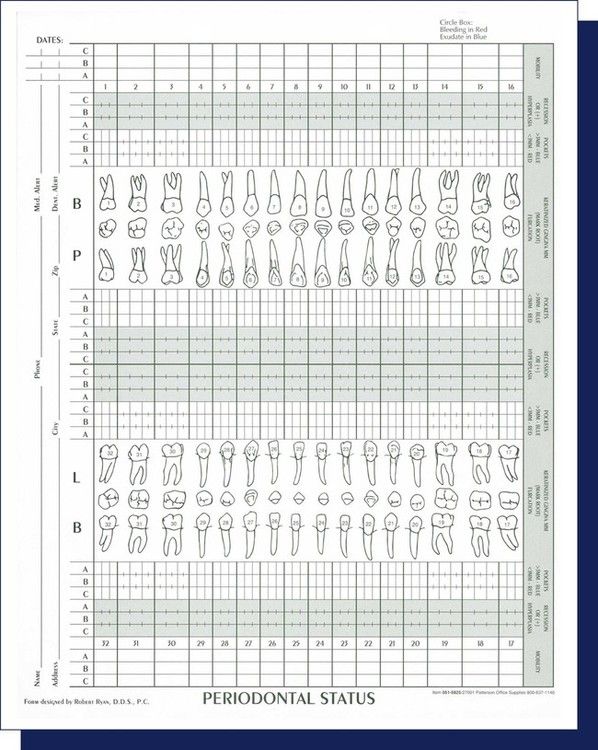

Most paper charts are  × 11 inches in size, made of heavy paper stock, and printed on both sides (Figure 7-16). One side of the record contains a tooth chart, an overview of the patient’s health history, and general oral information or clinical notes. Some forms are designed to allow for the recording of periodontal measurements on the tooth chart, or the dentist or hygienist may use a separate form for periodontal charting (Figure 7-17).

× 11 inches in size, made of heavy paper stock, and printed on both sides (Figure 7-16). One side of the record contains a tooth chart, an overview of the patient’s health history, and general oral information or clinical notes. Some forms are designed to allow for the recording of periodontal measurements on the tooth chart, or the dentist or hygienist may use a separate form for periodontal charting (Figure 7-17).

The layout and design of clinical records may vary in different software systems, but these generally include the same information as the paper chart, which often involves a feature for recording periodontal measurements (Figure 7-18).

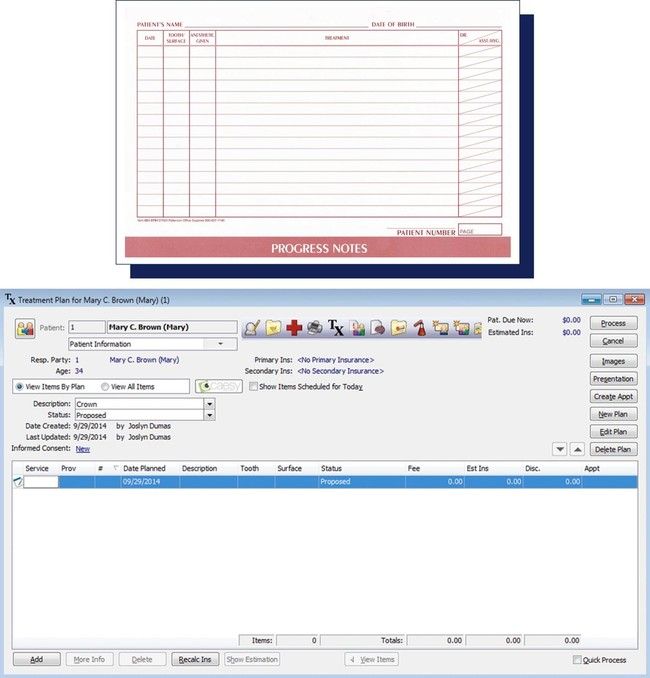

Treatment Record/Progress Notes

The reverse side of the paper clinical chart or a separate treatment sheet may be used for entering the services rendered and the associated fees. Progress notes can be included here or documented on a different sheet. Computer software systems generally have modules for entering services and fees and for recording notes. The administrative assistant enters the date, services, and fees into the patient’s financial record where payments and balances are maintained.

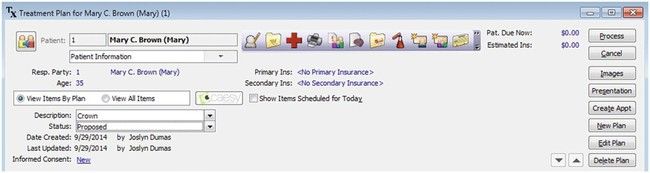

Dental Diagnosis, Treatment Plan, and Estimate

This form includes the dentist’s diagnosis and the treatment plan recommended for the patient (Figure 7-19). In many cases, the patient can select options in the treatment plan. After the consultation has been completed and treatment has been accepted by the patient, the form may be signed by the person responsible for the account. Often a clause is included to explain that the fee quoted is an estimate and that unforeseen circumstances may affect the final fee for the service.

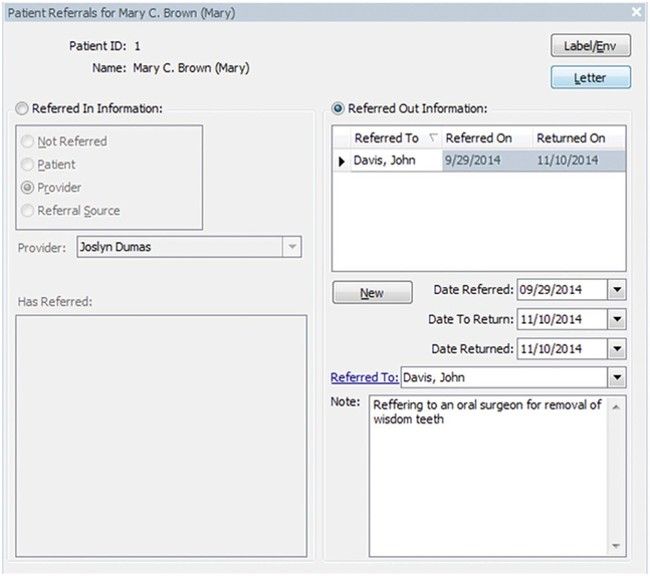

Consultation and Referral Report

In some cases, the dentist refers a patient to another dentist for examination, evaluation, and diagnosis. The form shown in Figure 7-20 includes information about the patient, the reason for the referral, and an anticipated treatment plan. This form is sent to the referring dentist, with a copy being sent to the patient as well. The consultant enters an evaluation and recommendation on the form and returns it to the dentist.

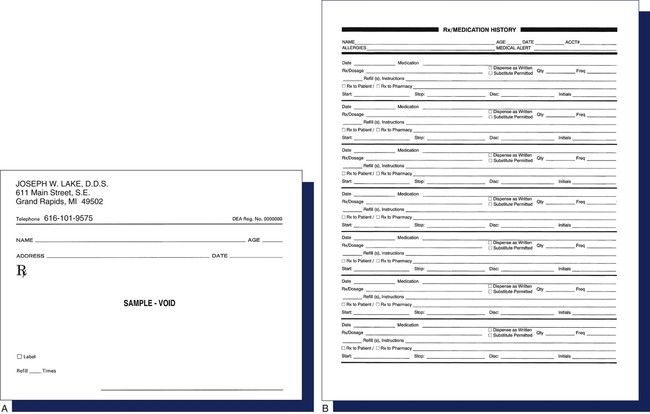

Medication History and Prescriptions

Having a history and current list of all medications taken by a patient helps to prevent the prescription of drugs that could lead to unsafe interactions or that may negatively affect a chronic health condition. As in a medical practice, medications are prescribed for a dental patient on a paper prescription form (Figure 7-21, A and B) or through a qualified electronic prescribing system. E-prescription systems must be certified EHR technology; these can be stand-alone modules or part of a complete EHR system. With e-prescribing, dentists can route prescriptions electronically to the patient’s preferred pharmacy in addition to reviewing the patient’s medication history and insurance information. Some states require specific formats for prescription forms, and virtually all states authorize e-prescribing for the majority of prescription drugs (noncontrolled substances). If a patient elects to use a mail-order prescription service, prescriptions can usually be submitted on paper, via fax, or through an electronic portal.

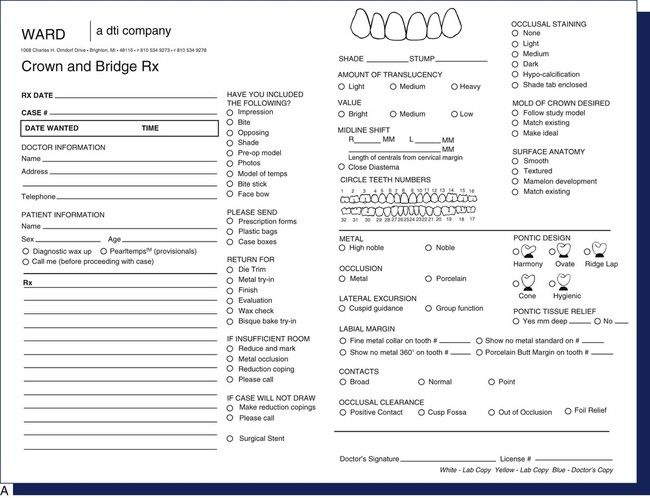

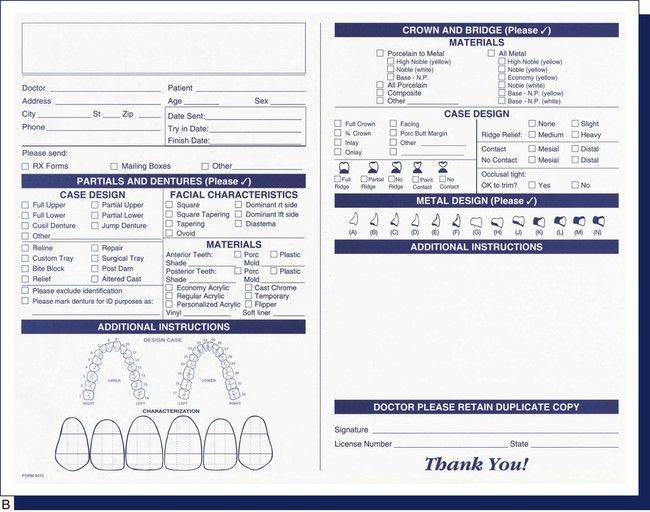

Laboratory Requisitions

Many states require that a prescription or laboratory requisition form (Figure 7-22) accompany each case that a dentist sends to a dental laboratory. This blueprint improves communication between the dentist and the laboratory technician and helps eliminate illegal dental practices, thereby protecting the patient.

Consent Form

A consent form is commonly used in dentistry as a preventive measure against malpractice suits. The form, which is signed by the patient or by the parent or legal guardian of a pediatric patient, grants permission for the administration of anesthetic and other specified procedures. It is impossible to have a consent form for every phase of treatment, and it is unrealistic to believe that a general consent form that covers every possible procedure would be upheld in court. Therefore, a written summary of the treatment plan as agreed upon by the patient and dentist and that is dated and signed by both parties is a more acceptable format for such consent. Chapter 4 reviews the use of various types of consent forms in the dental office (see Figure 4-2).

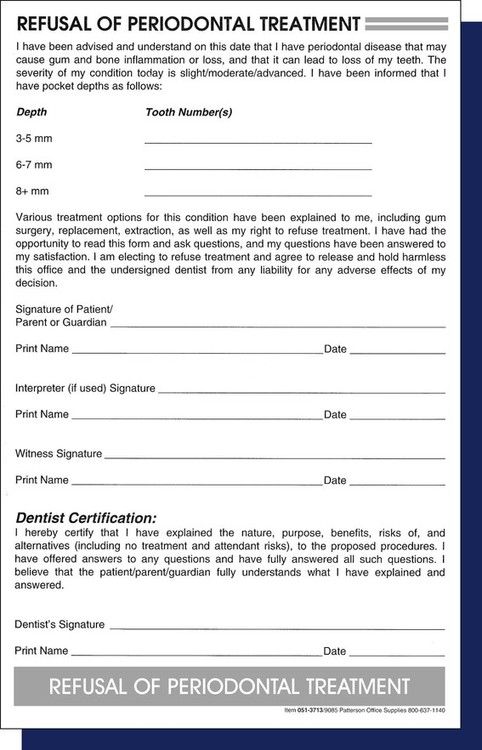

Refusal of Treatment

There may be a time in the dental practice when a patient refuses to undergo recommended treatment for a condition that presents potential risks. To ensure that litigation does not ensue, the dentist should have the patient sign a refusal of treatment form (Figure 7-23) that includes the nature of the treatment, alternative treatments, treatment risks, and risks if no treatment is rendered.

Radiographic Films

A patient’s radiographic films should be labeled with the patient’s full name, the date of the exposure, the number and type of films, and the dentist’s name. If radiographs are copied and mailed or transmitted to another practitioner, the name and date of transfer should be noted in the clinical chart. In addition, a signed release request from the patient must be retained in the patient’s record.

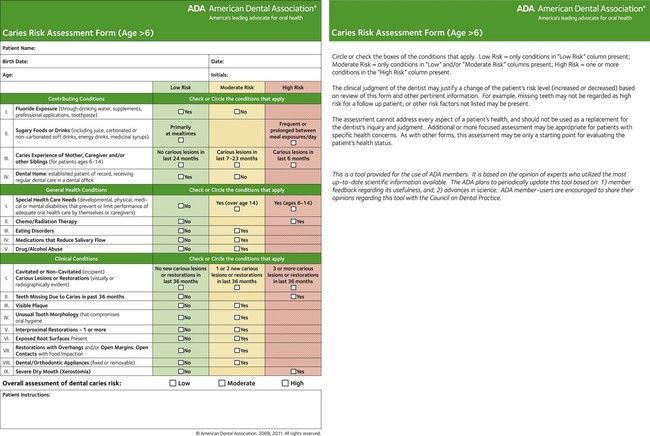

Test Results

Dated copies of test results are kept in the patient’s clinical record. These could include allergy testing and caries or periodontal risk evaluations (Figure 7-24).

Entering Data on a Clinical Chart

Several types of data are entered in the various components of a patient’s record, including the charting of existing conditions, which is done with a variety of symbols and codes; the recording of treatment procedures and codes; treatment plans; and discussions with the patient about recommended treatment. Medical warnings are also noted and can be called out with warning flags as shown in Figure 7-25. Some paper clinical charts provide space on the back of the form for handwritten notes, or they may be entered by the dentist or the assistant into a computer terminal or tablet. All data entered in a patient’s clinical chart as well as progress notes should be dated, accurate, comprehensive, and initialed or digitally verified by the treating dentist, hygienist, and assistant (Figure 7-26). One of the major concerns during legal proceedings is incomplete data on a patient record. All interactions (including nonactions, such a patient declining or delaying treatment) should be recorded in the clinical record. Failure to document any activity completely and accurately may prove costly in a lawsuit. Box 7-3 lists several rules for entering data, beginning with the creation of the record.

Box 7-3 Rules for Entering Data in a Clinical Record

Types of Clinical Data Entries

Entering information on the patient’s clinical chart or progress notes involves the use of tooth-numbering systems, abbreviations, and symbols. The administrative assistant must understand each of these systems as well as the basic descriptions of the oral cavity. For example, there are two arches: the maxilla or maxillary arch (upper jaw) and the mandible or mandibular arch (lower jaw). There are four quadrants: maxillary right and left and mandibular right and left. There are six segments: the maxillary and mandibular right and left posterior segments, which include the molars and the premolars (bicuspids), and the two anterior segments, which include all anterior teeth on the right and left in both arches, from canine (cuspid) to canine (cuspid).

Practice Note

Practice Note

The failure to document any activity completely and accurately may prove costly in a lawsuit.

Tooth Nomenclature

The administrative assistant should be able to identify the names and numbers of the teeth in both the primary and permanent dentition (see Box 7-4). Mixed dentition (a combination of primary and permanent teeth) usually exists from approximately 6 to 12 years of age. For example, a child may have lost the primary central incisors, and the first permanent molars may have erupted; however, the primary first and second molars are still firmly in place. Mixed dentition occasionally occurs in an adult when a primary tooth is retained as a result of a missing or misaligned permanent tooth.

Box 7-4 Primary and Permanent Dentition

Teeth present a good appearance and provide support for other structures. They also aid in swallowing, mastication, digestion, and the production of speech and phonetics. The primary dentition creates the framework for the eruption of a healthy permanent dentition. Premature loss of the primary teeth can be directly related to future dental disease or other dental anomalies. Likewise, the loss of a single permanent tooth can be the start of serious dental impairment if it is not replaced. The administrative assistant plays an important role in patient education. He or she is responsible for teaching patients about how to retain healthy teeth and a healthy mouth for a lifetime. To be an effective team member, the administrative assistant must understand and be able to communicate to patients the reasons for maintaining dental health and why this is intrinsic to good overall health.

A qualified clinical assistant understands the correct identification of a tooth in the oral cavity and the sequence of terms used to identify it. Confusion in the order of identification can cause many communication problems and administrative issues. The correct sequence of identification most commonly used is as follows: the dentition, the arch, the quadrant, and the specific tooth (see Box 7-5). For example, when describing a patient’s complaint, the problem tooth should be defined as the permanent maxillary right first molar.

Box 7-5 Categories of Tooth Identification

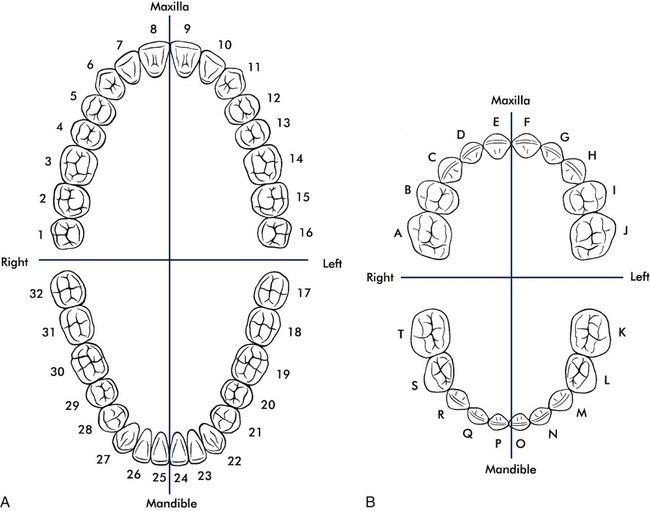

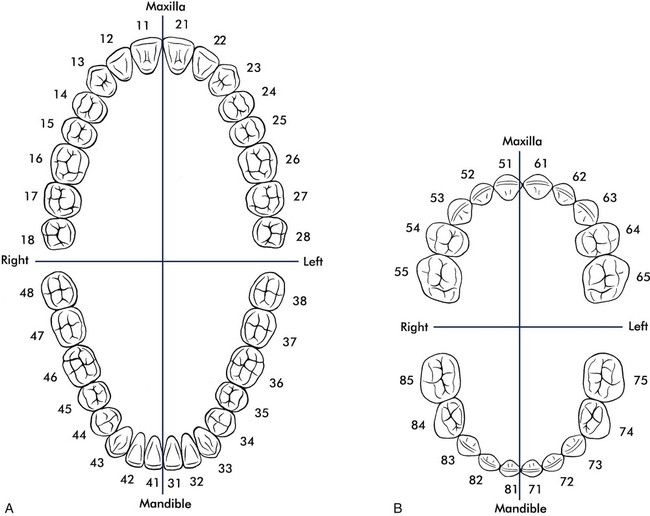

Tooth-Numbering Systems

Every dental office makes use of a specific numbering system to chart the patient’s oral cavity or to refer to dental treatment to be performed. There are several numbering systems, and the dentist and staff choose which one is used in the office. The objective of a numbering system is to identify each tooth numerically or alphabetically. This number or letter provides an abbreviated form of tooth reference, and it helps with consistent records management. The three most common numbering systems are the Universal Numbering System, the Palmer Notation System, and the Fédération Dentaire Internationale (FDI) system.

Universal/National Numbering System.

The most popular numbering system is the universal/national numbering system. It uses the Arabic numerals from 1 through 32 for the permanent dentition and the letters A through T for the primary dentition.

The universal system begins numbering the permanent teeth with the most posterior tooth in the maxillary right quadrant; this is the third molar, and it is assigned as tooth #1. Numbering for the primary dentition begins with #A for the primary maxillary right second molar. The numbering continues toward the anterior midline to the right central incisor, which is tooth #8 of the permanent dentition and tooth #E of the primary dentition. The numbering continues to the maxillary left quadrant, from the midline to the most posterior tooth, which is #16 of the permanent dentition and #J of the primary dentition. The numbering drops to the mandibular left quadrant to permanent tooth #17 or primary tooth #K and then across the arch to the mandibular right most posterior tooth, tooth #32 or #T (Figure 7-27).

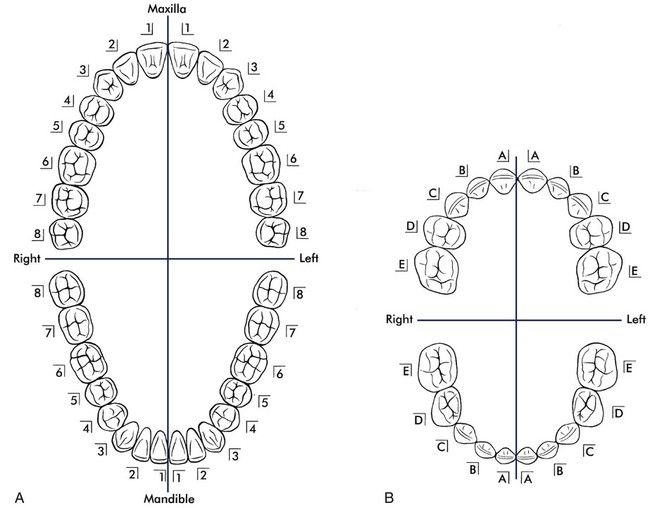

Palmer Notation System.

The Palmer notation system assigns each of the four quadrants a bracket to designate the area of the mouth in which the tooth is found. In Figure 7-28, A, the left side of the chart represents the patient’s right side, and the right side of the chart represents the patient’s left side. It might be depicted as follows:

| Maxillary right | Maxillary left |

| Mandibular right | Mandibular left |

Each permanent tooth in the individual quadrants is assigned a number from 1 through 8, with #1 beginning at the midline and increasing to #8 distally. This may be written as follows:

The direction of the bracket indicates the arch, and the number within the bracket indicates the tooth, as follows:

For the primary dentition, brackets are used to assign a quadrant, but the teeth are designated by the letters A through E. A specifies the central incisors, and E specifies the second molars (Figure 7-28, B).

International Standards Organizational System/ Fédération Dentaire Internationale System.

To create a numbering system that could be used internationally as well as by electronic data transfer, the World Health Organization accepted the International Standards Organization (ISO) System for teeth. In 1996, the ADA accepted the ISO system, in addition to the Universal/National System. The ISO system is based on the Fédération Dentaire Internationale (FDI) System and is used in many countries.

The ISO/FDI system (Figure 7-29) assigns a two-digit number to each tooth in each quadrant. The first number indicates the quadrant in which the tooth is positioned, and the second number identifies the specific tooth. The numbers 1 through 4 are assigned to the quadrants of the permanent dentition, and the numbers 5 through 8 are assigned to the quadrants of the primary dentition.

| Number | Quadrant |

| 1 | Permanent maxillary right |

| 2 | Permanent maxillary left |

| 3 | Permanent mandibular left |

| 4 | Permanent mandibular right |

| 5 | Primary maxillary right |

| 6 | Primary maxillary left |

| 7 | Primary mandibular left |

| 8 | Primary mandibular right |

The second number identifies the specific tooth in the arch. The numbers 1 through 8 are assigned to the permanent dentition and 1 through 5 to the primary dentition, starting at the midline and moving posteriorly. Tooth #1 in all arches indicates a central incisor, and then the numbering proceeds to the last tooth in the quadrant. The two assigned numbers are read separately, with the first digit signifying the quadrant and the second digit identifying the tooth. Some examples are as follows:

The primary dentition is handled in the same manner. However, because there are only five teeth per quadrant, the numbers would range from 1 through 5 for each tooth and 5 through 8 for the quadrants. Therefore, the primary maxillary right first molar is #54 (number five-four), and the primary mandibular left lateral incisor is #72 (number seven-two).

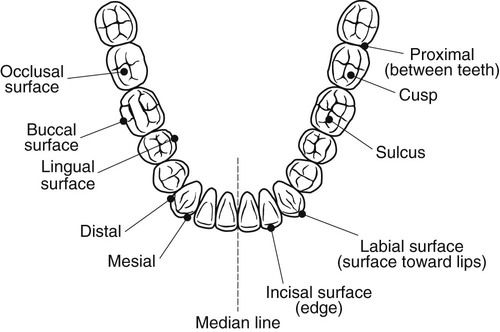

Tooth Surfaces

During routine charting procedures, the clinical assistant uses a set of alpha codes for tooth surface annotation. The use of tooth nomenclature and surface annotation makes it easy to identify an area of a specific tooth in which there may be dental decay, a fracture, or a restoration. The administrative assistant must be familiar with this terminology to complete insurance forms and to consult with other staff about patient treatment.

All crowns of the teeth are divided into surfaces, which are identified by their position in relation to the oral cavity. For example, the surfaces nearest the lips are referred to as the labial or facial surfaces. The posterior teeth (the premolars and molars) have five surfaces. The anterior teeth (the incisors and canines) have four surfaces plus a ridge. Both anterior and posterior teeth have four axial surfaces. The axial surface runs vertically from the biting surface to the apex of a tooth. The posterior teeth have one additional surface, the occlusal surface, which is the horizontal surface that runs perpendicular to the other axial surfaces.

The surfaces of the teeth not only have names, but they are also identified by letters or numbers. This surface annotation is used to simplify charting notations and for all insurance reports. The letter or number is commonly placed as a superscript (above the print line) next to the tooth number. For example, when using the universal numbering system to describe a procedure involving the mesial surface of the permanent maxillary left first molar, the assistant would write “#14M” or “#141.” The surfaces of the teeth are indicated as follows (Figure 7-30):

The proximal areas or surfaces are where two teeth abut or face each other. Most teeth have two proximal surfaces: the mesial and the distal proximal surfaces; however, for the third molars, only the mesial surface may be considered a proximal surface. Interproximal denotes the area between two proximal teeth. For example, a carious lesion on the proximal surface is called interproximal decay.

When more than one surface is involved (e.g., mesial, occlusal, and distal), the surface annotations are placed in order from mesial to distal: for example, “#19MOD” rather than “#19DOM” or “#19ODM.” This standardization provides for uniform communication among dental professionals.

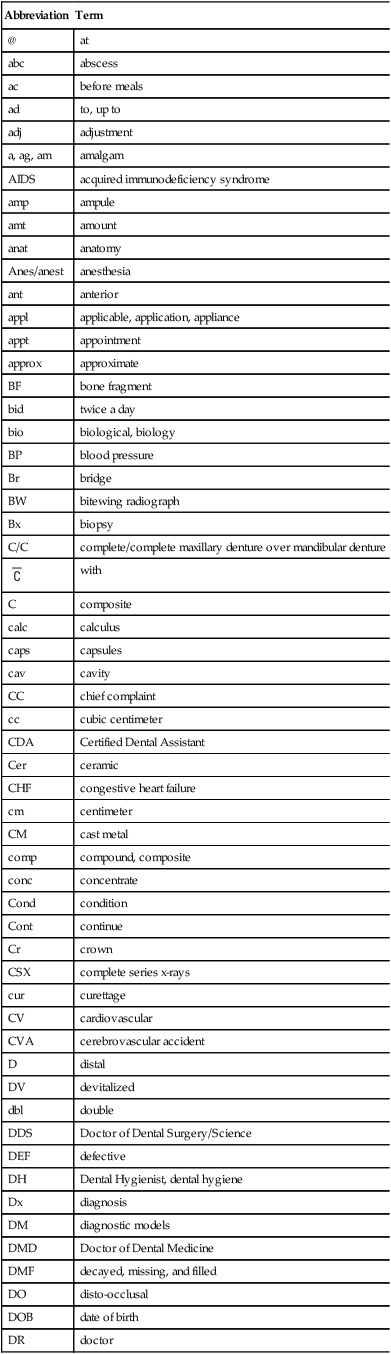

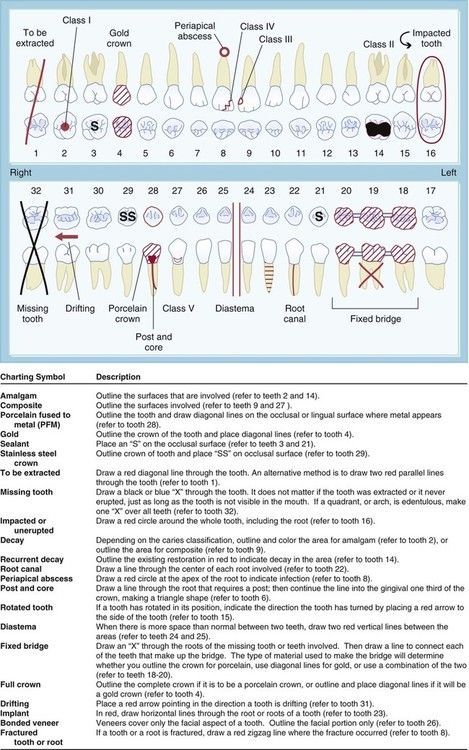

Charting Symbols and Abbreviations

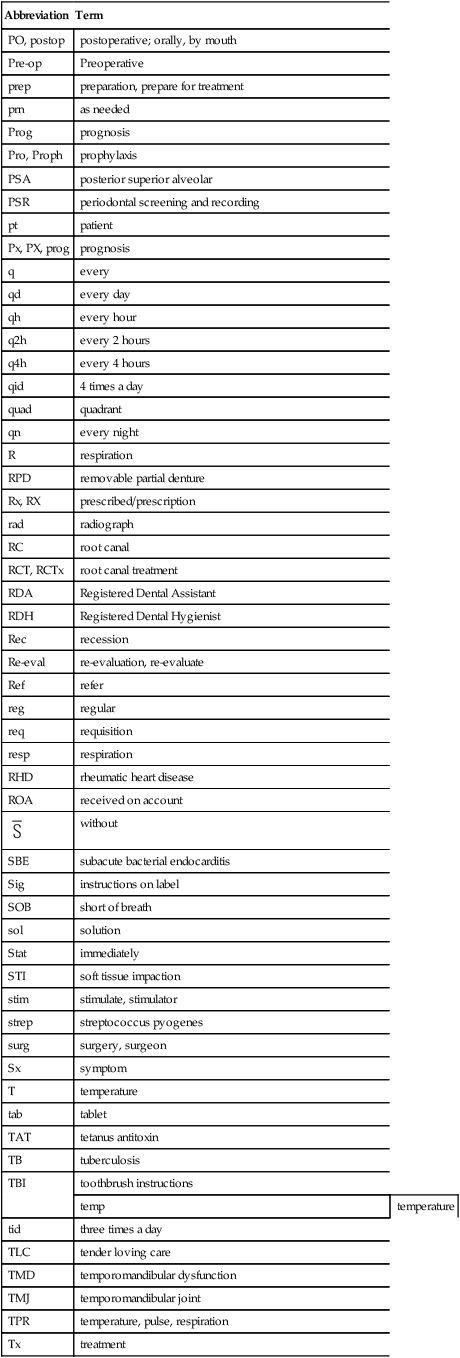

Charting symbols are a form of shorthand used in the dental office to create a visual representation on a paper or electronic anatomical diagram that shows conditions in and around the patient’s teeth (Figure 7-31). The dentist can use this information for diagnosis and treatment planning, or the administrative assistant can quickly identify conditions in the patient’s mouth without reading through a lengthy description. Figure 7-32 presents a variety of symbols that are commonly used in a dental office. Clinical abbreviations are short versions of or initials for common clinical terminology. Table 7-1 contains a detailed list of commonly used abbreviations.

Records Retention

The minimum retention period for a patient’s record should be consistent with the statute of limitations within the state. The statute of limitations, which is the period within which a civil suit for alleged wrongdoing may be legally filed, varies from state to state. The average minimum amount of time for the retention of a patient’s records is approximately 6 years after the performance of the last treatment, but the dentist may decide to retain some or all records longer than that. Chapter 8 offers suggestions for longer-term storage.

Records Transfer

Requests for the transfer of records are made for many reasons, including the following: (1) the patient wants to change dentists; (2) the patient is moving out of the area; (3) the dentist wants to consult with another dentist; and (4) the patient has been referred to another dentist.

Care must be taken when completing a request for the transfer of a patient’s records. By law, any information regarding a patient’s care and treatment is confidential and privileged. This privilege belongs to the patient, not to the dentist. Therefore, for the dentist’s protection, it is prudent to obtain a written consent signed by the patient or the patient’s legal representative before transferring records to anyone other than the patient. The patient’s right to privacy may only be superseded by a legal action or court order directing the dentist to release specific records to a designated party, such as a lawyer, judge, or other legal representative. In general, if the following suggestions are followed, record transfer can be handled efficiently and confidentially.

Practice Note

Practice Note

By law, any information about a patient’s care and treatment is confidential and privileged.

The dental office’s responsibilities include the following:

Occupational Safety and Health Administration Records

Chapter 17 details the responsibilities of the administrative assistant for disease prevention. Specific records must be maintained for the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA). The Regulatory Compliance Manual (see Figure 17-2, B) developed by the ADA is an important source of samples and suggestions for developing the documents required by federal regulations.

Employee Records

Several employee records must be maintained in the office. These must be accurate, and they must be maintained with strict confidentiality. The administrative assistant is responsible for periodically updating these records. Many of the records relate to payroll, and these are discussed in Chapter 16.

Employee records are classified into various categories, such as the following:

Employment Tax Information Forms (see Chapter 16)

Learning Activities

Please refer to the student workbook for additional learning activities.

Please refer to the student workbook for additional learning activities.

FIGURE 7-1 Life cycle of a record.

Practice Note

Practice Note

Records have a life cycle that begins with creation and ends with disposition.

Categories of Records

The administrative assistant must be able to decide which records to keep, how to organize and store them, how long they legally must be retained, and when to dispose of them. In general, records can be categorized as vital, important, useful, or nonessential and as active or inactive.

Vital Records

Vital records are essential documents that cannot be replaced. These include patients’ clinical and financial records and the office’s corporate charter and deed, mortgage, or bill of sale. These records should be kept in a fireproof, theft-proof cabinet or safe, and copies of financial records and legal papers are often kept in a protected offsite location.

Practice Note

Practice Note

Vital records are essential documents that cannot be replaced.

Important Records

Important records are extremely valuable to the operation of the office, but they are not vital. They include accounts payable and receivable, invoices, canceled checks, inventory and payroll records, and other federal regulatory records. Such records may be needed for a tax audit or if a question arises about a financial transaction. Important records generally should be retained for 5 to 7 years. Most offices keep them for about 7 years or in accordance with federal or state regulations.

Useful Records

Useful records include employment applications, expired insurance policies, petty cash vouchers, bank reconciliations, and general correspondence. This category is difficult to define, because one office may consider a document useful, whereas another might find it indispensable. These records are usually retained for 1 to 3 years. Before discarding a document, it is always wise to check with the dentist or other staff members to see if it is still needed.

Nonessential Records

Nonessential records have little importance or only have value for a limited amount of time. Examples include notes about a completed task, meeting reminders, outdated announcements, and pamphlets or flyers that are no longer in use. Common sense dictates when these materials may be discarded.

Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act

The Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996 (HIPAA), which became effective in dentistry in April 2003, has affected the business functions of the dental office in a number of ways. HIPAA laws may seem daunting at first; however, their purpose is to protect and enhance patient rights, and everyone is a patient at one time or another.

The HIPAA Privacy and Security Rules mandate federal protection for individually identifiable health information and give patients certain rights with regard to that information. Dental practices that conduct electronic transactions (e.g., claim submission, predetermination, requests for eligibility or benefit information) must comply with the federal requirements. In addition, the dental offices are required to have a business association agreement with any other company or entity with which they electronically exchange this information, such as a benefit carrier or clearinghouse.

HIPAA defines protected health information (PHI) as anything that ties a patient’s name or Social Security number to that person’s health, healthcare, or payment for healthcare, such as radiographs, charts, or invoices. Ensuring the privacy and security of PHI is a legal imperative, but it also protects everyone on the dental team, not just the patient. Overall, the issue of privacy is extremely important for all patient records, both paper and electronic. It is also good risk management, because it helps each dental professional to prevent potential litigation. Each person on the dental team should become familiar with state and federal privacy legislation, because individual states may have additional or more detailed requirements.

A privacy issue that affects many dental offices is the use of a sign-in sheet for patients to indicate that they have arrived for their appointment. Patient privacy must be protected, so the administrative assistant must make sure that any names on the sheet are not viewable by others. Crossing a name off of a list usually does not obliterate it completely, so tear-off labels such as those shown in Figure 7-2 are commonly used. As soon as the patient signs in, the label can be immediately removed. Other options could include a digital or computerized sign-in process.

The Administrative Simplification provisions of HIPAA require national standards for electronic healthcare transactions. All dentists who transmit or accept patients’ healthcare information electronically must use these standard formats. They must also apply for and use a National Provider Identifier (NPI) in all e-transactions. Dental practices that do not have software or transmission capabilities that are compliant with the standards are able to send their data to a healthcare clearinghouse. The clearinghouse verifies the accuracy of the information, “translates” it into the legally required formats, and then transmits it to the benefit carrier or other target entity. Paper transactions are not subject to HIPAA’s Administrative Simplification Statute and Rules. The most affected area in the dental office is the area of transmission of dental claim forms, which is reviewed in Chapter 14.

The American Dental Association (ADA) and most state dental associations have done an excellent job of providing members with the necessary tools for the implementation of HIPAA. The ADA and state dental associations as well as many dental office stationers provide a HIPAA Security Tool Kit such as the one shown in Figure 7-3. This kit contains most of the forms needed for privacy practices, including the following:

Box 7-1

HIPAA Privacy Checklist

The purpose of the HIPAA Privacy Rules is to safeguard the privacy of patients’ confidential health information.

*An excellent resource for templates for these items is the American Dental Association’s HIPAA Privacy Kit, available at www.ada.org or from a dental stationery supply house.

Modified from Mary Govoni, CDA, RDA, RDH, MBA, Clinical Dynamics, Okemos, MI (www.marygovoni.com).

Box 7-2

HIPAA Security Checklist

The purpose of the HIPAA Security Rules is to safeguard the confidentiality and integrity of electronic data regarding patients and their protected health information.

*An excellent resource for templates for these items is the American Dental Association’s HIPAA Privacy Kit, available at www.ada.org or from a dental stationery supply house.

Modified from Mary Govoni, CDA, RDA, RDH, MBA, Clinical Dynamics, Okemos, MI (www.marygovoni.com).

Other forms, such as the Health Information Access-Response/Delay, Complaint, and Staff Review of Policies and Procedures forms, are available in the ADA manual or from the state dental society. To ensure that records are maintained for patients, a preprinted chart label can provide information about important HIPAA information for paper patient files (Figure 7-7, A and B) or notations made in the patient computerized record.

Clinical Records

Patient records generally fall into two categories: clinical and financial. Clinical records are reviewed in this chapter, and financial records are discussed in Chapter 15. A recall system can be considered a type of clinical record, but it is maintained separately; see Chapter 12 for a discussion of this system.

The clinical record is a collection of all of the information about a patient’s dental treatment. In many practices, the clinical record is referred to as the patient’s chart; these terms are often interchangeable. Although each patient’s clinical record is used during dental treatment, updating and maintaining this record is the administrative assistant’s responsibility. The successful maintenance of clinical records requires cooperation and efficiency from each member of the dental office team.

Accurate clinical records are vital for several reasons:

Components of a Clinical Record

A patient’s clinical record commonly includes the following:

Bulkier materials such as diagnostic models are generally stored in an area other than the business office. A cross-reference in the patient record makes these materials easier to locate.

Although the dentist chooses the components and mode of the clinical record, staff members’ input is valuable to ensure that all of the information needed to manage the business systems is collected accurately and efficiently. Most offices use computerized systems for at least part of the administration process, but they may keep paper documents for some data. The practicality and need for paper documents continues to decline as the capability and scope of dental software provide secure, user-friendly functions and storage for all types of clinical records.

Electronic Health Records

Legislation and mandates from the federal government are key drivers of the movement for all healthcare providers to use electronic health records (EHRs) in a universally standardized format. The ultimate goal of the EHR system is to enable the sharing of health information among authorized providers across multiple healthcare settings. Under this system, healthcare providers would be required to use certified healthcare record technology that has been approved by specifically designated federal agencies as using compliant systems, standards, and interfaces that work together to create, manage, store, and share information. Although the terms electronic medical records (EMR) and electronic dental records (EDR) are also used, EHR is generally used to indicate certified technology systems.

Patient File Envelope or Folder for Paper Records

Most dental practices use an  × 11-inch file envelope or folder to contain clinical paper documents. Records of treatment for transient or one-time patients may be kept together in one folder or file location. File envelopes may be plain or color-coded. They are supplied in a preprinted format with spaces for patient information, including the patient’s name, address, and telephone number (Figure 7-8). This type of envelope is widely used, and it satisfies the needs of many practices.

× 11-inch file envelope or folder to contain clinical paper documents. Records of treatment for transient or one-time patients may be kept together in one folder or file location. File envelopes may be plain or color-coded. They are supplied in a preprinted format with spaces for patient information, including the patient’s name, address, and telephone number (Figure 7-8). This type of envelope is widely used, and it satisfies the needs of many practices.

Another very common type of storage for paper records is an end-tab file folder with one or two two-hole fasteners (Figure 7-9). This type of folder requires the use of vertical-style records. The folders generally have a reinforced tab for easy label placement. They are also precut for the quick insertion of a two-hole file fastener. Options include folders with pockets and diagonal cuts, expandable folders, and polyvinyl pockets to hold small materials such as radiographs and CDs.

Whether folders or envelopes are used, some form of color-coding is necessary to make sorting, storing, and retrieval easier. Color-coding can be done as an alphabetical system, or, in a group practice, it can be used to categorize by dentist. In addition to a label with the patient’s name, either an alpha or numeric label system can be used to sort the records. Year aging labels can be used to identify inactive patient records that may need to be purged from the active storage system.

Patient Registration and Health History Forms

Although they are often combined, these two forms contain two different types of data. The information gathered on these forms should be retained in the patient’s paper file or by scanning the completed form into a computer. Generic paper forms are available from dental forms suppliers. Custom forms can be designed by most companies at an additional cost to address the special needs of a specific office. Electronic versions of these forms are also available.

Some forms address privacy issues with questions such as, “May we leave a message on your answering machine at the phone number you have given?” or “May we contact you at a cell phone number or text message you?” Most supply companies provide patient forms in English and Spanish versions for use in various areas of the country. Many offices with Spanish-speaking patients have both versions available.

The patient registration form contains general information such as addresses, telephone numbers, and e-mail address as well as employment and insurance information (Figure 7-10

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses