This case report presents the camouflage treatment that successfully improved the facial profile of a patient with a skeletal Class III malocclusion using bone-borne rapid maxillary expansion and mandibular anterior subapical osteotomy. The patient was an 18-year-old woman with chief complaints of crooked teeth and a protruded jaw. Camouflage treatment was chosen because she rejected orthognathic surgery under general anesthesia. A hybrid type of bone-borne rapid maxillary expander with palatal mini-implants was used to correct the transverse discrepancy, and a mandibular anterior subapical osteotomy was conducted to achieve proper overjet with normal incisal inclination and to improve her lip and chin profile. As a result, a Class I occlusion with a favorable inclination of the anterior teeth and a good esthetic profile was achieved with no adverse effects. Therefore, the hybrid type of bone-borne rapid maxillary expander and a mandibular anterior subapical osteotomy can be considered effective camouflage treatment of a skeletal Class III malocclusion, providing improved inclination of the dentition and lip profile.

Highlights

- •

Alternative camouflage treatment for skeletal Class III malocclusion is presented.

- •

Bone-borne maxillary expander provides effective skeletal effects in a young adult.

- •

Two surface-treated mini-implants and premolars to be extracted support expansion.

- •

Mandibular anterior subapical osteotomy is performed under local anesthesia.

- •

Mandibular anterior subapical osteotomy improves incisor inclination and lip profile.

Mandibular prognathism can be treated with mandibular setback surgery to achieve an ideal facial profile and occlusion. If the skeletal disharmony is moderate, the clinician can consider orthodontic camouflage treatment. This typically involves further lingual tipping of the mandibular incisors that are already excessively lingually tipped, without fully improving the facial profile. Moreover, periodontal integrity can be degraded with camouflage orthodontic treatment when the mandibular incisors’ roots are forced against the thin alveolar bone housing. It is possible to design a camouflage treatment that will improve the facial profile and achieve a normal inclination of the mandibular incisors.

Mandibular prognathism is often accompanied by a transverse discrepancy, characterized by a narrow maxillary basal arch, a deficient perimeter, and associated crowding of the maxillary dentition. In camouflage treatment, nonsurgical maxillary expansion can be planned using tooth-anchored maxillary expanders. This protocol has some disadvantages. Skeletal expansion lags behind dental expansion. The teeth are severely tipped to the buccal aspect, and a bone dehiscence is likely. To prevent these adverse effects, rapid maxillary expansion supported by skeletal anchorage has been used.

In this report, we present a patient with mandibular prognathism and a transverse deficiency. The patient was successfully treated with a hybrid type of bone-borne rapid maxillary expander (RME) and a mandibular anterior subapical osteotomy (ASO). The purpose of this report is to suggest that the hybrid type of bone-borne RME and a mandibular ASO are an effective camouflage treatment option for mandibular prognathism.

Diagnosis and etiology

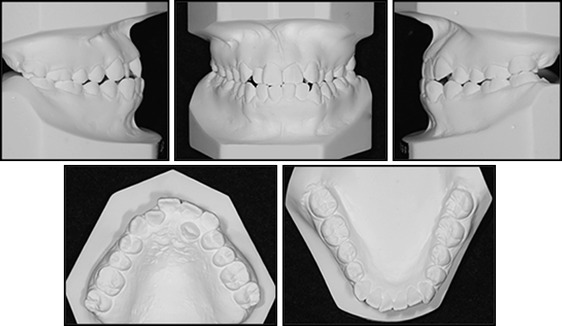

An 18-year-old woman complained of crooked teeth and mandibular prognathism. The clinical examination showed that she had mandibular prognathism, a relatively long lower face, and moderate facial asymmetry with the chin deviating to the left ( Fig 1 ). Her protruded lip profile was affected by a flat mentolabial sulcus, lip incompetency with a short philtrum, and mentalis hyperactivity. The display of the maxillary incisors was within the normal range. The intraoral examination showed Class III molar and canine relationships on the right and Class I molar and Class II canine relationships on the left with an anterior crossbite ( Figs 1 and 2 ). A deficient posterior buccal overjet with a crossbite in the left premolar area and lingually tipped mandibular posterior teeth described the transverse discrepancy. The arch length discrepancies were −12.9 mm in the maxilla and −2.8 mm in the mandible. The maxillary left lateral incisor was totally blocked out to the palatal side. There was no history of temporomandibular joint dysfunction.

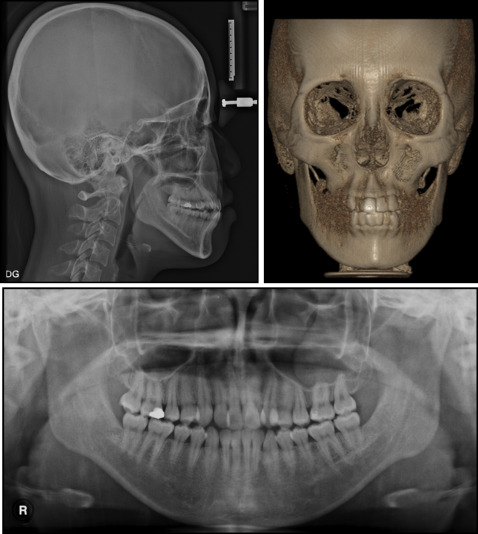

The initial lateral cephalometric analysis showed a skeletal Class III relationship (ANB, −0.4°) with normal mandibular length (effective mandibular length, 123 mm; ratio of mandibular body to anterior cranial base, 1.1) and a hyperdivergent pattern (FMA, 31.7°) ( Fig 3 ; Table I ). The inclinations of the maxillary and mandibular incisors were within the normal ranges (U1 to FH, 117°; IMPA, 86.1°). The frontal image of reconstructed computed tomograms showed a 1-mm deviation of the mandible to the left ( Fig 3 ). The maxillary dental midline was deviated by 1.5 mm to the left, whereas the mandibular dental midline was coincident with the facial midline ( Figs 1 and 3 ). There were no pathologic findings from the panoramic radiograph. The patient was diagnosed with a skeletal Class III malocclusion with transverse discrepancy.

| Variable | Mean | SD | Pretreatment | Posttreatment | Difference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sagittal | |||||

| ANB (°) | 3.45 | 1.87 | −0.4 | 3.0 | 3.4 |

| SNA (°) | 81.08 | 3.73 | 79.8 | 79.0 | −0.8 |

| SNB (°) | 78.01 | 3.81 | 80.2 | 76.2 | −4 |

| A-point to N-perp (mm) | 0.4 | 2.3 | −1.2 | −2.2 | −1 |

| Pog to N-perp (mm) | −1.8 | 4.5 | −1.0 | −4.5 | −3.5 |

| Wits appraisal (mm) | −2.74 | 0.3 | −5.0 | −3.5 | 1.5 |

| Effective mandibular length (mm) | 121.6 | 4.5 | 123.0 | 123.0 | 0 |

| Mandibular body to anterior cranial base (ratio) | 1.08 | 0.03 | 1.1 | 1.1 | 0 |

| Vertical | |||||

| Sum (°) | 397.16 | 6.63 | 401.6 | 405.1 | 3.5 |

| Saddle angle (°) | 125.45 | 5.32 | 118.8 | 118.8 | 0 |

| Articular angle (°) | 147.68 | 5.25 | 151.0 | 154.5 | 3.5 |

| Gonial angle (°) | 124.31 | 5.36 | 131.8 | 131.8 | 0 |

| SN-FH (°) | 10.0 | 10.0 | 0 | ||

| FH to palatal plane angle (°) | 1.2 | 4.72 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0 |

| FH to occlusal plane angle (°) | 29.63 | 5.66 | 5.5 | 12.3 | 6.8 |

| FH to mandibular plane angle (°) | 29.63 | 5.66 | 31.7 | 34.8 | 3.1 |

| Facial height ratio (posterior/anterior) | 65.3 | 8.75 | 0.63 | 0.61 | −0.02 |

| ANS-Me/N-Me (ratio) | 0.55 | 0.02 | 0.74 | 0.74 | 0 |

| Dental | |||||

| U1-FH (°) | 113.8 | 6.37 | 117.0 | 112.2 | −4.8 |

| U1 to SN (°) | 105.28 | 6.64 | 107.0 | 101.0 | −6 |

| IMPA (°) | 91.62 | 5.23 | 86.1 | 87.5 | 1.4 |

| Overbite (mm) | 2.5 | 1 | 0.0 | 1.0 | 1 |

| Overjet (mm) | 2.5 | 1 | 0.5 | 2.5 | 2 |

| Soft tissue | |||||

| Upper lip to E-line (mm) | 0.86 | 2.36 | −2.5 | −1.5 | 1 |

| Lower lip to E-line (mm) | 5.87 | 2.93 | 3.7 | 0.7 | −3 |

| Superior labial sulcus angle (°) | 119 | 7.3 | 82.0 | 86.5 | 4.5 |

| Inferior labial sulcus angle (°) | 122 | 11.7 | 141.0 | 122.5 | −18.5 |

Treatment objectives

The treatment objectives were to (1) establish an esthetic facial profile, (2) resolve the transverse skeletal and dental discrepancies, (3) establish proper occlusion with normal inclinations of the teeth, (4) correct the midline discrepancy, (5) maintain good periodontal health, and (6) accept a mild mandibular asymmetry.

Treatment objectives

The treatment objectives were to (1) establish an esthetic facial profile, (2) resolve the transverse skeletal and dental discrepancies, (3) establish proper occlusion with normal inclinations of the teeth, (4) correct the midline discrepancy, (5) maintain good periodontal health, and (6) accept a mild mandibular asymmetry.

Treatment alternatives

This skeletal discrepancy would typically lead to a treatment plan including orthognathic surgery. In this approach, vertical facial height could also be improved with impaction of the maxilla, a mandibular setback, and a reduction genioplasty. Extraction of the maxillary first premolars would be part of the plan because of the arch length discrepancy and the interarch width relationship.

Another option was camouflage treatment, accomplished via extraction of the maxillary and mandibular premolars. Expansion of the maxilla would also be necessary to correct the transverse discrepancy and increase the arch perimeter. The mandibular ASO would allow the clinician to retract the mandibular incisors without increasing their lingual inclinations. The anterior alveolar bone housing and teeth within would be moved as a block. A mandibular ASO has the additional advantage of early improvement of the lip profile.

A bone-borne type of maxillary expander was preferred because it minimizes buccal flaring of the posterior teeth and associated periodontal complications. The C-expander, a bone-borne RME appliance, was reported previously. The expander device is supported by 4 mini-implants: 2 between the canines and first premolars, and the other 2 between the second premolars and first molars. In this patient, there was a lack of space for the mini-implant because of the severe crowding in the left canine and premolar area. Consequently, these teeth were used as part of the anchor system until the extractions were performed.

The patient and her family chose camouflage orthodontic treatment because they did not want orthognathic surgery under general anesthesia. In the Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery at Kyung Hee University dental hospital in Seoul, Korea, we typically perform the mandibular ASO under local anesthesia. The patient was informed about postsurgical complications.

Treatment progress

The treatment was started with placement of the hybrid type of bone-borne RME (C-expander) and simultaneous mandibular ASO. The hybrid type of C-expander (bone and tooth borne) consists of 4 parts: palatal mini-implants, premolar bands, an expansion screw, and an acrylic body. Between the second premolar and the first molar on each side, 2 sandblasted with large grit and acid-etched C-implants (1.8-mm diameter, 8.5-mm length; CIMPLANT Company, Seoul, Korea) were placed on the palatal slope 8 mm apical from the alveolar ridge. Bands were adapted to the first premolars, and a pickup impression was taken to fabricate a hybrid type of C-expander. The bands were soldered to the wire of the expansion screw, and an acrylic resin body was fabricated on the cast model along the surface of the hard palate. The bands of the fabricated body were cemented to the first premolars, and the body was connected to the mini-implants by adding acrylic resin ( Fig 4 ).