Chapter 9

Study Appraisal: Cohort Studies

Aim

This aim of this chapter is to outline how to appraise a cohort study, explain what risk and odds ratios are and show how to calculate them.

Outcomes

On completion of this chapter the reader should understand the key differences between RCT and cohort studies and have a list of questions to be able to appraise a cohort study.

What Is a Cohort Study?

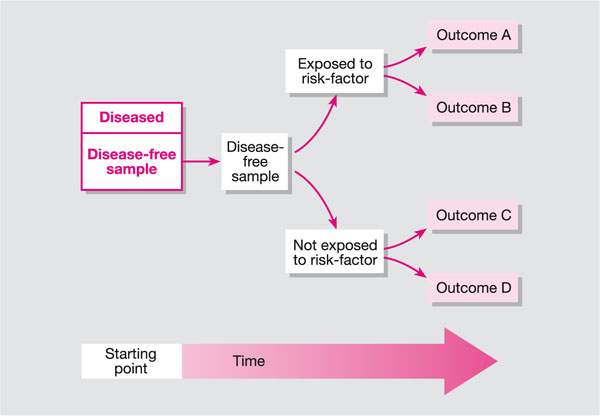

A cohort study is an observational study; it differs from a clinical trial in that the researchers are not directly trying to treat or prevent a disease or condition. A cohort study is one in which a group of participants is studied over time (Fig 9-1). The group can be selected to represent a population of interest (e.g. smokers, patients with oral lichen planus or leukoplakia), or they could be a group of individuals linked in some way, for example a birth cohort (all those born during a particular period), a disease, education or employment. Participants are followed over time and data are collected on health outcomes and/or exposure to risk factors. A cohort study can be either prospective or retrospective.

Fig 9-1 Cohort study.

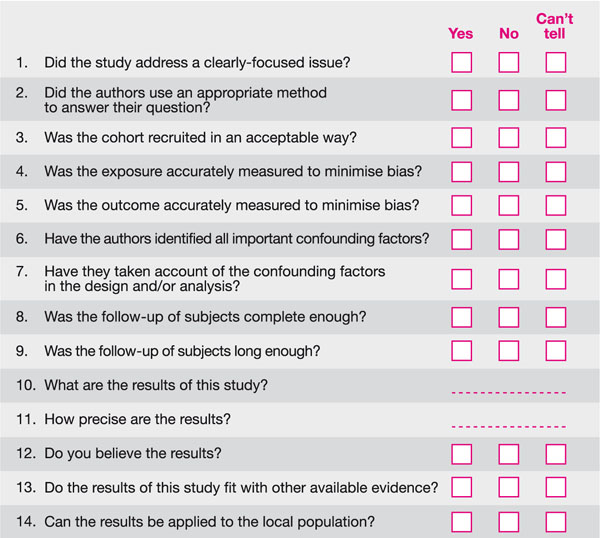

Randomised controlled trials are considered the best method for providing evidence on efficacy. However, they are criticised for focusing on highly selected patients and outcomes, and are subject to ethical and logistical constraints (Black, 1996). Cohort studies can address some of these issues, evaluating larger groups of diverse individuals over long periods with the possibility of providing information on a range of outcomes and possibly rare events. While cohort studies have potential to provide useful evidence, concerns regarding the validity of evidence derived from them have been raised. A comparison with randomised controlled studies is shown in Table 9-1 on page 79. In terms of appraising cohort studies CASP provides a similar tool to that available for randomised controlled trials (Fig 9-2 on page 80).

| Item | Cohort studies | Randomised controlled trials |

| Populations studied | Diverse populations of patients who are observed in a range of settings | Highly selected populations recruited on the basis of detailed criteria and treated at selected sites |

| Allocation to the intervention | Based on decisions made by providers or patients | Based on chance and controlled by investigators |

| Outcomes | Can be defined after the intervention and can include rare or unexpected events | Primary outcomes are determined before patients are entered into study and are focused on predicted benefits and risks |

| Follow-up | Many cohort studies rely on existing experience (retrospective studies) and can provide an opportunity for long follow-up | Prospective studies; often have short follow-up because of costs and pressure to produce timely evidence |

| Analysis | Sophisticated multivariate techniques may be required to deal with confounders | Analysis is straightforward |

Fig 9-2 CASP questions to appraise a cohort study.

The CASP Questions

Did the Study Address a Clearly Focused Issue?

As with randomised controlled trials we are looking for a clear idea of the focus of the study in terms of the population studied, any risk factors studied, the outcomes considered and clarity on whether the study tried to detect a beneficial or harmful effect.

Did the Authors Use an Appropriate Method to Answer their Question?

In other words, was a cohort study a good way of answering the question under the circumstances? Was it the right study design to choose; was a randomised controlled trial an inappropriate, unfeasible or unethical way to address the question?

Was the Cohort Recruited in an Acceptable Way?

The internal validity of a study is defined as the extent to which the observed difference in outcomes between the two comparison groups can be attributed to the intervention rather than to other factors.

So, we are looking to see if the study designers have tried to avoid a selection bias. Selection bias is defined by CONSORT (Altman et al., 2001) as a systematic error in creating intervention groups, causing them to differ with respect to prognosis. The groups differ in measured or unmeasured baseline characteristics because of the way in which participants were selected for the study or assigned to their study groups.

Things you need to consider are:

-

Was the cohort representative of a defined population?

-

Was there something special about the cohort?

-

Was everybody included who should have been included?

Was the Exposure Accurately Measured to Minimise Bias?

Here you are looking to see if there has been any bias in the way in which the exposure being studied has been measured or classified. The more objectively any given exposure can be measured the better. For example, it is well known that asking people whether or not they are still smoking may not elicit an accurate response so this is a subjective method, while measuring salivary cotinine levels is a more objective measure (van Vunakis et al., 1989).

It is also important to understand whether measures truly reflect what you are looking for and have been validated. We also need to know whether all the subjects are classified into exposure groups using the same procedures.

Have the Authors Identified All Important Confounding Factors?

Confounding is a term that describes a situation in which the estimated intervention effect is biased because of some difference between the comparison groups apart from the planned interventions. This could be baseline characteristics (e.g. socio-economic background), factors affecting prognosis (e.g. smoking status), or concurrent treatments. Age and sex are the most common confounding variables in health-related studies because these two variables are not only associated with most exposures we are interested in such as diet, smoking habits, physical exercise etc., but they are also independent risk factors for most diseases.

Which ones do you think are important and have the authors missed any important ones?

Have they Taken Account of the Confounding Factors in the Design and/or Analysis?

In a cohort study, confounding can be dealt with at the design stage of a study by:

-

Matching. This is normally only done for well-known confounders and selects comparison groups with similar backgrounds (e.g. non-smokers are matched with other non-smokers, while smokers are matched with other smokers).

-

Restriction. This limits participation in a study to specific groups that are similar to each other with respect to the confounder (e.g. if smoking is likely to be a confounder then only non-smokers will be included in the study).

Confounding can also be controlled for in the analysis by:

-

Stratification. Here the strength of the association is measured separately in each well-defined sub-group (e.g. regular attenders and those who attend with a problem). Using statistical techniques, overall summary measures of the association can be obtained and adjusted or controlled for the effects of the confounder.

-

Statistical modelling. There are more advanced techniques that simultaneously take into consideration the effects of all the possible confounders that have been recorded by the investigators.

Was the Follow-up of Subjects Complete Enough?

And Was the Follow-up of Subjects Long Enough?

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses