Many patients with hypertension have uncontrolled disease. The dental visit presents a unique opportunity to screen patients for undiagnosed and undertreated hypertension, which may lead to improved monitoring and treatment. Although there are no clinical studies, it is generally recommended that nonemergent procedures be avoided in patients with a blood pressure of greater than 180/110 mm Hg. Because of the high prevalence of disease and medication use for hypertension, dentists should be aware of the oral side effects of antihypertensive medications as well as the cardiovascular effects of medications commonly used during dental visits.

- •

Many patients with hypertension have uncontrolled disease. The dental visit presents a unique opportunity to screen patients for undiagnosed and undertreated hypertension, which may lead to improved monitoring and treatment.

- •

Although there are no clinical studies, it is generally recommended that nonemergent procedures be avoided in patients with a blood pressure of greater than 180/110 mm Hg.

- •

Because of the high prevalence of disease and medication use for hypertension, dentists should be aware of the oral side effects of antihypertensive medications as well as the cardiovascular effects of medications commonly used during dental visits.

Hypertension: definition, importance, and benefits of treatment

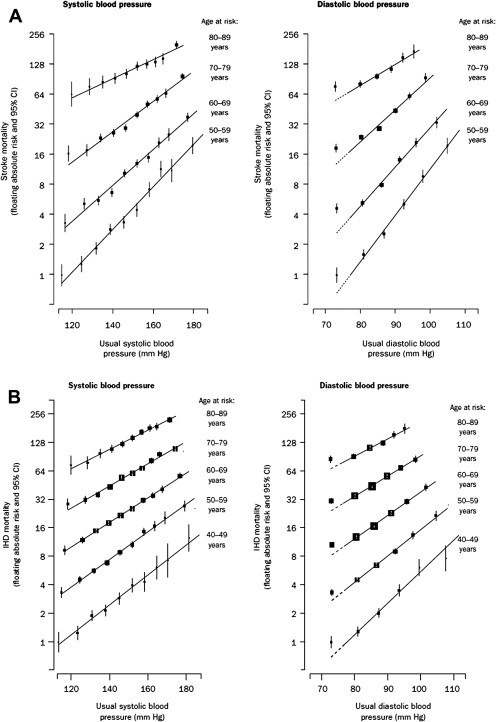

The most commonly referenced guideline pertaining to blood pressure in adults in the United Sates is the Seventh Report of the Joint National Committee on the Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure (JNC 7), which was published in 2003. JNC 7 defines hypertension as a systolic blood pressure (SBP) greater than 140 mm Hg or a diastolic blood pressure (DBP) greater than 90 mm Hg. These definitions are derived from studies showing increased adverse cardiovascular outcomes in patients with blood pressure above these levels. A meta-analysis demonstrated that for each 20 mm Hg increase of SBP above 115 mm Hg and 10 mm Hg of DBP 75 mm Hg in patients 40 to 70 years of age, the risk of death from cardiovascular events (stroke, myocardial infarction) doubles ( Fig. 1 ). JNC 7 also introduced the category of Prehypertension, which is defined as an SBP of 120 to 139 mm Hg and DBP of 80 to 89 mm Hg ( Table 1 ). These individuals are at increased risk of developing hypertension.

| Classification | SBP (mm Hg) | DBP (mm Hg) |

|---|---|---|

| Normal | <120 | And <80 |

| Prehypertension | 120–139 | Or 80–89 |

| Stage I hypertension | 140–159 | Or 90–99 |

| Stage II hypertension | ≥160 | Or ≥100 |

Treating hypertensive patients with lifestyle modification and medications has been associated with reductions in adverse cardiovascular outcomes. One meta-analysis showed a reduction of stroke by 30% to 39%, major cardiovascular events by 20% to 28%, and heart failure by more than 50% with the use of medications such as angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (ACEIs) and calcium-channel blockers. Physicians aim to achieve a goal blood pressure that is dependent on the patient’s age and additional medical problems, if present.

Epidemiology

As of the publication of the JNC 7 report, an estimated 50 million Americans had hypertension, making it the most commonly diagnosed medical condition in the United States. JNC 7 estimated that 1 billion people worldwide have hypertension. Furthermore, 30% of patients with hypertension were unaware that they had the condition, 41% were not being treated for their disease, and only 34% of patients had reached a goal blood pressure of less than 140/90 mm Hg. Screening for hypertension during dental visits, therefore, is an opportunity to increase hypertensive patients’ awareness of their disease, as well as to improve medical referral for initiation or modification of treatment.

Epidemiology

As of the publication of the JNC 7 report, an estimated 50 million Americans had hypertension, making it the most commonly diagnosed medical condition in the United States. JNC 7 estimated that 1 billion people worldwide have hypertension. Furthermore, 30% of patients with hypertension were unaware that they had the condition, 41% were not being treated for their disease, and only 34% of patients had reached a goal blood pressure of less than 140/90 mm Hg. Screening for hypertension during dental visits, therefore, is an opportunity to increase hypertensive patients’ awareness of their disease, as well as to improve medical referral for initiation or modification of treatment.

Measurement of blood pressure

The gold standard for measurement of blood pressure is via an intra-arterial catheter. However, this is an invasive and impractical method to measure blood pressure in outpatients. The most common methods used to evaluate blood pressure are office blood pressure measurement, home blood pressure measurement (whereby a patient measures his/her blood pressure at home with a blood pressure machine), and ambulatory blood pressure measurement (whereby a patient’s blood pressure is measured at intervals over a 24-hour period to calculate averages in SBP and DBP). A dentist’s role in measuring blood pressure will likely be limited to office blood pressure measurements.

JNC 7 includes a description of the method that health care professionals should use to obtain office blood pressure measurements. One must use a properly calibrated and validated blood pressure instrument. Patients should be seated in a chair (not an examination table) with their feet on the floor for 5 minutes in a quiet room. Their arm should be supported at the level of the heart and an appropriately sized blood pressure cuff (cuff bladder encircling at least 80% of the arm) must be used. Accurate measurement of blood pressure is important to avoid overdiagnosis and underdiagnosis, as well as overtreatment and undertreatment, of hypertension. Although the use of noninvasive blood pressure measurements does lead to discrepancies compared with intra-arterial catheter measurement, most large trials that have studied hypertension-related outcomes have been performed with the noninvasive technique, and it is currently still widely relied on.

White-coat hypertension, the white-coat effect, and masked hypertension

White-coat hypertension (WCH) refers to a persistently elevated office blood pressure in the presence of a normal blood pressure outside of the office. WCH is different from the white-coat effect (WCE), which refers to a high office blood pressure but whereby hypertension may or may not be present outside the office setting. Masked hypertension refers to when a patient has a normal office blood pressure but has hypertension outside of the office ( Table 2 ). WCH, the WCE, and masked hypertension can be diagnosed through various methods including home blood pressure monitoring and 24-hour ambulatory blood pressure monitoring. WCH and masked hypertension are important for clinicians to recognize. It is controversial as to whether WCH is associated with increased cardiovascular risk, but patients with masked hypertension are at increased cardiovascular risk. The prevalence of WHC during physician visits is approximately 20%. The prevalence of WCH in the setting of visits to the dentist’s office has not been established.

| Diagnosis | Office Blood Pressure | Blood Pressure Outside Office | Associated with Adverse Outcomes? |

|---|---|---|---|

| WCH | Elevated | Normal | Controversial |

| WCE | Elevated | Normal or High | Controversial |

| Masked hypertension | Normal | Elevated | Yes |

Pathophysiologic mechanisms and treatment strategies for hypertension

It is important to first recognize that a subset of patients with elevated blood pressure will have secondary hypertension: hypertension that has an identifiable medical cause which, if corrected, will result in the resolution of high blood pressure. These causes include primary hyperaldosteronism, Cushing disease, coarctation of the aorta, pheochromocytoma, and renovascular hypertension. Ninety-five percent of patients, however, will have no identifiable cause for their hypertension; this is called essential hypertension and is the focus of the remainder of this section.

Essential hypertension has been shown to have many pathophysiological causes ( Table 3 ). Three important causes are salt/volume overload, activation of the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system (RAAS), and activation of the sympathetic nervous system. It is important that this physiology is understood, because most current pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic treatment is based on targeting these mechanisms.

| Mechanism | Medications Targeting this Mechanism (Examples) |

|---|---|

| Volume overload | Diuretics (hydrochlorothiazide, chlorthalidone, metolazone, furosemide, torsemide) Dihydropyridine CCBs (amlodipine, nifedipine) |

| Renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system | ACEIs (lisinopril, captopril) ARBs (losartan, valsartan) β-Blockers (metoprolol, carvedilol) Direct renin inhibitors (aliskerin) Aldosterone receptor blockers (spironolactone, eplerenone) |

| Sympathetic nervous system | Central α-blockers (clonidine) Peripheral α-blockers (tamsulosin, terazosin) β-Blockers (metoprolol, carvedilol) Nondihydropyridine CCBs (verapamil, diltiazem) Vasodilators (minoxidil, hydralazine, nitrates) |

Salt/Volume Overload

Salt (sodium chloride) overload/volume overload is one mechanism that commonly contributes to essential hypertension. High sodium intake has been associated with essential hypertension in a variety of scientific models and clinical studies, and decreasing the sodium intake ameliorates this effect. High sodium intake increases blood pressure by expanding intravascular volume, and may have direct neurohormonal effects on the cardiovascular system. Such salt-sensitive patients benefit from the following interventions:

- •

A low sodium diet (less than 2.4 g of sodium per day) or the DASH diet (Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension), which is low in sodium and higher in other elements such as potassium and calcium.

- •

Diuretics, which are medications that increase urinary sodium excretion by blocking reabsorption of sodium in the kidney. Commonly used medications include loop diuretics (such as furosemide, bumetanide, and torsemide), thiazide and thiazide-like diuretics (such as hydrochlorothiazide, chlorthalidone, and metolazone), and aldosterone-receptor blockers (such as spironolactone and eplerenone). These classes of diuretics differ in their sites of action within the nephron.

- •

Calcium-channel blockers, which include dihydropyridines (peripheral-acting medications such as nifedipine and amlodipine) and nondihydropyridines (central-acting medications such as verapamil and diltiazem), which are vasodilators and have negative effects on cardiac output, and also are effective in patients with sodium and volume overload.

Renin-Angiotensin-Aldosterone System

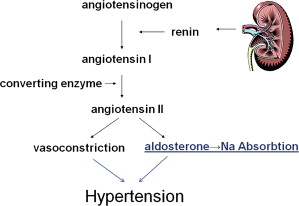

The RAAS hormonal axis also contributes to hypertension in many patients. Renin, a hormone synthesized and released by the kidney in response to intravascular volume depletion and hyperkalemia, promotes the conversion of angiotensinogen (produced by the liver) to angiotensin I. Angiotensin I is then converted to angiotensin II by the angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) in the lung. Angiotensin II increases blood pressure by increasing renal sodium reabsorption, producing vasoconstriction, and activating the sympathetic nervous system (see later discussion). Angiotensin II also increases the production and secretion of aldosterone from the adrenal cortex. Aldosterone also increases renal sodium reabsorption. Thus, the RAAS system increases blood pressure through increasing renal sodium reabsorption (which leads to intravascular volume expansion) and vasoconstriction ( Fig. 2 ).

The RAAS is activated in many patients with essential hypertension and other associated conditions such as obesity and sleep apnea. In addition to treating these underlying diseases, medications are used to block various components of the RAAS pathway.

- •

β-Blockers such as propranolol, carvedilol, and metoprolol decrease renal renin release.

- •

The direct renin inhibitor aliskiren binds to renin and thus prevents the conversion of angiotensinogen to angiotensin I.

- •

ACEIs block ACE and therefore prevent the conversion of angiotensin I to angiotensin II.

- •

Angiotensin II receptor blockers (ARBs) prevent angiotensin II from binding to its receptor, decreasing vasoconstriction and renal sodium reabsorption.

- •

Aldosterone-receptor blockers (such as spironolactone and eplerenone) and other medications such as amiloride decrease the effects of aldosterone-mediated renal sodium reabsorption.

Sympathetic Nervous System

Activation of the sympathetic nervous system (SNS) also contributes to the development, maintenance, and progression of hypertension. There are many, incompletely understood mechanisms by which SNS activation leads to hypertension. SNS activation is present in many disease states such as obesity, obstructive sleep apnea, and alcoholism, and therapies have been developed to target the central, peripheral, and renal SNS to improve the control of blood pressure.

Therapies to improve blood pressure in these patients include:

- •

Treatment of underlying contributing conditions through weight loss, treatment of sleep apnea, and avoidance of alcohol, respectively

- •

Medications that mitigate the actions of an activated SNS such as peripheral α1-receptor blockers (such as terazosin and tamsulosin), the central α2-agonist clonidine, and β-blockers

- •

Other vasodilatory medications such as minoxidil, nitrates, and hydralazine

- •

Surgical renal sympathetic denervation, used with success in some patients with resistant hypertension

Screening for hypertension during dental visits

The dental visit provides an opportunity to screen large percentages of the population for hypertension. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) estimated that 65.4% of Americans older than 2 years had at least one dental visit in 2009. Sproat and colleagues noted that 59% of the population attends annual dental appointments in the United Kingdom, and Jontel and Glick reported that 95% of the population in Sweden between the ages of 30 and 64 had used the Swedish dental health system within 5 years.

Screening for hypertension at dental office visits has been explored in multiple studies. Fernandez-Feijoo and colleagues screened 154 patients who presented for a dental checkup in Spain over a 6-month period in 2008. Forty-five of 154 (29.2%) patients had an SBP greater than 140 mm Hg and/or a DBP greater than 90 mm Hg, 33 of whom did not carry a diagnosis of hypertension before that visit. After referral to a physician, this screening resulted in 18 patients starting pharmacologic or nonpharmacologic therapy for hypertension.

Sproat and colleagues screened patients older than 18 years for hypertension over a 3-day period at a dental practice in the United Kingdom, and found 44 of 144 (39%) of patients to have an SBP greater than 140 mm Hg and/or a DBP greater than 90 mm Hg. Thirty-six of these 44 patients (82%) had not been diagnosed with hypertension previously, and this increased blood pressure was not associated with increased anxiety as measured by the Dental Anxiety Scale (DAS).

Jontel and Glick screened 200 patients with visits at 10 dental practices in Sweden for hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and hyperglycemia, and used the HeartScore scale to determine their cardiovascular risk. Twelve of 200 patients (6%) had a greater than 10% risk of a fatal cardiovascular event in the next 10 years based on this screening, ultimately resulting in 7 patients being treated medically for hypertension or hyperlipidemia.

Glick and colleagues extracted data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) database. These investigators examined patients aged 45 to 85 years with no specific risk factor for coronary heart disease, who had seen a dentist in the last year but who had not seen a physician during that time. Eighteen percent of males in this population had a >10% Framingham risk for experiencing a coronary heart disease event within 10 years.

These studies demonstrate that screening for hypertension at dental visits allows for the identification of patients with previously undiagnosed hypertension, poorly controlled hypertension, and patients at increased risk for cardiovascular events. It is because of this opportunity and the relative ease of conducting blood pressure screening that many experts have agreed with the JNC 7 in recommending screening for hypertension at dental office visits. Measurement of blood pressure should be done in the dental office at regular intervals.

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses