and Paolo Biondi2

(1)

Aesthetic and Maxillofacial Surgery, Padova, Italy

(2)

Maxillofacial Surgery, Forlì, Italy

10.6.1 General Considerations

10.7.1 Forehead Transverse Furrows

10.7.2 Frown Lines

10.7.3 Temporal Depression

10.7.4 Eyebrow Ptosis

10.7.5 Upper Eyelid Hooding

10.7.7 Lateral Canthal Bowing

10.7.8 Scleral Show

10.7.9 Baggy Lower Eyelid

10.7.12 Nasolabial Fold

10.7.13 Preauricular Lines

10.7.14 Lip Lines

10.7.15 Horizontal Upper Lip Line

10.7.18 Jowls and Prejowl Depression

10.7.21 Horizontal Neck Lines

10.7.22 Ptotic Submandibular Gland

10.11.2 Other Terms

Abstract

The causes almost always start to act early on the facial tissue, but the consequences are manifest only over the long term. This reminds us of many of the great problems that humans are incapable of solving, such as wars, the hole in the ozone layer, the big fi nancial crises, environmental pollution, and many others. In all cases, nobody recognizes himself as being guilty because our single action is so small and so distant in time and space that we have completely lost the connections when the problem arises in its full extent.

We have met the enemy…… and he is us!– Walt Kelly (cited in [7])

The “process of aging” is the sum of factors acting on all the four main components involved in facial aesthetics:

-

The soft tissue quality

-

The soft tissue quantity

-

The soft tissue dynamics

-

The supporting bony, dental, and cartilaginous skeleton

The causes almost always start to act early on the facial tissue, but the consequences are manifest only over the long term. This reminds us of many of the great problems that humans are incapable of solving, such as wars, the hole in the ozone layer, the big financial crises, environmental pollution, and many others. In all cases, nobody recognizes himself as being guilty because our single action is so small and so distant in time and space that we have completely lost the connections when the problem arises in its full extent.

So, one of the difficult tasks in facial analysis is the early detection of the signs of aging in the younger patient, as well as the identification of the basic developmental deformities that worsen the final effects of aging. In other words, we must observe the young subjects now, also thinking in terms of future aging.

10.1 Structural Factors of Aging

When a young or middle-aged subject appears “aged,” the presence of one or more structural factors of aging should be suspected, looked for, and assessed. For example, the association of two structural factors, one affecting the soft tissue, such as a vertically long upper lip, and another affecting the dental and skeletal framework, such as a vertical short maxilla, can produce an aged appearance affecting all the lower facial third. This negative combination also influences the act of smiling of the patient as a result of the reduced exposure of the upper anterior teeth (Fig. 10.1).1

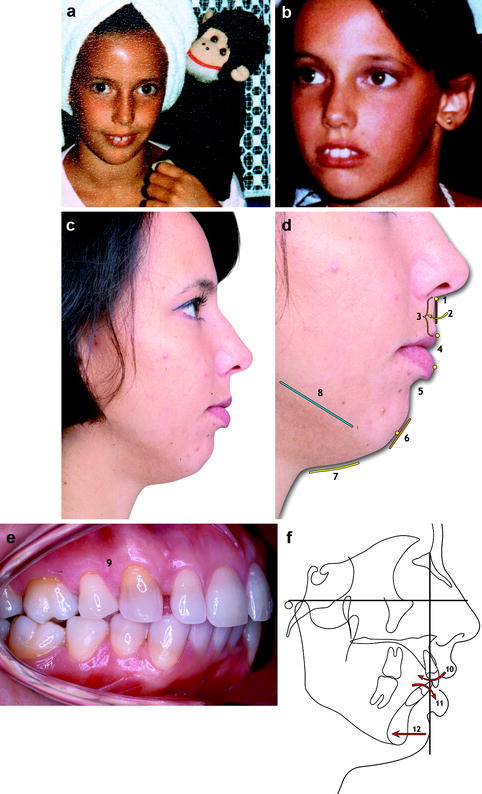

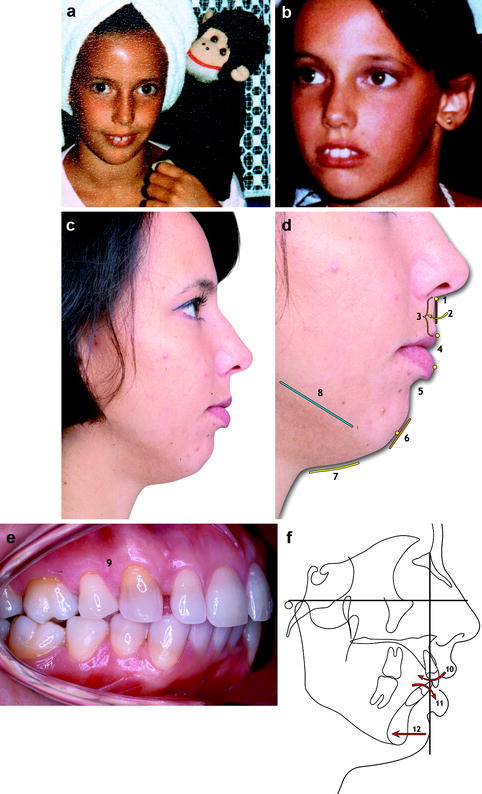

Fig. 10.1

In this 40-year-old woman, a structural vertically long upper lip is associated with a vertically short maxilla. Both are responsible for a prematurely aging appearance (a, b). A close analysis of the perioral region in profile view (c) permits us to point out some conclusions: (1) the skin portion of the upper lip is too long; (2) the upper lip is excessively clockwise rotated; (3) the upper vermillion portion of the upper lip is hidden to the observer; (4) the entire lip outline is poorly supported and lies too posterior with respect to the E-line (a reference line connecting the tip of the nose to the most anterior point of the chin contour). The prematurely aging appearance is confirmed during smiling as a result of her inability to obtain a normal display of the anterior upper teeth and gingiva (d, e)

Sometimes the structural factors of aging are not easily detected because of the compensation offered by the soft tissue envelope, which, in a young subject, has an important role of camouflage. A typical example is the effects of teeth extraction, performed in childhood for orthodontic needs, as in the clinical case of the young girl reported in Fig. 10.2. Before the orthodontic treatment, the main concern of her parents was the protruding anterior teeth; her dentist “solved” the problem by extracting an upper premolar on each side and retracting the upper incisors but left untreated (or misdiagnosed) the mandibular deficiency. When her case was documented, at the age of 26 years, the initial signs of aging on the upper lip were evident and will worsen in the future when the camouflage effects produced by the soft tissue envelope progressively disappear.

Fig. 10.2

In the two childhood photographs, taken from the personal album of the patient, clear protruding upper incisors were seen (a, b). When she was 26 years old, a complete facial analysis including the dental arches and cephalometric tracing (c–f) highlighted: 1 moderate vertical lengthening of the upper lip, 2 clockwise rotation of the upper lip outline, 3 flattening of the upper lip contour when the patient maintained the lip seal, 4 discrepancies between the vermillion exposure of the upper and lower lip, 5 excessive lower lip eversion, 6 flattening of the chin contour due to the muscular strain necessary to maintain the lip seal, 7 reduction of the throat length, 8 absence of definition of the mandibular border, 9 absence of one upper premolar on each side, 10 clockwise rotation of the upper incisors, 11 counterclockwise rotation of the lower incisors, and 12 a noticeable retrusion of the mandible

This case confirms the initial assertion that if our actions, i.e., the teeth extraction and orthodontic treatment, are so distant in time and space, we, and our patients too, lose the connections between cause and effect when the problem of aging arises in its full magnitude. To prevent the aesthetic problem of this dentofacial deformity as well as confronting the aging process, a different treatment should have been done when she was in her teens:

-

Avoid the extraction of the upper premolars.

-

Extract one inferior premolar on each side.

-

Retract the inferior anterior teeth with orthodontics.

-

Perform the surgical advancement of the mandible to correct the sagittal component of the malocclusion as well as the facial profile.

10.2 Soft Tissue Quality and Aging

Aging acts by changing the skin through two distinct basic processes: intrinsic and extrinsic. Intrinsic aging is inevitable, not beyond voluntary control, and reflects the genetic background of the subject. Extrinsic aging is mainly caused by sun exposure but also by smoking, excessive use of alcohol, and poor nutrition, so in some ways, it can be prevented [1] (see Sect. 13.14).

In clinical facial analysis, but also when communicating with the patient, it is imperative to differentiate between the quality of the skin, which consists of the skin color, texture, tone, elasticity, pigmented lesions, and the quantity and displacement of skin and other facial soft tissue (see also Sect. 5.5).

10.3 Soft Tissue Quantity and Aging

Aging also acts by reducing volumes, enlarging the surface, and displacing facial soft tissue. A process of atrophy (dermal atrophy, muscle atrophy, connective atrophy, fat atrophy) is responsible for volume reduction. A process of skin and connective tissue elongation, real or relative, is responsible for redundancy, “bag” formation, and ptosis. The interaction between the two previous processes also permits the displacing, in the vertical direction, of intraorbital, malar, facial, and neck fat. The same displacement can also affect the lacrimal and submandibular glands.

Some facial convexities become flat with aging, such as the cheeks and lips, and some flat areas bulge, such as the lower lid and submental.

10.4 Soft Tissue Dynamics and Aging

Muscular activity can produce evident skin creases and, at the same time, can hold up some skin areas, as happens with the eyebrow, giving the false impression that its position is correct. When analyzing the face, a special effort is made by the observer to envision the direction of underlying mimetic muscles and correlate it to external visible effects.

10.5 Skeletal Supporting Framework and Aging

A preexisting dentofacial deformity can aggravate and anticipate the aged look. If a patient looks older, check on the personal patient photographs searching for any preexisting aging signs and for the general features of the facial skeleton. The lack of support can be localized or extended over more subunits of the face, affecting the bone, cartilaginous, and dental framework.

10.6 Recognizing Aging in the Face

10.6.1 General Considerations

A comparison between youthful and aged faces reveals one or more of these changes:

-

The general face form becomes longer and narrower. It can also shift from a triangular to a rectangular shape.

-

Some subunits become empty and others become full.

-

Some profile curves flatten.

-

Some new curves appear.

-

Some profile segments elongate.

10.7 Recognizing the Signs of Facial Aging

Some signs of aging are absent in a youthful face, such as the platysma bands, whereas others are already present in young subjects and their change, as when the nasolabial line transforms into the nasolabial groove and fold, underlines the progress of the aging.

Instead of discussing the theories of facial aging in depth (see Sect. 13.15), a list of the clinical signs of aging, from forehead to neck, is presented with some relevant specific considerations.

10.7.1 Forehead Transverse Furrows

The horizontal forehead furrows are usually two or three, continuous or centrally interrupted, lines. They are secondary to chronic frontalis muscle contraction produced as an effort to raise the descended eyebrows. As with any other mimetic wrinkle, line or furrow, the forehead transverse furrows are perpendicularly oriented to the underlying muscular fibers (Fig. 10.3).2

Fig. 10.3

Forehead and worry lines in a 65-year-old woman. These lines are all secondary to chronic muscular contraction of the frontalis muscle (1 forehead lines), corrugator muscle (2 paired vertical worry lines), and procerus muscle (3 single horizontal worry line)

10.7.2 Frown Lines

The frown lines can be divided into vertical and horizontal. The vertical frown lines occupy the glabella, usually one for each side, and are perpendicular to the orientation of the fibers of the corrugator muscle, whereas the horizontal frown line is typically a single line occupying the radix of the nose and is perpendicular to the orientation of the fibers of the procerus muscle (Fig. 10.3). Each is considered to be a mimetic line.

10.7.3 Temporal Depression

The facial aging process can be seen in some areas as a progressive volume reduction of soft tissue, producing the effect called skeletonization, whereas in others, the soft tissue progressively increases or is made redundant, producing the opposite effect of hiding the skeletal and muscular contour. The temporal region usually undergoes a gradual loss of volume, producing a depression that is responsible for highlighting its skeletal boundaries: the zygomatic arch, the lateral orbital rim, and the temporal crest (Fig. 10.4).

Fig. 10.4

Low-grade temporal depression in a 65-year-old woman. The skeletal boundaries of the temporal region are highlighted

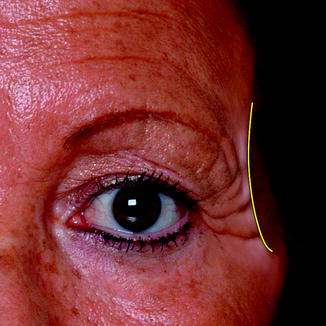

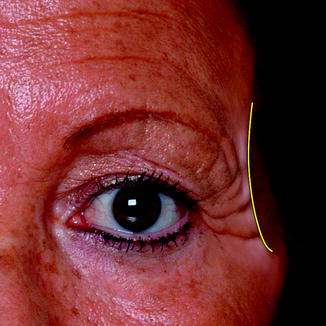

10.7.4 Eyebrow Ptosis

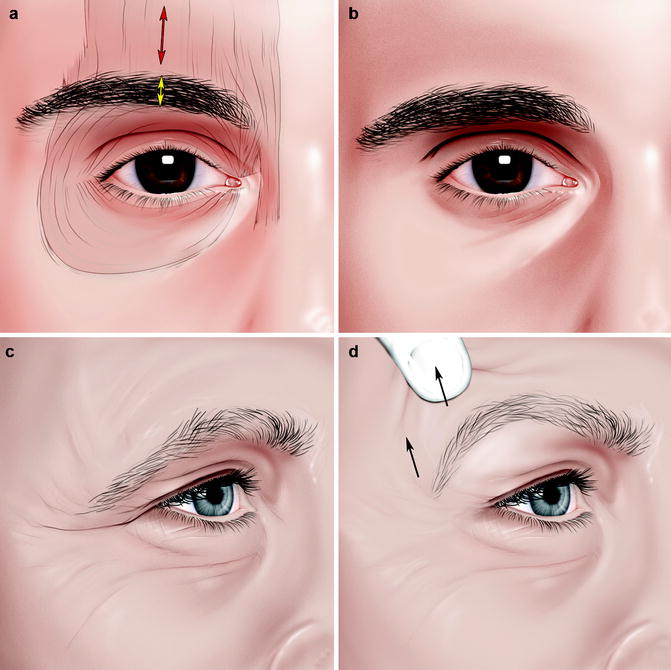

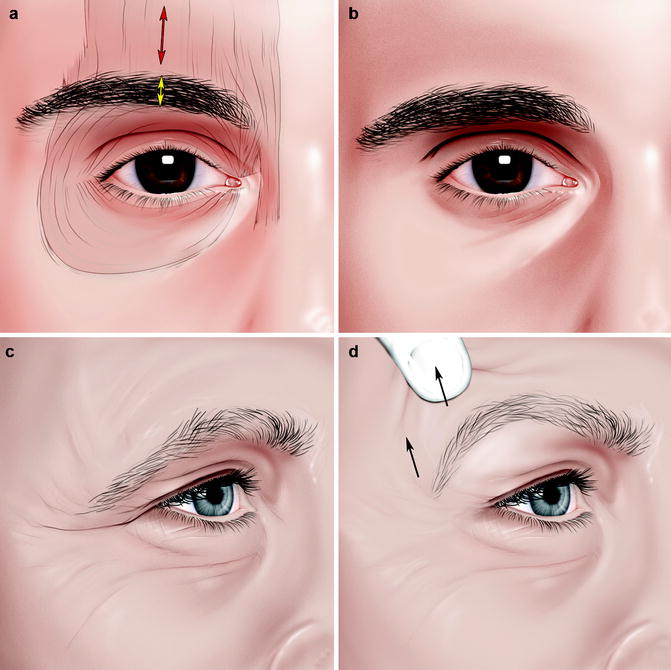

Detecting eyebrow ptosis is not so easy because of the contraction of the frontalis muscle, which produces some degree of “balancing” elevation, as well as confusing the brow ptosis as a unique problem of hooded upper eyelid skin (Fig. 10.5a).

Fig. 10.5

The vertical position of the eyebrow is dynamically related to the activity of the frontalis muscle (a). A horizontal shadow at the level of the upper eyelid gives the illusion that the eyebrow is more ptotic than it really is (b). A lateral extension over the eyelid and onto the lateral periorbital region of the upper lid crease, or Connell’s sign, is a hallmark of forehead ptosis (c). The correct vertical position of the eyebrow can be envisioned during the consultation, utilizing Flower’s maneuver, by holding up the eyebrow with a fingertip (d)

The eyebrow, as with many other facial structures, is a moving target! So, after the correction of a ptotic upper marginal lid, the frontalis muscle contraction reduces with a downward repositioning of the eyebrow, which is now clearly ptotic to the examiner and patient.

Another problem lies in the illusional effect produced by a deep upper palpebral fold and/or prominent upper orbital margin. The resulting horizontal shadow makes the eyebrow “more ptotic” even if it is in the same vertical position. The loss of upper palpebral volume, either to a progressive involution or secondary to aggressive surgical treatment, creates a skeletonized orbit that is also responsible for this shadow (Fig. 10.5b).

In eyebrow analysis, it is important to detect a lateral extension over the eyelid and onto the lateral periorbital region of the upper lid crease or Connell’s sign (reported also in Chap. 6), which is a hallmark of forehead ptosis (Fig. 10.5c). The correct vertical position of the eyebrow can be envisioned during the consultation, utilizing Flower’s maneuver, by holding up the eyebrow with a fingertip [5] (Fig. 10.5d).

10.7.5 Upper Eyelid Hooding

The attenuation of the orbicularis oculi muscle and orbital septum, the orbital fat pad pseudoherniation, as well as the progressive gravitational descent of the forehead skin and upper lid laxity, can produce upper eyelid hooding, which is usually more pronounced in the lateral aspect (Fig. 10.6

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses