Intrinsic pain of the masticatory muscles is sometimes perceived by oral and maxillofacial surgeons as a vaguely defined syndrome managed by somewhat mysterious—but definitely nonsurgical—treatment. In fact, myogenous temporomandibular disorders (TMDs), or masticatory myalgias, are characterized by pain and dysfunction arising from a number of well-defined, distinct pathologic and functional processes in the masticatory muscles. These include myofascial pain (MFP), myositis, muscle spasm, and muscle contracture. The surgeon who would operate on the temporomandibular joint (TMJ) must also be familiar with the diagnosis and nonsurgical management of these muscular problems. This chapter defines these disorders and suggests effective and evidence-based therapies for each.

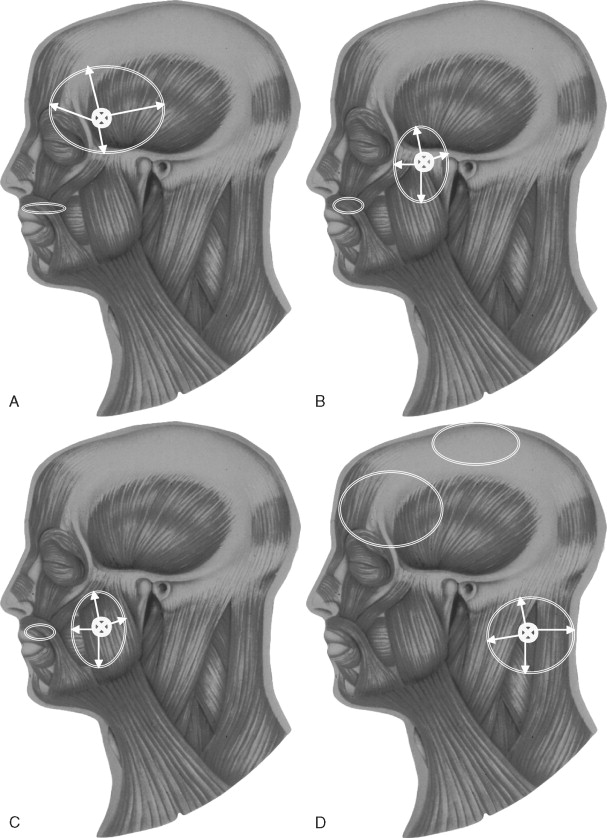

MFP is the most common muscle pain disorder. It is an acute to chronic condition that includes the presence of regional pain associated with tender areas called trigger points (TrPs), which are expressed in taut bands of skeletal muscles, tendons, or ligaments. Although the pain most often occurs in the region over the TrP, pain can be referred to areas distant from the TrP (e.g., the temporalis referring to the frontal area and the masseter referring into the ear and/or the posterior teeth). Reproducible duplication of pain complaints with specific palpation of the tender area is often diagnostic.

Myositis is an acute condition with localized or generalized inflammation of the muscle and connective tissue and is associated pain and swelling overlying the muscle. Most areas in the muscle are tender, with pain in active range of motion. The inflammation is usually due to local causes such as overuse, excessive stretch, drugs (e.g., ecstasy), local infection from pericoronitis, trauma, or cellulitis. Myositis is also termed delayed onset muscle soreness in cases of acute overuse.

Muscle spasm is also an acute disorder characterized by a brief involuntary tonic contraction of a muscle. It can occur as a result of overstretching of a previously weakened muscle, from protective splinting of an injury, as a centrally mediated phenomenon such as prochlorperazine (Compazine)-induced spasm of the lateral pterygoid muscle, or through overuse of the muscle. A muscle in spasm is acutely shortened and painful, with joint range of motion limited. Lateral pterygoid spasm on one side can also cause a shift of the occlusion to the contralateral side.

Muscle contracture is a chronic condition characterized by continuous gross shortening of the muscle with significant limited range of motion. It can begin as a result of factors such as trauma, infection, or prolonged hypomobility. If the muscle is maintained in a shortened state, muscular fibrosis and contracture may develop over several months. Pain is often minimal in the process from protection of the muscle.

ETIOLOGY AND EPIDEMIOLOGY

PREVALENCE

Muscle pain disorders are the most common cause of persistent pain in the head and neck, affecting about 50% of a chronic head and neck pain population. They are also a common cause of pain in the general population, with 20-50% of people having muscle pain disorders and about 6% having symptoms severe enough to warrant treatment.

ETIOLOGIC FACTORS

Onset factors for myogenous TMDs include both direct or indirect macrotrauma to the muscle and repetitive strain activities. Macrotrauma includes a direct blow to the jaw and opening the mouth too wide or for too long a period during activities such as undergoing dental work, eating, yawning, and engaging in sexual activity. Indirect trauma due to a whiplash-type injury may initiate muscle pain in some cases. Local infection and trauma may cause myositis and lead to muscle contracture if not resolved. Occupational and repetitive strain injury may result in MFP and, if acute, muscle spasm. Sleep disturbance and nocturnal habits can contribute to MFP. Psychosocial stressors such as relationship conflicts, monetary problems, feelings of hurriedness, overscheduling, and poor pacing skills can also play an indirect role.

Postural strain caused by a forward head posture, increased cervical or lumbar lordosis, some occlusal abnormalities, and poor positioning of the head or tongue have also been implicated in MFP; so have static postural problems such as unilateral short leg, small hemipelvis, occlusal discrepancies, and scoliosis or functional postural habits such as forward head, jaw thrust, shoulder phone bracing, and lumbar lifting. In a study of postural problems in 164 head and neck muscle pain patients, poor sitting and standing posture in 96%, forward head in 84.7%, rounded shoulders in 82.3%, lower tongue position in 67.7%, abnormal lordosis in 46.3%, scoliosis in 15.9%, and leg length discrepancy in 14.0% were found to contribute to muscle pain.

Oral parafunctional muscle tension produces habits such as teeth clenching, jaw thrust, gum chewing, and jaw tensing. Nocturnal bruxism is often cited as a common cause of MFP but probably is better thought of as a perpetuating cofactor.

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY AND MECHANISMS

Because there are no specific anatomic changes in the myogenous pain, there are no conclusive mechanisms identified in nontrauma cases. Therefore there are several processes that may explain the development and persistence of masticatory myogenous pain.

REPETITIVE STRAIN HYPOTHESIS

Repetitive strain from oral parafunctional habits contributes to localized progressive increases in oxidative metabolism and depleted energy supply (decrease in the levels of adenosine triphosphate [ATP], adenosine diphosphate [ADP], and phosphoryl creatine and abnormal tissue oxygenation). The result is changes in the muscle nociception, particularly with type I muscle fiber types associated with static muscle tone and posture. Tenderness and pain in the muscle are mediated by type III and IV muscle nociceptors, which may be activated by locally released noxious substances such as potassium, histamine, kinins, or prostaglandins, causing tenderness.

NEUROPHYSIOLOGIC HYPOTHESIS

Tonic muscular hyperactivity may be a normal protective adaptation to pain instead of its cause. Phasic modulation of excitatory and inhibitory interneurons supplied by high-threshold sensory afferents may be involved.

CENTRAL HYPOTHESIS

Convergence of multiple afferent inputs from the muscle and other visceral and somatic structures in the lamina I or V of the dorsal horn on the way to the cortex can result in perception of local and referred pain.

CENTRAL BIASING MECHANISM

Multiple peripheral and central factors may inhibit or facilitate central input through modulatory influence of the brainstem. This may explain the diverse factors that can either exacerbate or alleviate the pain, such as stress, repetitive strain, poor posture, relaxation, medications, temperature change, massage, local anesthetic injections, and electrical stimulation.

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY AND MECHANISMS

Because there are no specific anatomic changes in the myogenous pain, there are no conclusive mechanisms identified in nontrauma cases. Therefore there are several processes that may explain the development and persistence of masticatory myogenous pain.

REPETITIVE STRAIN HYPOTHESIS

Repetitive strain from oral parafunctional habits contributes to localized progressive increases in oxidative metabolism and depleted energy supply (decrease in the levels of adenosine triphosphate [ATP], adenosine diphosphate [ADP], and phosphoryl creatine and abnormal tissue oxygenation). The result is changes in the muscle nociception, particularly with type I muscle fiber types associated with static muscle tone and posture. Tenderness and pain in the muscle are mediated by type III and IV muscle nociceptors, which may be activated by locally released noxious substances such as potassium, histamine, kinins, or prostaglandins, causing tenderness.

NEUROPHYSIOLOGIC HYPOTHESIS

Tonic muscular hyperactivity may be a normal protective adaptation to pain instead of its cause. Phasic modulation of excitatory and inhibitory interneurons supplied by high-threshold sensory afferents may be involved.

CENTRAL HYPOTHESIS

Convergence of multiple afferent inputs from the muscle and other visceral and somatic structures in the lamina I or V of the dorsal horn on the way to the cortex can result in perception of local and referred pain.

CENTRAL BIASING MECHANISM

Multiple peripheral and central factors may inhibit or facilitate central input through modulatory influence of the brainstem. This may explain the diverse factors that can either exacerbate or alleviate the pain, such as stress, repetitive strain, poor posture, relaxation, medications, temperature change, massage, local anesthetic injections, and electrical stimulation.

CLINICAL PRESENTATION

The major characteristics of masticatory myalgia include pain, muscle tenderness, limited range of motion, and other symptoms such as fatigability, stiffness, and subjective weakness. Comorbid conditions and complicating factors are also common and discussed. Each will be discussed for the different subtypes.

PAIN

The common sites of pain in the masticatory system include jaw pain; facial pain; temple, frontal, or occipital headaches; preauricular pain; earache; and neck pain. The pain is often a constant steady dull ache that fluctuates in intensity and can be acute to chronic. The duration may vary from hours to days.

MUSCLE TENDERNESS

In MFP the tenderness is in a deep, localized (2 to 5 mm), taut band of skeletal muscle, a TrP, which is associated with consistent patterns of pain referral. In contrast, muscle tenderness in myositis and muscle spasm can be generalized over the whole muscle. Myofascial TrPs are very common and may be active or latent. Active TrPs are hypersensitive and display continuous pain in the zone of reference that can be altered with specific palpation. Latent TrPs display only hypersensitivity with no continuous pain. This localized tenderness has been found to be a reliable indicator of the presence and severity of MFP with both manual palpation and pressure algometers. However, the presence of taut bands appears to be a characteristic of skeletal muscles in all subjects regardless of the presence of MFP. Palpating the active TrP with sustained deep single finger pressure on the taut band will elicit an alteration of the pain (intensification or reduction) in the zone of reference (area of pain complaint) or cause radiation of the pain toward the zone of reference. This can occur immediately or be delayed a few seconds. The pattern of referral is both reproducible and consistent with patterns of other patients with similar TrPs ( Figure 53-1 ). This enables a clinician to use the zone of reference as a guide to locate the TrP for purposes of treatment.

LIMITED RANGE OF MOTION

Diminished mandibular opening may result from structural disorders of the TMJ system such as ankylosis, internal derangements, coronoid hypertrophy, or gross osteoarthritis, all of which must be ruled out by clinical examination and joint imaging. In MFP, limitation in range of motion may be slight (10-20%) and unrelated to joint restriction, whereas in muscle spasm, myositis, and contracture it may be gross (50% or more). A study of jaw range of motion in patients with MFP and no joint abnormalities demonstrated a slightly diminished range of motion of 35 to 45 mm (approximately 10% compared with unaffected individuals) and pain in the full range of motion. This is considerably less limitation than was found with joint locking due to a TMJ internal derangement (20 to 35 mm). This restriction may perpetuate the TrP and develop other TrPs in the same muscle and in other agonist muscles. This can cause multiple TrPs with overlapping areas of pain referral, with subsequent changes in pain patterns over time as TrPs are inactivated.

OTHER SYMPTOMS

Other associated signs and symptoms that may occur include increased fatigability, stiffness, subjective weakness, pain in movement, otologic symptoms including dizziness, tinnitus, and plugged ears, paresthesias including numb feelings, decreased sensation and tingling, and dermatographia including increased redness of the skin on palpation or rolling. The affected muscles may also display an increased fatigability, stiffness, subjective weakness, pain in movement, and slight restricted range of motion that is unrelated to joint restriction. The muscles are painful when stretched, causing the patient to protect the muscle through poor posture and sustained contraction. There are no neurologic deficits associated with muscle pain disorders unless a nerve entrapment syndrome with weakness and diminished sensation coincides with the muscle tightness. Although routine clinical electromyography (EMG) shows no significant abnormalities associated with TrPs, some specialized EMG studies reveal differences. The consistency of soft tissues over the TrPs has been found to be denser than over adjacent muscle. Skin overlying the TrPs in the masseter muscle appears to be warmer as measured by infrared emission.

COMORBID CONDITIONS AND COMPLICATING FACTORS

There are many comorbid conditions with myogenous TMD pain that reflect both common causative factors and mechanisms of pain. In most recent classifications, the regional pain found with MFP is distinguished from the widespread muscular pain associated with fibromyalgia (FM). These two disorders have many similar characteristics and may represent two ends of a continuous spectrum. For example, as Simons points out, 16 of the 18 tender point sites in FM lie at well-known TrP sites. Many of the clinical characteristics of FM such as fatigue, morning stiffness, and sleep disorders can also accompany MFP. Bennett compares these two disorders and concludes that they are two distinct disorders but may have similar underlying pathophysiology. The clinical significance of distinguishing between them lies in the more common centrally generated contributing factors in FM (sleep disorders, depression, and stress) versus the more common regional contributing factors in MFP (trauma, posture, and muscle tension habits) as well as the better prognosis in treatment of MFP as compared with FM.

Other comorbid conditions that have often been cited to accompany myogenous disorders include joint disk displacement and osteoarthritis, malocclusion and functional occlusal dysfunction, connective tissue diseases, neuropathic pain disorders, migraine and tension type headaches, gastrointestinal disorders, and hypothyroidism. It is not clear what mechanism underlies the coexistence of these conditions. Common central and peripheral pain mechanisms and causes may play a role.

Furthermore, many associated behavioral and psychosocial factors can accompany the chronic pain associated with myogenous disorders including behavioral factors such as muscle tension, oral parafunctional, and maladaptive postural habits; psychologic factors such as frustration, anxiety, and depression; secondary gain from pain behaviors such as pain verbalization and avoidance of activities; medication dependencies; and sleep disturbance.

DIAGNOSTIC TESTS

Diagnoses of masticatory myalgia are typically determined through the clinical diagnostic criteria that are listed in Box 53-1 . However, some diagnostic strategies can be helpful. In MFP, injections of local anesthetic into the active TrP will reduce or eliminate the referred pain and the tenderness. Imaging studies often used to evaluate for dental or TMJ disease, including radiographs and magnetic resonance imaging, are generally normal. Routine clinical EMG studies are abnormal in muscle spasm only. Some specialized EMG studies (twitch response) reveal differences in cases of MFP but have limited applicability in routine clinical practice. Blood and urine studies are generally normal unless caused by a concomitant disorder. Pain questionnaires such as the Chronic Pain Battery and TMJ Scale may identify contributing factors including emotional issues, somatization, secondary gain, and disability.

Myofascial Pain—Repetitive Strain

- •

Dull aching pain in the jaw, face, ear, temples, or forehead

- •

Localized tenderness (trigger points) in specific taut muscle bands with tenderness on the same side as the pain; see Figure 53-1 for sites and referral patterns

- •

Duplication of the pain with palpation of the tender trigger points

Muscle Spasm—Acute Overuse

- •

Acute onset of pain in the jaw, face, ear, or temples at rest and in function

- •

Moderate to severe acute limited range of motion due to continuous muscle contraction; in lateral pterygoid spasm, the jaw has a shift to one side with subsequent acute malocclusion that is reversible

- •

Generalized tenderness of the muscle

Myositis—Injury or Infection

- •

Pain, usually continuous, in a localized muscle area after injury or infection; pain is increased with mandibular movement

- •

Diffuse tenderness over the entire muscle area involved

- •

Moderate to severe limited range of motion

- •

Swelling over muscle area involved

Muscle Contracture—Muscle Fibrosis

- •

Gross limited range of mandibular motion

- •

Unyielding firmness on passive stretch (hard end feel)

- •

Little or no pain unless the involved muscle is forced to lengthen

- •

Remote history of trauma, infection, or long period of disuse and limited range of motion

TREATMENT

SIMPLE TO COMPLEX

Treatment of myogenous pain can range from simple cases with transient single muscle syndromes to complex cases involving multiple muscles and many interrelating contributing factors. Many authors have found success in treatment of myogenous pain using a wide variety of techniques such as exercise, TrP injections, vapocoolant spray and stretch, transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS), biofeedback, posture correction, tricyclic antidepressants, muscle relaxants and other medications, and addressing of perpetuating factors. However, the difficulty in management lies in the critical need to match the level of complexity of the management program with the complexity of the patient. Failure to address the entire problem including all involved muscles, concomitant diagnoses, and contributing factors may lead to failure to resolve the pain or, worse, perpetuation of the pain.

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses