The increasing acceptance of dental implant therapy has largely been the result of the ability to predictably obtain a rigid bone-implant interface. The overlying soft tissue architecture and consistency are now being scrutinized in an attempt to achieve improved implant longevity and/or aesthetics. This chapter will review the indications for soft tissue procedures around implants and describe techniques to improve these soft tissue parameters.

▪

SOFT TISSUE HEALTH CONSIDERATIONS AROUND IMPLANTS

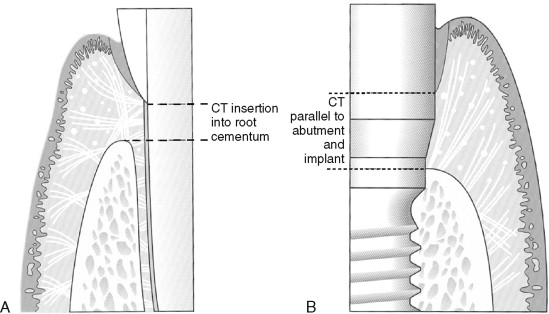

The composition of the epithelial and connective soft tissues surrounding dental implants has been established to be similar to that of natural teeth. A junctional epithelium forms a hemidesmosomal attachment to the implants and natural teeth, approximating 2 mm in length ( Figure 28-1 ). The connective tissue interface, however, is different based on the attachment orientation geometry and type of attachment. The connective tissue zone is approximately 1 mm around teeth and 2 mm around implants. Collectively, the junctional and connective tissue attachment is referred to as the soft tissue “seal.”

Differences in the soft tissue connections involve the fact that connective tissue directly attaches to the acellular root cementum of a tooth, whereas the connective tissue around implants runs parallel to the implant surface and inserts into the bone. In addition, the periimplant connective tissue has significantly higher collagen content and less fibroblasts. The significantly reduced vascularity of the periimplant connective tissue is thought to place this attachment mechanism at higher risk for bacteria-induced inflammatory breakdown. It is therefore preferable to provide dimensions and quality of soft tissue that are more resistant to bacterial-induced bone loss and thus reduce the chance of subsequent implant failure or aesthetically compromising recession.

Historically, adequate dimensions of bound keratinized tissue have been the gold standard for mucogingival health around teeth and implants. Wennstrom challenged this belief, suggesting that a movable mucosa around an implant permucosal extension or abutment can be a stable end point if adequately maintained. Most authors, however, agree that long-term stability is more probable with bound tissue, keratinized or not. Unbound tissue of either keratinized or mucosal origin would be least desirable because of the potential for either increased pocket depth or recession.

▪

SOFT TISSUE AESTHETIC CONSIDERATIONS FOR IMPLANTS

Lack of aesthetics around implants can be a deficiency of several soft tissue factors, including color, contour, and consistency. Specific problems within these categories include loss or reduction of the interdental papilla, increased crown height, and exposure of implant margin. It is the author’s observation that many of these common problems arise during the restorative phase of treatment when surgical solutions are not possible, feasible, or well accepted by the patient. It therefore behooves the surgeon to understand and communicate to the patient any potential or preexisting aesthetic compromises that are present or may occur as a result of anatomic considerations. The patient’s expectations should be elucidated, recorded, and harmonious with those of the treating clinician.

Methods of communicating expectations of this sort use a nomenclature system, such as established by Palacci and Ericsson or Misch. The Palacci and Ericsson defect classification scheme is based on four classifications of vertical dimension and four classifications of horizontal dimension. The three-category classification system of Misch is of particular utility when discussing the anticipated appearance of the final restoration with patients. The system for fixed implant restorations classification divides the desired prosthesis into one of three categories: FP-1, FP-2, and FP-3. These options depend on the amount of hard and soft tissue replaced and serve to convey the appearance of the final prosthesis to all implant team members ( Table 28-1 ). Ridge deficiencies described by these systems are most frequently the result of a hard tissue deficiency, which should be addressed early in the treatment plan.

| Type | Definition |

|---|---|

| FP-1 | Fixed prosthesis; replaces only the crown; looks like a natural tooth. |

| FP-2 | Fixed prosthesis; replaces only the crown and a portion of the root; crown contour appears normal in the occlusal half, but is elongated or hypercontoured in the gingival half. |

| FP-3 | Fixed prosthesis; replaces missing crowns and gingival color and portion of the edentulous site; prosthesis most often uses denture teeth and acrylic gingival, but may be porcelain to metal. |

| RP-4 | Removable prosthesis; overdenture supported completely by implant. |

| RP-5 | Removable prosthesis; overdenture supported by both soft tissue and implant. |

Advanced diagnostic techniques, such as CT imaging, are useful to assess and quantify the need for hard and soft tissue support. Preliminary replacement of deficient hard tissues should be addressed before considering soft tissue augmentation. A ridge deficiency at the implant site should be corrected to within 3 mm of its optimal contour. Techniques for diagnosing and treating hard tissue defects are addressed in another chapter.

The likelihood of developing aesthetic complications is additionally based on tissue biotype. Tissue types have been categorized into two forms: thin and scalloped, or thick and flat. The stability of the osseous crest and position of the free-gingival margin are directly proportional to the thickness of the bone and gingival tissue. Kan et al. found that with implants, the level of the interproximal papilla of the implant is independent of the proximal bone level next to the implant, but is related to the interproximal bone level next to the adjacent teeth. He also found that even with ideal execution, facial and/or interproximal gingival recession may occur, especially with a thin, scalloped periodontium. The most predictable and expedient method of addressing an interproximal papilla deficit is to increase the gingival emergence of the adjacent restorations and/or moving the cervical contact point apically.

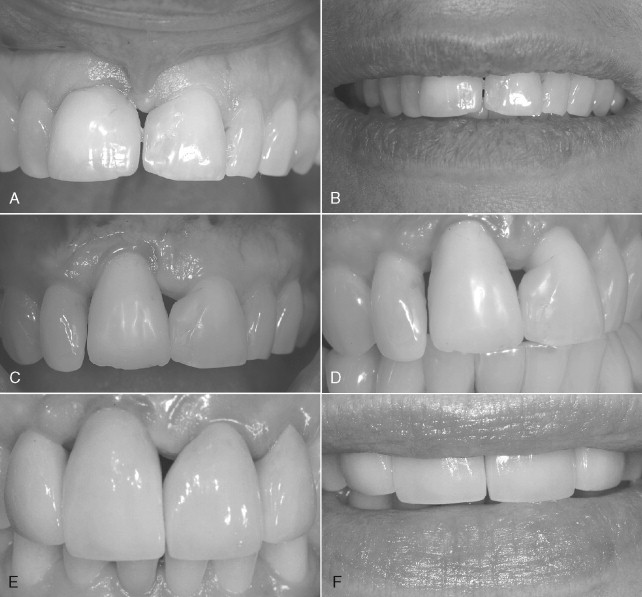

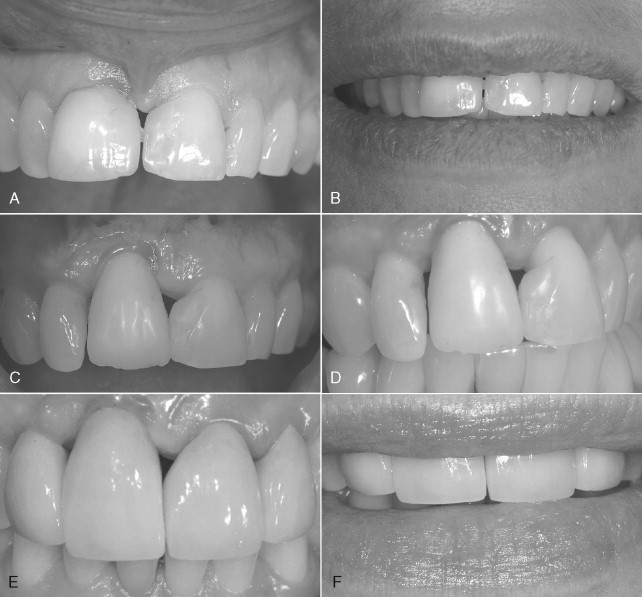

Another common problem with implant aesthetics, especially when replacing a single anterior tooth with an implant, is a discrepancy in crown heights, especially in the presence of a high lip line ( Figure 28-2 ). A useful resource to determine the appropriate aesthetic surgical procedure, if any, is the algorithm described by Kokich in a series of three articles on aesthetics and anterior tooth position. He notes that the most common crown length discrepancy with natural teeth occurs when one maxillary central incisor is shorter than the other, but the incisal edges are even. The problem can and should be anticipated before implant placement with proper diagnostic planning and establishment of patient expectations. If faced with the problem during the restorative phase the following options exist: (1) gingival surgery to correct soft tissue form or (2) intrusion and restoration of the shorter (natural) tooth.

Determination of the appropriate surgical technique is determined by periodontal probing of the labial sulci and measurement of the existing band of attached and keratinized tissue. If the incisal edges are even and cementoenamel junctions (CEJs) are level, a gingivectomy would be performed to remove the excess tissue. If a narrow band of attached tissue is present or there are differing bone heights, a flap procedure would be needed to allow for osseous recontouring ( Figure 28-2 ).

Kokich also describes preoperative planning and techniques to address problems with anterior tooth vertical positioning and mediolateral relationships. It should be noted that corrections usually involve orthodontics and restorative dentistry, not soft tissue surgical techniques.

▪

SOFT TISSUE AESTHETIC CONSIDERATIONS FOR IMPLANTS

Lack of aesthetics around implants can be a deficiency of several soft tissue factors, including color, contour, and consistency. Specific problems within these categories include loss or reduction of the interdental papilla, increased crown height, and exposure of implant margin. It is the author’s observation that many of these common problems arise during the restorative phase of treatment when surgical solutions are not possible, feasible, or well accepted by the patient. It therefore behooves the surgeon to understand and communicate to the patient any potential or preexisting aesthetic compromises that are present or may occur as a result of anatomic considerations. The patient’s expectations should be elucidated, recorded, and harmonious with those of the treating clinician.

Methods of communicating expectations of this sort use a nomenclature system, such as established by Palacci and Ericsson or Misch. The Palacci and Ericsson defect classification scheme is based on four classifications of vertical dimension and four classifications of horizontal dimension. The three-category classification system of Misch is of particular utility when discussing the anticipated appearance of the final restoration with patients. The system for fixed implant restorations classification divides the desired prosthesis into one of three categories: FP-1, FP-2, and FP-3. These options depend on the amount of hard and soft tissue replaced and serve to convey the appearance of the final prosthesis to all implant team members ( Table 28-1 ). Ridge deficiencies described by these systems are most frequently the result of a hard tissue deficiency, which should be addressed early in the treatment plan.

| Type | Definition |

|---|---|

| FP-1 | Fixed prosthesis; replaces only the crown; looks like a natural tooth. |

| FP-2 | Fixed prosthesis; replaces only the crown and a portion of the root; crown contour appears normal in the occlusal half, but is elongated or hypercontoured in the gingival half. |

| FP-3 | Fixed prosthesis; replaces missing crowns and gingival color and portion of the edentulous site; prosthesis most often uses denture teeth and acrylic gingival, but may be porcelain to metal. |

| RP-4 | Removable prosthesis; overdenture supported completely by implant. |

| RP-5 | Removable prosthesis; overdenture supported by both soft tissue and implant. |

Advanced diagnostic techniques, such as CT imaging, are useful to assess and quantify the need for hard and soft tissue support. Preliminary replacement of deficient hard tissues should be addressed before considering soft tissue augmentation. A ridge deficiency at the implant site should be corrected to within 3 mm of its optimal contour. Techniques for diagnosing and treating hard tissue defects are addressed in another chapter.

The likelihood of developing aesthetic complications is additionally based on tissue biotype. Tissue types have been categorized into two forms: thin and scalloped, or thick and flat. The stability of the osseous crest and position of the free-gingival margin are directly proportional to the thickness of the bone and gingival tissue. Kan et al. found that with implants, the level of the interproximal papilla of the implant is independent of the proximal bone level next to the implant, but is related to the interproximal bone level next to the adjacent teeth. He also found that even with ideal execution, facial and/or interproximal gingival recession may occur, especially with a thin, scalloped periodontium. The most predictable and expedient method of addressing an interproximal papilla deficit is to increase the gingival emergence of the adjacent restorations and/or moving the cervical contact point apically.

Another common problem with implant aesthetics, especially when replacing a single anterior tooth with an implant, is a discrepancy in crown heights, especially in the presence of a high lip line ( Figure 28-2 ). A useful resource to determine the appropriate aesthetic surgical procedure, if any, is the algorithm described by Kokich in a series of three articles on aesthetics and anterior tooth position. He notes that the most common crown length discrepancy with natural teeth occurs when one maxillary central incisor is shorter than the other, but the incisal edges are even. The problem can and should be anticipated before implant placement with proper diagnostic planning and establishment of patient expectations. If faced with the problem during the restorative phase the following options exist: (1) gingival surgery to correct soft tissue form or (2) intrusion and restoration of the shorter (natural) tooth.

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses