Treatment of Inflammatory Periodontal Diseases

• Gingivitis

• Periodontitis

Gingivitis and periodontitis are elicited primarily by bacteria. As a consequence, the treatment must have a primarily anti-infectious nature. Reduction or elimination of the infection results for the most part from mechanical treatment of affected teeth and root surfaces as well as the gingival soft tissue. In special cases, support via topical or systemic medications may be indicated. Alterable risk factors must be eliminated as much as possible.

This section deals with the following constituents of periodontal therapy:

|

• Concepts of periodontal therapy: methods, goals, outcomes • Periodontal healing, treatment planning, course of treatment |

|

| “Phase 0” Therapy | Systemic pre-treatment |

|

• Emergency therapy |

|

| Phase-1 Therapy |

• Initial therapy 1 and 2 Anti-infectious/causal, non-surgical therapy • FMT – “full mouth therapy” |

| • Adjunctive medicinal therapy – systemic and topical | |

| Phase-2 Therapy | Surgical therapy Anti-infectious and corrective therapy • Access flap surgery • Regenerative therapy • Resective therapy • Furcation treatment |

|

• Mucogingival and plastic surgery |

|

| Phase-3 Therapy | Maintenance therapy – recall |

|

• Additional adjunctive therapy: |

|

|

|

• Functional, orthodontic and splint therapy • Perio-prosthetics 1 and 2 • “Alternative” therapy: Dental implants |

Left side:

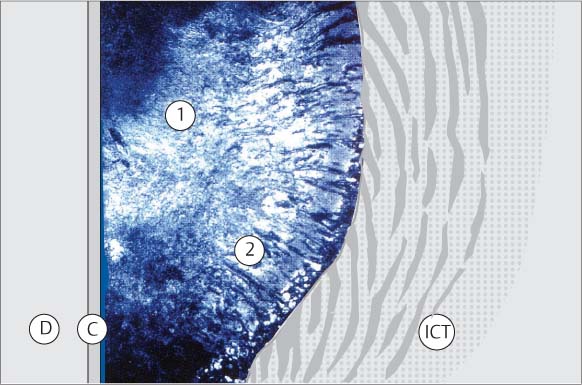

Histologic section in polarized light; True regeneration of the periodontium following GTR (p. 338) M. Hürzeler et al. 1997

1 Dentin

2 New acellular cement, fibers

3 Periodontal fiber apparatus

Courtesy P. Schüpbach

Therapeutic Concepts and Techniques

All of the new knowledge gleaned in recent years, particularly in the areas of etiology and pathogenesis, have led to a true paradigm shift in treatment philosophy. This can be seen in many areas of practice. Following early diagnosis and early treatment, methods of and successes in prevention have become manifest. Only a few years ago, pocket elimination and freedom from plaque stood clearly in the foreground; however, today many other possibilities for combating periodontitis have entered the therapeutic larder.

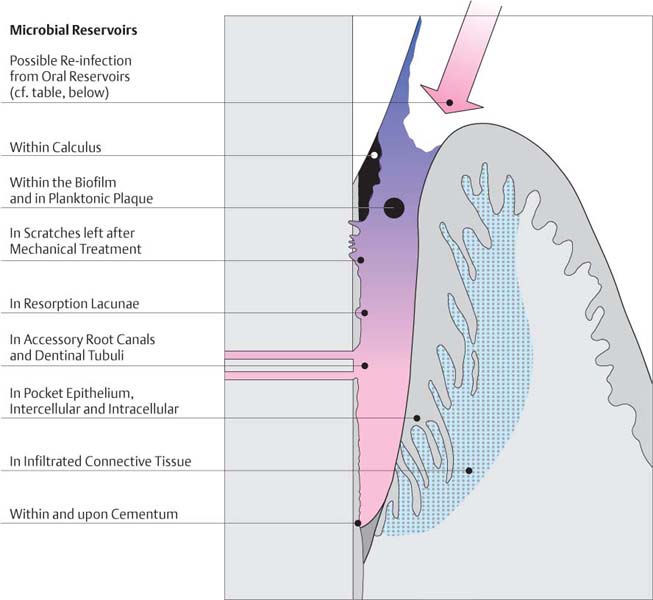

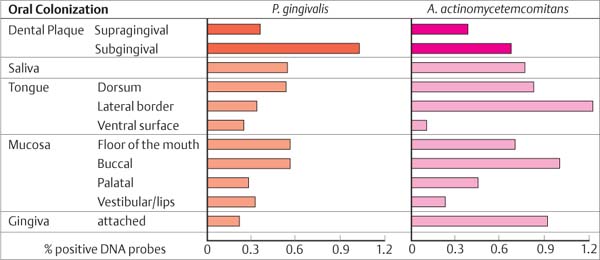

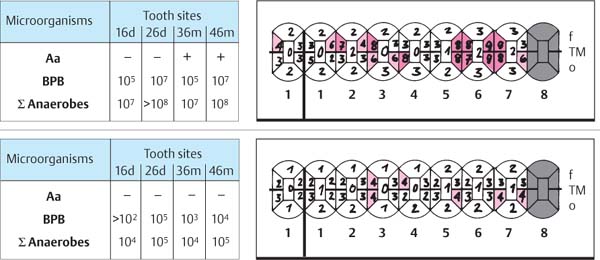

Elimination/Reduction of Pathogenic Bacteria

It is impossible to achieve total freedom from plaque, either supragingivally or subgingivally. Therefore the goal of therapy is not the elimination of periodontopathic microorganisms, but rather “only” a significant reduction of the total number of microorganisms in the oral cavity. The goal is the creation of a homeostatic balance between resident bacteria and the host organism. Non-pathogenic microorganisms may be viewed as beneficial, because they often to maintain periodontopathic microorganisms in check (Fig. 444).

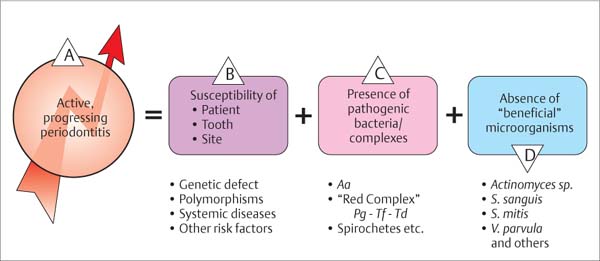

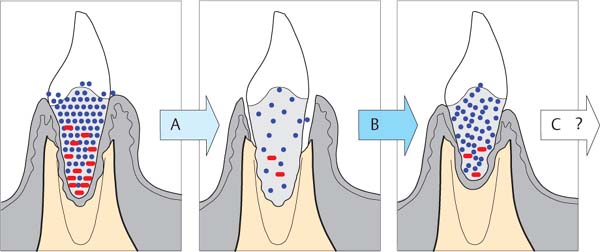

444 Etiology of Progressive Periodontitis

A The progression of periodontitis depends on various factors:

B The susceptibility of the patient (genetic defects or polymorphisms, systemic diseases, additional risk factors)

C The presence of periodontopathic bacteria and…

D … the absence of beneficial microorganisms.

Modified from Socransky & Haffajee 1993

Elimination of the Biofilm—Causal Therapy

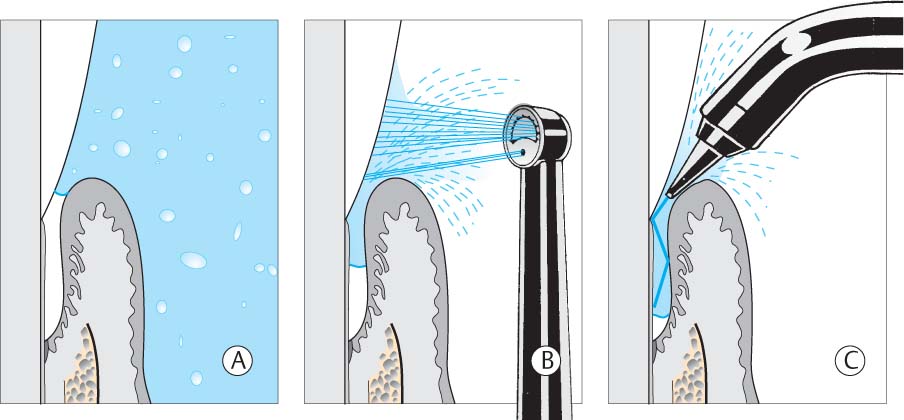

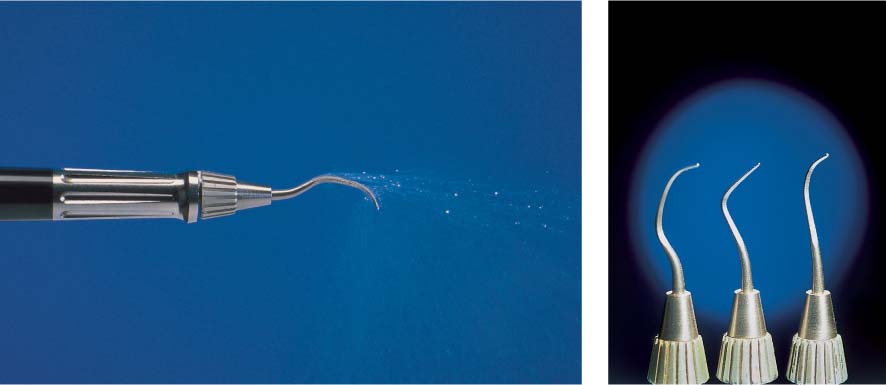

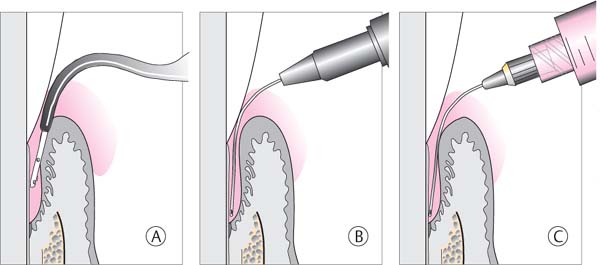

The first step toward such homeostasis is achieved mainly by mechanical disruption of the closed community of microorganisms represented by the biofilm within the periodontal pocket, and the subsequent removal of these microbes. Disrupting the biofilm permits attack by the host defense systems and topical medicaments. This type of pocket treatment, particularly the treatment of the root surface, is performed mechanically either “closed” or “open,” using ultrasonic instruments and/or conventional hand instruments.

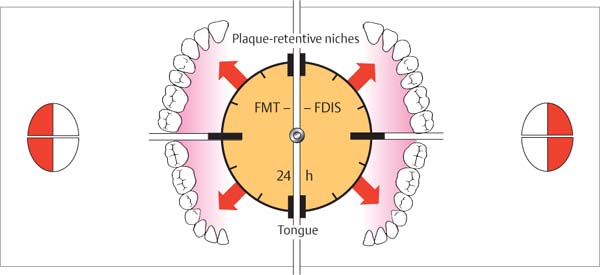

The traditional closed mechanical treatment is particularly effective today when used in the “full mouth therapy” method (FMT; Quirynen et al. 1995, De Soete et al. 2001, Saxer 2002a, b). In the FMT technique, the pockets are continuously rinsed with a disinfectant solution (e.g., CHX, betadine etc.) during root planing. This combined technique improves the therapeutic results significantly, especially when all four quadrants are treated within a 24-hour period of time (p. 281).

Open (surgical) treatment also has as its primary goal the elimination of periodontopathic microorganisms within the biofilm. In addition, any morphologic defects of the bony pocket can be improved or corrected.

Corrective Therapy—Treating the Bony Defects

New knowledge makes it possible to predict regeneration of damaged periodontal structures:

• Filling of hard tissue defects with bone and bone replacement materials

• Using membrane-guided tissue regeneration (or combining both methods)

• Use of signal molecules such as matrix proteins, growth factors etc.

Influencing the Host

Unavoidable (non-alterable) risk factors such as genetic defects cannot be therapeutically influenced today; systemic diseases must, however, be diagnosed and treated by the physician. Thus, for example, a well controlled diabetic can be offered periodontal therapy with a good chance of success.

The patient’s alterable risk factors (p. 54) must also be eliminated or severely reduced.

Protecting the “beneficial” Microorganisms

As mentioned, following periodontal therapy there should exist in the oral cavity an ecological homeostatic balance. In this regard, it is important that if the mechanical therapy is augmented by systemic medications, an antibiotic be selected that does not also eliminate the “useful or beneficial” microorganisms.

Therapy—Problems

The principle of periodontitis therapy is simple: Thorough cleaning of tooth and root surfaces. However, in practice it is often associated with significant problems, among them:

• The irregular contour of the base of the pocket and the remaining junctional epithelium

• The micromorphology of the roots and furcations, especially cellular cementum, cementicles, lacunae and resorptions (Schroeder & Scherle 1987)

• The macromorphology of the roots, with narrow furcations, root fusions, ridges, grooves etc.

Rarely is the bottom of a periodontal pocket identical at all sites around the tooth. Usually some areas of the tooth are more severely involved than others.

The natural root surface is rough, especially in areas with cellular cementum and in furcations. It often exhibits cementicles and enamel pearls, and even in health some lacunae are observed (Schroeder & Rateitschak-Plüss 1983; Schroeder 1986; Holton et al. 1986). Cleaning of such plaque-retentive areas by means of root planing is difficult and time-consuming!

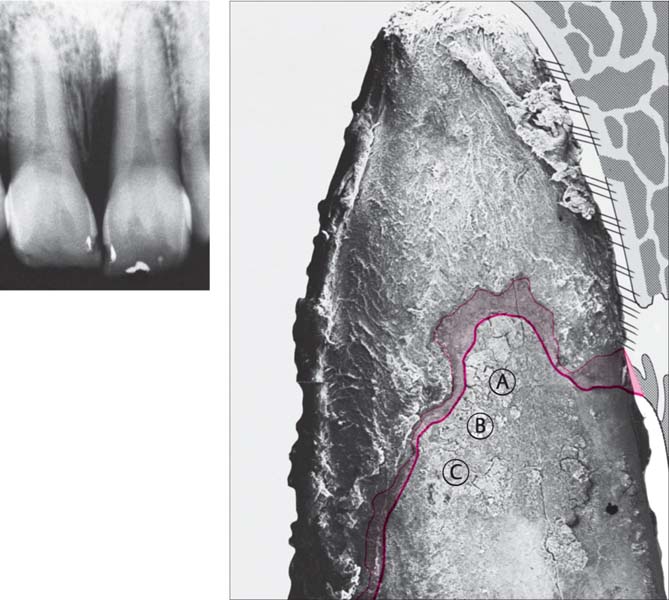

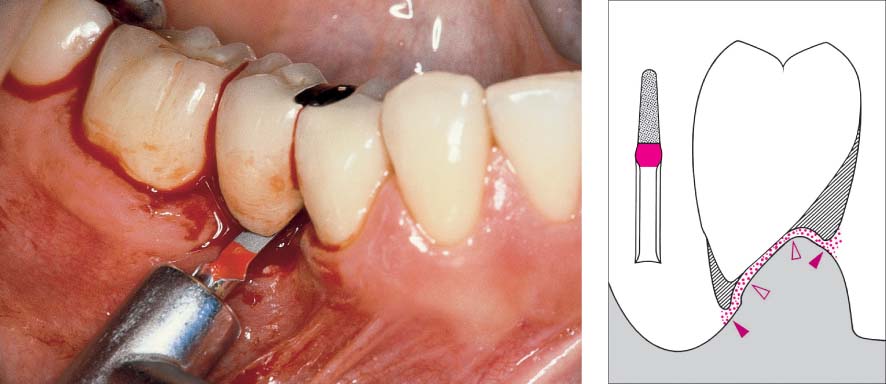

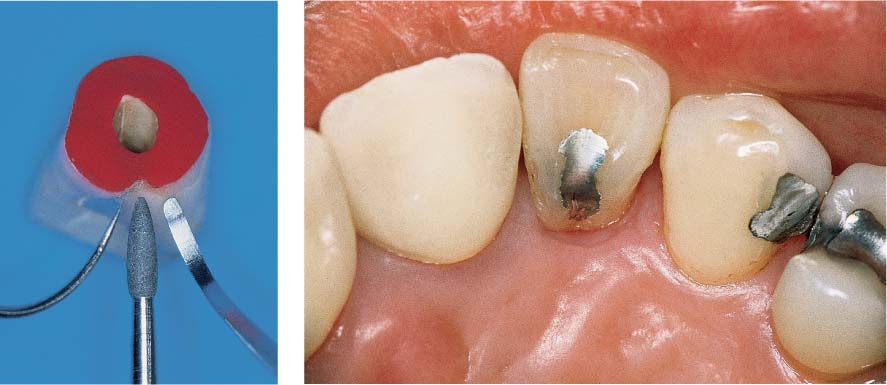

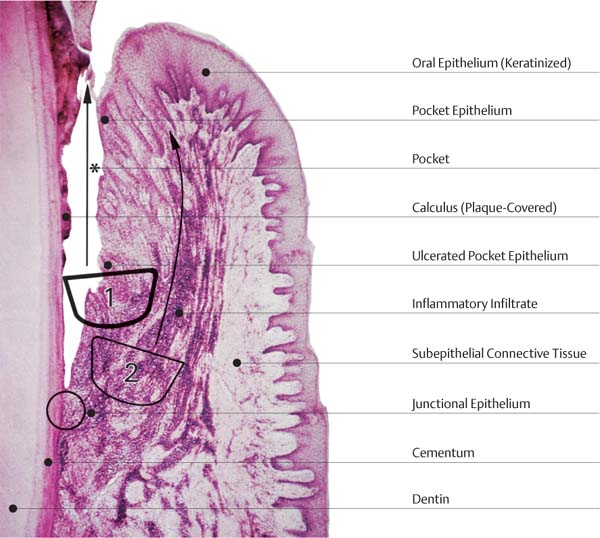

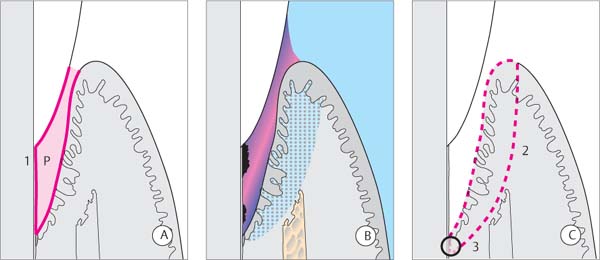

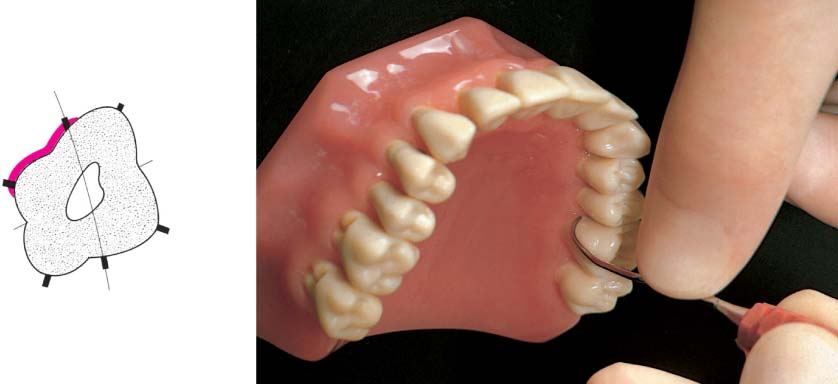

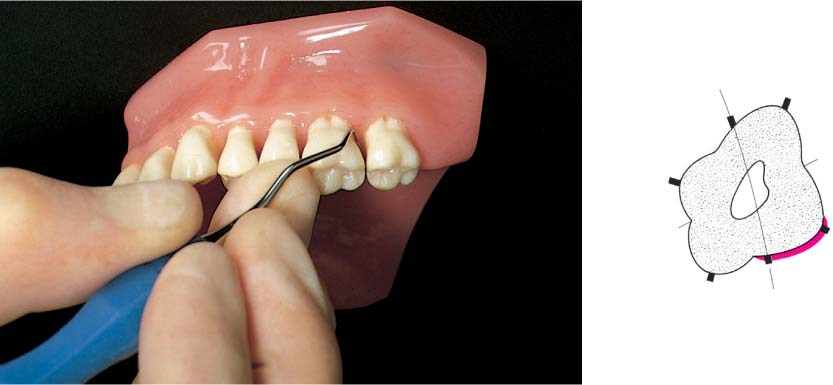

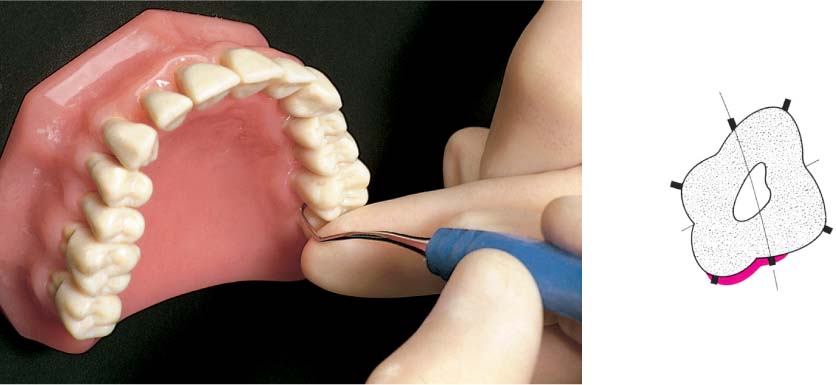

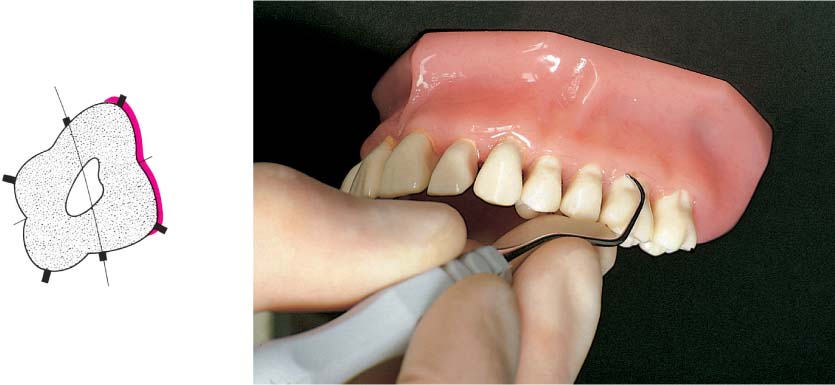

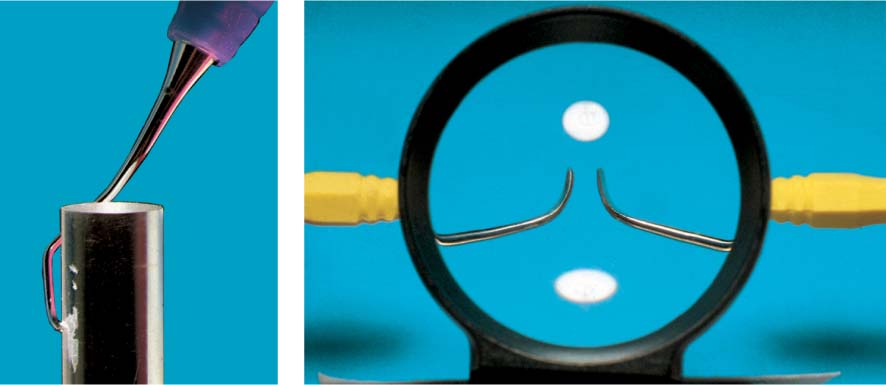

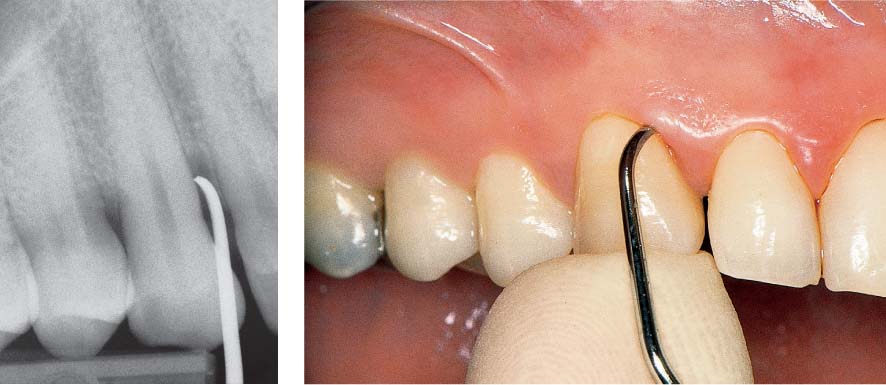

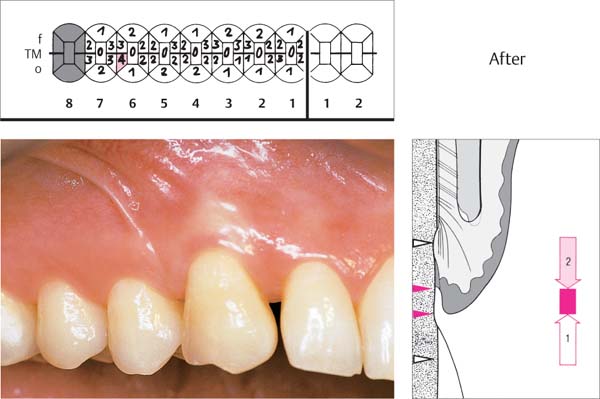

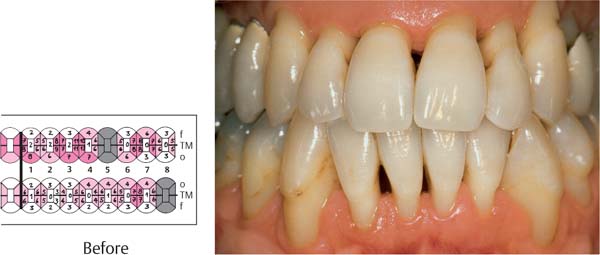

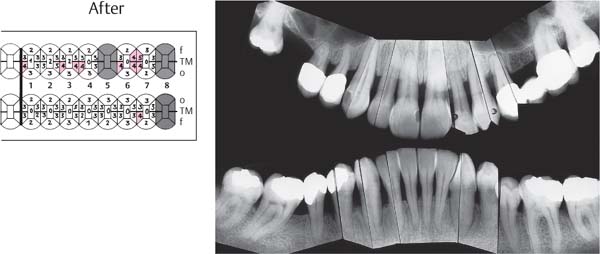

445 Irregular Base of a Periodontal Pocket in an Actual Case—Mesial View

The left central incisor exhibits a very deep pocket on its mesial aspect. The junctional epithelium that persists at the base of the pocket is marked in red. Its course is irregular and at one location is even “undercut” in the apical region. Toward the palatal aspect (left in the SEM) intact periodontal structures can still be observed.

In the center of the picture, the wall of the pocket represented by the bacteria-coated root surface is visible. The difficulty for mechanical therapy becomes clear: On the one hand the bottom of the pocket must be achieved, and on the other hand any remaining soft tissue attachment must not be destroyed.

At the sites labeled A, B and C, the structures depicted below (Fig. 446) were observed.

Left: Radiograph. Tooth 21 was extracted. Its mesial root surface is depicted in the SEM (right).

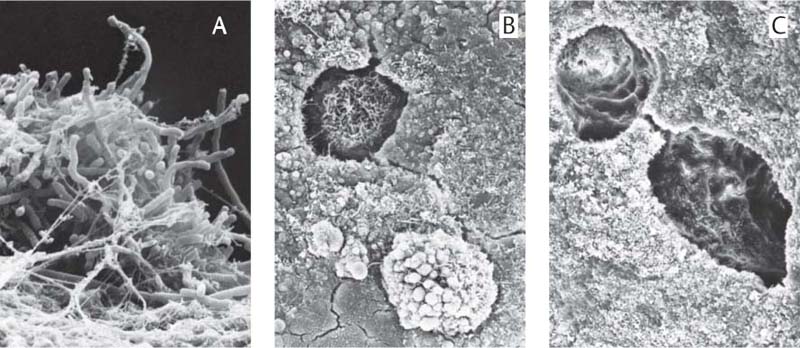

446 Root Surface in the Area of the Pocket

|

A |

Adherent Plaque/Biofilm Upon the root surface one observes a thick layer of adherent plaque. |

|

B |

Lacuna Filled with Bacteria |

|

C |

Empty Lacuna on the Root Surface |

SEM courtesy H. Schroeder

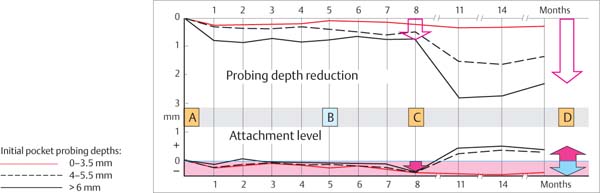

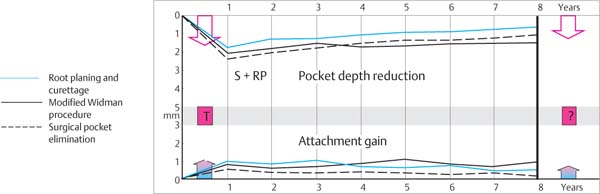

Periodontitis—Therapeutic Goals, Therapeutic Outcomes

The first goal of periodontal therapy is the complete healing of the inflammatory condition; the next goal is the regeneration of all lost periodontal structures.

Unfortunately, such total success is only seldom achieved. The enormous amount of new knowledge that has emanated from basic and clinical research, however, targets all of us in this direction. But our long-standing “gold standard” of therapy—namely closed and open tooth and root cleaning—will have to be enhanced by measures to restore defects, such as implanting bone and bone replacement materials, the GTR technique, as well as the use of matrix proteins and growth factors in the near future.

Even though the goal of complete periodontal regeneration has not yet been achieved, we can speak of partial success when applying the success criteria that are valid today. The terms “success” or “failure” and the magnitude of “partial” success following periodontitis therapy can be interpreted in many ways and depends, of course, on the initial situation, i. e., the diagnosis of periodontitis (chronic or aggressive form).

A “healing success scale” ranging from wishful thinking to achievable treatment outcomes today includes:

| **** | Complete Regeneration |

| *** | Healing of the Pockets—Repair |

| ** | Cessation of Attachment Loss |

| * | Elimination or Reduction of Inflammation |

**** Complete restoration/regeneration of all lost tissues (“4-star healing”):

This type of regeneration is only achieved (today) following successful treatment of gingivitis (without attachment loss). The treatment of periodontitis generally does not lead to total regeneration of all diseased tissues.

*** Pocket elimination via healing/repair:

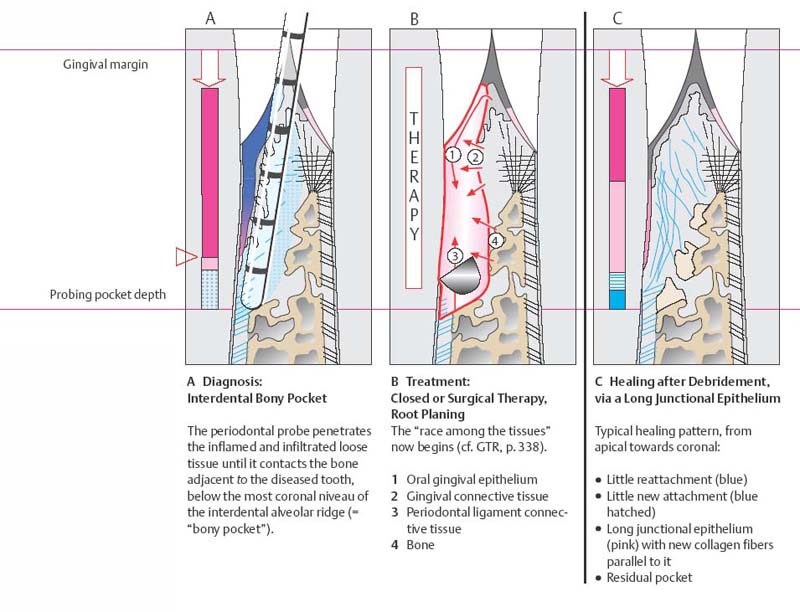

Within the marginal gingival soft tissues, this results in the formation of a long junctional epithelium and approximation of connective tissue to the root surface. In the apical regions, some regeneration of bone, cementum and periodontal ligament may occur. Following consolidation of the latter tissues, one can differentiate between “reattachment” and “new attachment.”

• “Reattachment” refers to periodontal tissues that have been partially destroyed but which are not yet infected, and which reattach to the hard structures.

• “New attachment” signifies synthesis of new periodontal tissues/structures and their attachment to a previously mechanically treated root surface. Some shrinkage of the marginal gingiva occurs and this leads to even further pocket depth reduction.

This type of “3-star healing” following periodontitis therapy can be viewed as a very favorable result.

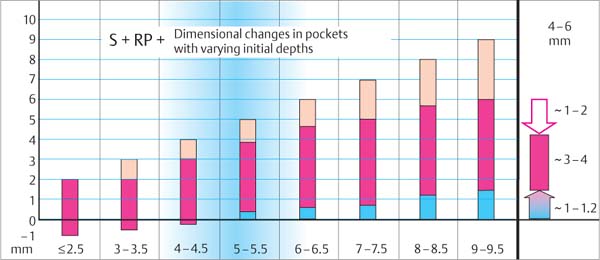

** Cessation of attachment loss at its current position:

This amounts to stopping of the progression of attachment loss in areas where pockets were in evidence, and healing by means of a long junctional epithelium. Following this type of healing, a relatively shallow and inactive residual pocket will remain. At the same time, however, the pocket depth will be reduced due to marginal gingival shrinkage, and increased tissue resiliency may lead to pocket depth reduction. In cases of advanced periodontitis, the clinician must frequently be satisfied with this type of “2-star healing”. It requires a more frequent and regular recall interval, in order to quickly assess any new inflammatory manifestations of infection in the residual pocket. Patient compliance is especially important.

* Elimination or reduction of clinically diagnosable inflammatory processes (bleeding, BOP ):

This involves a reduction of the severity of inflammation and a certain degree of tissue shrinkage, without any periodontal tissue regeneration. Residual 4–5 mm pockets remain, but they are inactive and “dry.” This “1-star healing” must be viewed as a partial success, but the situation can descend into a failure if the residual pocket becomes re-infected and if further attachment loss occurs.

The maintenance of this type of “partial success” is only possible over the long term if the patient’s compliance is good and the recall interval is short.

In addition to these primary treatment goals of periodontal pocket therapy, additional improvements in the gingivoperiodontal structures are strived for:

|

• Improvement of gingival contour and possibly also bony architecture to render plaque control easier • Optimization of the functional and esthetic situations via surgical procedures—gingivoplasty, covering recessions, alveolar crest remodelling etc. • Functional therapy, selective occlusal adjustment: Improvement of function, morphology and esthetics • Stabilization of mobile teeth (function; temporary or permanent splinting, p. 471) • Replacement of missing teeth and restoration of morphologically defective teeth; alveolar ridge augmentation |

Periodontal Wound Healing

Repair → Reattachment → „New Attachment“ → Regeneration →Prevention

Periodontal wound healing follows the well-acknowledged biological principles (Clark 1996, Fig. 447), but it is also the “most complex healing process” in the human body (McCulloch 1993): The cells of five or more tissue types—epithelium, gingival and periodontal connective tissue, bone, root cementum—are essentially asked to create a new connection to the nonvascular and nonvital hard tissue of the root surface. Healing of the periodontal wound is also rendered more complex because it must occur in an open system, permanently contaminated and under a significant “bacterial load.” It is therefore not surprising that the healing results following all types of periodontal pocket therapy can be quite variable.

In contrast, the osseointegration of a titanium implant (p. 511) is, biologically speaking, child’s play, involving only ankylotic connection to the bone. In the case of periodontal healing, ankylosis represents a failure (root resorption)!

The most basic requirement for successful periodontal treatment is a clean, biofilm-free, decontaminated root surface. In most cases, this leads to connective tissue repair, a long junctional epithelium and usually residual pockets. Ever-more successful regenerative treatment methods must be developed to insure optimal healing results.

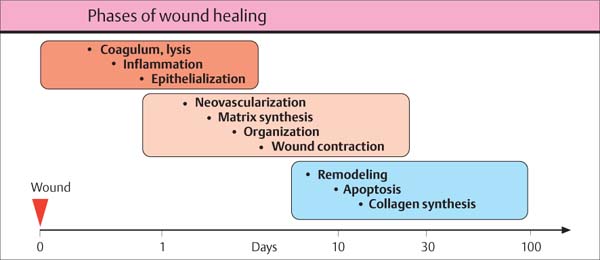

447 Principal Stages of Wound Healing

The three overlapping stages will be described. Because their temporal course is influenced by a diversity of factors, each of these stages may vary considerably in length:

• Stage of inflammation

Short duration (orange)

• Stage of proliferation

Medium duration (beige)

• Stage of maturation

Long duration (blue)

Adapted from R. Clark 1996

Regeneration of the Periodontal Defect

In addition to elimination of the tissue-destroying inflammation, true regeneration of lost tissues is one of the most important future topics in periodontology. Bony defects are filled today using autogenous or bone replacement materials; biomechanical substances (barrier membranes; GTR, p. 338) prevent the downgrowth of epithelial tissue. Thereafter, signal molecules (differentiation factors, growth factors etc.) steer migration and differentiation of pluripotent stem cells, guided by artificial or natural structures (“tissue engineering”), matrix formation and the formation of new tissue (Lynch et al. 1999).

Great progress has been made in tissue augmentation and defect filling, soon to become a standard procedure, but the more difficult task is to achieve “Regeneratio ad integrum,” namely a completely functional connection between the augmented soft tissues and especially the alveolar bone to the once infected and morphologically altered root surface (new periodontal ligament).

In all experiments to date, the formation of new cementum was only rarely identified histologically as acellular, extrinsic-fiber cementum, but more often as cellular cementum. Many authors have referred to this material as “bone-like,” which does not provide a stable connection to the root dentin.

Wound Healing and Regeneration—Possibilities

The paradigms of periodontitis therapy have changed markedly in the past two decades, due primarily to a veritable flood of new knowledge from medical specialties (McCulloch 1993, McGuire 1996, TenCate 1997, Wikesjö & Selvig 1999, Cho & Garant 2000).

New insights into the guidance and feedback mechanisms of cellular function now permit us to influence the healing processes (Bartold & Narayanan 1998, Christgau 2001, Hägewald 2002). As a result of advances in cell biology, we can better interpret the behavior of the tissues (Amar & Chung 1994, Selvig & Wikesjö 1999). For example:

• The bone-inducing capacity of demineralized bone matrix (proteins such as BMP; Jepsen 1996, Jepsen & Terheyden 2000; p. 351).

• Concepts of conditioning the nonvascular root surface (acids, Emdogain; Selvig et al. 1988, Trombelli et al. 1995, Hammarström 1997, Blomlöf et al. 2000)

• The “bioacceptability” of a formerly LPS-saturated root surface following detoxification

• The concept of tissue “compartments”; this lead to the GTR technique (p. 338), because cells colonize the surface according to the principle of “first come—first served” (Fig. 448B)

• The systemically-modulated, complex and overall active local network of growth factors and differentiation factors, signal molecules and adhesion molecules (Marx et al. 1998, Anitua 2001, Kübler & Würzler 2002)

• The existence of pluripotent stem and precursor cells within the blood stream and in the perivascular tissues.

Despite these enticing new developments and theories, periodontitis therapy today is guided by a strict anti-infectious, anti-microbial concept (Slots et al. 1999), with protocols for the individual treatment techniques. But still lacking are guidelines for the immediate postoperative period, that is during the first phase of healing, for wound care, immobilization and pharmacomechanical plaque control of the healing wound. Stabilization, especially the stabilization of the coagulum, is one of the most important measures. Stabilization mechanisms (adhesins etc.; Somerman et al. 1987, MacNeil & Somerman 1999, Somerman 2001) on the conditioned root surface prevent the downgrowth of epithelium and enhance the secure stabilization of the fibrin matrix. This serves as a natural guidance mechanism for the immigration of factor-guided future tissue cells during the second phase of wound healing.

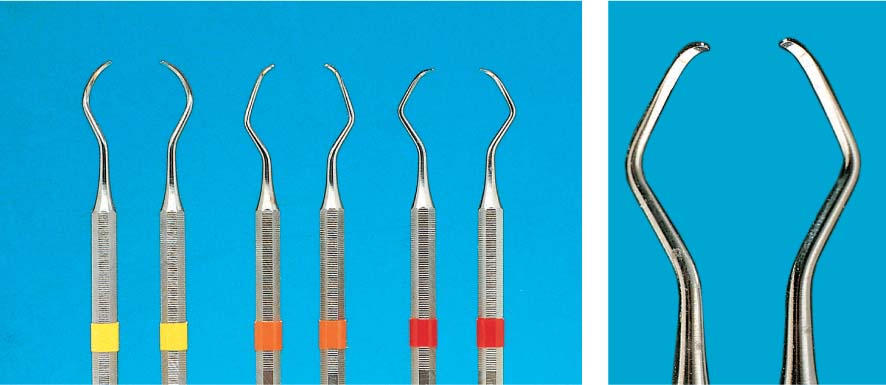

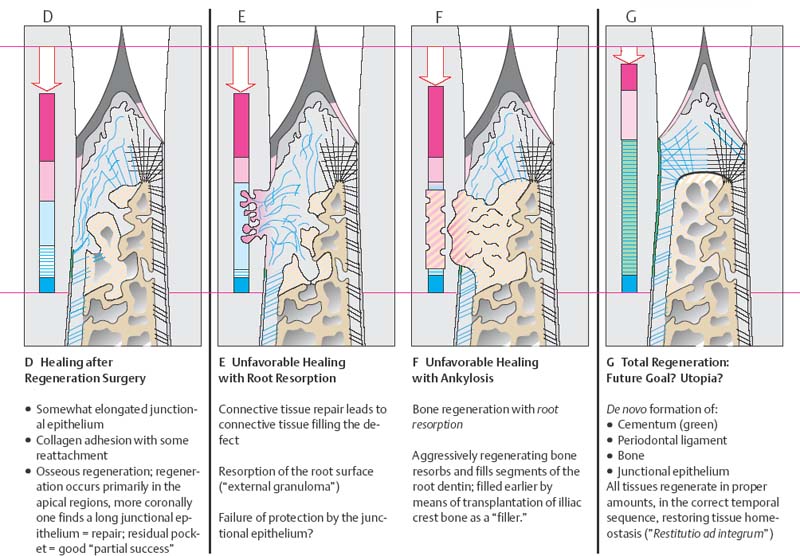

448 Possibilities for Periodontal Wound Healing

Adapted from H. Schroeder

Depicted are diagnosis (A), treatment (B) and possible therapeutic results (C—G; post-therapeutic healing) for the periodontal intraalveolar defect on the tooth shown on the left side of each illustration.

Note: The periodontal tissues of the tooth on the right side of the illustration are healthy.

448 Further Possibilities for Healing, D–G

Periodontal Wound Healing—Definitions

Histologic studies of wound healing have clarified whether and to what extent healing of the gingival and periodontal attachment apparatus is possible in the form of re-attachment or regeneration (Schroeder 1983, Polson 1986, Karring 1988). One differentiates among:

|

• Epithelium • Epithelial regeneration |

re-attachment? “new attachment” |

|

• Connective tissue • Connective tissue regeneration |

re-attachment “new attachment” |

Histologic Terminology

Regeneration—“Restitutio ad integrum”

Complete regeneration of form and function: Gingiva with junctional epithelium and gingival connective tissue; periodontium with cementum, periodontal ligament, bone.

Repair

Restoration of the continuity in the wound or defect area, without regeneration of the originally intact tissues’ form and function: e.g., long junctional epithelial attachment.

“New attachment”

New connection of connective tissue with the formerly pathologically exposed root surface, i. e., formation of new cementum with inserted periodontal ligament fibers (also, formation of new bone with Sharpey’s fibers embedded).

Re-attachment

Re-attachment is the re-establishment of the bond between connective tissue and the remaining vital tissue components on the root surface, e.g., cementum and remnants of the periodontal ligament (usually in the deepest areas of the pocket; “dark blue” in Fig. 448).

Note: Epithelial re-attachment does not occur. Epithelium is always established by new cells from the basal cell layer.

Alveolar Bone—“bone fill”

Filling a periodontal osseous defect does not provide evidence for complete periodontal regeneration (including newly formed cementum). This can only be demonstrated histologically (Listgarten 1986).

Clinical Terminology

For precise definitions of probing depth, clinical attachment level etc., see “Diagnosis” (p. 165).

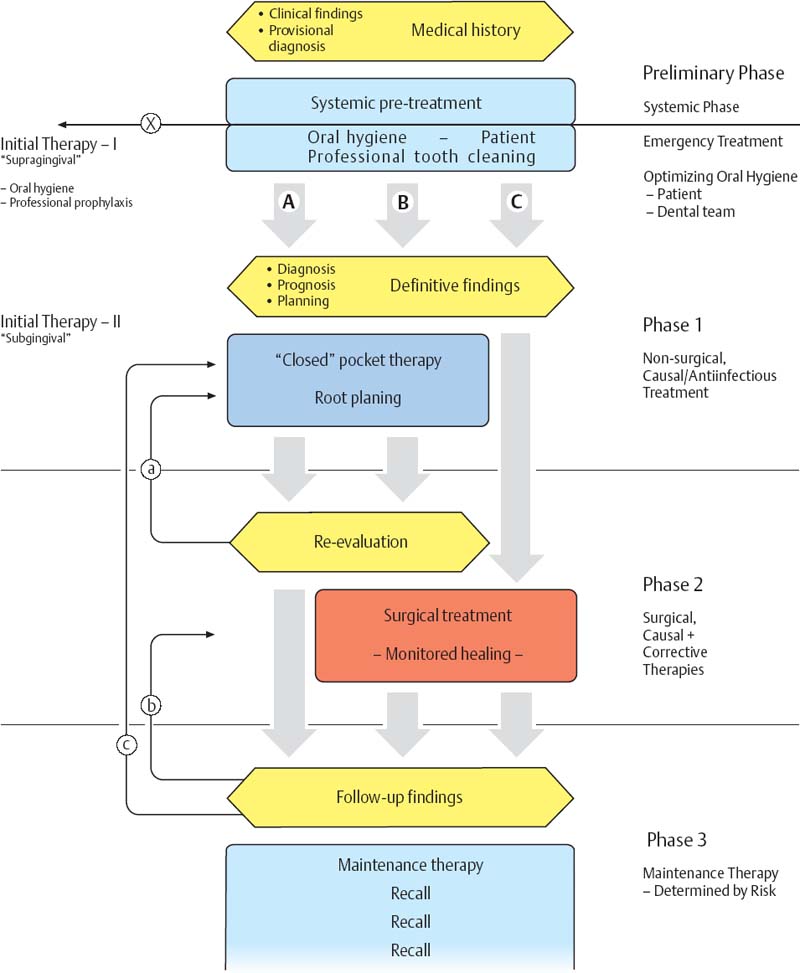

Treatment Planning—Sequence of Treatment

In principle, the course of periodontitis therapy is similar for all forms of the disease (p. 209), and is administered in stages or phases of varying duration, depending upon the extent and severity of the disease.

However the details of individual therapy may be dramatically different. These details are dependent upon the type of disease, the patient’s own desires, patient age, financial circumstances and, not least, the preference of the individual clinician! It is well known that “many roads lead to Rome”!

Pre-phase—Systemic Health, Oral Hygiene

“Phase 0” consists primarily of identifying the patient’s systemic health (general medical history, p. 167; readiness for treatment, p. 212), as well as a comprehensive data collection, the establishment of a provisional diagnosis and a case presentation (current status, necessary treatment). During Phase 0, any emergency treatment is also rendered.

The establishment of optimum oral hygiene and securing the patient’s willing compliance are extremely important for subsequent planning and the long-term result.

Professional supragingival plaque and calculus removal, the removal of iatrogenic irritants and plaque-retentive niches, as well as patient instruction in simple yet effective plaque-control will quickly improve the intraoral situation. This will convince and motivate the cooperative patient toward further and definitive participation in the comprehensive treatment program.

It must not be left unsaid that, despite optimum information and instruction, some periodontitis patients refuse “comprehensive treatment.” Such refusal must be clearly noted in the patient chart.

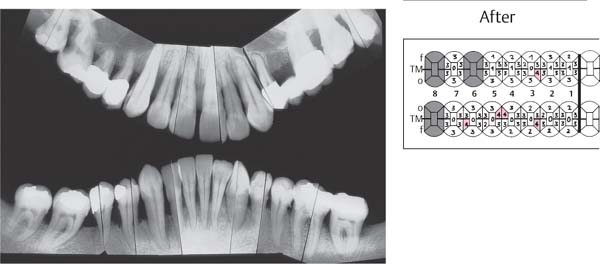

Phase 1—Causal, Antimicrobial, Anti-infectious

During this treatment phase, the findings, diagnosis and prognosis are verified. During the pre-phase, oral hygiene by the patient and the practitioner will have led to reductions in plaque and inflammation, therefore also to reduction of tissue swelling; it is reasonable to now establish a definitive diagnosis (and prognosis) based upon the important clinical findings (probing depths, attachment loss), and to formulate the definitive treatment plan.

While all of the pre-phase procedures are carried out with all patients, during Phase 1 the treatment modalities can differ. In some cases, closed root planing, with or without the concurrent use of medicaments (p. 287) may be performed, while in other cases the treatment moves directly into surgery (Phase 2).

In mild cases, above all with chronic periodontitis, closed therapy is frequently sufficient if the patient’s compliance is good.

In more severe cases it may be indicated to move into surgical-corrective therapy immediately after an intensive pre-phase.

In most cases, however, open therapy will follow closed therapy: As a consequence, in such cases fewer sites (in fewer sextants) will have to be treated surgically. The resultant tissue loss (papillae, marginal gingiva) will be less post-operatively.

Whether the case is treated solely closed (A), solely open (C), or initially closed and subsequently open (B; p. 209) depends not only upon the pathomorphologic situation, but also upon the practice structure. If the dentist works with a competent dental hygienist, the hygienist will generally perform the entire closed phase of therapy (p. 454).

Phase 2—Surgical, Corrective

Following Phase 1 therapy that includes closed, subgingival root debridement, a reevaluation must always be performed. If the treatment result is not satisfactory, individual root surfaces may again be treated with closed therapy (a). If deep pockets persist and if root fusion, grooves, furcation involvement etc. are present, these must be surgically addressed.

If the goal is to correct periodontal defects, following the pre-phase, surgical-corrective procedures are indicated. Tissue shrinkage should be avoided at all costs so that the surgical site will be optimally covered with gingival tissue following eventual application of restorative materials and/or membranes.

Most important is that the healing after surgical therapy must be continuously and professionally monitored, i. e., the operated area must be maintained supragingivally plaque-free as much as possible.

Phase 3—Preventive, Anti-infectious, “Life Long”

After conclusion of active periodontitis therapy—regardless of the type of treatment—check-up findings are collected 2–3 months later. If the therapy is deemed to be successful, the patient should be started on a regular recall (organized maintenance therapy; p. 449).

However, if individual sites exhibit problems (residual pockets, bleeding), the sites must be re-treated either closed (c) or surgically (b).

In such situations, the use of topical slow-release medicaments may be indicated (p. 293).

450 Course of Therapy—Three Possibilities: A, B, C

General Course of Therapy—Individual Planning

In the preceding pages the basic treatment planning and the course of therapy for patients with gingivitis and/or periodontitis were presented. In general, such treatment is performed according to the “phase” plan (phases of therapy; pp. 208–9).

Treatment, healing times and “pauses” for consideration of the patient and his/her oral hygiene will differ dramatically. Nevertheless, following each and every phase of treatment, a re-evaluation of the case must be performed: The treatment result and the planned further procedures must be reconsidered, and adapted as necessary to the new situation.

Causal therapy—Traditional Clinical Course

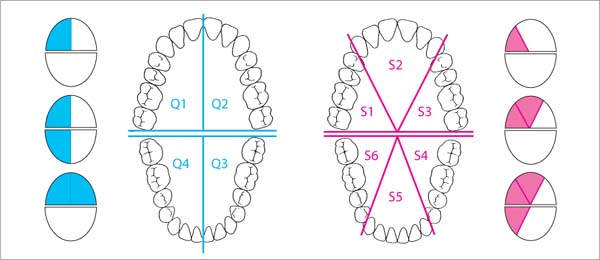

Phase 1 therapy consists of the exquisitely careful debridement of subgingival root surfaces in all periodontal pockets. For decades, this procedure has been performed quadrant-by-quadrant (Badersten et al. 1981, 1984; p. 280). The interval between individual appointments normally is one or two weeks. The quadrant scaling immediately follows the so-called “hygiene phase,” during which the patient is educated and trained to perform adequate plaque control at home.

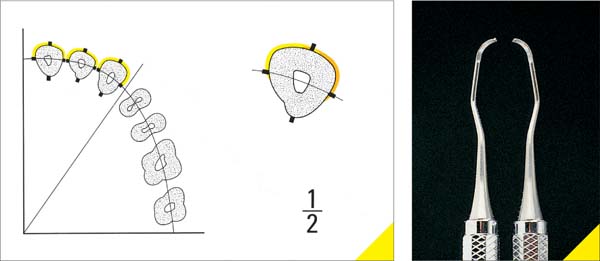

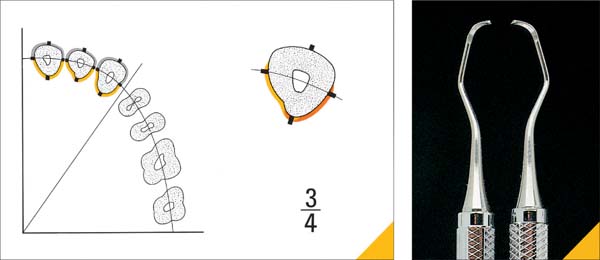

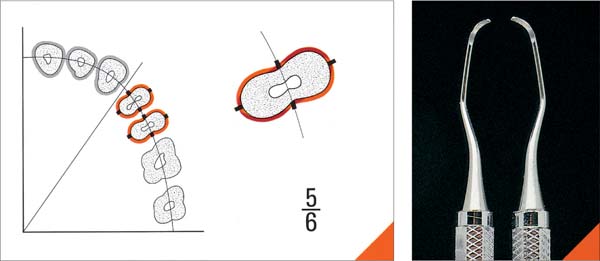

451 Quadrants—Sextants

Traditional mechanical/instrumental pocket treatment is usually performed at separate appointments for quadrants (Q1–Q4) or sextants (S1–S6); in mild cases, the left and right arch segments can be treated at one appointment.

The time required for each appointment will be determined by the severity of the case; appointments for such Phase 1 therapy are usually scheduled at 1–2 week intervals.

Causal Therapy—“Full mouth therapy” (FMT)

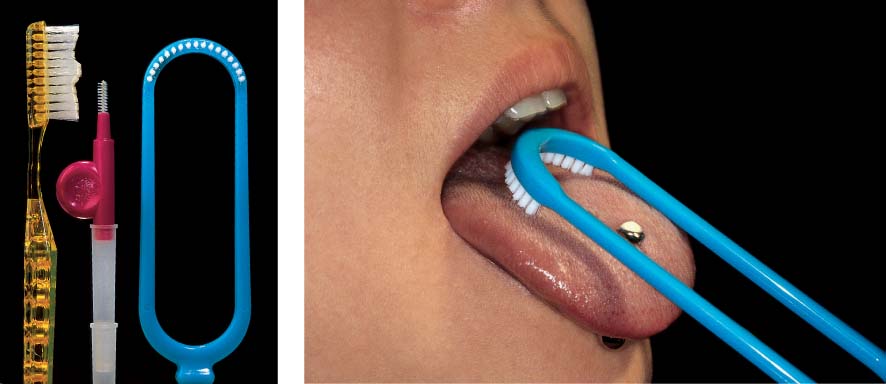

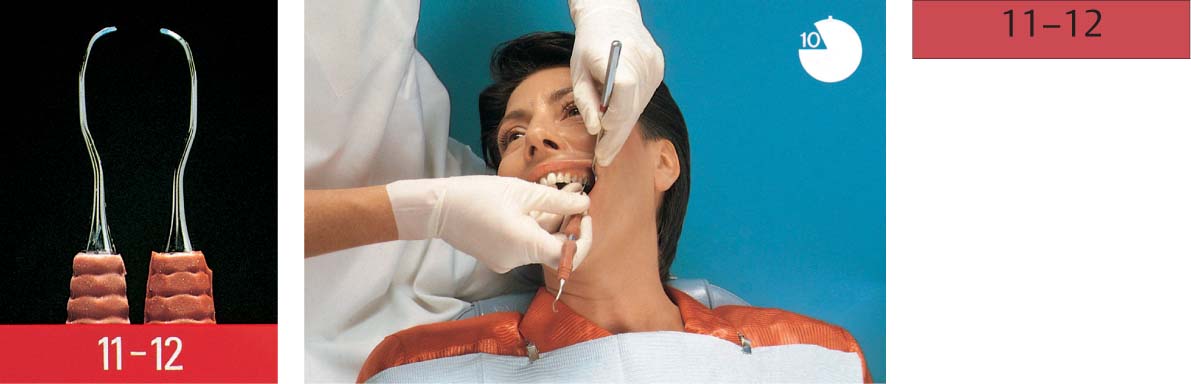

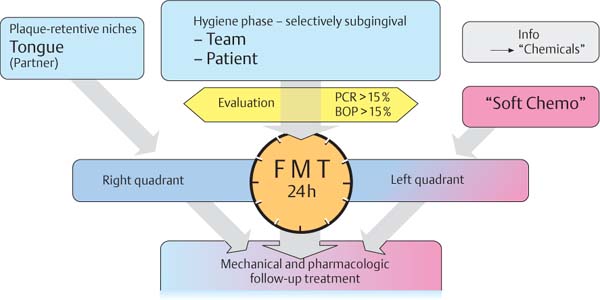

FMT represents an effort to synthesize all new knowledge from recent years. FMT is a consequential, anti-infectious approach, comprised of the following: Initial therapy includes an extended, systematic anti-microbial treatment, initially involving only supragingival pretreatment of the dentition (mechanical) and all oral niches (above all, the tongue). Only after achieving the prescribed clinical condition (p. 287), subgingival debridement (mechanically and with use of topical medicaments) is performed in the shortest possible time; in “extreme cases,” within a 24-hour period. This procedure is appreciated by most patients!

During this short-term but intensive treatment, disinfection agents such as chlorhexidine (CHX; p. 235), betadine or even oxidizing NaOCl (“bleach”) are used to rinse the mouth and the individual pockets. The goal is to prohibit re-colonization and re-infection of even shallow pockets (p. 256). Because significantly better results have been achieved using this type of closed periodontitis therapy (p. 285), in contrast to the traditional “quadrant-by-quadrant” technique, it is very likely that the FMT method will become more widespread. The necessity for surgical intervention may be reduced and the comprehensive treatment of even advanced cases may become financially more feasible

452 “Full Mouth Therapy—FMT”, “Full Mouth Disinfection—FDIS”

This new type of treatment using closed therapy is performed in the shortest possible time, preferably in only two appointments, e.g., for the left and the right sides.

Intensive pretreatment and optimum oral hygiene usually eliminate shallow pockets so that only the few remaining deeper pockets must be treated, using anesthesia (FMT, p. 281).

Systemic Pre-phase

• Systemic problems

• Systemic risks

The purpose of the systemic pre-phase is to protect both the patient and the clinician by ascertaining any general systemic risks associated with the patient.

It is critically important that infectious, above all viral diseases (Herpes, Hepatitis B and C, HIV infection) be detected and/or diagnosed: Every patient may harbor such diseases! It is therefore necessary to employ the usual hygiene measures for all dental examinations and treatments, e.g., gloves, mask and protective eyewear.

Individuals with severe systemic diseases (see ASA Classification, p. 212) can seldom be treated periodontally under the rubric “comprehensive therapy.” Usually these patients can only be treated with limited “emergency” measures, and with the participation of the patient’s physician.

Special precautionary measures are indicated with patients who suffer from multiple maladies, and most particularly with patients who are susceptible to the life-threatening danger of infectious endocarditis (Reichart & Philipsen 1999).

With non-life-threatening diseases, dental therapy should be planned in collaboration with the physician or internist, who may prescribe appropriate medications (polypharmacy); these should be checked for possible drug interactions with other agents prescribed by the dentist, as well as the possibility of undesired adverse effects (cf., gingival hyperplasia; p. 12).

Thanks to modern medicine, many of our patients lead the normal life of a healthy person. The possibility of injuring such patients during dental treatment must be ruled out (allergies, anticoagulants, hypertension, hypercholesterolemia).

Genetic and hereditary risks must be assessed, and decisions made concerning the individual patient’s treatability or non-treatability (uncontrolled Diabetes mellitus; smokers).

This chapter presents the following discussions:

|

• The patient—ASA classification • Cardiovascular diseases—“blood thinning” • Bacteremia—prevention of infectious endocarditis • Endocarditis prevention—antibiotics • Diabetes mellitus—risk factor for periodontitis • For the smoking risk factor—information, tobacco cessation program |

Evaluation—Can the Patient be Safely Treated?

Before initiating any dental treatment, the relevant medical history provided by a “new” patient must be carefully checked, regardless of whether comprehensive therapy is anticipated or only an emergency procedure. Of particular importance are serious diseases or conditions, such as:

• Cardiovascular diseases

• Pulmonary diseases

• Renal diseases

• Endocrine diseases

• Compromised immune response

• Psychological/psychiatric conditions

Acute situations should be thoroughly discussed before treatment; these include allergies, anaphylactic reactions, but also patient fear of the treatment or even fear of the injection needle.

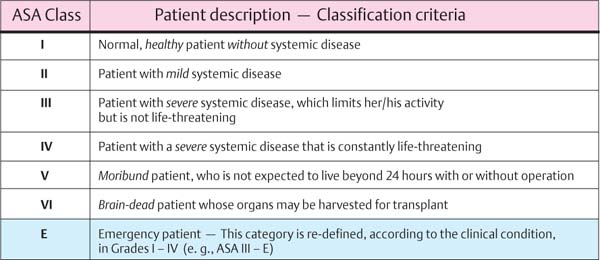

The dental team must be systematically prepared for emergency situations. Corresponding checklists, supplies and devices must be at hand (emergency kit, materials for cardio-pulmonary resuscitation, and perhaps even a defibrillator). The classification by the American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) helps to establish the physical status of a diseased patient (ASA Classes I–VI; Fig. 453)

453 ASA Classification of Patients—Health Status

Normally, only patients in Classes I and II are treated in the private dental practice, and in rare cases Class III. In the latter case, active collaboration and cooperation with the patient’s treating physician is highly recommended.

Medical Risk Factor—“Blood Thinning”

Patients with cardiac and circulatory diseases (post-myocardial infarction, Angina pectoris etc.) or other conditions (e.g., post-surgical condition, dialysis patients, thrombosis prophylaxis etc.) usually take anticoagulants:

|

• Short-term therapy: |

Heparin |

|

• Long-term prophylaxis: |

Aspirin derivatives |

|

• Long-term therapy: |

Cumarin derivatives (e.g., Warfarin) |

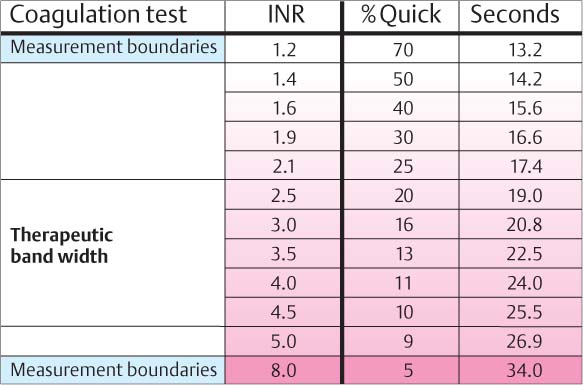

In order to avoid life-threatening hemorrhage, the patient’s actual “Quick-time” (Cumarin) must be assessed. A Quick value of ≥ 30% usually does not affect dental or oral surgical procedures, but values between 15 and 25 % demand consultation with the treating physician.

• The effect of blood-thinning medications is enhanced by non-steroidal anti-inflammatory agents such as salicylate, mefenamine acids, tetracycline, metronidazol and sulfonamides (Scully & Wolff 2002).

• Their effects will be reduced by barbiturates, glucocorticoids, alcohol, and foodstuffs with a high vitamin-K content.

The antidote for Cumarin is vitamin K; there is no antidote for the rapidly metabolized heparin. If necessary the patient may stop taking this medication for a short period of time.

454 Coagulation—Tests of Blood Thinning

Because the results vary greatly, the old Quick-Test will be abandoned in the near future. It will be replaced by the INR blood thinning test (“International normalized ratio”) which provides constant values and ease of use by the patient!

Therapeutic bandwidth: INR values of 2.5–4.5, depending upon the risk status of the patient.

Bacteremia—Endocarditis Prophylaxis

Transient bacteremia is a natural, daily occurring situation (chewing, tooth brushing). In healthy persons, oral bacteria that enter the blood stream are efficiently eliminated by the host defense system.

Infectious endocarditis (IE) is a life-threatening disease, an infection of hemodynamically exposed defects (plaque formation on heart valves), usually elicited by oral microorganisms (streptococci).

Depending upon the virulence of the etiologic microbe and the resistance of the patient, various forms of IE can be differentiated (Müller 2001):

• Acute, infectious forms

Sepsis, fever, endocardial destruction; death in less than 6 weeks

• Acute/Subacute forms

Intermediate forms, often elicited by enterococci

• Subacute forms

Slight fever; if untreated, death between 6 weeks and 3 months

• Chronic forms

Symptoms the same as subacute; death in more than 3 months

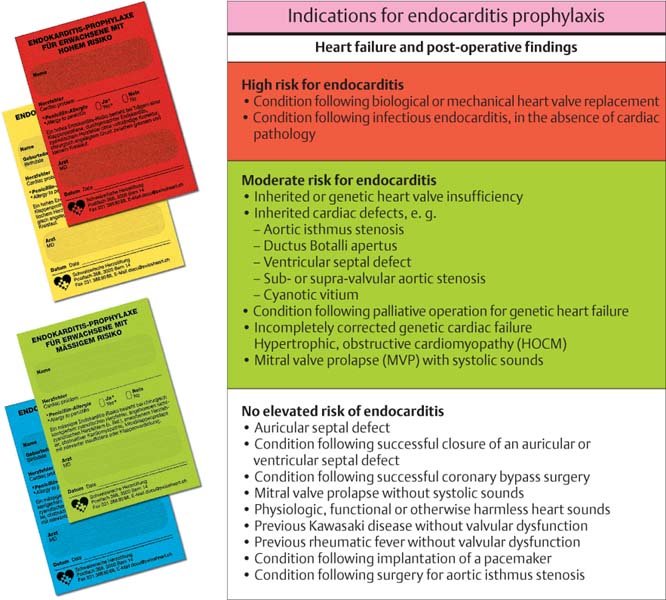

455 Heart Diseases and Cardiac Defects—Indications for Endocarditis Prophylaxis

Within the new wording of the prophylaxis program from the AHA (American Heart Association; Dajani et al. 1997) the risk structure of the heart was newly categorized in three groups:

• High risk (red)

• Moderate risk (green)

• Non-elevated risk

Of importance for the dentist is that the presence of a cardiac pacemaker is not an indication for antibiotic, pre-treatment prophylaxis (but care must be exercised when electronic instruments such as ultrasonic scalers are employed).

Left: Individual patient cards from the Swiss Heart Foundation, listing guidelines and dosages for endocarditis prophylaxis.

• High risk

|

red |

→ adults |

|

yellow |

→ children |

• Moderate risk

|

green |

→ adult |

|

blue |

→ children |

Infectious endocarditis (IE)

A wide variety of microorganisms such as bacteria, mycoplasm, fungi, rickettsia or chlamydia can elicit IE if they enter the bloodstream due to trauma or tissue manipulation. Regions of the cardiovascular system that experience slow blood circulation or a high level of turbulence are particularly susceptible to infections.

The most frequent source of microorganisms that elicit IE is the oral cavity. The primary pathogens are gram-positive streptococci (viridans type), especially Streptococcus sanguis.

In addition to S. aureus and S. epidermis, more and more often one also observes gram-negative bacteria from the oral cavity and the upper respiratory tract that elicit IE; for example, A. actinomycetemcomitans, Hemophilus ssp., Cardiobacterium ssp., Eikenella corrodens, Kingella ssp., Capnocytophaga, Neisseria ssp.

For the protection of IE-endangered patients, bacteriocidal antibiotics of the “penicillin type” (p. 214) are recommended. As early as 1983, J. Slots and others suggested that IE prophylaxis could also include metronidazol (see Medicaments, p. 287).

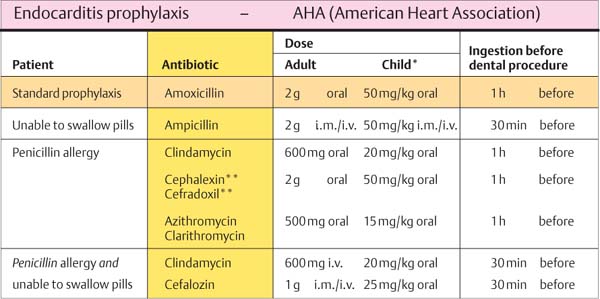

Endocarditis Prophylaxis with Antibiotics

According to new guidelines from AHA (Dajani et al. 1997), the prophylactic dose of standard antibiotic (Amoxicillin) was reduced to 2 grams; in addition, no follow-up dose is now recommended; not all other Heart Associations agree.

It is comforting for dentists to know that most of the, albeit rare, cases of endocarditis do not result from invasive, surgical treatments! Nevertheless: Oral, especially periodontal surgical procedures take place in a highly contaminated area. Expansive and/or deep surgical procedures have almost always been performed with antibiotic prophylaxis. For this reason, recommendations concerning which dental procedures require endocarditis prophylaxis were welcomed (Newman & Winkelhoff 2001).

456 Endocarditis Prophylaxis

The standard antibiotic for IE prophylaxis is Amoxicillin.

For patients who are allergic to this bacteriocidal broad spectrum penicillin, and/or those who cannot swallow pills, some alternatives are provided.

* Maximum children’s dose, depending upon body weight; do not exceed the adult dose!

** Cephalosporine and penicillin must not be used with Type 1 hypersensitivity!

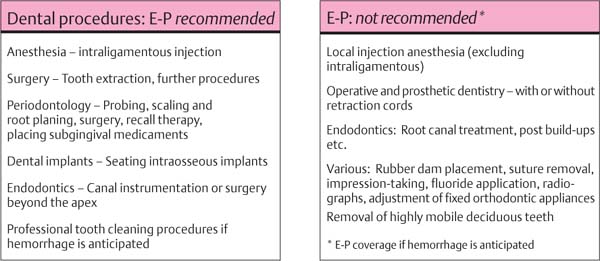

Dental Procedures Carrying the Risk of Bacteremia

Bacteriemia will occur following all dental procedures that elicit bleeding. The endangered patient must be premedicated with the “one-shot” prophylaxis (AHA) before:

• Tooth extraction, surgical tooth extraction

• Root tip resection

• Suture removal, dressing change

• Calculus removal

• Intraligamentous anesthesia

• Periodontal probing (Fig. 457 left).

Bacteriemias of varying frequency and severity also occur after chewing hard foodstuffs (15–50 %), during tooth brushing (5–25 %), or during oral irrigation (25–40 %; according to Neu 1994).

The percentage and number anaerobic species were approximately twice as high in patients with poor oral hygiene and advanced periodontal diseases in comparison to patients with good oral hygiene. Bacteriemia occurs in these patients also, but patients at risk for endocarditis should not abandon mechanical oral hygiene; rather, they should rinse 30 minutes beforehand with chlorhexidine.

457 Dental Procedures Requiring Antibiotic Endocarditis Prophylaxis (E-P)

For single procedures the prophylaxis measures suggested above are sufficient.

If, however, an extended phase of treatment is planned, a longer-lasting (adjunctive) medication must be considered, combined with an intensive intraoral antiseptic regimen (p. 287).

Diabetes mellitus (DM)—Risk Factor for Periodontitis

A new classification for Diabetes mellitus was presented in 1997 (WHO; American Diabetes Association):

|

• Diabetes mellitus Type 1 (formerly IDDM) • Diabetes mellitus Type 2 (formerly NIDDM) • Other diabetes with known etiologies • Gestation Diabetes (pregnancy Diabetes) |

Untreated, all forms of the disease are similar in the elevated blood sugar level and alterations in carbohydrate and lipid metabolism (DGP 2002/Risk factors).

• The less common DM Type 1 occurs due to the autoimmune-elicited destruction of insulin-producing β-cells of the pancreas. The consequence is acute insulin deficiency.

• DM Type 2 diseases are not primarily insulin-dependent (over eating, sedentary lifestyle!); Type 2 Diabetes today has achieved epidemic proportions. The number of cases is increasing rapidly, and is estimated at 150,000,000 cases worldwide.

DM today is frequently one component of the “metabolic syndrome,” together with obesity, elevated blood lipid and high blood pressure (“deadly quartet”; syndrome X).

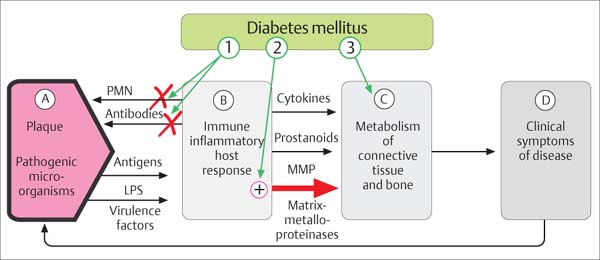

458 Risk Factor—DM

The effects of persistent hyperglycemia are many. Various target cells react inappropriately to glycosylated lipids and proteins (AGE, “advanced glycated end-products”), mediated via the specific receptor RAGE.

1 Defective PMNs and antibodies

2 Macrophages with enhanced catabolic mechanisms

3 Altered extracellular matrix

Adapted from R. Page 1998

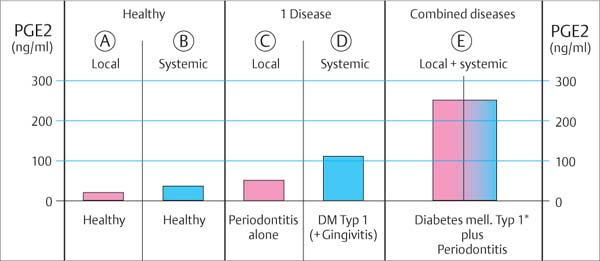

459 Differences in Host Response in Health, Type 1 Diabetes and Periodontitis Patients

The levels of the strong pro-inflammatory mediator prostaglandin E2 (PGE2; p. 49) differ massively.

In patients with Diabetes and periodontitis (E), an extreme overproduction of PGE2 is observed, which complicates the disease picture.

Adapted from G. Salvi et al. 1998

Periodontitis Therapy for Diabetes Patients

An important first step is the meticulous anti-infectious initial therapy and the establishment of an optimum blood sugar level (internist). Persistence or progression of periodontitis can lead to elevated insulin resistance, and can increase the diabetic consequences:

• Retinopathy (vascular damage, p. 133; blindness)

• Nephropathy (renal high pressure as a consequence)

• Neuropathy

• Angiopathy (atherosclerosis—peripheral, heart, brain)

• Disturbances of wound healing

• Severity of periodontitis (the “sixth complication”)

Periodontitis and Diabetes mellitus exhibit numerous reciprocal effects. Both can therefore be referred to as reciprocal risk factors. Chronic infection of the periodontal pocket (gram-negative microorganisms, lipopolysaccharide) elicit within the altered glycosylating cells of a diabetic an increase in excessive reactions of the defense cells, which is characterized by release of large amounts of pro-inflammatory, catabolic mediators (Grossi & Genco 1998). Diabetes and periodontitis should therefore be treated simultaneously, where necessary employing systemic antibiotic support (doxycycline) (Miller et al. 1992; Westfelt et al. 1996; Tervonen & Karjalainen 1997).

Smoking—An Alterable Risk Factor

Because of its numerous negative consequences for general systemic health, regular heavy smoking is one of the most dangerous addictions. It is also the most significant alterable risk factor for periodontal diseases.

In addition to nicotine, tobacco smoke contains up to 4,000 toxic, cancer-causing components. Therefore, a tumor-screening examination should be performed on all patients who smoke, including meticulous inspection of the entire oral cavity (Reichart 2002, Reichart & Philipsen 1999).

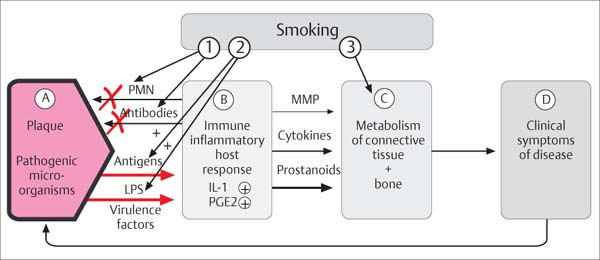

Pathogenesis: Nicotine and its by-products compromise the host response to infection, including within the periodontal tissues (Müller 2001):

• Reduced chemotaxis and phagocytosis by PMNs

• Reduced synthesis of immunoglobulins (IgG2)

• Stimulation of pro-inflammatory cytokines and additional mediators (IL-2, IL-6, PGE2)

• Elevated numbers of anaerobes in the subgingival region, including T. forsythensis, P. gingivalis, and also members of the “orange complex” (Haffajee & Socransky 2001)

• Damage to fibroblasts (gingival and periodontal)

460 Risk Factor—Smoking

Where and how does tobacco smoking influence the pathogenesis of periodontal diseases?

1 Activity of PMNs, reduced secretion of immunoglobulins (IgG2)

2 Enhancement of subgingival anaerobic microorganisms

3 Influence on gingival, periodontal and osseous metabolism

Adapted from R. Page & K. Kornman 1997

461 Smoking Cessation Using Nicotine Substitutes

“Nicorette” products; from left to right:

| • Microtabs: Sublingual tablets • Inhaler: Cartridges within a cigarette mouthpiece • Transdermal patch: For 16 hours (5, 10 and 15 mg) • Nicorette chewing gum |

The Nicorette products are available in differing concentrations and in some instances different taste formulations.

Smoking Cessation

The dental team sees the patient in recall at least twice per year and is therefore almost predestined to accompany the tobacco cessation process. Treatment results in smokers with aggressive periodontitis and poor oral hygiene are definitively poorer, on average, than in non-smokers. Caution is the watchword before regenerative procedures, e.g., filling bony defects, whether on natural teeth or dental implants. In the face of additional risk factors (oral hygiene, Diabetes, positive IL-1 polymorphism etc.) one is wise to avoid regenerative procedures of any kind (Tonetti et al. 1995, Müller et al. 2002, Jansson et al. 2002, Machtei et al. 2003). If the smoking cessation program is to be effective, the time factor, and uncompromising patience, will play major roles. Motivational discussions about smoking cessation often follow the “five A’s”: Ask, advise, assess, assist, arrange (Ramseier 2003).

Cessation programs including the various forms of nicotine replacement substances (Fig. 461) have proven effective. Without nicotine, the medicament “Zyban” (bupropion) is effective.

Emergency Treatment

Many periodontitis patients are not aware of their disease, even though it may have been progressing over many years. Only when pain and acute inflammatory symptoms appear do such patients seek out a dentist.

Such emergency cases must be treated immediately. However, to avoid life-threatening incidents, a succinct general medical history must be taken, with particular attention to any medicines the patient may be taking (anticoagulants!) and an assessment of the necessity for infection prophylaxis (endocarditis, HIV etc.), as well as allergies and previous significant incidents.

Next, a clinical and radiographic examination should be performed for emergency patients; despite the pain, this is absolutely necessary before any treatment.

Included in the category “periodontal emergency situations and treatments” are:

|

• Initial topical medicinal and mechanical treatment for acute NUG • Treatment of acute, suppurating pockets • Opening periodontal abscesses • Immediate extraction of hopelessly mobile teeth that cannot be maintained • Acute, combined endodontic-periodontal problems • Treatment of periodontal trauma following accidents |

Acute ulcerative gingivoperiodontitis (acute NUG/NUP) is painful and progresses very rapidly. Careful instrumentation and application of topical agents generally bring relief within a few hours and a reduction of the acute situation. Caution: Ulceration may be a symptom of HIV-seropositivity (opportunistic infection).

Active suppurating pockets generally are not painful if drainage is established at the gingival margin (exception: abscess). Such pockets represent an exacerbating inflammatory process, which leads to rapid attachment loss. They must be treated immediately with application of rinsing solutions or ointments; mechanical cleansing must also be initiated.

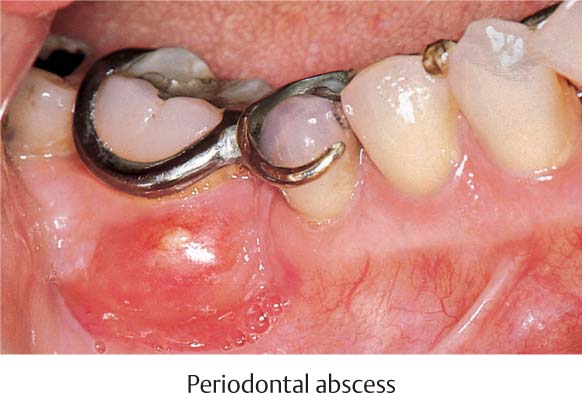

Periodontal abscesses are usually very painful. They must be drained immediately. This can usually be accomplished via probing from the gingival sulcus.

In the case of molars with deep pockets or furcation involvement, an abscess that penetrates the bone may develop subperiosteally. These cannot always be reached via the gingival margin, and must be drained by means of an incision.

Immediate extraction should be reserved for teeth that cannot be maintained or are highly mobile or which cause the patient undue discomfort. In the case of anterior teeth, for esthetic reasons, extractions should be avoided when possible, or an immediate temporary should be prepared.

Acute, endodontic/periodontal processes have a more favorable prognosis if the primary problem is of endodontic origin. The root canal should always be treated first, subsequently the pocket (pp. 445–447).

Periodontal trauma due to accident usually requires immediate splinting (following any necessary reimplantation or repositioning of the tooth).

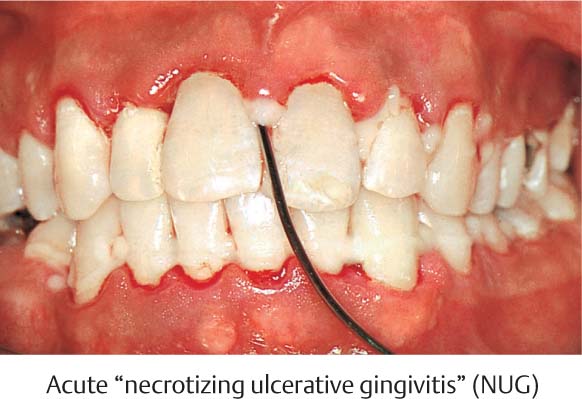

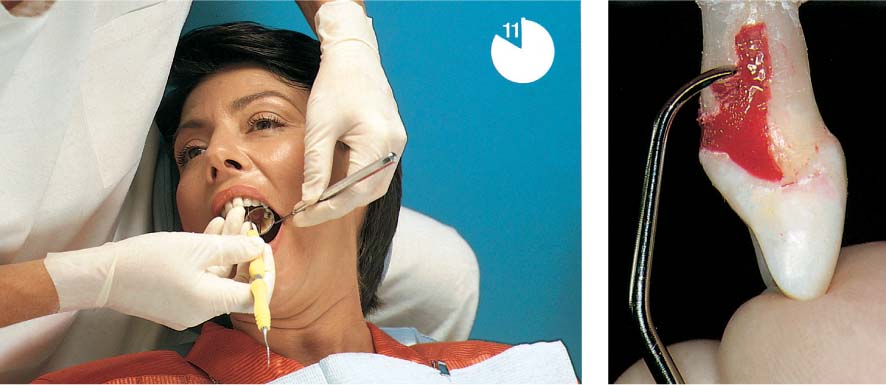

462 Emergency Situation: Acute Necrotizing Ulcerative Gingivitis (NUG)

The severe pain in the acute stage permits only a very careful peripheral attempt at cleansing. Treatment of this acute condition involved gentle debridement with 3 % hydrogen peroxide, and application of a disinfecting ointment containing anti-inflammatory and analgesic ingredients. The patient was told to rinse at home with a chlorhexidine solution.

463 After Emergency Treatment—Subacute Stage

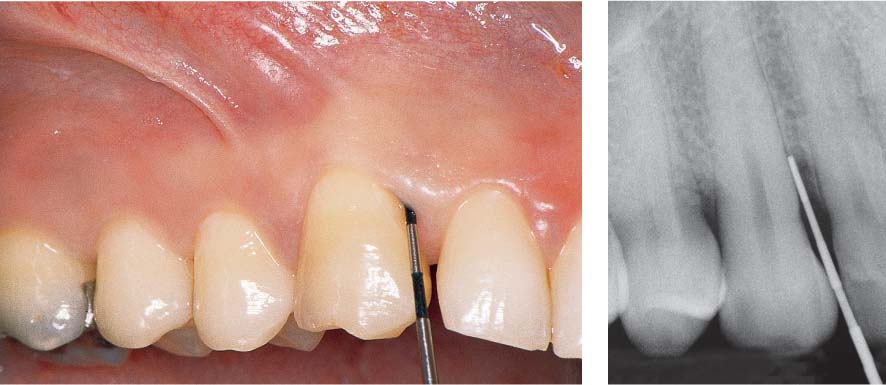

Several days after gentle topical application of the medicaments and careful mechanical debridement, the signs of active NUG—especially the pain –subsided. Treatment by means of systematic subgingival scaling can now proceed. A gingivoplasty may be indicated subsequently in the normal course of treatment.

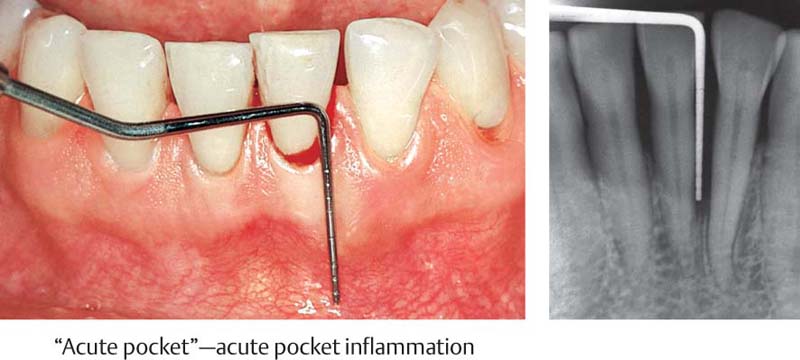

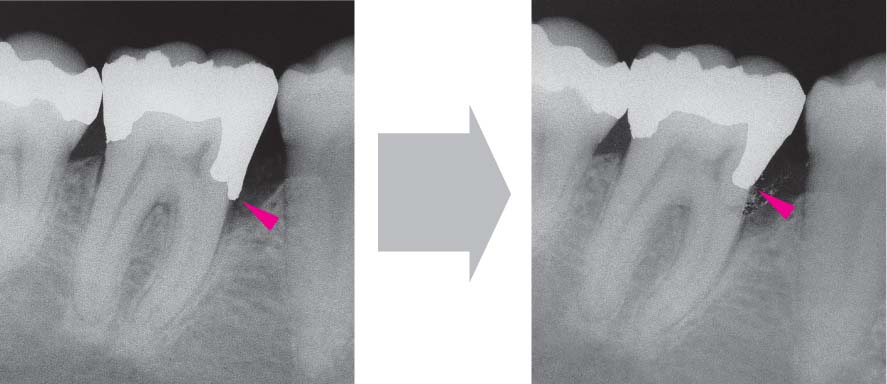

464 Emergency Situation—Localized Acute Pocket

Tooth 31 is vital and should be maintained despite the 10 mm pocket. Very little pus has formed; drainage via the gingival margin appears possible. The tooth is slightly percussion sensitive. Prior to systematic mechanical treatment, the tooth is treated on an emergency basis with topical application of a medicament, and the pocket is disinfected.

Right: Note the deep defect on the distal of tooth 31.

465 Emergency Treatment Using Local Medicament, and Follow-up

As an emergency measure the pocket was first rinsed thoroughly with chlorhexidine solution and then filled with achromycin ointment (3 %). Once the acute symptoms subside, a thorough root planing can be performed.

Right: Eight weeks after the emergency therapy, the gingiva has regained its resiliency and has shrunk somewhat. Probing depth is now only ca. 3 mm.

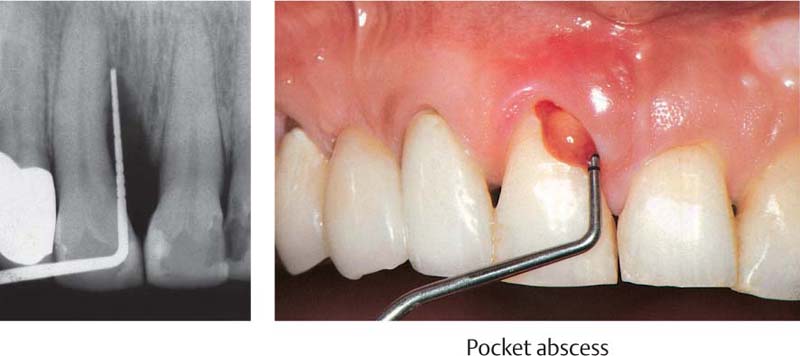

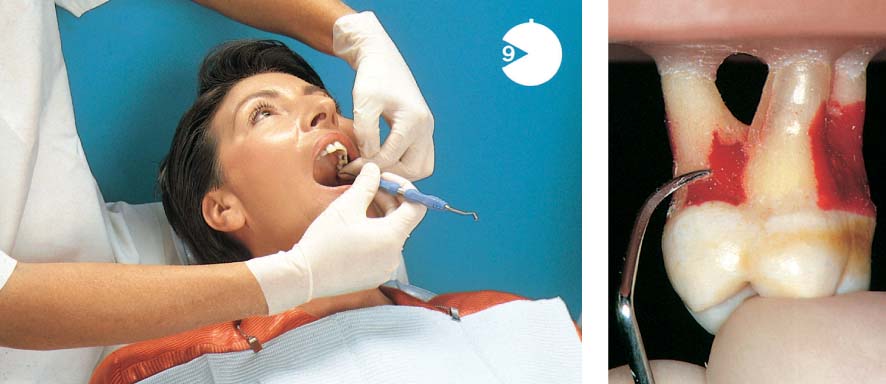

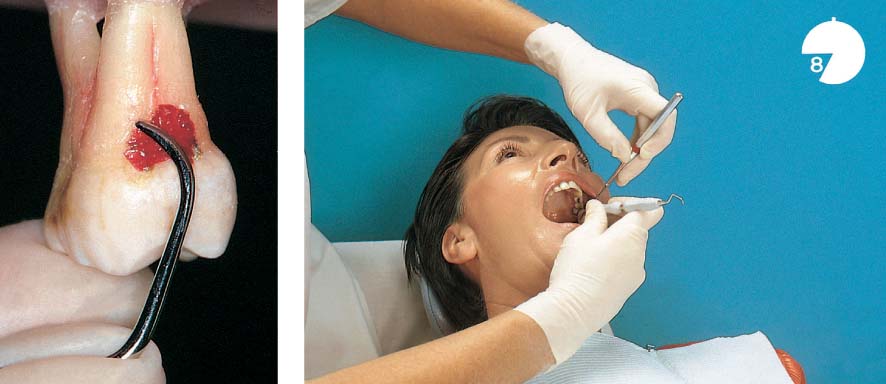

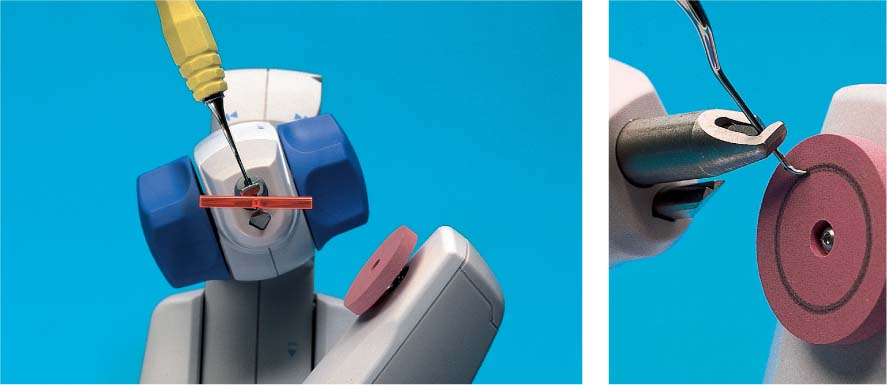

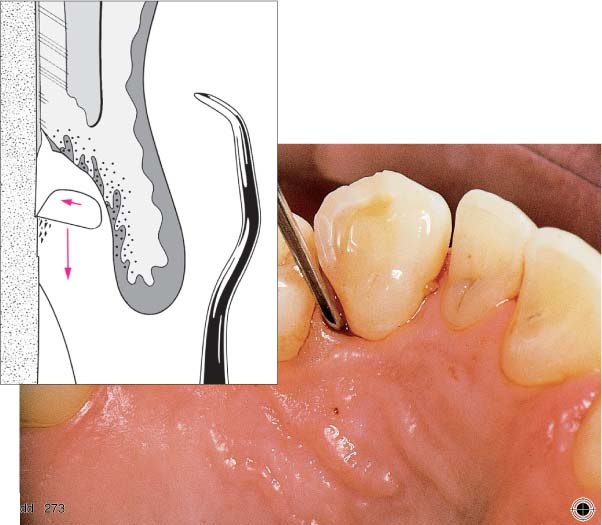

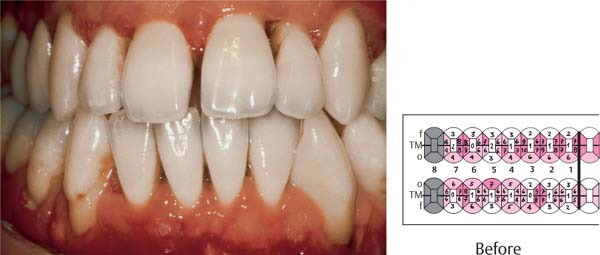

466 Emergency Situation: Pocket Abscess—Drainage after Probing From the Gingival Margin

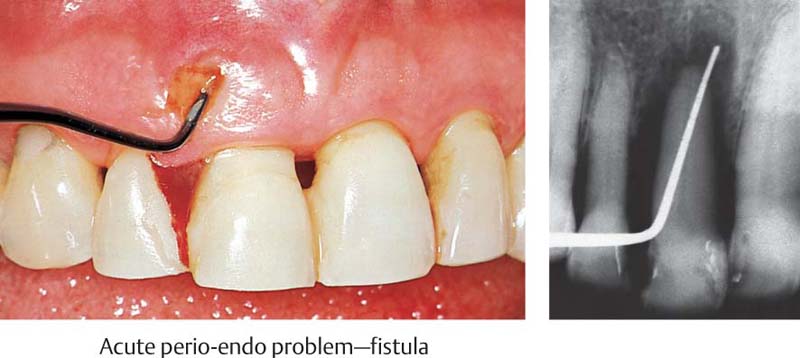

Originating from a deep pocket mesial to tooth 11, a periodontal abscess has formed. Copious pus exudes when the pocket is probed.

Left: The radiograph depicts the periodontal probe inserted to the base of the osseous defect.

467 Emergency Treatment Using Topical Medicament—Radiographic Follow-up

The abscess has opened via the gingival margin. The pocket is first thoroughly rinsed, then filled with an antibiotic-containing ointment. Once the acute symptoms have subsided, definitive therapy can be undertaken.

Left: Radiograph 6 months after definitive therapy: New bone formation is apparent.

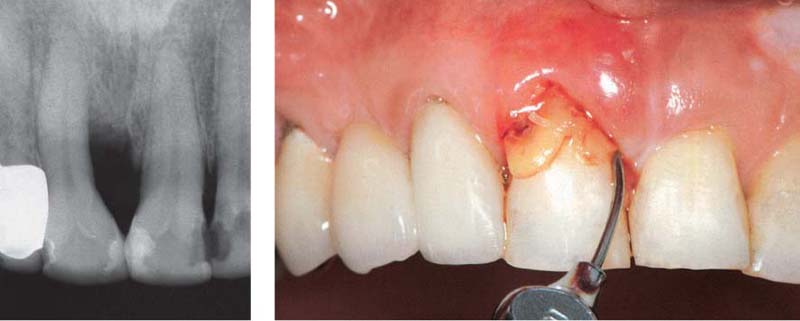

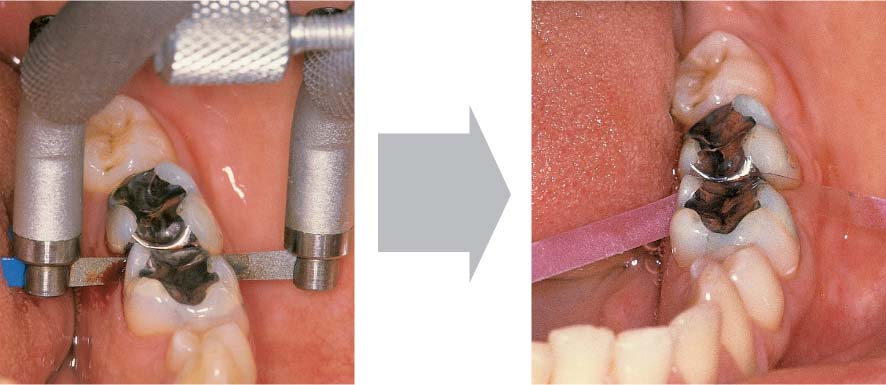

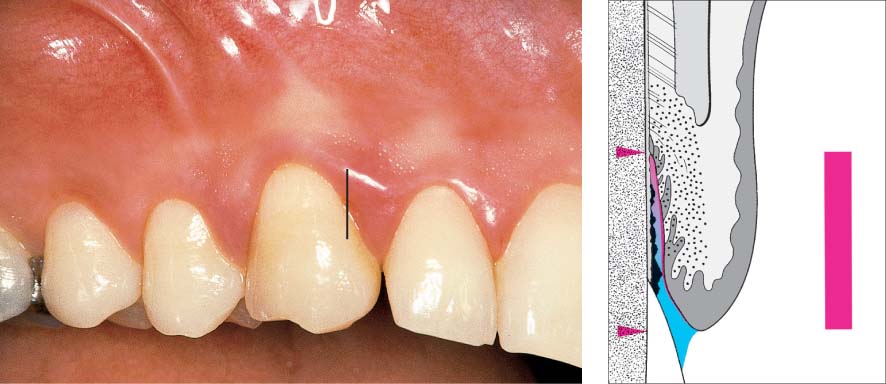

468 Emergency Situation: Periodontal Abscess Anticipates Drainage Through the Gingiva

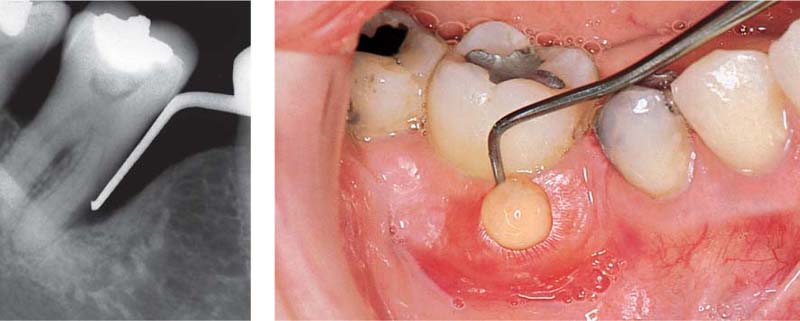

Originating from the deep, one-wall infrabony pocket mesial to the tipped but vital tooth 47, an abscess has developed. The buccal gingiva is distended as the abscess is about to penetrate through the mucosa.

Tooth 47 is an abutment for a removable partial denture that is ill-fitting, but the patient wants to retain the partial denture.

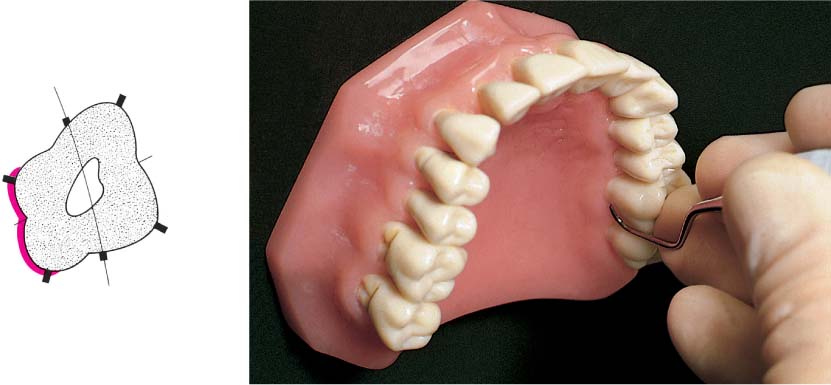

469 Abscess—Drainage

As soon as the mucosa was touched the abscess opened and copious pus exuded.

Left: In the radiograph one observes the deep mesial periodontal pocket with a hoe scaler in situ. Since the furcation appears not to be involved, it is possible to consider maintaining this tooth. The ensuing treatment included mechanical debridement and topical application of medicaments.

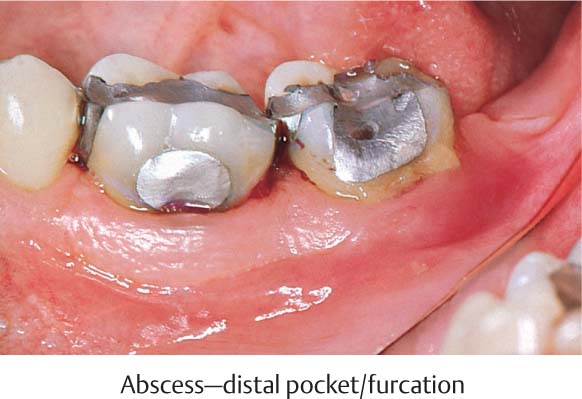

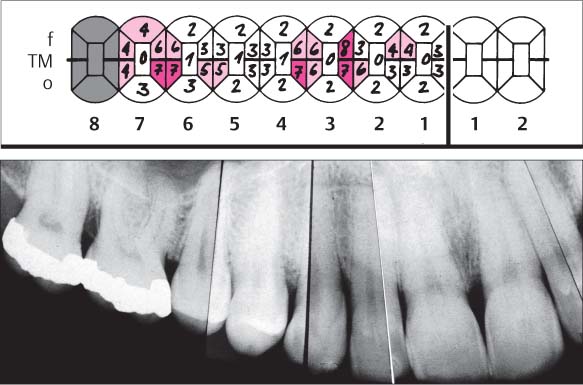

470 Emergency Situation in the Posterior Segment: Hopeless Molar (37)

Pus exudes spontaneously from the deep distal pocket and the buccal furcation of tooth 37.

The tooth is vital, highly mobile and painful to the slightest touch.

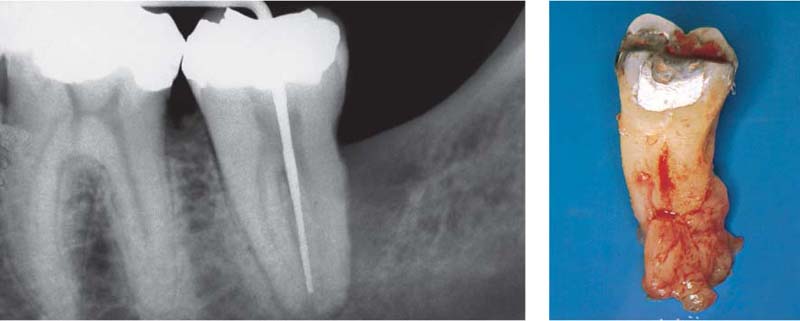

471 Radiograph of 37 Before Immediate Extraction

The periodontal probe can be inserted almost to the root apex in the deep buccal pocket. Without clinical probing, such a defect at this location would be almost impossible to detect. The shape of the furcation is very unfavorable in terms of treatment; the two roots appear to fuse apically.

Right: Highly infiltrated granulation tissue remains attached to the root after extraction.

472 Emergency Situation in the Anterior Area: Painful Tooth 11 is Hopeless—Fistula

A fistula emanating from the deep pocket has developed. The non-vital tooth is highly mobile and sensitive to percussion. This tooth cannot be saved; it was extracted immediately.

Right: The radiograph reveals that a probe can be carefully inserted far beyond the apex (endo-perio problem, p. 445).

473 Immediate Extraction—Immediate Temporary

An immediate temporary is necessary for esthetics. Following extraction the root was severed and the crown was used as a temporary. A wire and acid-etched resin secured the crown to the adjacent teeth. This type of temporary can usually be maintained until definitive reconstruction.

Right: Radiographic view of the temporary replacement consisting of the patient’s own tooth crown.

Phase 1 Therapy

Causal, Antimicrobial, Non-surgical Therapy

Primary prevention— the early prevention of disease—is initially the responsibility of parents. Using simple, non-traumatic tooth brushing methods, the small child is gently guided down the path of personal hygiene and especially oral hygiene, hopefully with the support of his/her role models: Mother, father and perhaps older siblings. It should become a habit that the results of a child’s own efforts in oral hygiene be observed, lauded and, when necessary, modified.

In healthy individuals, prophylactic measures are usually short, painless and require little time. Nevertheless, they prevent dental caries and gingival diseases!

If disease occurs over the course of time, e.g., initial gingivitis in the specialty of periodontology, a brief description of the cause (bacterial biofilm), and its professional removal, as well as renewed instruction in plaque control by the patient (tooth brushing, oral hygiene), healthy conditions can be again established—secondary prevention.

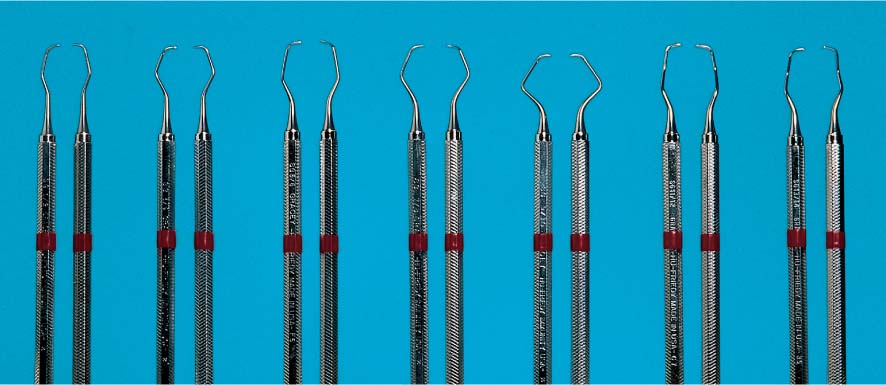

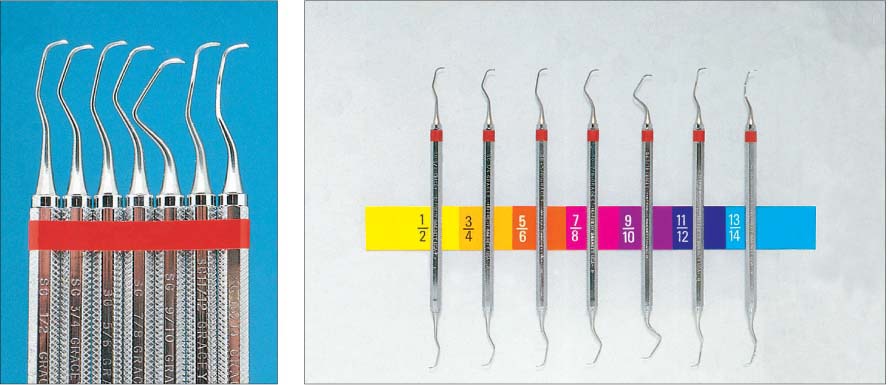

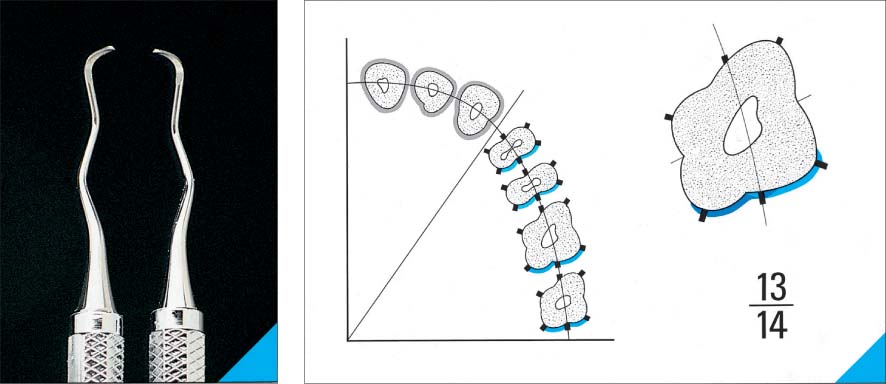

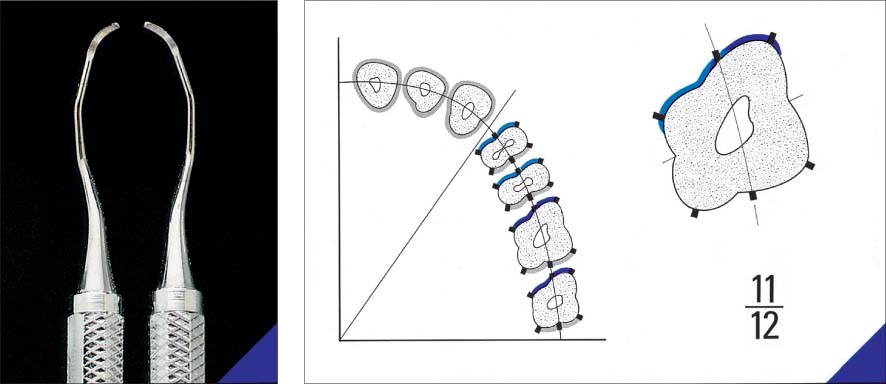

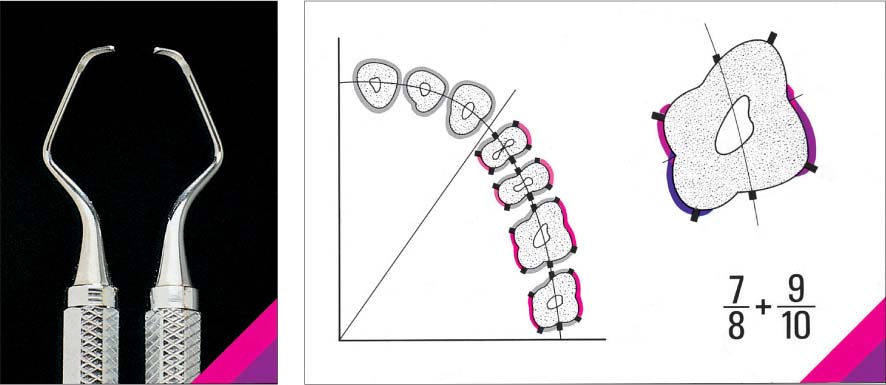

If true pockets have formed and attachment has been lost, it is necessary to intervene as early as possible for such cases of early periodontitis. Using the simple measures of closed, causal therapy (debridement, root planing) such cases can be cured. Only a few years ago, predictable treatment success was only possible in pockets of 4–6 mm; but today it is possible to achieve predictable success even in pockets of 8 mm and more with the help of new and improved procedures (“After Five” curettes, disinfectants, modified timing, and other equipment innovations).

Nevertheless, anatomical relationships such as furcation involvement, grooves, narrow bony craters, and the regeneration of tissue defects oftentimes make it necessary still today to employ a multifaceted, often complicated corrective (surgical) technique with open therapy (Phase 2 therapy/surgery; p. 295) following Phase 1 (closed, subgingival) treatments.

This chapter, “Phase 1 Therapy,” will unfold as follows:

|

• Case presentation |

– Motivation toward self-help |

|

• Initial treatment 1 |

– Oral hygiene by the patient – Creation of hygienic relationships by the dental team |

|

• Initial treatment 2 |

– Traditional closed pocket treatment – FMT—“full mouth therapy” |

Case presentation—Motivation—Information

The maintenance or reinstatement of periodontal health (freedom from inflammation, full function) is possible even in terms of esthetics assuming certain prerequisites. But this can only be accomplished through the cooperative interaction between the patient and the dentist: The patient must be interested in maintaining the health of the oral cavity, and must be interested in a proposed treatment, and must be motivated to participate (compliance).

The patient should first be informed about the causal relationships that led to the disease process. The dental team has numerous possibilities to demonstrate to the patient soft tissue alterations elicited by inflammation, and the responsible etiologic factors (Roulet & Zimmer 2003).

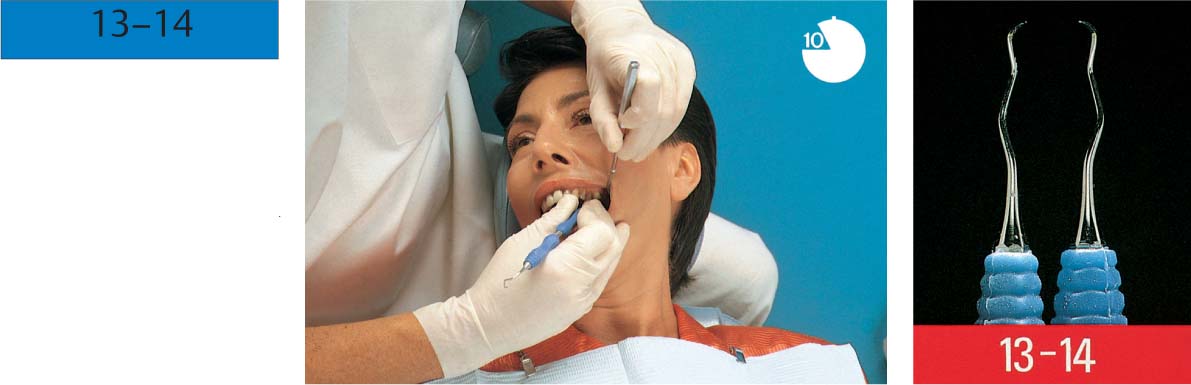

474 Motivation and Information During the Case Presentation

During the very first appointment, during the discussion of medical history and the collection of diagnostic data (here by the dental hygienist), the patient will want to be informed as much as possible about his/her oral condition.

This is an opportunity to motivate the patient and solicit compliance, because “without compliance, a good result will not be achieved.”

A primary goal of the case presentation is to convince the patient of the many possibilities for bringing the treatment to a successful conclusion.

Oral Hygiene Instruction Aids

The clinician must consider and take seriously the fact that the patient’s own case is what interests the patient most. Panoramic radiograph on the light box, easily visible clinical findings such as recession, plaque-retentive areas, bleeding on probing, gingival erythema and swelling etc. are easy to demonstrate and explain to the patient who holds a mirror.

At subsequent appointments, the interested patient can again be informed and motivated, for example through use of disclosing agents (p. 224) to visualize plaque at the gingival margin or in the interdental spaces. Dental plaque microbial “vitality” can also be used for patient motivation by means of microscopic enlargement (Plakoskope, p. 180); an inexpensive TV camera and monitor can dramatically depict plaque vitality for the patient.

Additionally, other instructional materials such as brochures, tooth models, and high-tech instruments such as digital intraoral cameras can be used to transmit to the patient the necessary information about health and disease.

It has been reported and demonstrated many times that a flood of new information often overloads or exceeds the patient’s available memory, and the patient is soon no longer capable remembering all of the details. It has therefore proven to be helpful to give the patient small but informative take-home brochures or pamphlets, to be read and studied as follow-up to the information the patient heard as he/she sat in the treatment chair.

Initial Treatment 1—Oral Hygiene by the Patient

The patient’s oral hygiene (plaque control) remains today the primary supportive pillar of periodontal prophylaxis. It also supports treatment, and has great significance for maintenance of the treatment results.

Without continuous compliance by the patient, periodontal treatment by the dentist and the dental team will be less successful and the success will be of shorter duration. Oral hygiene by the patient means, above all, reduction of the amount of plaque and pathogenic microorganisms in the oral cavity. Gingival massage with the toothbrush is of secondary importance, with perhaps some “psychological” effect.

In special indications, mechanical plaque control can be enhanced or supported for a limited period of time by topical medicaments (disinfection agents such as chlorhexidine).

This chapter will describe:

|

• Plaque disclosing agents, revealing the plaque • Manual toothbrushes • Toothbrushing techniques, systems • Electric toothbrushes • Interdental hygiene—interdental hygiene aids • Dentifrices • Chemical plaque control—CHX, additional products • Irrigators, of value? • Halitosis, bad breath—oral hygiene • Possibilities, successes and limitations of oral hygiene |

Toothbrushes of all kinds are important aids for mechanical plaque removal. They reach, however, only the facial, oral and occlusal tooth surfaces.

The initial lesions of gingivitis and periodontitis, as well as dental caries, usually occur in the interdental region. Therefore, the toothbrush must be enhanced by additional hygiene aids that can ensure cleansing of the interdental area.

There is no single oral hygiene method that is right for every patient. The type and severity of the periodontal disease, the morphological situation (crowding, spacing, gingival phenotype etc.) as well as the patient’s own manual dexterity determine the required hygiene aids and the cleaning techniques. During the course of periodontitis therapy, the techniques may have to be changed or adapted to the new morphological situation (longer teeth, open interdental spaces, exposed dentin).

The patient must be informed about his/her daily oral hygiene, its frequency, time spent and amount of force to be applied. In most cases, once per day is sufficient for a thorough and systematic plaque removal (disruption of the developing biofilm; Lang et al. 1973).

In the final analysis, though, it is not the hygiene aids, the technique or the time spent that is the determining factor, rather the result: Freedom from plaque. This parameter as well as the health of the of the gingiva (BOP) must be checked at regular intervals.

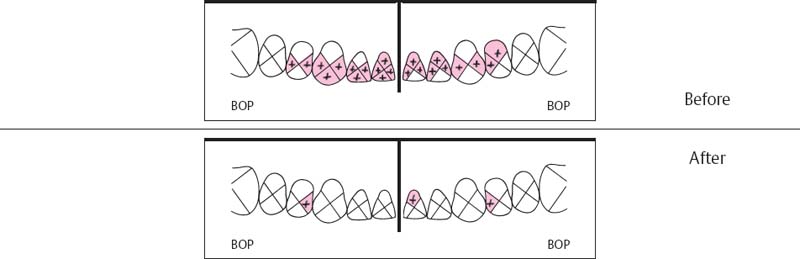

Motivation—Gingival Bleeding

Since 1980, the clinical symptom “bleeding on probing” has assumed the foreground in patient motivation, replacing plaque disclosure. The profession realized that it is not the amount or expanse of plaque or its depiction in a microscope that was most meaningful to patients, rather it was the reaction of the patient’s own tissues to the microbial irritation that held the highest motivational value.

Each person exhibits very different individual reactions to the biofilm, its constituents and especially the microbial metabolites. Thus, even with identical amounts of plaque, quite different levels of pathogenic danger may be present.

Using the PBI (Saxer & Mühlemann 1975, Mühlemann 1978) or BOP (Ainamo & Bay 1975, p. 69) the severity of gingival inflammation can be numerically portrayed. If the gingival bleeding index decreases during initial treatment (1), as depicted by repeated clinical recording of the index, this provides visible evidence of success while simultaneously giving further motivation to the patient.

Bleeding on Probing as a Motivating Factor

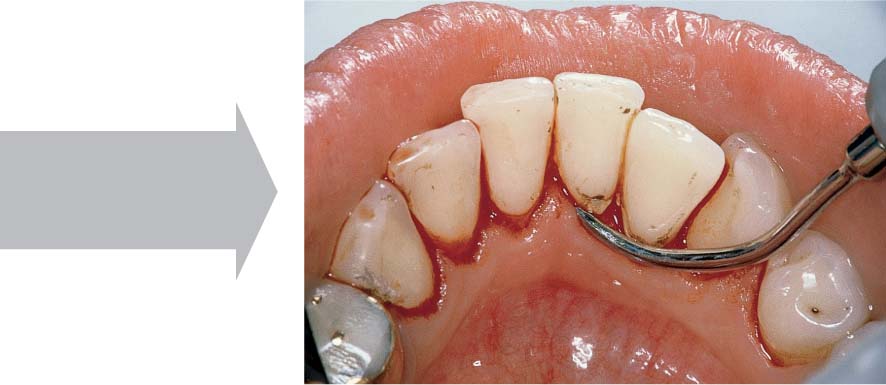

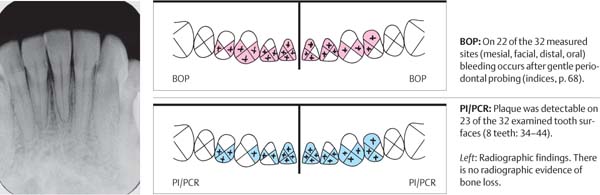

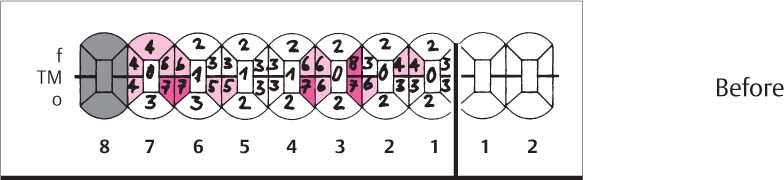

475 Initial Condition: Moderate Periodontitis

The patient can clearly see the severe hemorrhage as the clinician performs the bleeding index (PBI or BOP).

Right: As a second step, disclosing the plaque reveals the cause of the disease. The next steps include initial oral hygiene instruction and professional, supragingival prophylaxis.

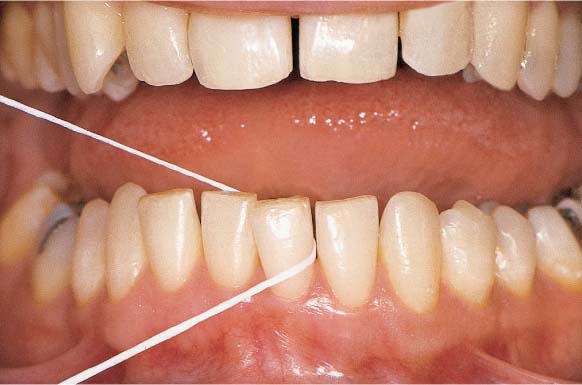

476 Clinical Situation: Two Weeks Later

Following professional prophylaxis and repeated OHI, the patient can readily see the return to health as indicated by the minimal bleeding during recording of the PBI data.

The patient is motivated by this success to further intensive cooperation and compliance.

477 Clinical View at 4 Weeks

The virtual absence of bleeding (inflammation) and the dramatic plaque reduction convinces the patient definitively of the logic of this treatment.

Right: The minimum plaque accumulations demonstrate the correlation: Less plaque = less gingivitis.

Additional oral hygiene instruction is now targeted toward those sites that are not completely plaque-free, e.g., interdental areas.

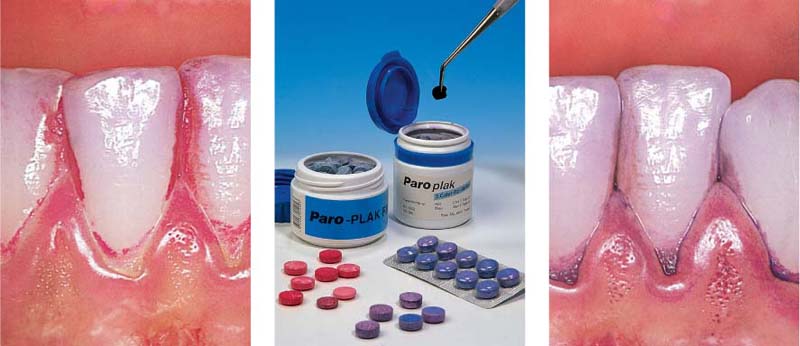

Plaque Disclosing Agents

Frequently during the case presentation, when motivation is being emphasized using the bleeding index, the patient will pose questions concerning the cause of periodontal disease. Now—right now!—is the prime time for demonstration of microbial plaque, the most important etiologic factor in gingivitis and periodontitis.

Using non-toxic food coloring agents, the adherent plaque on tooth surfaces and gingiva can be selectively stained. The patient watches in a mirror as the clearly visible plaque is revealed and then scraped off using a probe.

Patients are further impressed to hear that only 0.001 grams of plaque contain ca. 300,000,000 bacteria. The necessity and possibility for plaque removal via oral hygiene measures becomes visible to the patient, and the initial toothbrushing instruction session falls on fertile soil.

One disadvantage of plaque disclosing agents that remain in the mouth for some time can be avoided by using the Plaklite system (Fig. 480). A solution that is virtually invisible in daylight clearly reveals accumulated plaque bacteria when illuminated with blue or UV light.

478 Red and Violet Disclosing Agents

Left: Classic red staining by erythrosin. This procedure is still permitted by the FDA.

Middle: Plaque disclosing agents for the patient (tablets) and for the clinician (solutions, pellets).

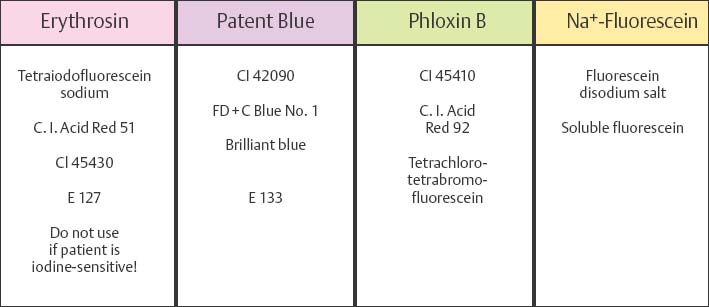

Right: Differential disclosing agents that stain “fresh” plaque light violet, and old, “mature,” plaque a darker violet color.

479 Details of Four Plaque Disclosing Agents (adapted from Roulet & Zimmer 2003)

Older, deeply-staining agents such as basic fuschsin, malachite green and other “histologic stains,” which are depicted in some illustrations in this Atlas, are no longer used in clinical practice because of their potentially injurious side effects or toxicity.

480 Fluorescent Disclosing Agents, Blue or UV Light

In normal room lighting, plaque disclosed with 0.75 % Na-fluorescein solution appears light yellow (left), but glows intensively yellow-green under blue light (right).

The disclosing products are available from Vivadent, Lactona, Clairol and Intern. Pharmaceutical Co. (IPC) and others.

A disadvantage of this technique is the requirement of a special light source or a filter mirror.

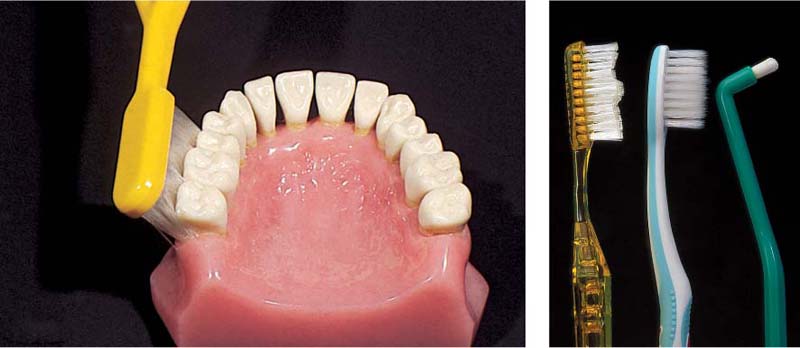

Toothbrushes

For centuries, the toothbrush has served to remove of food debris and plaque from all facial, oral and occlusal tooth surfaces. Today the toothbrush remains indispensable, but it does not provide adequate interdental hygiene. In addition, when used with excessive force it has the potential to injure even healthy gingiva.

There is no ideal toothbrush (shape, size, handle) but in periodontics more and more brushes with softer, flexible bristles have found acceptance. Rounded bristle tips are the standard today.

Worthy of consideration also is the fact that toothbrushes are always used with toothpastes (p. 234). It seems only reasonable that these two components should be “synchronized” for each individual patient (König 2002) and this must be accomplished by the dental team. This should replace the often wildly extravagant commercial claims with facts, and permit targeted recommendations for each individual patient.

481 “The Best Brush”

Patients always ask: “What’s the best toothbrush”? Who wins gold, silver or nothing?

Fact: There is no “best” brush!

For the dental team it is important to know the commercially available brushes, but more important to know the needs of the individual patient, in order to properly advise.

482 ADA Type and New Trends

New brushes and their efficacy are standardized according to ADA guidelines after in vitro testing. Clinical tests with human subjects are more costly and provide limited data. The ADA “norm” (left) is a four-row brush, multi-tufted. At right today’s trend, the Oral-B “Cross Action.”

Right: Rounded bristle tips are today’s standard.

483 Toothpaste and Toothbrush: One Goal

The role of the toothbrush is generally overvalued! Only in combination with a dentifrice is it effective; the toothbrush is really only a carrier. Its positive effects (gingival massage?) are insignificant. Its negative effects, especially with hard bristles, can be grave: Damage or injury to gingiva and mucosa can lead to gingival recession or aphthous ulcers.

The question that remains, however, is whether any of this is actually useful for patients!

It is up to dentists and dental hygienists not to react but rather to act! Guidelines for good toothbrushes need to be defined, for example, for periodontitis patients with thin gingiva, recession, large interdental spaces etc. Worthy of thought: A motivated patient brushes daily for 60, 70 or 80 years! Long-term freedom from injury is more important than momentary efficiency.

It seems that a start has been made: Superfine bristles—they clean just as well as hard bristles—and unconventional 3-headed brushes are being widely discussed.

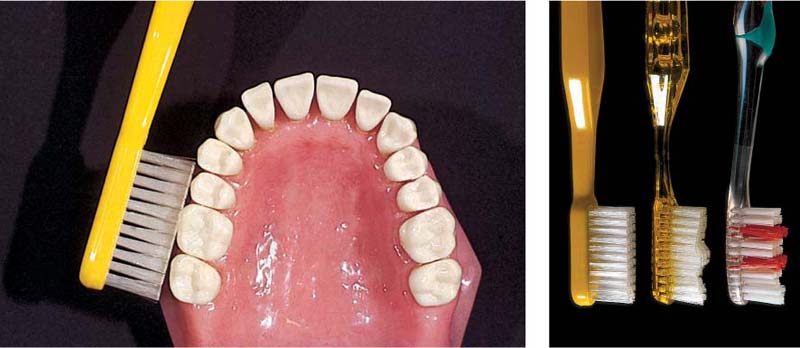

484 Modern Toothbrushes—Frontal View

How is one to evaluate the enormous differences in shape, bristle array, handle etc.?

The best that a toothbrush can offer is its ability to effectively clean the teeth, while preventing damage or injury to gingiva or teeth, and help reduce bad breath.

485 Modern Toothbrushes—Lateral View

This figure corresponds to Fig. 484. From left to right…

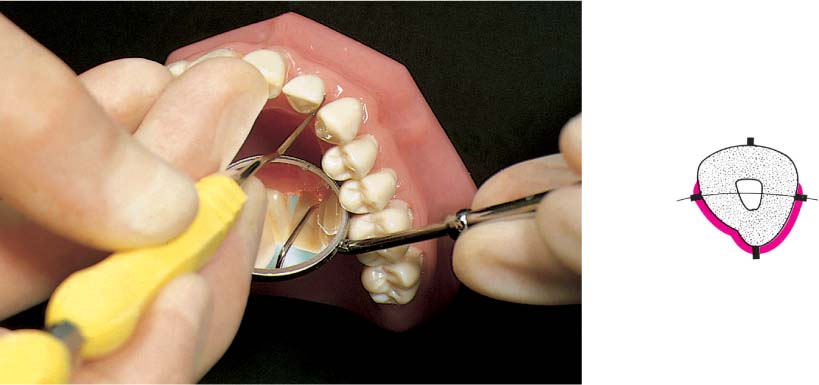

|

– Elmex |

Supersoft |

|

– Paro |

Future |

|

– Elmex |

Inter X medium |

|

– Trisa |

FlexHead soft |

|

– Dr. Best |

X-aktiv Flex |

|

– Oral-B |

Cross Action |

|

– Colgate |

Navigator medium |

|

– Mentadent |

Insider soft-medium |

|

– Superbrush |

Junior |

486 Meridol and Superbrush—New Developments; Progress?

Left: The Meridol brush has superfine, flexible bristles, designed to absorb excessive force.

Right: The three brush heads simultaneously clean vestibular, occlusal and oral tooth surfaces. Using a light vibratory movement, teeth are cleaned one-by-one. This design was superior to other brushes in clinical trials (middle: head of the Nais electric toothbrush. cf. p. 230).

Toothbrushing Technique

Innumerable toothbrush movements have been recommended over time, and then abandoned: Rolling, vibrating, circular, vertical and horizontal (Jepsen 1998). More important than the technique is the efficiency of cleaning, a systematic procedure and that no damage is caused.

Dentists and dental hygienists have recognized again and again that most patients, despite instruction, seem to be satisfied with an apparently “genetically determined” horizontal scrubbing technique.

The most frequently recommended “modified Bass technique” (Bass 1954) is depicted below.

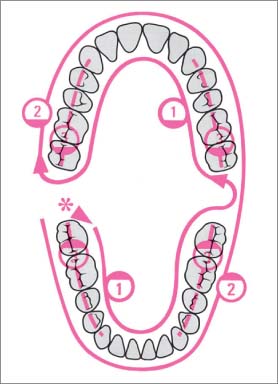

487 Systematic Toothbrushing

The sequence depicted has been shown to be effective (start: right, posterior*)

| 1 Oral Surfaces mandible/maxilla, and all distal surfaces at the end of each arch. 2 Facial Surfaces mandible/maxilla 3 Occlusal Surfaces mandible/maxilla 4 Interdental Spaces, using special hygiene aids |

Modified Bass Technique

488 Placement of the Toothbrush

Toothbrush bristles positioned perpendicular to the tooth long axis will not effectively clean the interdental spaces.

Right: Instead of the “original” Bass technique, which used a tworow brush, today the “sulcus cleansing technique” is performed with the more common three- or four-row brushes. This combination should provide improved cleaning.

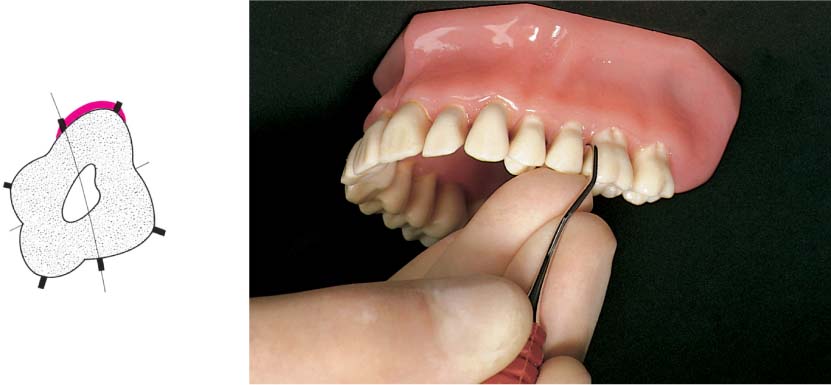

489 45° Angle of the Bristles—Occlusal View

When the brush is applied at a 45° angle to the teeth and then rotated toward the occlusal plane, the bristles slip easily into the interdental areas and gingiva sulci without excessive force. With the brush in this position, small rotatory or vibratory movements will effectively remove plaque.

Problem zone: Angular arch form in the canine regions.

490 45 Degree Angle—Distal Surfaces

Viewed from the distal, the position of the bristles in the Bass technique becomes obvious.

Right: Distal surfaces will not be effectively cleaned by hard bristle brushes; extremely flexible toothbrush bristles may provide effective distal cleaning.

Dental floss is not recommended for such surfaces, which often exhibit concavities and/or furcations. Single-tuft brushes are more effective (right).

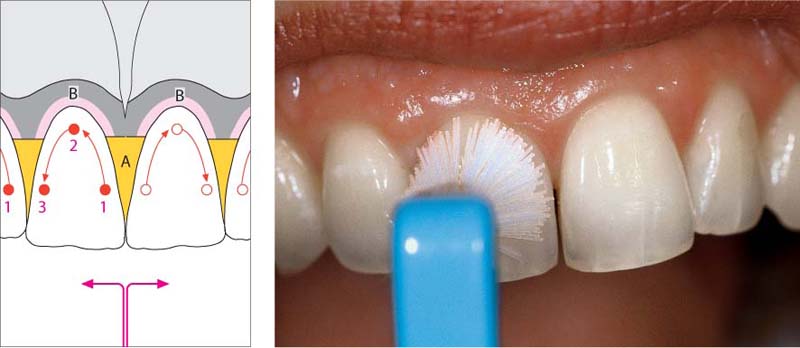

The Solo Technique—A Different Way to Brush Your Teeth

In 2000, Jiri Sedelmayer described the unreasonableness of the usual toothbrushing methods of many individuals: “Among other things, areas that scarcely need cleaning, such as prominent tooth surfaces and gingiva, are often injured. Notorious plaque-retentive areas, above all the interdental spaces, gingival sulcus and oral-distal tooth surfaces are regularly cleaned by only a disappearing few.” Sedelmayer was in fact correct, and in the same breath suggested a new technique, an alternative to the usual scrubbing, at least for individuals who are prepared to devote adequate time for their oral health.

The problem with classical toothbrushes is that when they are used with the recommended non-traumatic slight pressure, the niches are not achieved; with heavier force, however, prominent tooth surfaces and gingiva are so abused that true long-term damage is the consequence (recession, wedge-shaped defects etc; p. 456; Lussi et al 1993).

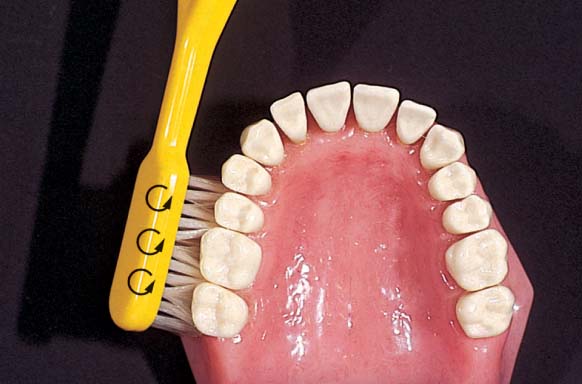

Using a soft, round, single-tuft brush with light force, the technique cleans tooth-by-tooth, above all the lingual aspects perfectly, including marginally and deep into the interdental space. However, other special hygiene aids are also necessary.

491 “Solo” Technique—Begin at Mesial of Tooth 11

The round, single-tuft brush is applied to the tooth surface with light force, and the bristles splay out. The mesial sulcus of tooth 11 is cleaned using minimal circular movements.

Left: An example of “solo” brushes, beginning (left) with the ages-old chewed twig!

Round “solo” brushes are commercially available from TePe, Curaden, Tandex etc.

492 Continuing Along the Gingival Margin…

The gingival margin and gingival sulcus are effectively de-plaqued, using the patient’s own sense of feel.

Left: Simple schematic—initiate tooth cleansing “from the middle toward the side” (e.g., tooth 11):

1 Mesial

2 Marginal

3 Distal

A Papilla

B Gingival Margin

493 … and Continuing Distally

The brush is guided distally and angled so that it achieves maximum contact with distal tooth surfaces, sulci and the papillary region.

This procedure is repeated for each tooth.

Left: What the classical brushes almost never accomplish: Perfect cleaning of the ligual marginal surfaces and interdental areas in the posterior segment of the mandible.

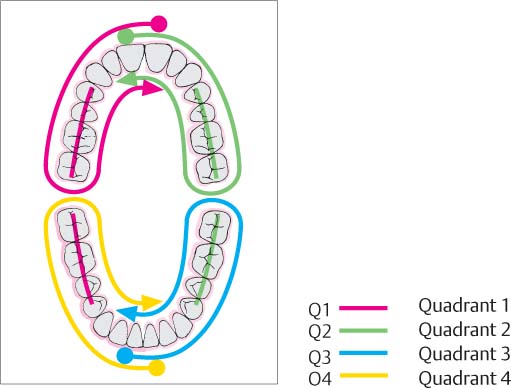

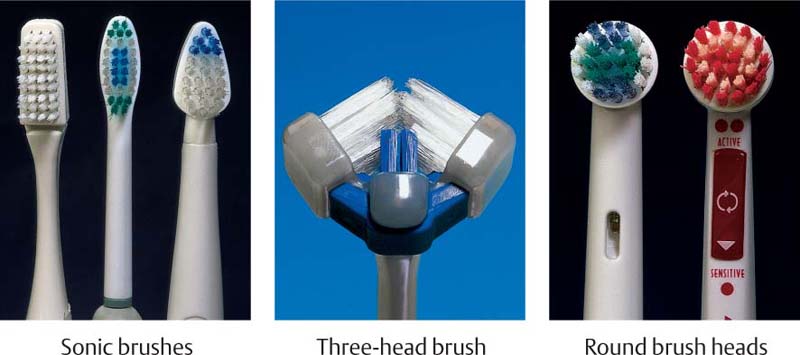

Electric Toothbrushes

Comparative clinical studies have shown that the efficiency in plaque removal of the newest electric toothbrushes is at least as good as that achieved with manual toothbrushes. Various products offer primarily advantages for persons with reduced manual dexterity, or the handicapped, but also offer an alternative to the hand toothbrush for highly motivated individuals. Preferred today are electric brushes with round heads, and sonically active toothbrushes, the latter because of their additional hydrodynamic activity (van de Weijden et al. 1996, Zimmer et al. 2000, Warren et al. 2001).

494 Effective Cleaning with Electric Toothbrushes

One can use the same system described for manual toothbrushes (Fig. 487) for the “quadrant system” built into some electric brushes. This provides 30 seconds of brushing per quadrant (see below; Q1-Q4).

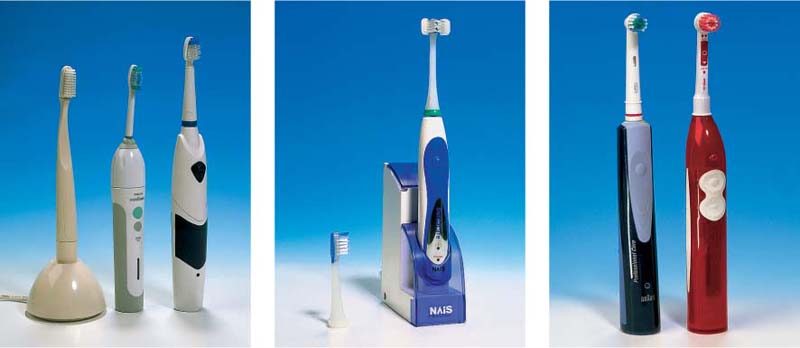

495 A “collection” of some commercially available electric toothbrushes

(from left to right)

| • Interplak • RotaDent • Philips Sonicare • Braun Oral-B • Waterpik • Ultra sonex • Roventa • Nais • Oralgiene |

496 Brush heads

The choice of a brush head is as important as the choice of the electric brush itself. With the high frequency brushes, there is a potential danger of gingival trauma. Brushes whose bristle movement stops when excessive force is applied should be recommended (e.g., Sonicare).

Each patient should be informed and instructed in the proper use of the electric toothbrush.

497 Current trends …

… include primarily sonic or combined sonic-ultrasonic toothbrushes, e.g., the Ultrasonex, Sonicare and Waterpik (left), the Nais electric toothbrush (middle; with its “normal” and three-unit head). The hydrodynamic effects of these brushes removes plaque even where the bristles cannot physically reach.

Brushes with round, rotating or oscillating heads are today mature products of high efficiency (Braun Oral-B, 5th generation and Trisa, right).

Interdental Hygiene

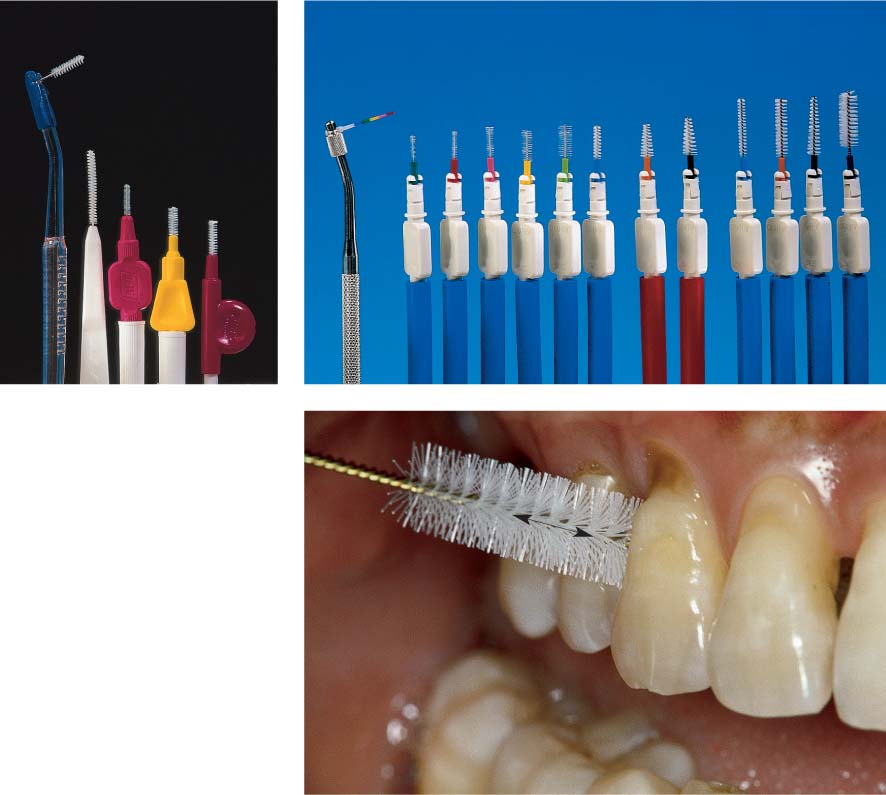

Gingivitis and periodontitis are usually more pronounced in the interdental area than on oral or facial aspects. Dental caries also occurs more frequently in the interdental region than on oral or facial smooth surfaces. Therefore, interdental hygiene, which cannot be achieved with the toothbrush, is of critical importance for periodontitis patients. The most appropriate interdental hygiene aids must be selected for each individual patient. The selection from the numerous commercially available devices depends for the most part on the morphological situation of the interdental spaces.

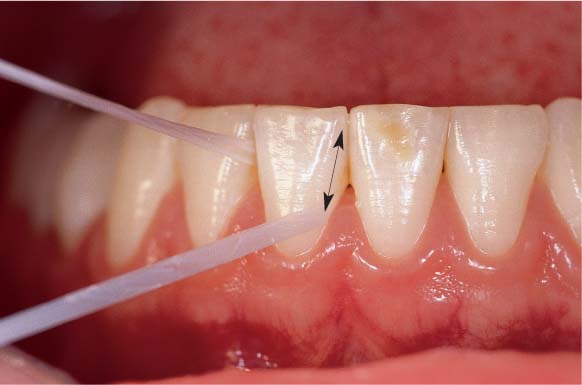

Dental Floss

The use of dental floss is indicated for healthy patients, and for gingivitis and mild periodontitis cases, as well as for patients with crowded teeth. It is well known, however, that the acceptance of dental floss (floss, tape, super floss) is quite low for most patients, especially males! Alternative interdental hygiene aids should be recommended even if these are less efficient than floss if patients will at least use them daily.

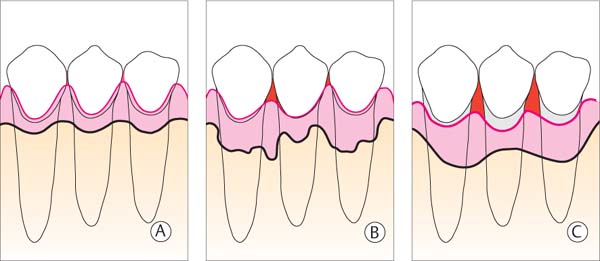

498 Morphology (schematic) of the Periodontium

| A Healthy B Periodontitis C Treated, Healed Periodontitis |

These three situations require differing techniques and various hygiene aids for interdental plaque control.

The diagrams portray the course of the alveolar bone, the gingival margin and the expanse of the interdental spaces (red).

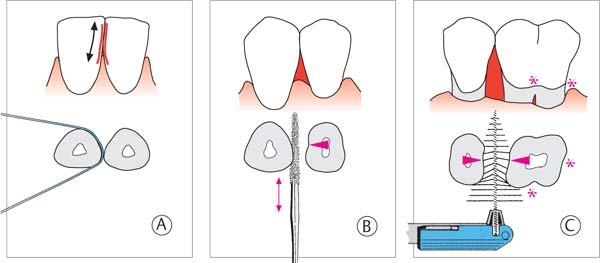

499 Size of the Interdental Space and Oral Hygiene Aids

The choice of a hygiene aid for interdental plaque control depends primarily upon the size of the interdental space.

| A Dental floss for narrow interdental spaces B “Tooth sticks” for slightly open interdental spaces C Interdental brushes for widely open interdental spaces, root concavities and grooves |

Toothpicks, Interdental Brushes