In this article, current literature on fixed and removable prosthodontics is reviewed along with evidence-based systematic reviews, including advice from those in the dental profession with years of experience, which help restorative dentists manage and treat their cases successfully. Treatment planning for restorative implantology should be looked at in 4 sections: (1) review of past medical history, (2) oral examination and occlusion, (3) dental imaging (ie, cone-beam computed tomography), and (4) fixed versus removable prosthodontics. These 4 concepts of treatment planning, along with proper surgical placements of the implant(s), result in successful cases.

Key points

- •

More than 30 million Americans are missing all of their teeth, according to the American Academy of Implant Dentistry.

- •

More than 5 million implants are inserted annually in the United States.

- •

Patients are demanding fixed prosthodontics as opposed to removable prosthodontics.

- •

In the completely edentulous patient and some partially edentulous patients, implants have become the treatment of choice. To meet these demands, the restorative dentist should have a good foundation in fixed and removable prosthodontics, to have continued success in restorative implantology.

- •

The goal is to deliver the best implant crown or prosthesis for the patient.

- •

If problems occur along with increased office visits, patients can become frustrated and discouraged.

- •

Treatment planning for restorative implantology should be looked at in 4 sections: (1) review of past medical history, (2) oral examination and occlusion, (3) dental imaging (ie, cone-beam computed tomography), and (4) fixed versus removable prosthodontics. These 4 concepts of treatment planning, along with proper surgical placements of the implant(s), result in successful cases.

More than 30 million people Americans are missing their teeth, according to the American Academy of Implant Dentistry. Misch commented that “more than 5 million dental implants are inserted each year in the United States” and “more than $1 billion in implant products was sold in the United States in 2010.” Implantology (surgical or restorative) is practiced by general dentists, prosthodontists, oral surgeons, periodontists, and endodontists. The restorative dentist should have a good foundation in fixed and removable prosthodontics to have continued success in restorative implantology. Wood and Vermilyea stated “it is imperative that the dentist restoring the implants, after consultation with appropriate specialists, be responsible for the treatment planning.”

The restorative dentist should discuss the case with the surgeon (by telephone, in person, or via written form). There should not be any confusion regarding the implant system being used and the parts needed. Before consents are signed, the restorative dentist should make sure that they have the tools needed to restore the case. The surgeon and clinician should maximize the exchange of information regarding the surgery. The restorative dentist should inquire about (1) if there were any surgical complications, (2) insertion torque, (3) if there was a need for bone grafting or sinus lift, (4) the size/diameter of the platform and length of the implant, (5) the implant manufacturer, (6) the estimated time of placement of the healing cap, and (7) the clearance from the surgeon to begin the restorative treatment. When there is teamwork between the surgeon, restorative dentist, and the laboratory technician, the result can be a masterful replica of a normal oral cavity. The untrained eye simply does not know the difference.

All responsibilities fall in the lap of the surgeon and restorative dentist. All discussions should be finalized with the patient so that they understand the risks, benefits, and options/alternatives from a surgical and restorative standpoint. Lewis and Klineberg stated that “patients should be informed of the spectrum of potential complications and maintenance issues that can occur with implant-borne prostheses, and informed of the biological consequences and associated future costs.” Klein went further in saying “Patient expectations of treatment time, provisional prosthesis requirements, and esthetic demands should be discussed.” Dentistry’s covenant of trust begins by stating “The dental profession holds a special position of trust with society… the profession makes a commitment to society that its members will adhere to high ethical standards of conduct.” The patient’s health, well-being, comfort, and peace of mind should always be at the forefront of any dental services rendered.

Patients should know in advance approximately how many office visits are involved and should be given a cost for the restoration(s), including parts. A frustrated patient does not refer others and could seek legal action if they are stuck with a bill and the final outcome was not delivered as promised. The restorative dentist should be careful about what they say or promise to a patient; it is best not to promise anything. In this chapter, treatment planning for restorative implantology there will be four sections: (1) review past medical history, (2) oral examination and occlusion, (3) dental imaging (ie, cone-beam computed tomography [CBCT]), and (4) fixed versus removable prosthodontics. These 4 concepts of treatment planning, along with proper surgical placements of the implant(s), result in a successful implant cases ( Fig. 1 ). The fifth concept, dental implant surgery will be discussed in the other chapters of this book.

There are many philosophies that differ and create debates among the groups of specialists mentioned earlier. Quality dentistry should be documented daily and incorporated into the practice of implant dentistry to provide successful cases and patient satisfaction. In this article, current literature is reviewed, along with evidence-based systematic reviews (to eliminate bias views), including advice from those in the dental profession with years of experience, which helps the restorative dentist manage and treat their cases successfully.

Review of past medical history

It is prudent for the clinician to review each patient’s medical history, which often sets the stage for the treatment to be delivered. The dentist who chooses not to treat those patients who are medically complex or compromised should consider referring them to those in the profession who believe that they have sufficient training in management of their conditions. Lengthy and complex implant cases may not be suited for patients with multiple medical disorders in the ambulatory setting, so good judgment is needed with these patients. This group of patients may be better managed in a hospital setting, particularly in the operating room (OR). This is not difficult for oral surgeons and hospital dentists who place implants and who have OR privileges. An anesthesiologist can properly induce general anesthesia, monitor the patient’s vital signs, and administer several medications intravenously (for the benefit of the induced patient), which allows the surgeon to focus on the precise details of preprosthetic surgery or implant placement. Most preprosthetic procedures (soft tissue, some bony) can be performed in the ambulatory setting, whereas more complex procedures (ie, vestibuloplasty, floor-of-the-mouth lowering, skin/mucosal/bone grafts, and multistage reconstructive surgery) require treatment in the OR, with overnight observation in a hospital.

A similar concept applies to patients seeking the restoration of implants. If the general dentist does not feel confident that they can restore the implants, they have the ethical responsibility to refer the patient to someone in the profession who can properly manage the case (ie, a prosthodontist). The reasons include the length of chair time, the cost of the restoration(s), and the number of visits involved. Henry and Liddelow recommended that inexperienced operators should use conventional loading protocols (instead of immediate loading) and that patient-mediated factors (eg, uncontrolled diabetes, parafunctional habits, smoking) should be regarded as contraindications to immediate loading, and so forth.

Patients are living longer, and many taking multiple medications for chronic conditions are in need of dental care. Some of these patients demand fixed prosthodontics as opposed to removable prosthodontics. Such demands present challenges to the dentist, regardless of the specialty. The patient who can obtain rehabilitative restorations or prostheses of greater than 60% of there lost dentition can have a good quality of life. The ability to chew (masticate) foods properly means that a patient can swallow, digest, and excrete foods normally, therefore eliminating the possibility of choking by trying to swallow a bolus, which can also lead to a host of digestive problems. Greenberg and colleagues stated that “Oral health is an integral part of total health, and oral health care professionals must meet the advances in medicine, in order to be at the forefront of the overall health care team.” The patient interview of the history is the most important part of the diagnostic patient workup, because it is imperative for the clinician to properly diagnose, collect data (ie, laboratory tests), consult with primary care physician/MD or specialists, and allow for the development of a good doctor-patient relationship. The medical history comprises a systematic review of the patient’s chief complaint, information about past and present medical conditions, pertinent social and family histories, and a review of systems.

Marder stated that dentists must use intelligence, common sense, and physician consent for the proper treatment of medically compromised patients. He also added that when there is “deterioration of general health, increased risk of infection, prolonged bleeding, or even demise exists, it is best to defer treatment until systemic stability or disease remission has been accomplished – and never without consultation with a physician.”

Several studies have established the negative effect of tobacco use on implant success and the likelihood of failure after second-stage surgery. Every clinician should be knowledgeable about different risk factors that can undermine the success of the implant. Table 1 includes a list of notable medical conditions that should raise warning flags or caution before implant placement.

| Moderate to severe neutropenia | Psychological instability |

| Patients on corticosteroids | Radiation therapy |

| Chemotherapy | Coronary artery disease (ie, myocardial infarction within 6 mo) |

| Osteoporosis (patients on intravenous bisphosphonates) | Gravid patient |

| Poorly controlled diabetes | Heavy smoking habits |

| Malignancy/terminal illness | Cluster phenomenon |

The term cluster phenomenon was used to describe a group of patients with implant failures with multiple systemic disorders and medications that include but are not limited to osteoporosis, diabetes, mental depression, heavy smoking habits, and parafunctional mandibular movements. Parafunctional habits include tooth clenching, grinding, biting on pencils, chewing on ice, or bruxism. Balshi reported that “overload caused by improper prosthesis design or parafunctional habits is considered to be one of the primary causes of late-stage implant failure.”

Review of past medical history

It is prudent for the clinician to review each patient’s medical history, which often sets the stage for the treatment to be delivered. The dentist who chooses not to treat those patients who are medically complex or compromised should consider referring them to those in the profession who believe that they have sufficient training in management of their conditions. Lengthy and complex implant cases may not be suited for patients with multiple medical disorders in the ambulatory setting, so good judgment is needed with these patients. This group of patients may be better managed in a hospital setting, particularly in the operating room (OR). This is not difficult for oral surgeons and hospital dentists who place implants and who have OR privileges. An anesthesiologist can properly induce general anesthesia, monitor the patient’s vital signs, and administer several medications intravenously (for the benefit of the induced patient), which allows the surgeon to focus on the precise details of preprosthetic surgery or implant placement. Most preprosthetic procedures (soft tissue, some bony) can be performed in the ambulatory setting, whereas more complex procedures (ie, vestibuloplasty, floor-of-the-mouth lowering, skin/mucosal/bone grafts, and multistage reconstructive surgery) require treatment in the OR, with overnight observation in a hospital.

A similar concept applies to patients seeking the restoration of implants. If the general dentist does not feel confident that they can restore the implants, they have the ethical responsibility to refer the patient to someone in the profession who can properly manage the case (ie, a prosthodontist). The reasons include the length of chair time, the cost of the restoration(s), and the number of visits involved. Henry and Liddelow recommended that inexperienced operators should use conventional loading protocols (instead of immediate loading) and that patient-mediated factors (eg, uncontrolled diabetes, parafunctional habits, smoking) should be regarded as contraindications to immediate loading, and so forth.

Patients are living longer, and many taking multiple medications for chronic conditions are in need of dental care. Some of these patients demand fixed prosthodontics as opposed to removable prosthodontics. Such demands present challenges to the dentist, regardless of the specialty. The patient who can obtain rehabilitative restorations or prostheses of greater than 60% of there lost dentition can have a good quality of life. The ability to chew (masticate) foods properly means that a patient can swallow, digest, and excrete foods normally, therefore eliminating the possibility of choking by trying to swallow a bolus, which can also lead to a host of digestive problems. Greenberg and colleagues stated that “Oral health is an integral part of total health, and oral health care professionals must meet the advances in medicine, in order to be at the forefront of the overall health care team.” The patient interview of the history is the most important part of the diagnostic patient workup, because it is imperative for the clinician to properly diagnose, collect data (ie, laboratory tests), consult with primary care physician/MD or specialists, and allow for the development of a good doctor-patient relationship. The medical history comprises a systematic review of the patient’s chief complaint, information about past and present medical conditions, pertinent social and family histories, and a review of systems.

Marder stated that dentists must use intelligence, common sense, and physician consent for the proper treatment of medically compromised patients. He also added that when there is “deterioration of general health, increased risk of infection, prolonged bleeding, or even demise exists, it is best to defer treatment until systemic stability or disease remission has been accomplished – and never without consultation with a physician.”

Several studies have established the negative effect of tobacco use on implant success and the likelihood of failure after second-stage surgery. Every clinician should be knowledgeable about different risk factors that can undermine the success of the implant. Table 1 includes a list of notable medical conditions that should raise warning flags or caution before implant placement.

| Moderate to severe neutropenia | Psychological instability |

| Patients on corticosteroids | Radiation therapy |

| Chemotherapy | Coronary artery disease (ie, myocardial infarction within 6 mo) |

| Osteoporosis (patients on intravenous bisphosphonates) | Gravid patient |

| Poorly controlled diabetes | Heavy smoking habits |

| Malignancy/terminal illness | Cluster phenomenon |

The term cluster phenomenon was used to describe a group of patients with implant failures with multiple systemic disorders and medications that include but are not limited to osteoporosis, diabetes, mental depression, heavy smoking habits, and parafunctional mandibular movements. Parafunctional habits include tooth clenching, grinding, biting on pencils, chewing on ice, or bruxism. Balshi reported that “overload caused by improper prosthesis design or parafunctional habits is considered to be one of the primary causes of late-stage implant failure.”

Dental imaging: radiographs/cone-beam computed tomography

Oral rehabilitation is a term that takes on different circumstances and meanings to specialists in the dental profession. The responsibility for implantology is shared by the surgeon (ie, oral surgeon, prosthodontist, periodontist, perioprosthetic specialist, endodontist, and general dentist/implantologist) and restorative dentist (ie, prosthodontist, periodontist, and general dentist/implantologist). Traditionally, the restorative dentist initiated the consultation and recommended the region for the implant, then referred the patient to the oral surgeon, who then placed the implant(s). There are more dentists and specialists who are placing and restoring the implant(s). If the traditional planning for implant placement is used, then, there must be excellent communication between both doctors. As mentioned earlier, it is important that the same implant system is used and agreed, to eliminate any problems.

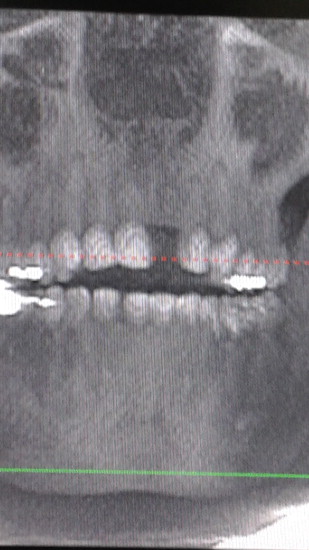

The oral and maxillofacial radiologist is often forgotten but has been instrumental in the transition from conventional radiology to CBCT. Preoperative consultation with an oral and maxillofacial radiologist can be helpful especially when there is a need to rule out and interpret disease (especially intraosseous disease). The surgeon must be cautious of certain anatomic structures in the maxilla and mandible before implant placement, such as the inferior alveolar nerve (IAN), mental nerve, nasopalatine canal, bony defects found on the facial surface of maxillary anteriors, the lingual concavity of the mandible, and pneumatization of the maxillary sinus. These common findings in the human anatomy can place the surgeon at risk of injuring the lingual nerve or IAN, resulting in neuropraxia, axonotmesis, or neurotmesis, and leading to neuropathy, paresthesia, or anesthesia, respectively. Soderstrom and colleagues stated that “the type, orientation, and amount of available bone and its orientation are crucial in treatment planning for implant location”; therefore, a variety of radiographic techniques may be implemented to obtain the best placement. Many dentist or oral surgeons in private practice may not have CBCT, because of cost; therefore, they have to depend on panoramic and periapical radiograph(s). Mupparapu and Beideman made an important note that “panoramic radiographs are not to be used for specific anatomic measurements because of uneven (10% to 30%) magnifications within different regions of the image.” The anatomic findings must be well understood before implant placement to prevent errors. The use of CBCT may be overemphasized, because there are times when patients seem to have sufficient bone (mesiodistally) with conventional film; however, after the use of CBCT, the patient may not have adequate bone for an implant buccolingually, which can lead to perforations or fenestrations, which can result in failure (see Figs. 2–4 ). In cases similar to this, patients may opt to have adjunctive surgical procedures or settle for fixed bridge or a removable appliance. Adjunctive treatments, such as onlay bone grafting/guided tissue regeneration, sinus lift, distraction osteogenesis, and ridge splitting, can be performed by the surgeon to overcome anatomic challenges. The following adjunctive procedures can bring additional costs to the patient. Every treatment plan should be made according to the patient’s budget; therefore, all fees should be discussed in advance, so that the patient can decide if they can afford the package. It is imperative that all risks, benefits, and options/alternatives are discussed with the patient before implant placement.