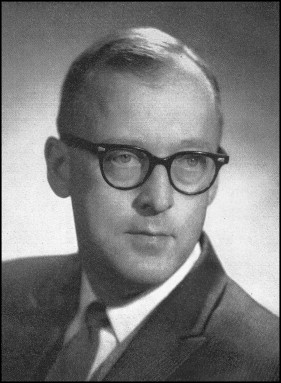

Who can best take the measure of a teacher? His students—for whom I speak. I am singularly pleased and proud to have been asked to join in this tribute, since I have long felt a debt of gratitude to Alton Moore which in this small way I can publicly acknowledge, and perhaps in some measure, repay.

A man turns many faces to the world as he builds his life, and many people come to know him in many ways. Sometimes wearing the mantle of the scholar, he plays out the role of the “Outstanding Authority” for a few hours on a lecture platform. A demanding role this, but perhaps not really so difficult with preparation and practice.

To some he is known as an “Organization Man,”—executing the commission of an office, or bearing the responsibility of administration ably and efficiently for a term, or arranging a meeting or two. A response to the heady call of duty and glory in the limelight of the speakers’ table; this, too, may not be so formidable, especially for a man with a good secretary.

To still others Alton Moore is the “Researcher,”—meticulous and incisive, whose contributions have been a major influence in orthodontic thinking in these 10 years. Even this highly creditable role requires the support of a good department and hard working graduate students, and that Dr. Moore saw to it that he had them is certainly the more to his credit.

The people who know Alton Moore in these roles, as Lecturer, Organization Man, Administrator, Researcher,—may know him well and claim the right to praise him, and I would not seek to detract from this well-deserved accolade. But it is we, his students, who can really take his measure as a Teacher, and he is above all a Teacher. The more so since we are more than Moore’s students, we are his friends, and there are few teachers who can allow their students to become their friends. We, his students, really know him, the every day unvarnished Al Moore,—“The Chief.”

When we began our training, the six of us who made up the tail end of the first class, and met Dr. Moore, we felt from the first that here was a different sort of teacher. A man with a calm proficiency in his field whose depth of understanding and insight made pretentiousness unnecessary. As class succeeded class, their feelings toward him have remained the same. It is well known that any strong teacher develops a sort of climate peculiar to his department. We sensed the kind of discipline he was to build. It began with mutual respect and the most astonishing demands for high performance both technically and didactically, that any of us had ever met. I for one was appalled at what this quiet, serious man was asking of us. The technique procedures were impossible and the sheer weight of reading and study was staggering.

Then began the remarkable experience of being taught by Professor Alton Moore. For him teaching is a creative process, and there is an almost tangible feeling of order and growth of the body of knowledge. And then, as part of the teaching process, we began to feel the warmth of his friendship and to understand that these demands were made out of his conviction that they were essential to proper orthodontic training, and his confidence that this level of requirement was within our capabilities. To fail would have been to disappoint a friend. This friendship and confidence remained an essential part of our discipline throughout our training and is still a part of our relationship with him.

Dr. Moore’s selection of his faculty and the outstanding level of their performance was another example, I think, of the syndromic effect of his influence. They, too, must have felt the quiet integrity and the warmth he generated to have joined so wholeheartedly and effectively to supplement and complement him. I am sure that never before in orthodontic education was there assembled so competent and well balanced a faculty as “The Chief” gathered for us and for each new class. I distinctly remember the genuine anticipation with which I greeted each day and the excitement of each new step along the path they laid out.

What was there that distinguished the teaching? For me it was the principles before techniques. (I’ll never forget Dr. Riedel’s look of absolute scorn when I insisted on knowing just which line on a cephalometric analysis was the one to be drawn in red pencil.) Historically in orthodontics there have always been strong and often divergent “schools of thought” which rallied around their leader and identified with his name and his appliance variation,—and became the more static as their importance increased. This tyranny of technique is evident in a good bit of orthodontic education today. Men’s names are still actively connected to certain mechanical effects or cephalometric procedures. A technical procedure suddenly becomes a “Philosophy,” and mechanical specifications are confused with biologic principles. Perhaps it was the mixture of backgrounds of the staff that accounts for it, and the fact that all of them knew each other well. In any case, the obvious respect that the faculty members held for each other and their obvious competence in spite of differences in technique made it evident to us that there were few pat answers. In any case, the end result was an assurance that orthodontics is built on biology, not mechanics. To Alton Moore’s great credit there was never, and probably will never be a Moore Philosophy.