The history of orthodontic education in the United States spans more than 100 years. A number of exhortations have been repeated over the years by some of the best minds in orthodontics. First, our standards of excellence must be maintained. Angle set a standard for the specialty by demanding that students in his proprietary school achieve a high level of knowledge in growth and development, biomechanics, and mechanical skills; that standard is no less important today in postgraduate orthodontic departments. Second, orthodontics is not just moving teeth. Throughout our history, authors have stressed that teeth are “incidental” to orthodontics, and we need to be concerned with bone and the dentofacial complex. To be sure, much has changed about our specialty and its biologic foundations; we must adapt along with the discoveries in biology and the innovations in technology. But we should always strive for excellence—in ourselves and our specialty.

Highlights

- •

The history of orthodontic education in the United States spans more than 100 years.

- •

Angle set a high standard for students in his private schools.

- •

We should maintain that level in university education today.

- •

Our focus should be on bone and the dentofacial complex, not just on moving teeth.

The history of orthodontic education in the United States spans more than 100 years. Today’s orthodontists are most familiar with the issues that have caught our attention over the last decade: the shortage of orthodontic faculty and whether we are opening too many new postgraduate programs. Today’s orthodontists might reasonably assume that these same issues were important in previous decades. It is most interesting to read accounts of the discussions and thoughts that took place up to 90 years ago as our specialty matured and developed.

Orthodontics has been an academic discipline since the 18th century, when Fauchard published a systematic assessment of orthodontics. Kingsley, who is often considered the father of orthodontics, lectured to students on the benefits of orthodontic treatment in the 1870s. Other educators such as Eugene Talbot and Simeon Guildford published textbooks on orthodontic treatment for students in the dental colleges. There were no postgraduate programs in the discipline.

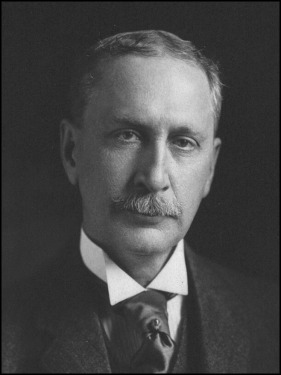

Edward H. Angle ( Fig 1 ) entered the scene in the 1880s, when he taught orthodontics in several dental schools in the Midwest. He developed his system of “regulating teeth” and published the first edition of his book, Malocclusion of the Teeth , in 1886. However, in the late 1800s, he opened his own school because he was not successful in convincing dental schools to form departments of orthodontics. The Angle School of Orthodontia opened in St Louis and, from 1900 to 1911, produced many outstanding orthodontists. Dr Angle developed a rigorous curriculum that included anatomy, histology, zoology, and art. He also required preliminary examinations to those who sought to learn the specialty at his school.

Because of the Angle School the demand for such schools increased, and many proprietary schools opened to fill the need for orthodontic specialists. However, most of these schools lacked the biologic foundation of the Angle School and tended to rely solely on mechanical training. These proprietary schools were viewed with disapproval by the profession because of the limited training they provided, and efforts were made to bring specialty training into university dental schools.

The 1920s

The predominant theme of the 1920s was the proper education of orthodontists. To understand the issues surrounding this concern, it is important to realize that dental education was also evolving, and it was unclear just how orthodontics would fit into the larger sphere of dentistry.

Although orthodontics had, until this time, been a part of the predoctoral curriculum, many people thought that postgraduate education would be necessary. Martin Dewey addressed the New York Society of Orthodontists in 1924 and gave a sampling of the variety of thoughts and opinions regarding postgraduate education in orthodontics. Dewey reported that some thought that a 1-year internship would be sufficient. Others believed that “unless the student comes in actual contact with the clinical cases of various classifications, while under treatment from beginning to end, can he hope to obtain sufficient knowledge and skill to be of any value” (p. 529). Finally, “one year’s experience in clinical work is not sufficient to acquire adequate knowledge to treat an orthodontic case successfully from beginning to end, much less learning anything of diagnosis and prognosis” (p. 530). Dewey concluded that there was so much “disagreement in dental schools, universities and teachers that it is practically impossible at the present time to agree upon any one definite plan” (p. 530). He cautioned, however, that any program must not only produce enough orthodontists to meet the demands of the public, but also be acceptable to the majority of those desiring to become orthodontists, in regard to both the length of the program and the requirements for completion. He concluded by recommending a short, intensified course of 8 to 10 weeks for the general dentist who wants to practice orthodontics, and a long course of a year or more that would lead to a master’s degree.

In 1926, Joseph Eby gave a lengthy talk to the American Society of Orthodontists in which he reviewed trends and problems in orthodontics, including education. He believed that orthodontics required a “sweeping reform” and needed to establish some “truths of natural laws” that formed the foundation of orthodontics. Eby thought that orthodontics had become a purely mechanical exercise that was too dependent on opinion for its guidelines. Research was needed to determine the correct amount of force for moving teeth because, in Eby’s words, “there can then be one and only one proper degree of assistance, whether it be mechanical, muscular, or otherwise” (p. 627). He maintained that teeth are “but incidental objects” whose positions were corrected, but that orthodontists must first be concerned with bone. Eby believed that orthodontic education was part of this general problem, and he proposed roles for both undergraduate and postgraduate education. In undergraduate education, orthodontics should be placed in the context of all the other disciplines to give students “a true vision of orthodontia” (p. 630) so that they could diagnose malocclusion and undertake interceptive treatment. The postgraduate program should educate students to treat patients in a university. He saw 2 types of postgraduate programs: one for the new graduate, who was not constrained by an office or a family and could spend a year at a university, and another for the experienced practitioner, whose maturity and judgment would allow him to learn by a correspondence course over a longer period of time. Thus, he called upon the specialty to establish “uniform principles of treatment” to define the specialty.

That same year, James McCoy, a faculty member at the University of Southern California, wrote some suggestions for orthodontic education. McCoy thought that the trouble in predoctoral education stemmed from 2 problems. First, orthodontics was thought to involve manipulation of mechanical devices only, so that teaching this topic was limited to this. Second, so few hours were devoted to teaching orthodontics as opposed to prosthetic dentistry (64 vs 608) that predoctoral instruction was greatly restricted to the most basic principles. McCoy stressed that until enough of the biologic background could be incorporated, orthodontics could not be properly taught. A corollary to this dictum was that as long as orthodontics was considered a “minor” course, it could not be properly taught. He recommended that 3 courses be taught to undergraduate students: a lecture course, a technique course, and, if orthodontics was elevated to a major subject, a clinical course.

McCoy recommended that a postgraduate course should consist of an internship year, during which the intern would “not only receive the undergraduate instructions in orthodontia but amplified instructions in both theory and technic, be allowed to assist demonstrators… and finally to conduct in the clinic a miniature orthodontic practice” (p. 822). He then detailed the qualifications for such an intern and gave in great detail the requirements for each portion of the course.

The 1930s

Discussion in the 1930s focused on the type of education that would be most effective. Early in 1930, Richard Summa from St Louis questioned why orthodontic postgraduate education had to be extended over a year or more, and he disagreed with those who thought that general dentists could not handle the information. He felt that “the value of each branch (of medical science) is measured by its success and availability… . [N]o phase of orthodontia is beyond the comprehension of any graduate dentist.”

One primary reason for extending the length of orthodontic education was to enable students to treat patients longitudinally. Summa stated, “the clinical phase of orthodontic instruction is the difficult problem confronting schools and is insurmountable if it be required that students treat and observe cases from beginning to end.” He postulated that it would be impossible for anyone, instructor or student, to ever see and treat all possible variations of malocclusion during his or her lifetime, so that orthodontic instruction by necessity must be “typal.” Summa recommended that short courses similar to the Angle School should be held at universities, and that the school should “carry” patients who are treated in an ongoing fashion, with students observing them during short courses.

Later that year, T.W. Sorrels wrote from Oklahoma about the increase in dental disease and malocclusion in the general public, and the inability of orthodontists to serve the public. Contrary to Summa, however, he thought that dentistry had become so complex that it was impossible for any one person to “expertly” practice all aspects. He noted that oral surgery and orthodontics were recognized as specialties and that pediatric dentistry, periodontia, and prosthodontia were gaining recognition as such. Sorrels believed that “the obligation of the universities to provide a systematic curriculum for the training of specialists in orthodontia… is clear and urgent” (p. 797) and that in all but 4 schools, proper courses were not being provided.

Sorrels thought that both universities and the public (through government funding) should assist in the training of orthodontists, and he proposed some changes that could be made to make sure that more patients were served. Although predoctoral education at that time was 5 years, he suggested lengthening each year from 9 to 11 months so that the curriculum could be accommodated in 4 longer years. Predoctoral students could major in orthodontics to determine their aptitude for the subject and then continue on for an optional full year of graduate studies in orthodontics. This additional year would culminate in a master’s degree, and a second year would be available for further studies, research, and a doctoral degree. He suggested that opportunities could be provided for others to enter the specialty by offering this course in sections.

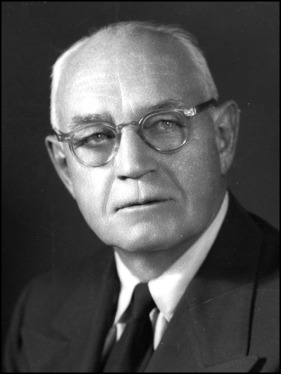

The issue was apparently not solved by 1936 when Spencer R. Atkinson ( Fig 2 ) and David W. McLean added their views on what education was needed. They observed that although orthodontics was becoming more complex, with additional considerations given to endocrine and metabolic disturbances, masticatory function, and the relationship between malocclusion and periodontal disease, there was a trend toward “simplifying and cheapening” (p. 209) orthodontic services. They explained that there were 2 kinds of simplicity: that of efficiency, and that of ignoring details and compromising ideals. The bulk of their article detailed situations in which faulty posture, endocrine disturbances, faulty swallowing, occlusal abnormalities, and muscle pressure posed problems that the orthodontist needed to address. They concluded that these additional issues needed to be included in the orthodontic curriculum to optimize results and prevent relapse. Consequently, they observed that a mere technique class of 8 to 10 weeks would not be enough to fully educate orthodontists, since orthodontics was no longer simply tooth movement. They stated, “The day of the private orthodontic school is past. Orthodontic education must be carried on in universities where… the knowledge contained in various scientific departments of a university can be pooled, correlated, and applied to the orthodontic problem” (p. 217).

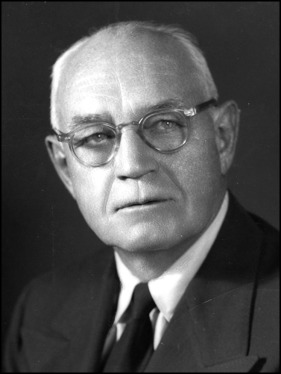

Two years later, H.C. Pollock ( Fig 3 ) wrote an editorial on the subject of orthodontic education. He observed that 40 years earlier there had been no specialty of orthodontics, but presently, although orthodontics was a well-recognized specialty, there was still no single method of training to be an orthodontist. He acknowledged that many would still recommend observing in a private office for some months, in addition to taking a practical course at a university. Pollock noted that orthodontists were often accused of being indifferent to the public welfare and of discouraging others to become orthodontists, but he theorized that this was not out of selfishness but was because there was no good method for education. University dental schools, for the most part, were not equipped for postgraduate education, since they had a difficult time recruiting excellent faculty because of financial pressures. He directed responsibility for these problems at the universities and hoped that a university with sufficient resources, in terms of both finances and faculty, would “save orthodontics from its present role as the stepchild of dentistry” (p. 403).

William J. Gies, a biochemist from Columbia University, had gained recognition in the dental community for his comprehensive, 250-page report on dental education that established the importance of dentistry in health care and stressed the role of universities in dental education. At a meeting of the New York Society of Orthodontists in 1938, he spoke about the need for the involvement of universities in educating orthodontists. He compared the education at proprietary orthodontic schools and universities, and while he acknowledged that some proprietary schools “stimulated and sustained the development of orthodontics” (p. 524), he maintained that universities should be preferred because most proprietary schools had a dominant profit motive. He maintained that the universities gave a student, for his tuition, “more than he would receive from a proprietary school, because the university’s main aspiration is to give as much as possible on a basis of public responsibility” (p. 524). He concluded his talk by appealing to orthodontists to “follow impulses and leaderships that represent… the finest that is in you individually and professionally” (p. 525).

The 1930s

Discussion in the 1930s focused on the type of education that would be most effective. Early in 1930, Richard Summa from St Louis questioned why orthodontic postgraduate education had to be extended over a year or more, and he disagreed with those who thought that general dentists could not handle the information. He felt that “the value of each branch (of medical science) is measured by its success and availability… . [N]o phase of orthodontia is beyond the comprehension of any graduate dentist.”

One primary reason for extending the length of orthodontic education was to enable students to treat patients longitudinally. Summa stated, “the clinical phase of orthodontic instruction is the difficult problem confronting schools and is insurmountable if it be required that students treat and observe cases from beginning to end.” He postulated that it would be impossible for anyone, instructor or student, to ever see and treat all possible variations of malocclusion during his or her lifetime, so that orthodontic instruction by necessity must be “typal.” Summa recommended that short courses similar to the Angle School should be held at universities, and that the school should “carry” patients who are treated in an ongoing fashion, with students observing them during short courses.

Later that year, T.W. Sorrels wrote from Oklahoma about the increase in dental disease and malocclusion in the general public, and the inability of orthodontists to serve the public. Contrary to Summa, however, he thought that dentistry had become so complex that it was impossible for any one person to “expertly” practice all aspects. He noted that oral surgery and orthodontics were recognized as specialties and that pediatric dentistry, periodontia, and prosthodontia were gaining recognition as such. Sorrels believed that “the obligation of the universities to provide a systematic curriculum for the training of specialists in orthodontia… is clear and urgent” (p. 797) and that in all but 4 schools, proper courses were not being provided.

Sorrels thought that both universities and the public (through government funding) should assist in the training of orthodontists, and he proposed some changes that could be made to make sure that more patients were served. Although predoctoral education at that time was 5 years, he suggested lengthening each year from 9 to 11 months so that the curriculum could be accommodated in 4 longer years. Predoctoral students could major in orthodontics to determine their aptitude for the subject and then continue on for an optional full year of graduate studies in orthodontics. This additional year would culminate in a master’s degree, and a second year would be available for further studies, research, and a doctoral degree. He suggested that opportunities could be provided for others to enter the specialty by offering this course in sections.

The issue was apparently not solved by 1936 when Spencer R. Atkinson ( Fig 2 ) and David W. McLean added their views on what education was needed. They observed that although orthodontics was becoming more complex, with additional considerations given to endocrine and metabolic disturbances, masticatory function, and the relationship between malocclusion and periodontal disease, there was a trend toward “simplifying and cheapening” (p. 209) orthodontic services. They explained that there were 2 kinds of simplicity: that of efficiency, and that of ignoring details and compromising ideals. The bulk of their article detailed situations in which faulty posture, endocrine disturbances, faulty swallowing, occlusal abnormalities, and muscle pressure posed problems that the orthodontist needed to address. They concluded that these additional issues needed to be included in the orthodontic curriculum to optimize results and prevent relapse. Consequently, they observed that a mere technique class of 8 to 10 weeks would not be enough to fully educate orthodontists, since orthodontics was no longer simply tooth movement. They stated, “The day of the private orthodontic school is past. Orthodontic education must be carried on in universities where… the knowledge contained in various scientific departments of a university can be pooled, correlated, and applied to the orthodontic problem” (p. 217).

Two years later, H.C. Pollock ( Fig 3 ) wrote an editorial on the subject of orthodontic education. He observed that 40 years earlier there had been no specialty of orthodontics, but presently, although orthodontics was a well-recognized specialty, there was still no single method of training to be an orthodontist. He acknowledged that many would still recommend observing in a private office for some months, in addition to taking a practical course at a university. Pollock noted that orthodontists were often accused of being indifferent to the public welfare and of discouraging others to become orthodontists, but he theorized that this was not out of selfishness but was because there was no good method for education. University dental schools, for the most part, were not equipped for postgraduate education, since they had a difficult time recruiting excellent faculty because of financial pressures. He directed responsibility for these problems at the universities and hoped that a university with sufficient resources, in terms of both finances and faculty, would “save orthodontics from its present role as the stepchild of dentistry” (p. 403).

William J. Gies, a biochemist from Columbia University, had gained recognition in the dental community for his comprehensive, 250-page report on dental education that established the importance of dentistry in health care and stressed the role of universities in dental education. At a meeting of the New York Society of Orthodontists in 1938, he spoke about the need for the involvement of universities in educating orthodontists. He compared the education at proprietary orthodontic schools and universities, and while he acknowledged that some proprietary schools “stimulated and sustained the development of orthodontics” (p. 524), he maintained that universities should be preferred because most proprietary schools had a dominant profit motive. He maintained that the universities gave a student, for his tuition, “more than he would receive from a proprietary school, because the university’s main aspiration is to give as much as possible on a basis of public responsibility” (p. 524). He concluded his talk by appealing to orthodontists to “follow impulses and leaderships that represent… the finest that is in you individually and professionally” (p. 525).

The 1940s

The discussion as to how orthodontics should be taught persisted into the next decade. In 1942, Leuman Waugh and his colleagues from Columbia University (Drs Dunning, Hoyt, Merritt, Newman, Walker, and Gies) published a comprehensive proposal for orthodontic education that encompassed predoctoral and postdoctoral education, university extension and graduate programs, and specialty licensure. They discussed several types of predoctoral instruction, from those with clinical requirements in orthodontics to those that stressed fundamental sciences with and without laboratory requirements. Because of the difficulty of including enough orthodontics in the predoctoral curriculum for a graduate dentist to become competent in clinical orthodontics, and owing to interest expressed in only 6% to 14% of the dental students surveyed, Waugh and his colleagues did not think that clinical requirements were necessary but, likewise, did not believe that the general dentist should have no familiarity with orthodontic appliances. They consequently proposed that dentists should know how to repair and remove appliances as necessary and suggested 110 hours of instruction during dental school, including a didactic course, a demonstration clinical course, a laboratory technique course, and an elective clinical course.

The proposed graduate program was intended to lead to a graduate degree when appropriate but included clinical work that would merit a certificate of proficiency. They suggested that this education regimen would require 14 months of full-time study or 26 months of half-time study, including vacations. An original thesis would also be required. The authors strongly felt that less than half-time effort greatly diluted the “seriousness” of the course and should not be eligible for university credit. In general, Waugh and his associates recommended that full-time graduate study would be necessary for orthodontic specialty education.

John W. Ross reiterated other authors’ conclusions regarding orthodontic education in his thesis for his American Board of Orthodontics (ABO) certification, which reviewed at length the history of orthodontic education to date. He pointed out that although it would be possible to include enough information to adequately educate dental students in orthodontics, doing so would either crowd operative and prosthetic dentistry out of the curriculum or require an additional year. He further stated that even though most state boards did not examine the new dental graduate in orthodontics, and although most universities gave short shrift to predoctoral instruction, general dentists were allowed to practice orthodontics. Ross consequently thought that orthodontic education should be offered as a 1-year graduate program leading to a certificate, with a master’s degree available with further research time.

However, university education was not seen to be without problems. Ross noted that in 1948 there was no consensus (and great debate) about whether extraction must never be practiced or always practiced. There was likewise no agreement about the amount of force to be used in tooth movement. There was no surprise then that proprietary schools, which typically taught the methods of their founders, were still competing with university programs. Ross stressed that orthodontic education needed to be based on a scientific foundation of evidence in anatomy, embryology, physiology, biomechanics, and child psychology. He called for increased research to answer some of the questions raised by clinical problems. Finally, he concluded by warning that “Orthodontics is a needed health service and the public must be served. Unless the standards of orthodontic practice are raised, the public will suffer” (p. 263).

That same year, the Committee on Education of the American Association of Orthodontists (AAO) published a report on orthodontic education it had written to the association’s Board of Directors. The report recommended a full-time, 15-month course comprising 2300 calendar hours over 65 weeks that led to a certificate for a master’s degree. Although the committee acknowledged that the American Dental Association recommended 2 academic years, it pointed out that its proposal was better because “continuous” time was better for patient care, and consequently the proposed program would not take so much time. The committee also repeated earlier conclusions regarding predoctoral education, saying that the undergraduate dentist could not get enough orthodontic instruction without displacing other areas of dentistry or adding an additional year, and it recommended that predoctoral education should focus on prevention of malocclusion, growth and development, and interceptive procedures.

The following year, M. Albert Munblatt from New York published a response to the report of the Committee on Education. Munblatt elaborated on the controversy in orthodontic education and the tension between predoctoral and graduate education. He explained that many areas of debate were due to the development of factions of thought in orthodontics because of the proprietary schools and pointed out that although there are differences of opinion in any science, they can be dangerous. He cautioned that orthodontics must be able to discriminate between pseudoscience and science. He stated, however, that in any biologic science there is considerable human variation, so there is often not one answer for orthodontic problems. He concluded by recommending that predoctoral dental education should include the basic and correlated subjects of orthodontic science as didactic courses, and that the dental student should observe and assist in the graduate clinic, but that the “proper” training of an orthodontist must take place in the context of graduate and postgraduate education. He discouraged short and intensive courses in orthodontics.

The president of the ABO, B.G. deVries, wrote a treatise to explain the position of the ABO in regard to orthodontic education, seemingly in response to criticism about its stance on educational requirements. The ABO had no educators on its board and wanted to remain outside the realm of dental school influence. DeVries explained that the board “should not assume the responsibilities of other groups whose purpose it is to prepare applicants for examination” (p. 290) but maintain flexibility in the amount of education required. Because not every ABO applicant had the opportunity to attend a graduate school of orthodontics, the ABO simply required 5 years of exclusive practice of orthodontics. DeVries defended this seemingly contrary requirement by stating that “an impressive number of degrees does not necessarily mean that the holder is a competent practicing orthodontist… . The Board feels that we should preserve the right of an individual to apply for certification without having to wait or defer to the slow processes of establishing curricular changes and the provision of adequate educational facilities” (p. 291). In closing, deVries stated that the ABO was fulfilling its mission as directed by the AAO, and that as educational institutions raised the standards of orthodontic education, the ABO might well change its eligibility requirements as well.

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses