7 The orthodontic patient

treatment planning

One of the most difficult, but important aspects of orthodontic management is treatment planning. With the advent of modern fixed appliance systems it is deceptively easy to straighten teeth. The skill of the orthodontist lies in placing the dentition in the optimal position and achieving the correct aesthetic and occlusal result for each patient. This process starts with clinical examination, record collection and diagnosis. The next stage is treatment planning, which should ideally be carried out in a formal manner and away from the patient, using the clinical data and collected records. It is a two-stage process, initially defining the treatment aims and then deciding how these are to be achieved. In this chapter, treatment aims and the general principles of treatment planning are discussed. The specifics of treatment for different types of malocclusion are covered in Chapters 10 and 11.

Timing of treatment

However, there are disadvantages associated with starting treatment too soon. The overall duration will be extended, because almost inevitably a second phase of treatment will be required in the permanent dentition and this can lead to problems with compliance over the longer term. The original arch form and growth patterns will tend to reimpose themselves following the first phase of early treatment and a prolonged retention period may be required to maintain any correction during the transition from mixed to permanent dentition. Finally, there is a growing body of evidence to suggest that the treatment result for growth modification will be the same whether carried out in the early mixed or permanent dentition, the only difference being the increased duration if started early (Harrison et al, 2007). In the case of arch development in the early mixed dentition, the long-term results are poor, particularly with regard to the stability of tooth alignment (Little et al, 1990).

Aims of treatment

The principle aims of orthodontic treatment relate to aesthetics and function:

Facial aims

There is a greater awareness amongst orthodontists of the importance associated with facial and soft tissue aesthetics in treatment planning (Box 7.1). Obtaining a class I incisor and canine relationship is usually a fundamental aim of treatment, but this must not be achieved at the expense of the soft tissue profile. Reconciling the facial and occlusal aims of treatment can be difficult and will depend in part on the underlying skeletal relationship:

Box 7.1 Planning treatment around the face

In the infancy of orthodontics it was assumed that if all the teeth were aligned and the occlusal goals achieved, each individual would have ideal facial aesthetics. However, it soon become apparent that this was not the case, resulting in extreme protrusion of the dentition in some cases and extensive relapse in others. With the advent of cephalometric analysis, it was argued that facial growth was genetically determined and that orthodontic treatment could have little influence on the facial skeleton. Treatment became based around arbitrary hard tissue cephalometric standards, especially in relation to lower incisor position, even though these bear little relation to the soft tissues and facial profile (Park & Burstone, 1986). Since then, conventional thinking has shifted again, with the soft tissues defining the limits of orthodontic treatment in each individual (Ackerman & Proffit, 1997). The main reasons for this are a resurgence of interest in functional appliance therapy, advances in orthognathic surgical techniques, a greater understanding of orthodontic relapse and the acceptance of long-term retention strategies. There is also an appreciation of how the face ages and therefore how treatment carried out in the teenage years will impact on facial appearance many years into the future.

Occlusal aims

The occlusal aims of treatment are defined in terms of dental aesthetics and both static and functional occlusion (Table 7.1) and are generally listed in the order in which they will be corrected. Whilst these will vary between cases, in practical terms occlusal correction will usually require some or all of the following:

A further consideration related to the occlusion is health of the temporomandibular joints, but this is a contentious area. Despite evidence showing orthodontic treatment having little impact on temporomandibular dysfunction (Luther, 2007a, b), much conjecture exists regarding the ideal position for the condyle at the end of treatment and the need to treat to an ideal functional occlusion. However, orthodontics is one area in dentistry where treatment can result in significant occlusal change. Therefore it would seem sensible practice to aim for an ideal static and functional occlusion wherever possible.

Planning to achieve the facial aims of treatment

Treatment planning should begin with some consideration regarding the upper incisor position and whether this needs to be changed (Table 7.2). Achieving an ideal position for these teeth will be more difficult in the presence of a skeletal discrepancy and in some cases may not be possible with orthodontic treatment alone.

Anteroposterior position of the upper incisors

Conversely, the upper incisors can be positioned too far back within the face, resulting in a class III relationship. This can again be associated with dentoalveolar disproportion but is more commonly due to skeletal maxillary deficiency. A patient in the mixed dentition with marked maxillary deficiency may be a candidate for attempted growth modification to improve the maxillary position. This will require extraoral force to the maxilla provided by a facemask and reverse headgear. A rapid improvement in the incisor relationship can be achieved using this type of treatment; however, it requires excellent cooperation and the subsequent pattern of facial growth will significantly influence long-term stability of any change achieved (see Figs 10.45 and 10.46).

Lower incisor position

The planned upper incisor position will also need to be decided in relation to the lower incisors to achieve a class I relationship—a fundamental aim of treatment in most cases. Longitudinal studies have demonstrated that any labial movement of the lower incisors with an orthodontic appliance is inherently prone to relapse in the long-term (Mills, 1966, 1968). Therefore, as a general rule it is advisable to avoid proclining these teeth to any significant extent during treatment, although some exceptions to this do exist (Table 7.3).

Table 7.3 Clinical situations where lower incisor proclination may be acceptable

Class II malocclusion

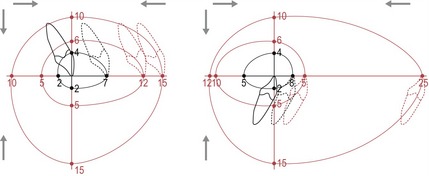

In moderate class II malocclusions, it may be possible to achieve a class I incisor relationship with orthodontic tooth movement alone. Camouflage treatment of this kind will usually involve mid-arch premolar extractions, maxillary incisor retraction and maintenance of lower incisor position (although some class II division 2 cases can be very demanding to treat in this manner without some lower incisor proclination). More severe class II cases, particularly those associated with mandibular retrognathia, may require significant upper incisor retraction to achieve camouflage, which can worsen a retrusive soft tissue profile as the lips move back with the teeth. There is not a simple relationship between incisor retraction and lip movement, and how far the lips can be acceptably retracted depends upon many factors, including their thickness and competence, the original incisor position and the underlying skeletal anatomy (Handelman, 1996; Ramos et al, 2005). However, care must be taken not to over-retract incisors, particularly in the more severe cases that already have a retrusive soft tissue profile.

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses