Cone-beam computed tomography provides orthodontists with 3-dimensional images of the craniofacial region and valuable information for diagnosis and treatment planning of craniofacial or dental anomalies. However, a narrow focus on the skeletal and dental contributions to malocclusion can cause failure to identify skeletal or soft-tissue pathologies of the craniofacial structures unrelated to the orthodontic concerns. Two cases are presented that demonstrate skeletal and soft-tissue anomalies identified as incidental findings on cone-beam computed tomography scans of asymptomatic orthodontics patients. One patient was diagnosed with craniofacial fibrous dysplasia; the other had an intrahemispheric lipoma. Their cone-beam computed tomography images are presented, along with a literature review on their pathologies.

Cone-beam computed tomography (CBCT) expands the imaging options for clinicians by providing volumetric information unobtainable with standard radiographs. This option is especially valuable in orthodontics, in which diagnosis is made in 3 planes of space. Along with the increased power to accurately diagnose malocclusion in 3 dimensions, CBCT imposes on clinicians an obligation to evaluate the entire imaged volume for pathology. Thus, clinicians using CBCT for diagnosis must have a strong knowledge of normal head and neck anatomy.

Although CBCT is most useful for imaging skeletal structures, soft tissues are also imaged, albeit at a lower contrast resolution. Orthodontists focused on diagnosing the skeletal and dental contributions to malocclusion might fail to recognize abnormalities in craniofacial structures captured in the CBCT images. To highlight the need to evaluate both the mineralized and soft-tissue components of CBCT images, we present 2 cases of incidental findings in the initial CBCT radiographs taken of orthodontics patients.

Patient 1: Fibrous dysplasia

A 12-year-old Hispanic girl came to the orthodontic clinic at the University of California at Los Angeles for screening. Her past medical history was significant for a lymphoma on the left side of the neck at age 3.5 years; it was surgically excised with no recurrence. The clinical examination showed a mild overbite and a slight asymmetry of the face. The patient was referred to the university’s Oral and Maxillofacial Radiology Clinic for panoramic, lateral cephalometric, and CBCT examinations.

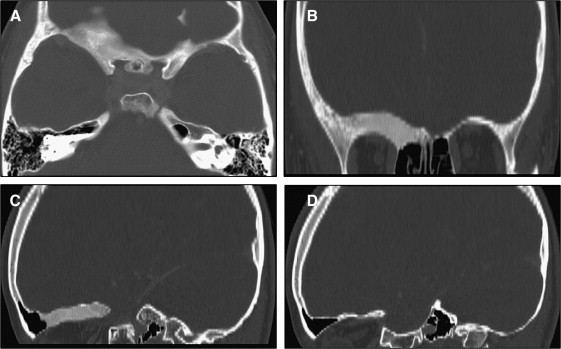

The lateral cephalograph was initially seen as normal, although in retrospect sphenoid opacification anterior to the sella turcica could be identified ( Fig 1 ). The CBCT images showed expansion and loss of cortication and trabecular architecture of the right frontal bone that extended to the lesser wing of the sphenoid. These changes, along with the ground-glass or homogeneous sclerotic appearance of this region, were consistent with fibrous dysplasia ( Fig 2 ).

The patient was referred for medical computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain. Consistent with the CBCT findings, the medical computed tomography image showed fibrous dysplastic changes of the roof of the right orbital fossa and the superior margin of the greater wing of the sphenoid. There was no reduction in the diameter of the right optic nerve root foramen or the superior orbital fissure ( Fig 3 ).

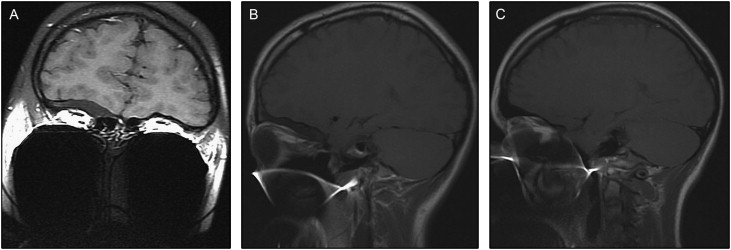

MRI scans of the brain and orbits with contrast were carried out to assess the optic nerve canal. There were hyperostotic changes to the roof of the right orbit and lesser wing of the sphenoid bone. There was no obvious compromise to the optic nerve as it transited the canal, and the brain was normal ( Fig 4 ). (Because of the fixed orthodontic appliances, substantial phase artifacts obscured the tail of the orbital fossa.)

The patient was referred to an ophthalmologist to complete the evaluation. Since the lesion was asymptomatic and growing slowly, no treatment was indicated. Radiographic follow-up in 6 months was recommended. A CBCT scan was done to assess the progression of the lesion. No significant changes were observed between the 2 examinations. The patient is followed annually with CBCT imaging to monitor the progression of her disease.

Patient 2: Intrahemispheric lipoma

A 16-year-old white boy came to the same orthodontic clinic for screening. His medical history was unremarkable. Panoramic and lateral cephalometric radiographs, full-mouth series, and CBCT scans were obtained.

The bones of the skull, face, soft tissues, airway, and paranasal sinuses were unremarkable on the lateral cephalometric radiograph ( Fig 5 ). However, the CBCT examination showed a well-defined uniform radiolucency measuring approximately 9 × 17 mm in the right side of the temporal lobe of the brain ( Fig 6 ).