6 The orthodontic patient

examination and diagnosis

Successful orthodontic treatment begins with the correct diagnosis, which involves patient interview, examination and the collection of appropriate records. At the end of this process, the orthodontist should have assimilated a comprehensive database for each patient, from which the appropriate treatment plan can be formulated. Examination and record collection are discussed in this chapter, whilst treatment planning is the subject of Chapter 7.

Patient’s complaint and motivation

The demand for orthodontic treatment is primarily patient-driven and one of the most important components of an examination is the initial interview with the patient and their parent or guardian. It is important to ascertain what their main concerns are and the expectations of treatment. Over the past two decades there has been an increasing uptake in orthodontic treatment, with a greater awareness and demand for improved dental and facial aesthetics. Unfortunately this does not always accompany an appreciation of what orthodontic treatment involves (Tulloch et al, 1984). It can also be the case that the patient has no particular concerns regarding his/her dentition and it is the parent or dentist who has requested the consultation, which may make the acceptance of orthodontic treatment more difficult to obtain.

Dental history

Medical history

A number of medical conditions may impact upon the provision of orthodontic treatment:

Infective endocarditis

Bleeding disorders

Childhood malignancy

The commonest malignancies in childhood are the leukaemias, and amongst these, acute lymphoblastic leukaemia accounts for around 80% of cases. This condition mostly occurs in early childhood, before orthodontic treatment is routinely carried out. Treatment for a variety of malignancies in children often involves the use of radiotherapy, which can affect the tooth-bearing tissues. This may result in tooth agenesis and root shortening (Fig. 6.1). Orthodontic treatment should be delayed for these patients until they are in a period of remission and if diagnosis occurs during orthodontic treatment it is usually advisable to suspend treatment and remove the appliances. For patients with severe root shortening orthodontic treatment is contraindicated.

Allergies

Allergy to latex was first recognized in the 1970s and its occurrence has increased in recent years, particularly amongst healthcare workers following the universal adoption of wearing protective gloves. Latex allergy has been reported in orthodontic practice in relation to gloves and orthodontic elastics. The most common allergic response is a type IV delayed hypersensitivity reaction triggered by the chemical accelerators used in the manufacture of latex. This causes a localized contact dermatitis, typically associated with a pruritic eczematous rash. The IgE-mediated type I reaction is less common but has more serious consequences, including anaphylaxis. Amongst the general public, type I sensitivity has been estimated to occur in around 6% of the population (Ownby et al, 1996). Investigation is via skin prick testing or immunoassay. Patients with a confirmed type I allergy should be treated in a ‘latex-screened’ environment where potential exposure to any allergens is minimized. Synthetic gloves composed of vinyl or nitrile are available as an alternative to latex gloves, whilst the use of orthodontic elastomeric auxiliaries containing natural rubber latex should be avoided. Latex-free silicone elastics are available but show greater force decay and as such, require more frequent replacement.

Orthodontic wires and brackets contain nickel and nickel allergy is thought to be present in approximately 10% of Western populations and more common in females. It is usually a type IV allergic reaction related to the wearing of jewellery or watches and body piercing. Fortunately, oral reactions are rare, although prolonged exposure to nickel-containing oral appliances may increase sensitivity to nickel (Bass et al, 1993). Intraoral signs are nonspecific and have been reported to include erythema, soreness at the side of the tongue and severe gingivitis, despite good oral hygiene. Definitive diagnosis is usually achieved via patch testing. Stainless steel wires and brackets contain a relatively low proportion of nickel and are considered safe to use in a patient with diagnosed nickel allergy although titanium or cobalt chromium nickel-free brackets are available. In contrast, nickel titanium archwires have a much higher content, and should be avoided in these patients.

Extraoral examination

Assessment of the patient should begin with an examination of the facial features because orthodontic treatment can impact on the soft tissues of the face. Although a number of absolute measurements can be taken, a comprehensive facial assessment involves looking at the balance and harmony between component parts of the face and noting any areas of disharmony. Extraoral examination should start as the patient enters the room and it is important to look at the face and soft tissues both passively and in an animated state. Once in the dental chair, the patient should be asked to sit and the face examined from the front and in profile, in a position of natural head posture (Box 6.1).

Box 6.1 Natural head posture

Natural head posture (NHP) is the position that the patient naturally carries their head and is therefore the most relevant for assessing skeletal relationships and facial deformity. It is determined physiologically rather than anatomically and varies between individuals; however, it is relatively constant for each individual (Moorrees & Keane, 1958). As such, NHP should be used whenever possible to assess the orthodontic patient. The patient is asked to sit upright and look straight ahead to a point at eye level in the middle distance. This can be a point on the wall in front of them, or a mirror so that they look into their own eyes. Ideally NHP should also be used when taking a lateral skull radiograph, allowing the clinical examination to be related more accurately to the cephalometric data.

Frontal view

Vertical relationship

Vertically the face is split into thirds, with these dimensions being approximately equidistant. Any discrepancy in this rule of thirds will give an indication of disharmony within the facial proportions and where this lies. Of particular relevance is an increase or decrease in the lower face height. The lower third of the face can be further subdivided into thirds, with the upper lip falling into the upper third and the lower lip into the lower two-thirds (Fig. 6.2).

Lip relationship

The relationship of the lips should also be evaluated from the frontal view (Fig. 6.3):

Lip incompetence is common in preadolescent children and competence increases with age due to vertical growth of the soft tissues, especially in males (Mamandras, 1988).

Incisor show at rest

In adolescents and young adults, 3 to 4-mm of the maxillary incisor should be displayed at rest (Fig. 6.4). In general, females tend to show more upper incisor than males, with the amount of incisor show reducing with age in both sexes. An increased incisor show is usually due to an increase in anterior maxillary dentoalveolar height or vertical maxillary excess. Occasionally it is due to a short upper lip. The average upper lip length is 22-mm in adult males and 20-mm in females.

Incisor show on smiling

Ideally 75 to 100% of the maxillary incisor should be shown when smiling (Fig. 6.4), but this also reduces with age. Some gingival display is acceptable, although excessive show or a ‘gummy smile’ is considered unattractive (Fig. 6.4).

Smile aesthetics is also an important component of orthodontic treatment planning and should be formally assessed (Box 6.2).

Box 6.2 Aesthetics of the smile

During examination of an orthodontic patient the soft tissues should be assessed in animation and not just at rest. A key component of this is the smile. Smiling is an important part of communication and an unattractive smile can be a considerable social handicap, often providing a reason to seek treatment. Creating a pleasing smile is therefore a fundamental aim in orthodontics. Three principle characteristics of the smile need to be assessed (Sarver, 2001):

Pleasing gingival aesthetics. The gingival margin of the maxillary central incisors and canines are level, with the lateral incisor margin situated slightly below this. The embrasure spaces between the teeth (dotted lines) increase in size from the maxillary central incisors back. The connector areas (where the teeth appear to meet and indicated by red arrows) should be approximately 50, 40 and 30% of the maxillary central incisor crown length for the maxillary central incisors, central-lateral incisors and lateral incisors-canines, respectively (left panel). The maxillary incisor edges should also lie parallel to the curvature of the lower lip to produce a consonant smile arc (right panel) (Gill et al, 2007).

Transverse relationship and symmetry

The transverse proportions of the face should divide approximately into fifths (Fig. 6.5). No face is truly symmetrical; however, any significant facial asymmetry and the level at which it occurs should be noted. This can be done by assessing the patient from the front and also from behind and above, looking down the face (Fig. 6.6). The relative position of each dental midline to the relevant dental base should be recorded. Asymmetries of the lower face are particularly common in class III malocclusion with mandibular prognathism.

Mandibular asymmetry has been described as primarily of two types (Obwegeser & Makek, 1986):

Profile view

The facial profile should be assessed anteroposteriorly and vertically.

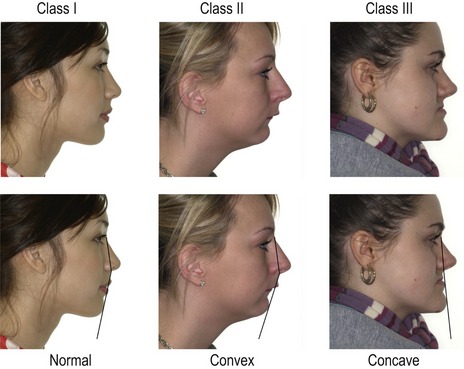

Anteroposterior relationship

An assessment should be made of the skeletal dental base relationship between the upper and lower jaws in the anteroposterior plane (Fig. 6.7). This can be achieved by mentally dropping a true vertical line down from the bridge of the nose (often called the zero meridian). The upper lip should rest on or slightly in front of this line and the chin slightly behind. Alternatively, the dental bases can be palpated labially.

Figure 6.7 Skeletal class I (left), class II (middle) and class III (right) profiles.

Facial convexity can also be described in relation to the angle between the upper and lower face.

An assessment can also be made of the angle between the middle and lower third of the face (Fig. 6.7), with the profile being described as:

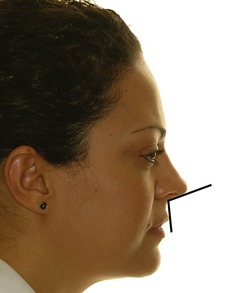

Nasolabial angle and lip protrusion

The nasolabial angle is formed between the upper lip and base of the nose (columella) and should be between 90° and 110° (Fig. 6.8). It gives an indication of upper lip drape in relation to the upper incisor position. A high or obtuse nasolabial angle implies a retrusive upper lip, whilst a low or acute angle is associated with lip protrusion.

Vertical relationship

The face can also be divided into thirds as described earlier and direct measurements made of the facial heights (Fig. 6.9).

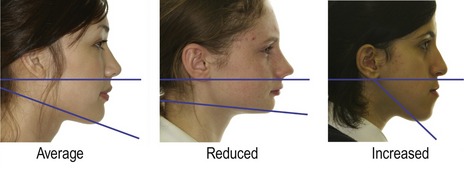

The angle of the lower border of the mandible to the cranium should also be assessed. This can be done by placing an index finger along the lower border and approximating where this line points. If it points to the base of the skull around the occipital region, the angle is considered average. If it points below this, the angle is reduced, whilst above it the angle is increased (Fig. 6.10). This usually, but not always, correlates with measurements made of the anterior face height.

Intraoral examination

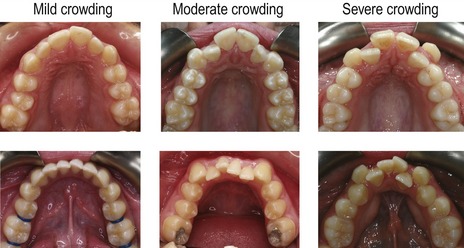

Dental arches

Static occlusion

Overjet

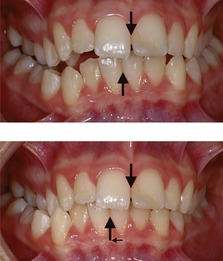

The overjet should be measured from the labial surface of the most prominent maxillary incisor to the labial surface of the mandibular incisors (Fig. 6.14). The normal range is 2 to 4-mm. If there is a reverse overjet, as can occur in a class III incisor relationship, this is also measured and given a negative value.

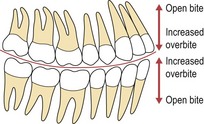

Overbite

The normal range is for the maxillary incisors to overlap the mandibular by 2 to 4-mm vertically, or one-third to one-half of their crown height (Fig. 6.15). Overbite is described as:

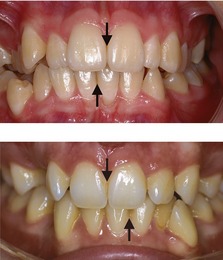

If the overbite is complete to the gingival tissues, it is described as traumatic if there is evidence of damage. This is most commonly seen on the palatal aspect of the upper incisors or labial aspect of the lower (Fig. 6.16).

Anterior crossbite

Teeth in anterior crossbite should also be noted along with the presence and size of any displacement of the mandible that may occur when closing in the retruded contact position (RCP) into the intercuspal position (ICP) (Fig. 6.17). An anterior crossbite with displacement can cause labial gingival recession associated with the lower incisors in traumatic occlusion, which if present, should be recorded.

Buccal segments

The buccal segment relationship is described using the Angle classification (see Chapter 1). The molar and canine relationships should also be noted (see Fig. 6.14).

Posterior crossbite

Orthodontic records

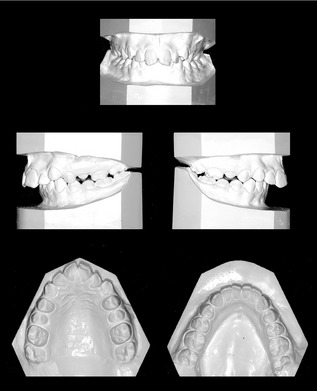

Study models

Impressions showing all the erupted teeth, full depth of the palate and good soft tissue extension are needed. These can be taken in alginate for study models and poured in dental stone (Fig. 6.23). A wax or polysiloxane bite should be taken with the teeth in ICP (Box 6.4). Orthodontic models should be trimmed with the occlusal plane parallel to the bases, so the teeth are in occlusion when the models are placed on their back. The bases are also trimmed symmetrically so the archform can be assessed and they are neat enough to be used for demonstration to the patient.

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses