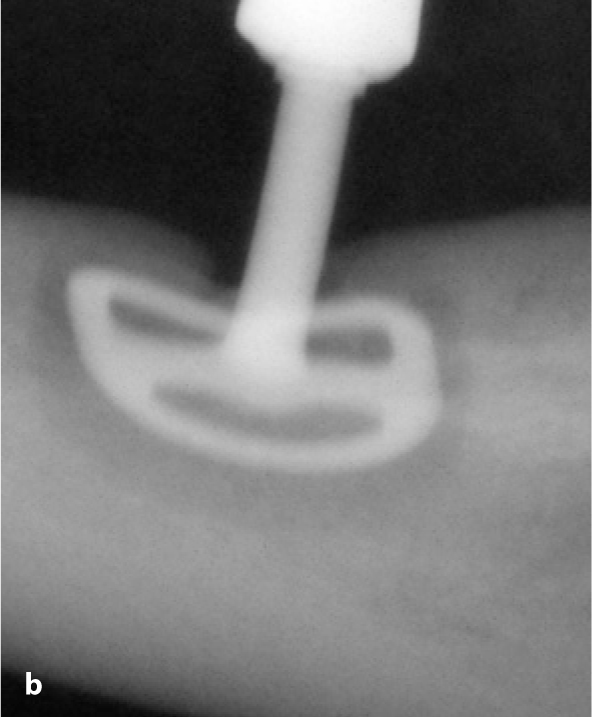

Fig. 15.1.

This mandible was treated by positioning four BOI implants in strategic positions. Note that the base plates of the two anterior implants are positioned below the mental nerve. The distal implants have been positioned slightly above the nerve. 5 yrs. postoperative picture; the implants have been equipped with the definitve bridge within 24 hours.

Each implant transmits a different component of the overall flexural force to the implant-restoration system, exerting an influence on the other implants as well.

Particular problems are posed by implants located in the premolar region. Due to the caudal torsion of the mandible when the mouth is opened, these constitute a hypomochlion resulting in additional undesirable forces acting on all disks. Those disks that bear the brunt of all other forces (masticatory forces, flexural forces) have the greatest tendency toward demineralization, ultimately resulting in complete detachment from the bone in some cases. The life expectancy of premolar BOI is also reduced by the fairly high probability of the lingual aspect of the disk losing contact with the cortical bone. The reason for this relative repositioning of the integrated implant in space is the lingual bone apposition that occurs in true bone modelling as a response to the change in shape that occurs in the region of the curvature of the horizontal mandibular ramus, a change ultimately caused by the osteotomy of the mandible. Of course, this relative repositioning must also be seen as a response to increasing masticatory forces. These added forces will tend to preserve the newly formed bone and increasingly result in mineralization.

15.2.2 Strategic Implant Positioning

If the patient was treated using the technique of basal osseointegration (Ihde 2001), the technique preferred by us, only a few implants will be strategically positioned. Here, four implants will usually be inserted at 47, 43, 33 and 37 for fixed restorations. Although the basal aspects of the implants that transmit the loads will of course osseointegrate, these jaw-implant-restoration systems will act flexibly; the threaded pins will serve as a flexible interface between the load-transmitting osseointegrated disks on one hand and the bridge on the other, with the bridge remaining rigid.

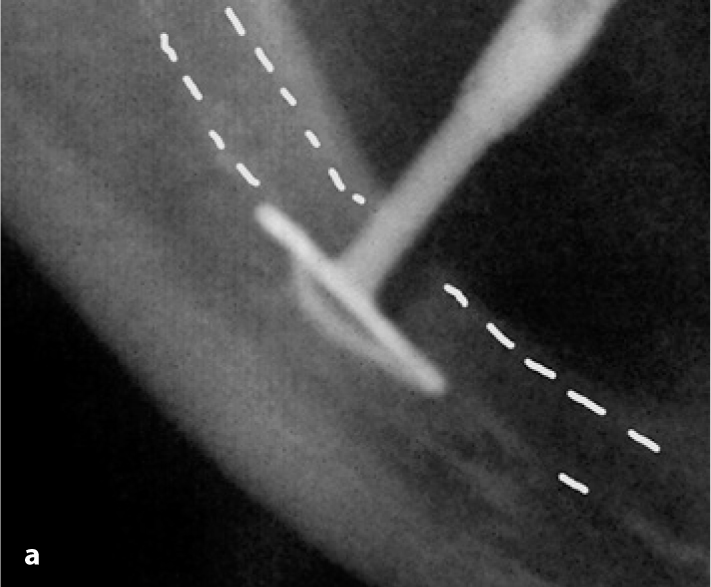

Fig. 15.2.

a Extremely atrophied mandible with four strategically positioned BOI implants as abutments. The implant at 37 does not show circumferential mineralization; however, it is not mobile. Once again, the anterior disks were placed infranervally. b The peri-implant bone substance in this radiograph close-up appears darker than the surrounding bone. The darker region is not clearly delimited; the insertion slot exhibits no bony closure at this point (2 years postoperatively) and is not likely to be closed in the foreseeable future. The implant is fully functional and must not be removed under any circumstances. In a mandible that combines severe atrophy and high bone elasticity, the degree of mineralization in the interfacial region cannot be expected to be higher; this radiograph thus shows the best possible treatment result for the particular case at hand. c, d Example of strategic implant positioning in the mandible. The threaded pins of the anterior implants are usually located lingually of the teeth. The abutments are left to protrude throughout the fabrication of the superstructure in the dental laboratory and are not trimmed until after definitive cementing

This strategic positioning creates an acceptable tension between the implant sites during use, with the fixed restoration always absorbing and compensating for some of the tensional load. Bone will grow between the implants (something that is easier to measure in the mandible than in the maxilla) vertically above and below the disks (see Fig. 9.9). The increase in bone volume is caused by the increase in masticatory forces and will appear particularly pronounced in cases in which the pressure previously exerted by the patient’s removable denture is removed.

Bacterial attacks at the insertion sites, i.e. the sites of mucosal penetration, play a very insignificant role in BOI, which means that the bone volume can grow largely unrestricted, following only functional requirements. Eventually, of course, this bone growth will be stopped by the fixed restoration pontics.

By contrast, bone volume can hardly increase in a crestal direction in the case of implant-restoration systems comprising a large number of implants. If implant location is determined by other than just strategic considerations, comprehensive interface contact predominates, and the shape of the bone changes only in the horizontal dimension, if at all. Disks without surface enlargement tend to be recommended for this type of restorations, because no friction is created in cases where osseoadaptation is absent around certain areas of the disks or during certain limited periods. One cannot expect all areas of the disk to be firmly integrated, with a high degree of mineralization, at the same time, given the extremely flexible environment of the atrophied mandible. In some cases, even four BOI implants might render the atrophied mandible unduly rigid.

While the atrophied mandible usually lacks enough vertical bone volume for the insertion of crestal implants, it will often still offer sufficient bone volume in the horizontal dimension. Whether this is in fact the case can be verified by palpitation. This bone supply is optimally utilized by horizontally inserted implants of the BOI type. In the past we always tried to insert a maximum of basal implants in the mandible, following general implantological fashion as well as the French school. The biomechanical reaction of the mandible has taught us that treatment can be at least as successful if fewer implants are used. Generally speaking, two to three implants may be inserted in the anterior region. In the distal regions of the mandible, one implant per quadrant can be used.

If more implants are inserted, the macrotrajectorial structure of the mandible is weakened, something that we subjectively judge to be a disadvantage, especially since one has to expect that the morphology of the atrophied mandible changes more substantially following implantation that that of a mandible in which the bone supply is better.

15.2.2.1 Anterior Implants

As long as sufficient vertical space is available, EDD(S) 9/7 G7 or EDD 10/7 G6 tend to be used. If the insertion of double disks is not successful, size 9S G9, 9S G8 or even 9S G6 can be used instead. We avoid smaller disks wherever possible; larger disks are usually not required. Triple-disk BOI implants have proven to be very useful in the anterior region of the mandible.

15.2.2.2 Posterior Implants

Depending on the amount of available vertical and horizontal bone volume, EDAS 9/12 G7 or EDAS 9/15 G5 will be used. Generally, EDAS implants work very well for this indication, since the threaded pin always ends up in a prosthodontically favourable medial position when inserted laterally. This allows the centripetal resorption of the mandible to be partially compensated for as early as during implantation. The longitudinal shape of the implant yields excellent primary stability, and even wider mandibles usually no longer require the use of large-disk, rotationally symmetrical BOI implants; minimally invasive implant bed preparation will be sufficient.

Experience shows that all situations in the posterior mandible can be managed using these two implant types and – occasionally – with other EDAS implants. The best implant site is the anterior edge of the ascending mandibular ramus, which is strongly mineralized, as can easily be seen in radiographs of the region. Implants inserted at the end of the slope or below the “white line” (in the orthopantomograph) are almost never lost, at least not as long the line does not shift its functionally determined position.

From a prosthodontic point of view, complete bridge restorations are inserted in both procedures. In our experience, “tooth-by-tooth” implantation as used to be common in crestal implantology constitutes an unnecessary treatment cost factor. It is not so much the occlusion that requires adjustment as adjusted as the gliding movement of the teeth past each other, as known from complete dentures in humans or tooth ridges in birds (Ihde 1911).

15.3 Infranerval Implantation

If the vertical bone supply above the mandibular nerve is less than 2 mm, infranerval implant insertion is indicated. EDAS implants are mostly unsuitable for this purpose, since the nerve would end up being located too far vestibularly. Rather, the unilaterally cubical EDS implants (often 9S G6, 9S G8) or the older round implants (9 G8 or 7 G8) are used. For an experienced implantologist, the technique of infranerval implant insertion is no more difficult than supranerval insertion: A sharp bone-cutting bur or round bur is used to open the nerve canal in the bone and to expose the nerve. It is important to explore the caudal extension of the nerve canal in order to prevent subsequent encroachment on or trauma to the nerve, which might migrate in a caudal direction under certain circumstances, caused by the cutting instrument. If the nerve canal is not limited in a caudal direction by bone, the risk of damage to the nerve is particularly high. If the nerve is located sufficiently far to the lingual side within the area selected, the vertical slot is prepared first, from vestibularly, followed by a second infranerval horizontal implant slot. If the nerve, when first exposed, is located too far vestibularly, a different and more suitable implant site will have to be found more distally. In our experience, insertion from vestibularly will always be successful in actual clinical practice; after all any mandibular nerve exits the mandible in a lingual direction. Infranerval insertion from lingually is theoretically feasible, but to date we have never had to resort to this method. Exposure and repositioning of the mandibular nerve is hardly indicated for BOI implants, but it is occasionally practised by some implantologists in selected spatial situations.

The activity in the immediate vicinity of the mandibular nerve canal, especially because of the wide opening of the flap in a vestibular direction (to accommodate an instrument 7–10 mm in diameter in the depth of the vestibulum, approaching the mandible from a lateral direction) and the commonly required traction and slight mobilization of the mandibular nerve often result in postoperative paraesthesia. However, these rarely persist beyond three months, and that only in the region of the chin. Of course, the patient needs to be duly informed of this possibility. In patients with extremely atrophied jawbones, some implantologists proceed as follows to educate their patients: The patient receives a mental nerve block. While the anaesthetic effect still persists, the patient signs a declaration to the effect that he or she can feel the anaesthesia, cannot control the flow of saliva, and has difficulty drinking. The patient further declares that he or she knows these effects to be connected, in the worst of cases, with implantation near the nerve and that these effects, also in the worst case, might be irreversible; furthermore, that in the very worst of all cases, the numbness may persist for a lifetime despite the implant being lost (for unrelated reasons). By their willingness to sign such a declaration, patients demonstrate that the impending implant procedure means a lot to them and that they are ready to accept even extremely unpleasant side effects if this in turn means that their edentulous state and the need to use removable dentures can be treated successfully. Some patients are unwilling to sign this declaration. This would indicate that they are not ready to accept side effects of the type mentioned – and most probably really prefer to keep living with removable dentures.

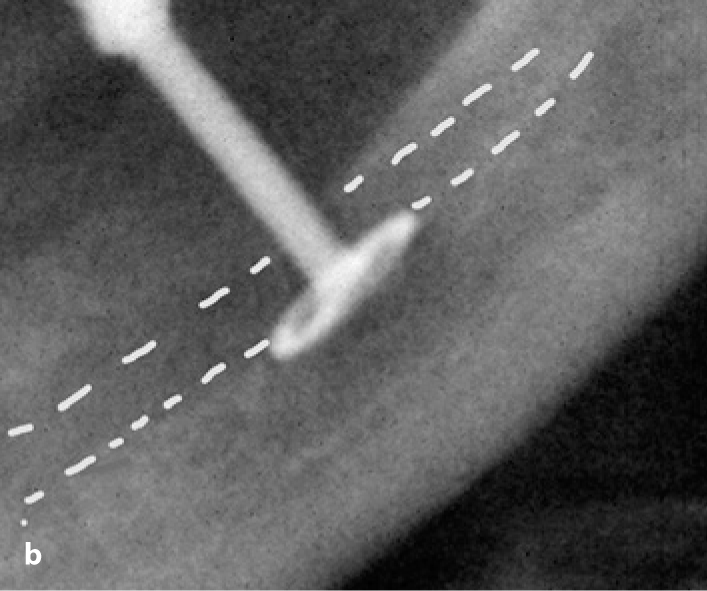

Fig. 15.3a,b.

Two examples of infranerval implantation in BOI technique. The nerve route is indicated by the white dotted lines. In the case shown in b, one would have been able, if only barely, to insert a double-disk BOI implant below the nerve. However, this would have additionally weakened the mandibular structures and increased the risk of fracture. a The implant was additionally moved distally, which is why the vertical insertion slot is clearly visible. This allowed the mesial edge to be adapted more closely. The caudal and vestibular limits of the cortical bone of the nerve canal did not suffer any damage (Video 7 shows the implantation of the implants shown in Fig. 15.3a

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses