Armamentarium

|

| Alternative Instruments |

|

History of the Procedure

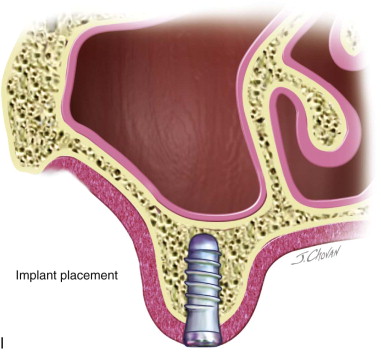

The sinus lift procedure is a technique of bone reconstruction along the maxillary sinus floor. It is designed to increase the vertical posterior maxillary alveolar dimension for placement of dental implants. Dr. O. Hilt Tatum proposed the first sinus lift procedure in 1976 at an implant meeting in Birmingham, Alabama. However, in 1980 Boyne and James became the first to publish this surgical technique, followed by Tatum, also in 1980. The sinus lift technique has undergone numerous modifications since its introduction. These procedures are routinely performed on an outpatient basis, without a hospital stay.

With the evolution of predictable sinus lift methods, this technique has become one of the primary surgical options allowing placement of dental implants in the posterior maxilla. The principles of the sinus lift procedure are simple; however, a number of anatomic variations and techniques should be considered to achieve reliable outcomes.

The apex of the sinus extends to the zygomatic process of the maxilla. The floor of the maxillary sinus is approximately 1 cm below the nasal floor in dentate adults. The base of the pyramid contributes to the lateral wall of the nasal cavity. The three-sloped walls of the pyramid are formed by the orbital floor and the anterior and lateral walls of the maxillary sinus. The sinuses are theorized to reduce the weight of the skull, provide resonant function, regulate the inhaled air humidity, and pneumatize with age. Adult males have larger maxillary sinuses than females. The approximate dimensions of the maxillary sinus in adult males are 21 to 29 mm in width, 39 to 49 mm in height, and 36 to 43 mm in length. In adult females these dimensions are 19 to 27 mm in width, 35 to 45 mm in height, and 33 to 41 mm in length. Maxillary sinus volume is approximately 5 to 35 mL, depending on the referenced literature.

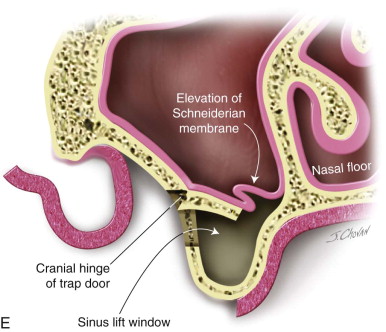

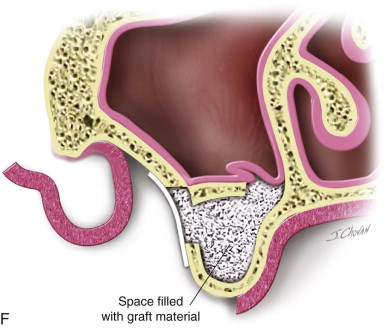

The maxillary sinus is lined with ciliated columnar epithelial cells, which clear secretions toward the ostia. This thin membrane is also called the schneiderian membrane. The medial wall of the sinus has an opening (ostia) that connects the sinus with the nose. The opening is in the hiatus semilunaris, which drains into the middle meatus of the nasal cavity. Gosau et al. reported that the location of the semilunar hiatus ranges from approximately 18 to 35 mm (mean, 25.6 mm) above the nasal floor. The orbital floor of the maxilla contains blood vessels and the infraorbital nerve. The maxillary sinus receives its blood supply from branches of the internal maxillary artery, including the infraorbital, sphenopalatine, greater palatine, and alveolar arteries.

History of the Procedure

The sinus lift procedure is a technique of bone reconstruction along the maxillary sinus floor. It is designed to increase the vertical posterior maxillary alveolar dimension for placement of dental implants. Dr. O. Hilt Tatum proposed the first sinus lift procedure in 1976 at an implant meeting in Birmingham, Alabama. However, in 1980 Boyne and James became the first to publish this surgical technique, followed by Tatum, also in 1980. The sinus lift technique has undergone numerous modifications since its introduction. These procedures are routinely performed on an outpatient basis, without a hospital stay.

With the evolution of predictable sinus lift methods, this technique has become one of the primary surgical options allowing placement of dental implants in the posterior maxilla. The principles of the sinus lift procedure are simple; however, a number of anatomic variations and techniques should be considered to achieve reliable outcomes.

The apex of the sinus extends to the zygomatic process of the maxilla. The floor of the maxillary sinus is approximately 1 cm below the nasal floor in dentate adults. The base of the pyramid contributes to the lateral wall of the nasal cavity. The three-sloped walls of the pyramid are formed by the orbital floor and the anterior and lateral walls of the maxillary sinus. The sinuses are theorized to reduce the weight of the skull, provide resonant function, regulate the inhaled air humidity, and pneumatize with age. Adult males have larger maxillary sinuses than females. The approximate dimensions of the maxillary sinus in adult males are 21 to 29 mm in width, 39 to 49 mm in height, and 36 to 43 mm in length. In adult females these dimensions are 19 to 27 mm in width, 35 to 45 mm in height, and 33 to 41 mm in length. Maxillary sinus volume is approximately 5 to 35 mL, depending on the referenced literature.

The maxillary sinus is lined with ciliated columnar epithelial cells, which clear secretions toward the ostia. This thin membrane is also called the schneiderian membrane. The medial wall of the sinus has an opening (ostia) that connects the sinus with the nose. The opening is in the hiatus semilunaris, which drains into the middle meatus of the nasal cavity. Gosau et al. reported that the location of the semilunar hiatus ranges from approximately 18 to 35 mm (mean, 25.6 mm) above the nasal floor. The orbital floor of the maxilla contains blood vessels and the infraorbital nerve. The maxillary sinus receives its blood supply from branches of the internal maxillary artery, including the infraorbital, sphenopalatine, greater palatine, and alveolar arteries.

Indications for the Use of the Procedure

The primary indication for the sinus lift procedure is pneumatization of the maxillary sinus, which prevents the placement of dental implants in the posterior maxilla. Poor bone quality that prevents adequate initial stability during implant placement is another indication. Dental extraction in the posterior maxilla appears to be partly responsible for pneumatization in elderly patients. The alveolar process forms the sinus floor, which is situated below the nasal floor level. The curved sinus floor conforms to the conical root apices of posterior maxillary teeth. McGowan and James explained the pneumatization of the maxillary sinuses with respect to dental extraction and age. Sharan and Madjar reported that sinus pneumatization occurred in an inferior direction after extraction of maxillary posterior teeth.

Preoperative planning is essential for successful management of the patient. This includes a careful history and physical exam, in addition to preoperative radiologic investigation, which could include conventional sinus radiographs, an orthopantomogram, and/or a computed tomography (CT) scan to evaluate for and rule out any contraindication to the sinus lift procedure.

Limitations and Contraindications

Conditions blocking the ventilation and clearance of the maxillary sinus are the main contraindication to the sinus lift procedure. Many of these causes are reversible and should be treated before the sinus lift procedure. Questions designed to elicit risks for sinus obstruction should be asked as part of the preoperative assessment. These risks may include a history of smoking; allergic rhinitis; previous nasal surgery or trauma; a history of chronic and/or recurrent sinusitis (the former defined as a sinus infection lasting more than 4 weeks and the latter as at least four episodes of acute sinusitis in the previous 12 months or at least three episodes in the previous 6 months); chronic use of nasal steroids and/or vasoconstrictors; chronic nasal obstruction and/or rhinorrhea; chronic hyposmia and/or hypogeusia; previous treatment for head and neck neoplasms; and comorbidities, particularly systemic diseases and pathologies that interfere with mucosal composition or ciliary movements (e.g., primary or secondary immunodeficiencies, cystic fibrosis, Kartagener’s and Mounier-Kuhn’s syndromes, dehydration, ciliostatic drugs, peripheral hypereosinophilia, asthma, chronic pulmonary disease, and acetylsalicylic acid hypersensitivity).

The maxillary sinus cavity is frequently interrupted with septa and bony ridges. The incidence of maxillary sinus septa was reported to be 14% to 33%. The main location of the septa was the region of the first and second molars. When septa were identified in one maxillary sinus, there was a 66% to 70% chance of the same sinus configuration on the contralateral side. This may make it difficult to perform a sinus lift. A preoperative cone beam computed tomography (CBCT) scan can be helpful in planning the surgery and determining whether a lateral or transalveolar approach would be the better choice.

The size of maxillary sinuses substantially affects the sinus wall thickness. If the sinus is large, the walls may be thin, and the converse also is often true. Small sinuses also may have thick osseous lamellae. Yang et al. reported that the lateral wall of the maxillary sinus emerges as a thick cortical plate at the first premolar area, becomes thinner in the posterior direction, and then increases in thickness to the first molar area in dentate skulls. Zijderveld et al. reported that 78% of lateral sinus walls were thin, and 48% of maxillary sinuses had septa. The mean thickness of the maxillary sinus ranged from 0.5 to 2 mm. Amin and Hassan and Yang et al. showed that there were no significant differences in the thickness of the lateral wall according to patients’ age. These results also suggest that lateral pneumatization is not age related, contrary to the findings of Lee et al., who described a gradual increase in volume of the paranasal sinuses with age.

If the lateral sinus wall is thick, the entire sinus window should be thinned out to assist the elevation of the schneiderian membrane and avoid perforation. The schneiderian membrane should be kept intact to contain the graft material and provide a vascular bed for it. Clinical evaluation of the lateral sinus wall can provide valuable information during surgery. If the lateral sinus wall is thin and looks grayish blue, the outline of the sinus can be determined easily. Transpalatal illumination can also help determine the location of the sinus.

Technique: Sinus Lift—Lateral Approach

Step 1:

Incision

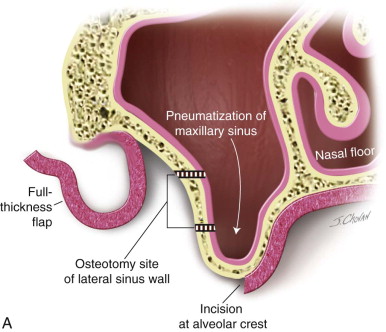

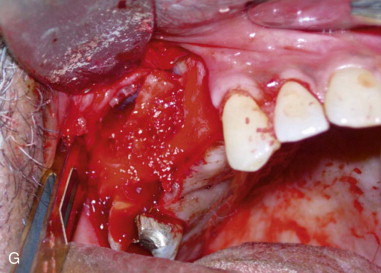

A crestal or slightly palatal incision is made over the alveolar crest through the keratinized oral mucosa. The remainder of the incision is dictated by the presence or absence of teeth. When the ridge is edentulous and bilateral sinus lifts are planned, the crestal incision extends anteriorly, crossing the midline to the opposite side. Releasing incisions are made posterior to the tuberosity. When teeth are present or when a unilateral sinus lift is planned, the crestal incision extends over the posterior edentulous region, with a releasing incision that begins anterior to the anterior extent of the sinus, usually in the canine region. The posterior extent is to the tuberosity region, with a releasing incision posterior to the tuberosity. This trapezoidal flap, which is designed to be broad based, allows minimal disturbance of the blood supply, sufficient coverage of the surgical wound, and adequate access for the lateral sinus osteotomy, with graft placement and simultaneous implant placement if indicated.

Step 2:

Exposure

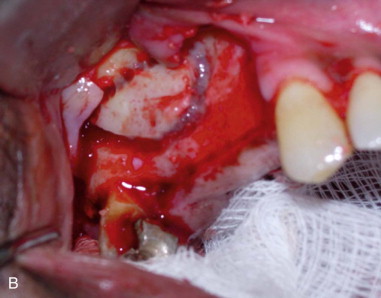

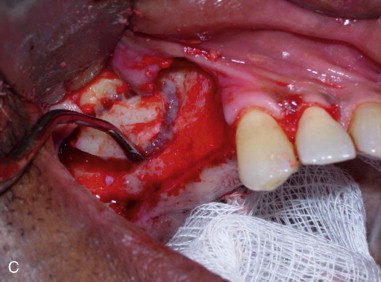

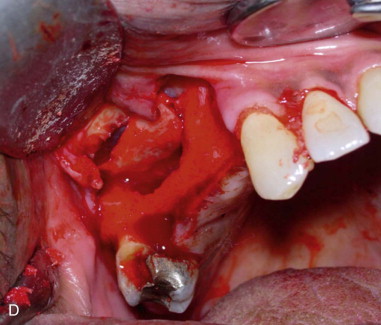

The full-thickness flap is elevated, exposing the lateral wall of the maxillary sinus ( Figure 22-1. A ). The infraorbital neurovascular bundle is usually identified anteriorly and superiorly and protected.

Step 3:

Osteotomy

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses