Basal cell carcinoma, p. 154).

• Photodynamic therapy (PDT).

Lentigo maligna (Hutchinson’s melanotic freckle)

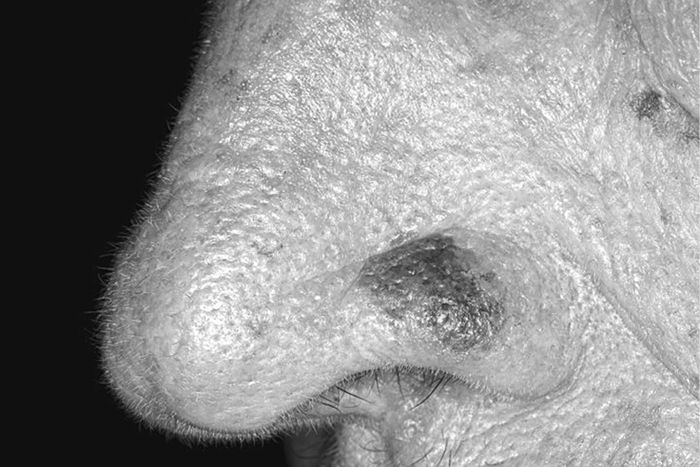

• Common, pigmented, often large macule on head and neck (see Fig. 3.1).

• Histologically a proliferation of atypical melanocytes—a melanoma in situ.

• Risk of progression unknown.

• Biopsy may be indicated (of darker or changing areas).

• Treatment: none in very elderly?

• Surgical excision is treatment of choice.

• RT/cryotherapy/imiquimod—in larger lesions.

• No need to follow-up surgically excised cases. Others should be reviewed for 3–5 years.

Melanocytic intra-epidermal neoplasia (MIN)

• UK-based histopathological term, not adopted worldwide.

• Melanocytic proliferation confined to epidermis.

• Essentially melanoma in situ.

Fig. 3.1 Lentigo maligna.

Skin cancer

Common types

• Basal cell carcinoma (rodent ulcer) (BCC).

• Cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma (cSCC).

• Cutaneous malignant melanoma (cMM).

All types are increasing and related to sunlight exposure.

There are 135,000 cases in England and Wales per annum, but registration of BCC and cSCC (non-melanoma skin cancer (NMSC)) varies widely and thus is under-reported.

Rarer skin tumours include:

• Merkel cell carcinoma.

• Cutaneous T-cell lymphoma.

• Secondary deposits, e.g. lung, breast.

In the UK, NICE published guidance in 2006, ‘Improving outcomes for people with skin tumours including melanoma’, which outlined how healthcare services for skin cancer patients should be organized, with emphasis on MDTs caring for patients with high-risk tumours. NICE is currently preparing new guidelines specific to melanoma, due to be published in 2015.

Basal cell carcinoma

Background

• Commonest human cancer.

• >80% of skin tumours, and >80% on the head and neck.

• Slowly growing, locally invasive, and destructive, often pearly with telangiectasia.

Risk factors

• Chronic UV radiation.

• Genetic predisposition/fair skin type.

• Male sex.

• Immunosuppression—post transplant, haematological malignancy, anti-tumour necrosis factor (TNF) drugs (e.g. infliximab).

• Exposure to arsenic (rare).

• Gorlin–Goltz syndrome (see ![]() Gorlin–Golz syndrome, p. 401).

Gorlin–Golz syndrome, p. 401).

• Xeroderma pigmentosum.

Diagnosis

• Usually clinical.

• Incisional/punch biopsy may be of value in cases of doubt.

• Extensive lesions: CT or MRI to determine bone or major structure involvement.

Morphological types

• Cystic.

• Nodular.

• Morphoeic (sclerosing).

• Superficial.

• Combinations of the types, e.g. nodulocystic (Fig. 3.2).

These can all have keratotic, ulcerated, and pigmented variants.

Fig. 3.2 Nodulocystic BCC.

Histological subtypes: less aggressive

• Nodular.

• Superficial (multicentric).

Histological subtypes: more aggressive

• Morphoeic.

• Infiltrative.

• Micronodular.

• Basosquamous.

These types may show the most aggressive features of perineural and perivascular invasion.

High-risk factors for BCCs

• Site: midface.

• Size: >2cm.

• Histology: aggressive features.

• Recurrent tumour.

Treatment options

• None: e.g. in the elderly or the medically compromised.

• Surgical: excision or destruction.

• Non-surgical.

Surgical treatment of BCC

Excision with predetermined margins

Recommended treatment by British Association of Dermatologists (BAD):

• In nodular BCC:

• 3mm margin will give tumour clearance in 85% of cases;

• 4–5mm margin gives clearance in 95% of cases.

• In primary morphoeic BCC:

• 3mm margin gives clearance in 66%;

• 5mm—82%;

• 13mm—95%.

• Incomplete excision rates of BCC reported as 4–7%, and as high as 40% at medial canthus.

Re-excision

Recommended in:

• Midface/critical site.

• Aggressive histology.

• Deep margin involvement.

• Recurrent tumour.

Mohs micrographic surgery

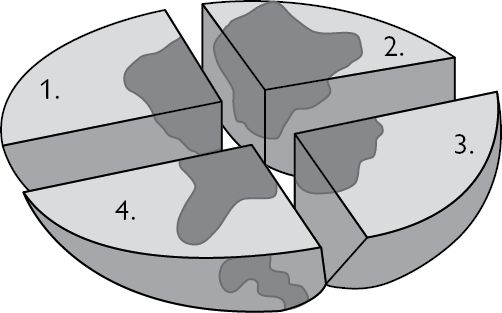

• Aims to identify and remove all tumour by histologically guided re-excision before reconstruction (Fig. 3.3).

• Labour intensive.

• High rates of cure reported.

• Consider in:

• recurrent disease;

• other high-risk tumours;

• where minimal tissue loss desired, e.g. anatomically sensitive areas such as peri-orbital tissues.

• Also has role to play in the management of some other malignant skin tumours, e.g. cSCC.

• Variations include:

• excision and intra-operative frozen section;

• excise, wait for haematoxylin and eosin (H&E) result, and delayed reconstruction (slow Mohs).

Fig. 3.3 Mohs surgery.

Destructive surgical techniques

Not recommended in high-risk tumours:

• Curettage and cautery: common Tx by dermatologists.

• Cryosurgery.

• Laser.

• Higher recurrence rates than with surgical excision.

Non-surgical treatment of basal cell carcinoma

Not recommended in forms of BCC other than superficial:

Imiquimod

• An immune modulator that stimulates T cells (used in treatment of genital warts).

• 80% cure rate in primary small superficial BCC, used 5 times per week for 6 weeks.

PDT

• Topical methyl aminolevulinate (MAL) greater clearance than aminolevulinic acid (ALA).

• Similar cure rate to imiquimod in superficial BCC.

Radiotherapy

• Treatment of choice where the patient is unwilling or unable to tolerate surgery and treatment is desirable.

• Usually superficial electrons.

• Can be:

• single fraction (higher complications);

• fractionated (commonly 5 doses)—higher cure rate with lower complications.

• Complications:

• soft tissue radionecrosis; including underlying cartilage;

• cataracts;

• up to 5% telangiectasia;

• secondary RT-induced cancers.

• Higher recurrence than with surgical excision (up to 10% vs 2%).

Advanced/metastatic BCC

• Metastatic BCC vanishingly rare.

• No standard therapy for this group; clinical trials appropriate if available.

• BCCs often exhibit activation of the Hedgehog/PTCH1-signalling pathway.

• Use of oral/topical hedgehog pathway inhibitors currently under investigation in patients with advanced, multiple or metastatic BCC, e.g. vismodegib.

Follow-up of BCC

• Risk of a second BCC is 33–77%.

• Those with completely excised first BCC can be discharged with information.

• Those with more than two BCCs have 70% chance of a further BCC. Consider surveillance by GP or dermatologist.

Cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma

Background

• >10% of skin cancers (second commonest).

• 80% involve the head and neck.

• Locally invasive.

• 5% of all cSCC metastasize.

• Up to 30% high risk, head and neck cSCCs metastasize.

Risk factors

• Chronic UV radiation.

• Genetic predisposition/fair skin type.

• Male sex.

• Immunosuppression (as per BCC).

• Xeroderma pigmentosum, albinism.

• Exposure to arsenic (rare).

• May arise in chronic wounds, scars, burns, sinus tracts.

• Can follow Bowen’s disease, actinic keratosis.

Presentation

• Ulcer, nodule, or keratin horn; often rapidly growing.

• Diagnosis: clinical/histological.

High-risk SCC

For recurrence or metastasis:

• Site: lip, ear, non-sun exposed sites, those arising in chronic wounds, after RT, and from Bowen’s disease.

• Size >2cm.

• Depth >4mm.

• Histology: poorly differentiated, perineural infiltration.

• Immunosuppression.

Staging of cSCC

• Continues to evolve.

• American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) 2010 guidance: ‘Cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma and other cutaneous carcinomas’ (see ![]() Further reading, p. 174).

Further reading, p. 174).

• Aiming to achieve parity with mucosal SCC TNM staging system.

• Incorporates primary tumour risk factors into T stage.

• Two or more high-risk factors increases primary tumour from T1 to T2.

• Nodal staging now takes into account number and size of nodal disease.

•

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses