Lymphangioma of the tongue causes massive tongue enlargement, leading to difficulties in swallowing and mastication, speech disturbances, airway obstruction, and skeletal deformities such as open-bite malocclusion. Early reduction of tongue volume improved the excessive open bite in a young girl, but it was not sufficient to redirect the original hyperdivergent growth pattern. Orthodontic camouflage treatment was therefore rendered. Long-term evaluation after tongue-reduction surgery and orthodontic treatment is presented.

An open bite develops from a combination of dental, skeletal, and environmental factors. Although simple open bites caused by dental factors are relatively easy to correct with favorable outcomes, open bites with skeletal components are usually more difficult to treat with less stable results. Environmental factors, including aberrant neuromuscular function of the lip or tongue, abnormal tongue posture, and airway obstruction, can also increase the risk of open bite. Therefore, proper identification of the etiology and careful diagnosis are important in achieving optimal treatment results. Here, we report the long-term outcome of an open-bite malocclusion with macroglossia due to tongue lymphangioma and hyperdivergent growth treated with serial tongue-reduction surgeries and orthodontic camouflage treatment.

Diagnosis and etiology

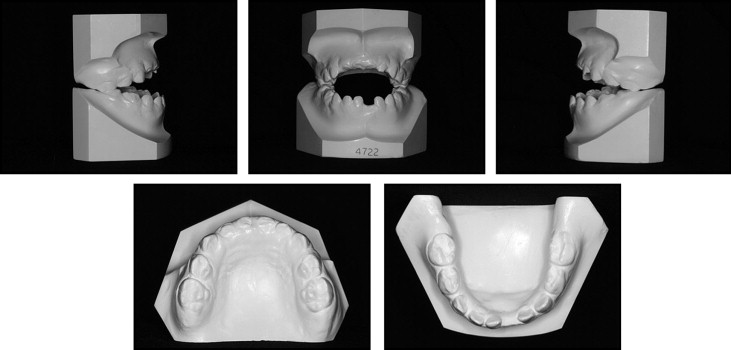

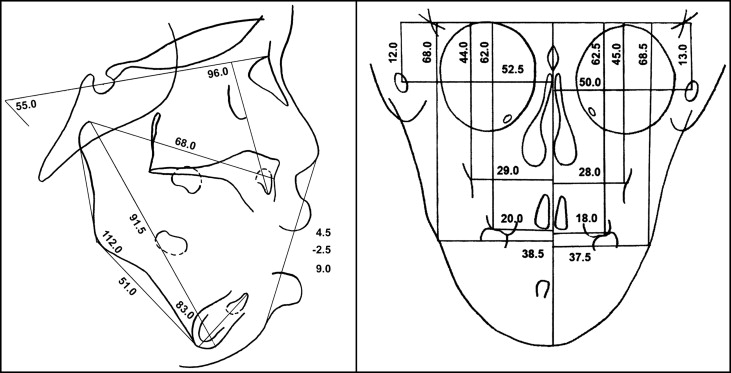

A girl, aged 3 years 5 months, came to the Department of Orthodontics, Gangnam Severance Dental Hospital, Yonsei University, in Seoul, Korea, seeking orthodontic treatment. She had been diagnosed with lymphangioma of the tongue. Macroglossia caused her to drool and have breathing difficulty. She also had a dental history of abnormal tongue posture. She had a convex profile with increased lower facial height and severe anterior open bite (−13 mm). The deciduous second molars were the only teeth that were occluding. Several carious lesions were present in the maxillary arch ( Figs 1 and 2 ). The panoramic radiograph showed a supernumerary tooth between the maxillary central incisors. Lateral cephalometric analysis confirmed a skeletal Class II open bite with increased lower facial height. The posteroanterior cephalometric radiograph showed slight mandibular asymmetry but otherwise was within normal limits ( Figs 3 and 4 , Table ).

| Age | Initial | Pretreatment | Posttreatment | 1-year retention |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3 y 5 mo | 12 y 1 mo | 13 y 10 mo | 14 y 10 mo | |

| SNA (°) | 84.5 | 78.0 | 76.0 | 77.0 |

| SNB (°) | 74.5 | 73.5 | 72.0 | 73.0 |

| ANB (°) | 10.0 | 4.5 | 4.0 | 4.0 |

| Wits (mm) | −2.5 | 3.0 | −1.5 | −3.0 |

| Gonial angle (°) | 112.0 | 135.5 | 135.5 | 135.0 |

| SN-MP (°) | 55.0 | 55.5 | 55.5 | 54.0 |

| FMA (°) | 45.8 | 45.3 | 46.3 | 46.2 |

| Posterior facial/anterior facial height | 52.3 | 54.7 | 55.4 | 55.3 |

| Ramus height (mm) | 31.9 | 41.4 | 45.6 | 46.4 |

| Overbite depth indicator | 52.8 | 55.5 | 58.3 | 64.5 |

| U1 to SN (°) | 96.0 | 120.0 | 98.5 | 102.0 |

| IMPA (°) | 83.0 | 66.5 | 72.0 | 76.0 |

The primary cause of the open bite was evidently related to the macroglossia of the tongue due to lymphangioma. Lingual lymphatic malformation is frequently localized in the anterior two thirds of the tongue and enlarges to a great extent after an episode of upper respiratory tract infection. As the tongue swells, it can cause difficulties in swallowing and mastication, speech disturbances, airway obstruction, and deformities of maxillofacial structures. Surgical removal is the treatment of choice when the lymphangioma interferes with esthetics or function. Spontaneous regression of anterior open bite after glossectomy has been reported in several patients, and self-correction has also been described throughout the growth period. We believed therefore that a decrease of the anterior open bite could be expected after reduction of the tongue volume in our patient. However, the effects of a glossectomy on the vertical skeletal pattern or changes during facial growth are not yet fully understood.

Treatment objectives

The main treatment objectives were to regain proper function and to improve the occlusion early as possible. For these goals, reduction of excess tongue volume was of paramount importance. If the hyperdivergent growth pattern remained, growth modification followed by camouflage or surgical orthodontic treatment would also be necessary to achieve ideal esthetics and function.

Treatment objectives

The main treatment objectives were to regain proper function and to improve the occlusion early as possible. For these goals, reduction of excess tongue volume was of paramount importance. If the hyperdivergent growth pattern remained, growth modification followed by camouflage or surgical orthodontic treatment would also be necessary to achieve ideal esthetics and function.

Treatment alternatives

To improve perioral function and to correct the open bite caused by the enlarged tongue, surgical excision of the lesion and tongue-reduction surgery were indicated. Spontaneous changes in occlusion after tongue reduction and continued eruption of the permanent dentition were expected, so careful follow-up of growth was planned before considering any active orthodontic treatment. Surgical extraction of the supernumerary tooth was also advised before the eruption of the maxillary central incisors.

If the hyperdivergent growth pattern remained during the follow-up period, several methods for growth modification could be considered. In patients with long-face syndrome combined with a Class II skeletal growth pattern, a high-pull headgear or a maxillary splint could be used to prevent excessive vertical growth. Another option would be to use functional appliances combined with a high-pull headgear for maximum vertical growth control.

Based on the severity of the vertical skeletal problems and the amount of remaining open bite after growth observation and modification, camouflage treatment with a fixed appliance accompanied by either nonextraction or extraction or surgical correction could be considered to achieve ideal esthetics and function.

After a series of tongue surgeries, the patient and the parents were clearly reluctant to accept additional surgical treatment. Therefore, growth modification with headgear during the growth period was emphasized, followed by orthodontic camouflage treatment.

Treatment progress and results

The patient had several tongue-reduction surgeries before she was 9 years old. Progressive open-bite closure could be seen after the tongue-reduction surgeries; this implied that the macroglossia was a major etiologic factor for the extreme open bite. The supernumerary tooth was also surgically extracted.

By the time the patient was 10 years 4 months old, all permanent teeth except the maxillary and mandibular right canines had erupted. The skeletal age of the patient reached stage 3 of the skeletal maturity index of Fishman at this point. Since a hyperdivergent growth pattern was evident even after the decrease in open bite, orthopedic growth modification with a maxillary splint and high-pull headgear was attempted before the growth peak started at skeletal maturity stage 4. There was dental midline deviation to the right (2 mm) with a lack of canine space on the right side, leaving both maxillary and mandibular canines impacted ( Fig 5 ). Considering the amount of space needed for the canines with correction of the midline and the large overjet (8.0 mm), first premolar extractions were indicated. The maxillary and mandibular right first premolars were extracted first to guide the canines to erupt along with continuous use of the high-pull headgear. However, the patient did not comply well with the appliance, and there was little orthopedic effect, if any. Cephalometric superimposition throughout the period confirmed the persistent hyperdivergent skeletal growth pattern ( Fig 6 ).