This review highlights what is known regarding differences in tooth loss by sex/gender, and describes: gender-related tooth ablation (the deliberate removal of anterior teeth during life) found in skulls from history and prehistory; potential mediators of the relationship between sex/gender and tooth loss; the current epidemiology of gender differences in tooth loss (limited to North America); and risk factors for tooth loss in the general population and in women.

Key points

- •

Across history and prehistory into the present day, sex and gender have played, and are likely to continue to play, major roles in differences in dental disease rates, and in the prevalence of tooth loss and edentulism.

- •

An anthropologic perspective on tooth loss is valuable to clinical dentistry because it provides evolutionary, prehistoric, and ethnographic contexts for understanding an important aspect of oral health in modern humans.

- •

Whereas in many populations across the world women most certainly had, and continue to have, higher rates of tooth loss and edentulism, differences in tooth loss by sex/gender are likely decreasing in North America.

- •

The relationship between sex/gender, dental disease, and tooth loss is inherently very complex; it seems likely that both biology and social factors associated with being female are important risk factors for tooth loss.

The retention or loss of permanent teeth is of central importance to an individual’s oral health status and to quality of life. The loss of some or all teeth from the permanent dentition is closely associated with myriad dental and metabolic diseases and has multiple causes, including both systemic biological and cross-cultural behavioral etiology. Tooth loss as a measure of oral health has several advantages over other oral health and disease indices, including not only its direct associations with oral function and with overall health and well-being but also the ease by which the presence or absence of teeth can be measured. Sex and gender influence oral disease, including caries and periodontal diseases, and result in differences in tooth retention rates, edentulism, and in the incidence of tooth loss.

Tooth loss is influenced by biology and genetics, but is also a key indicator of dental care utilization and access (ie, teeth are “lost” mainly because someone extracts them), and is inherently associated with culture and attitudes, including patients’ and dentists’ philosophies of dental care. Indeed, it is a grave error to dismiss the importance of “the complex pattern of roles, responsibilities, norms, values, freedoms, and limitations that define what is thought of as ‘masculine’ and ‘feminine’ in a given time and place” in influencing health. This article follows the convention of referring to differences by sex and gender as sex/gender differences, but when speaking solely of biological differences between men and women the authors use the word sex, and when speaking only of differences resulting from the cultural construction of male/female roles, the word gender is used. Differences in oral health are a function of differences in biology (sex) but also of differences in cultural context (gender).

The purposes of this article are:

- 1.

To provide relevant anthropologic and historical background on sex/gender differences in tooth loss

- 2.

To discuss the recent epidemiology of tooth retention and loss, focusing on North America, in the context of sex/gender differences and similarities

- 3.

To elucidate ways in which biology (sex) and culture (gender) are likely to influence differences in tooth retention, tooth loss, and edentulism

Sex/gender differences in tooth loss: an anthropologic perspective

An anthropologic perspective on tooth loss is valuable to clinical dentistry because it provides evolutionary, prehistoric, and ethnographic contexts for understanding an important aspect of oral health in modern humans. This discussion of tooth loss focuses on “dental ablation” and adopts a bidirectional uniformitarian approach: the present informs us about the past; however, knowledge of the past provides a broad comparative context for understanding tooth loss and dental ablation in modern humans.

In anthropological terms, antemortem tooth loss (AMTL) is defined as “loss of teeth during life, as evidenced by progressive resorption of the alveolus,” and differs from tooth ablation, which is defined as “… the deliberate removal of anterior teeth during life.” Tooth ablation is a form of intentional dental modification that is commonly grouped with other forms of tooth modification, such as chipping, filing, inlays, and bleaching. The etiology of AMTL and ablation is complex and multicausal.

In prehistory, skeletal series present unique challenges in the differential diagnosis of causal factors leading to loss of teeth before death. It should be noted that distinguishing the culturally mediated practice of tooth ablation from numerous other causes of tooth loss can be difficult, but this issue has a long history. It has been suggested that 7 criteria may be used for the recognition of ritual ablation: (1) no evidence of dental disease, (2) symmetry or near symmetry of tooth loss, (3) repetition of similar pattern of tooth loss in the group, (4) fracture of the labial wall of the alveolar bone, (5) indication that the tooth loss occurred in youth, (6) presence of the practice in neighboring or related groups, and (7) mention of the practice in myths and legends. However, some have criticisms for each of these criteria, contending that a highly irregular pattern of loss contrasts sharply with the highly regular practices of tooth removal documented ethnographically in some African groups.

Although a comprehensive discussion of tooth ablation and AMTL in nonhuman primates is beyond the scope of this report, it should be noted that tooth loss is well documented in the fossil record of many ancestral species. A key example is the “old man” from La Chapelle aux Saints, a Neanderthal fossil that figured prominently in early misunderstanding the Neanderthal’s significance in human evolution. The nearly edentulous skull of Homo erectus (= ergaster ) from the site of Dmanisi (about 1.77 million years ago) is probably male and retained only one tooth: the left mandibular canine. This find renewed the debate over how far into the past modern human social structure, life history, care, and compassion may have existed. Some believe that in antiquity, individuals with extensive edentulism must have benefitted from altruistic care and assistance to survive in the absence of a functional dentition. Others, citing edentulism in nonhuman primates, assert that survival with severe masticatory impairment can be present in the absence of “human-like” caring and cooperative behavior.

Sex/gender differences in tooth loss: an anthropologic perspective

An anthropologic perspective on tooth loss is valuable to clinical dentistry because it provides evolutionary, prehistoric, and ethnographic contexts for understanding an important aspect of oral health in modern humans. This discussion of tooth loss focuses on “dental ablation” and adopts a bidirectional uniformitarian approach: the present informs us about the past; however, knowledge of the past provides a broad comparative context for understanding tooth loss and dental ablation in modern humans.

In anthropological terms, antemortem tooth loss (AMTL) is defined as “loss of teeth during life, as evidenced by progressive resorption of the alveolus,” and differs from tooth ablation, which is defined as “… the deliberate removal of anterior teeth during life.” Tooth ablation is a form of intentional dental modification that is commonly grouped with other forms of tooth modification, such as chipping, filing, inlays, and bleaching. The etiology of AMTL and ablation is complex and multicausal.

In prehistory, skeletal series present unique challenges in the differential diagnosis of causal factors leading to loss of teeth before death. It should be noted that distinguishing the culturally mediated practice of tooth ablation from numerous other causes of tooth loss can be difficult, but this issue has a long history. It has been suggested that 7 criteria may be used for the recognition of ritual ablation: (1) no evidence of dental disease, (2) symmetry or near symmetry of tooth loss, (3) repetition of similar pattern of tooth loss in the group, (4) fracture of the labial wall of the alveolar bone, (5) indication that the tooth loss occurred in youth, (6) presence of the practice in neighboring or related groups, and (7) mention of the practice in myths and legends. However, some have criticisms for each of these criteria, contending that a highly irregular pattern of loss contrasts sharply with the highly regular practices of tooth removal documented ethnographically in some African groups.

Although a comprehensive discussion of tooth ablation and AMTL in nonhuman primates is beyond the scope of this report, it should be noted that tooth loss is well documented in the fossil record of many ancestral species. A key example is the “old man” from La Chapelle aux Saints, a Neanderthal fossil that figured prominently in early misunderstanding the Neanderthal’s significance in human evolution. The nearly edentulous skull of Homo erectus (= ergaster ) from the site of Dmanisi (about 1.77 million years ago) is probably male and retained only one tooth: the left mandibular canine. This find renewed the debate over how far into the past modern human social structure, life history, care, and compassion may have existed. Some believe that in antiquity, individuals with extensive edentulism must have benefitted from altruistic care and assistance to survive in the absence of a functional dentition. Others, citing edentulism in nonhuman primates, assert that survival with severe masticatory impairment can be present in the absence of “human-like” caring and cooperative behavior.

Tooth loss in prehistory

Teeth may be missing from the dental arch for many reasons, a situation that makes accurate diagnosis of the exact cause of tooth loss difficult in any population. However, the prime cause of AMTL in prehistoric skeletal series is dental disease. While periodontal disease and dental caries have been recognized as the major reasons for AMTL in archaeological samples, severe dental wear and dental trauma also contribute significantly to AMTL. Although sex/gender differences in AMTL from oral diseases are often significant (caries and tooth loss being more common in women than in men), differences in tooth ablation are primarily influenced by culturally mediated behavior and exhibit significant variation by sex and gender, both temporally and regionally. Moreover, although ablation may account for a smaller percentage of teeth lost antemortem than disease, this practice is the focus of intense study by anthropologists because of its global distribution, the diverse sociocultural settings, and the wide range of behaviors with which it is associated. Ablation has been practiced on every continent, from Neolithic to modern times, and may reflect social status, rites of passage (puberty/initiation, marriage), or mourning the death of leader, relative, or loved one.

Tooth ablation was, in many cases, more common in one gender than in the other: for example, the observed variation in anterior tooth loss in circum Arctic populations may have resulted from trauma due to a strenuous lifestyle, and gender-specific use of teeth as tools in subsistence and craft activities. Additional salient examples of ablation are shown in Table 1 . Ablation has been documented in prehistory from sites in circum Mediterranean North Africa, and more extensively in sub-Saharan Africa. Ablation was also practiced more than 10,000 years ago by prehistoric people of the Maghreb, North Africa, and has been documented geographically and chronologically to reveal changing patterns of ablation. The investigators interpret the decreasing frequency of ablation over time, the changing pattern of ablation by sex, and differences in the regional and cultural distribution of the practice as indicating the diversification of social meaning. Prehistoric Southeast Asia provides clear evidence of cultural modification of teeth, such as filing and ablation, which are distinct from congenitally missing teeth in prehistoric samples from Thailand. Patterns of ablation changed over time: early burials were missing mainly maxillary lateral incisors, whereas in later-phase burials maxillary central and all mandibular incisors were missing. Sex differences in missing teeth were not significant in early burials, but females were missing more teeth than males in later-phase burials.

| Continent | Era | Gender Relationship | Ablation Pattern | Proportion of Sample Affected |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Africa | Iberomarusian Period (>20,000 bp to at least 10,000 bp ) | Both genders affected, but males > females (average of 6.6 teeth vs 6.3 teeth) | Limited to the upper central incisors | Ablation nearly universal |

| Africa | Transitional Epipaleolithic Period | Genders equally affected | Minimally involving the lower incisors, involving all 8 incisors roughly half the time | Ablation nearly universal |

| Africa (Eastern Algeria and Tunisia) | Capsian period (9800 bp ) | Females > males (88% vs 38%) | Ablation in 62% of the sample | |

| Africa | Neolithic period | No data | Ablation in 27% of the sample, suggesting a reduction in frequency of this practice | |

| Africa (Sudan) | 350 bp to ad 1400 | Genders equally affected (males 12.2%, females 13.3%), adults only | Mandibular central, lateral incisors removed in symmetric or asymmetric patterns | Ablation in 9.4% of the sample |

| Africa (South Africa) | Early Iron Age (ca 1500 bp ) | Genders equally affected, same mean age at ablation (males = 15.6 y; females = 16.6 y), ablation occurred across a wide range of ages (11–20 y) | Missing teeth were said to symbolize gang initiation or membership and to enhance the pleasure of oral sexual acts | |

| Asia (southeast Thailand) | 4000–3500 bp | Sex differences in missing teeth not significant in early burials, but females were missing more teeth than males in later-phase burials | Various, involving anterior teeth. Patterns changed over time: early burials missing mainly maxillary lateral incisors, later burials missing maxillary central incisors, mandibular incisors | |

| Asia (northwestern Cambodia) | 2500–1500 bp | No sex differences were found in number of teeth ablated in maxillae or in mandibles, by site or in the composite | The majority of specimens (83.5% maxilla; 61.1% mandible) exhibited a symmetric pattern of ablation. Filing of anterior teeth was also documented at both sites | |

| Asia (northeastern Thailand) | ca 200 bp to ca ad 500 | Males tended to exhibit missing lateral incisors more often than females, but the difference was not significant | Most frequent pattern involved missing all 4 lateral incisors | 79% were congenitally missing at least 1 upper or lower lateral incisor |

| Asia (Japan) | 18,000 bp | Evidence of missing lower central incisors and alveolar remodeling a female specimen | ||

| Asia (Japan) | Jomon period (14,000 to about 300 bp ) | Males | Upper canines were the principal teeth extracted and indicators of skeletal development (epiphyseal fusion) suggest ablation began at 12–13 y | 80%–100% |

| Asia (China) | Dawenkou Neolithic (6500 bp ); practice declines suddenly with the onset of the Longshan culture (4000 bp ) a | No sex difference | Targeted maxillary incisor and canine teeth normally commenced in early adolescence, or ca 13–15 y | 60%–90% |

a Period of prevalence and subsequent decline of ablation 2000 years earlier than Japan.

An extensive literature on ritual tooth ablation in East Asia focuses on the history, patterns, methods, prevalence, and significance of this widespread practice. Presence of broken roots and root fragments in the alveolar bone of Jomon period males from Tsukumo and Yoshigo suggests that a traumatic method of ablation was common. A comparison of the antiquity and temporal transition in ablation customs in China and Japan reveal differences in the earliest evidence, height of prevalence, and decline in the practice of ablation. The period of prevalence and subsequent decline of ablation in China occurred 2000 years earlier than in Japan, although the type and significance of ablation diversified through time in both countries.

In China, removal of maxillary lateral incisors was the earliest form of tooth ablation and was the principal type practiced until recent times. Indicating attainment of adult status, ablation may also have signified eligibility for marriage and in some areas may indicate clan membership, allowing enforcement of interclan marriage rules. In Japan, a significant increase in the types of ablation through time and across the life span implies an increase in diversification of social meaning. For example, removal of upper canines was associated with adult status, extraction of lower incisors and canines occurred at marriage, and removal of first premolars was a sign of mourning. Different types of ablation have also been interpreted to signify different places of origin. In a significant number of burials, the husband, who had 4 canines removed, was buried in association with his wife, who had maxillary canines and 4 lower incisors removed. Thus, rules of postmarital residence (bilocal, uxorilocal) have been inferred from ablation types in Jomon period Japan, although regional variation (eastern, western) is likely. This interpretation is controversial, and recent research using stable-isotope analysis of diet and biodistance estimates from cranial and dental measurements challenge these earlier theories of social meaning. Persons with ablation of 4 canines appear to have been more dependent on terrestrial dietary resources; conversely, persons with ablation of maxillary canines and 4 lower incisors were more reliant on marine resources. Furthermore, ablation type was unrelated to migratory pattern, but may represent kin-based social units whereby achievement, status, or age were criteria for membership.

Tooth ablation in the modern world

Tooth ablation is still practiced among diverse ethnic groups in Africa, where it has a long history and a wide range of ritual and practical motivating factors, and poses significant challenges among emigrants to other cultures where ablation is unknown and not practiced. For example, ablation of anterior teeth continues among ethnic groups of southern Sudan and Ethiopia. Although mandibular incisor and canines are most frequently removed, anywhere from 2 to 6 mandibular or maxillary teeth may be removed in association with achieving adulthood, enhancing aesthetics, emitting special linguistic sounds, indicating tribal membership, or consuming soft or liquid foods. In Africa, and among some children of African parents living in other parts of the world, there has been a tradition of extirpation of deciduous tooth buds by village healers to rid the child of perceived “tooth worms,” a practice called infant oral mutilation.

In South Africa, tooth ablation is currently practiced among urban groups of the Western Cape. Two novel motivations for ablation were uncovered in this group; missing teeth were said to symbolize gang initiation or membership and to enhance the pleasure of fellatio. Although some Cape Flats groups refer to the interdental space resulting from ablation as a “passion gap,” some researchers refute this motivation as an incorrect and insulting myth, but regard the importance of gang activity and membership a more likely explanation for the “Cape Flats smile.”

Whereas an edentulous space or interdental gap in these groups has well-established significance and value, among most European and American groups tooth loss is considered unattractive and is associated with poor standards of health, low socioeconomic status, and a lack of education. Immigrants from ethnic groups practicing tooth ablation often quickly appreciate the difference in cultural meaning associated with missing teeth, and seek dental restoration as a means of improving social acceptance, facilitating articulation and pronunciation of certain standard English sounds, and enhancing food-acquisition ability.

Prenuptial edentulism and dowry dentures

There are several references to gender-based tooth extractions in the current medical and dental literature. In some regions of the world there appears to be persistence of an old tradition of removing all of a young woman’s teeth when she approaches a marriageable age. This practice, called prenuptial edentulism, seems to be related to a wish for attractive teeth, or so-called dowry dentures.

Prenuptial edentulism was first described in the Guatemala highlands, where dental disease was rampant, dental care was expensive for villagers, and young women were perceived to be less tough than young men, hence family resources were spent on extractions for girls rather than for boys. In this poor rural population, some young women would inherit their grandmother’s dentures. This practice has also been documented among rural Acadian and French-Canadian populations, where some young women would have their maxillary teeth, or all of their teeth, removed before marriage in order to be fitted for dentures, regardless of their current dental health. In one area of Maine, adjacent to the Canadian region where the practice was described, a local dentist reported that dowry dentures are a common high-school graduation gift for Acadian girls.

In several areas of England, dentists have reported full-mouth clearance and subsequent dentures as a wedding gift, especially for women. In his 1980 valedictory address, British Dental Association President D.G.E. Roberts described the practice: “I can recall that, in certain parts of the country, one of the most popular gifts to a young woman intending marriage was to enable her to have her teeth extracted and dentures fitted. Thus the dread of toothache was removed and the future partner spared any trouble and expense.”

Sex/gender differences in the distribution and determinants of tooth loss in modern times: North America

As is the case in history and prehistory, tooth loss in modern humans often differs by sex/gender and by etiology. In general, a higher prevalence of both tooth loss and dental caries has been documented among women than among men in many parts of the world. Because most teeth are extracted because of caries, it would follow that rates of tooth loss would reflect rates of dental caries, hence the predisposition for women to be more affected than men by this disease. However, because sex/gender differences in tooth loss reflect not only sex/gender disparities in levels of dental disease but also differences in socioeconomic factors, personal and cultural attitudes and beliefs regarding teeth and dental care, and the availability, frequency, and use of both episodic and preventive dental care, the relationship between sex/gender and tooth loss is quite complex.

In the United States, there are few data specific to sex/gender differences in the prevalence of tooth loss prior to the National Health Survey of 1960 to 1962. However, in that report, tooth loss in adults was common (overall, 18% of adults were completely edentulous), and that the prevalence of tooth loss increased dramatically in persons older than 45 years. Part of this dramatic increase was likely due to a lack of preventive dental care for children and adults in the early part of the century, which would have affected all but the youngest group of adults, as well as the popularity of the concept of diseased teeth as foci of infection responsible for a host of systemic diseases. Extraction of teeth for the sake of systemic health continued into the 1950s and, though it is likely that some of the tooth loss seen in older adults because of this cohort effect could be seen in studies of adult oral health extending into the later part of the twentieth century, the effect of the concept of focal infection on sex/gender disparities in tooth loss is unknown. One might hypothesize that perhaps sex disparities in rates of diseases thought to be caused by infected teeth (ie, rheumatism, depression) were higher in women than in men, or that more frequent use of both general and dental services by women might have accounted for these differences. What is absolutely apparent, however, is that as early as the National Health Survey of 1960 to 1962, women were more likely than men to be edentulous (19.6% vs 16.4%), and this sex/gender disparity was true for each of the 7 age groups represented in the sample. In Canada from 1970 to 1972, women were more likely than men to be edentulous in all age categories; the largest differences were seen after the age of 30, with 22.9% of women versus 6.1% of men age 30 to 39, 26.5% of women versus 18.0% men age 40 to 49, 38.4% of women versus 30.4% of men age 50 to 59, and 55.7% of women versus 49.5% men age 60 years and older being edentulous.

Rates of tooth loss and edentulism decreased in North America during the latter half of the twentieth century, when the preventive dentistry movement began. Disease rates have been affected by water fluoridation, the pervasive use of topical fluoride in dentifrices and mouth rinses, and the change in the culture of dentistry to emphasize retention of teeth. In the United States between 1988 and 1994, when the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) was conducted, and from 1999 to 2004, the most recent NHANES survey in which a dental examination was performed, rates of edentulism among adults have continued to decline, from 6% to 4%. In Canada, in 1970 to 1972, 23.6% of adults aged 19 or older were edentulous; by 2007 to 2009 the proportion had dropped to 6.4% edentulous overall.

Table 2 provides a summary of adult and older adult population-based epidemiologic studies performed in the United States and Canada over the past 25 years that have included data broken down by sex/gender. It is clear that disparities in rates of edentulism by gender have virtually disappeared, with some notable exceptions. In Canada, although rates of edentulism are now similar between men (6.3%) and women (6.5%), women are still more likely to have lost at least 1 tooth (46.7% vs 38.1%). In the United States, there are large and persistent racial and ethnic disparities in oral health; data from the Hispanic Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (HHANES, 1987) demonstrated that among Mexican Americans, 5.2% of females versus 3.5% of males were edentulous. It appears that in recent years, sex/gender differences in edentulism among whites have disappeared. However, among blacks and Hispanics, women are still more likely than men to have missing teeth, although it has been shown that women have higher rates of caries and men more frequently have periodontal disease. These differences in disease patterns likely involve behavioral factors (including diet, smoking, patterns of health-protecting behaviors such as oral hygiene practices and dental treatment patterns), but certainly biology is an important contributor to disease rates; specifically, women’s reproductive function, including demands of menses, pregnancy, and parity.

How sex/gender may influence rates of tooth loss

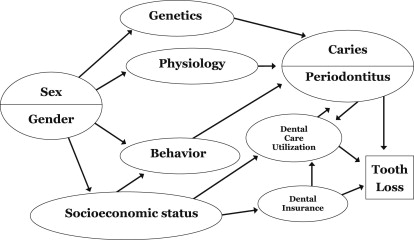

Fig. 1 provides a conceptual model of how sex (biology) and gender (sociobehavioral factors) are likely to influence rates of tooth loss. Relationships between the variables in this conceptual model are complex, and this conceptual framework is necessarily simplified for the sake of clarity. This model does, however, recognize the multifactorial nature of both dental disease (caries and periodontitis) and tooth loss, demonstrating that both sex (genetics, physiology) and gender (the constructed social roles of what it is to be male or female) are important contributors to caries and periodontal diseases, and to tooth loss. In this model several variables mediate the relationship between gender and dental disease; gender is related to behavior (eg, oral hygiene behavior and oral health protective and damaging behaviors such as smoking and diet), which is in turn related to caries and periodontitis. Gender is also related to socioeconomic status variables such as income, education, and occupation, which are related to dental care use and dental insurance. These dental-related factors are in turn related to caries and periodontitis; and, conversely, having dental disease alters patterns of dental care use. In addition, there may in some cases be either a synergistic or antagonistic effect of gender-related and sex-related factors that may increase or decrease rates of disease or tooth loss. For example, changing hormone levels throughout life related to women’s reproductive function (including demands of menses, pregnancy, and parity) are likely to affect the periodontium, sometimes in irreversible ways. Destruction of the periodontium, in turn, influences whether teeth are retained or extracted. However, women and men have different patterns of dental utilization that are likely to affect whether teeth are extracted or not. Although it is difficult to say with certainty whether biology or society/culture more profoundly influences levels of dental disease (caries, periodontitis) and tooth loss, most would argue that both factors together are important in the pathway toward tooth loss. The specific contributions of sex-related and gender-related factors to different levels and rates of disease, and to tooth retention and loss, are further discussed here.

Sex-Related Factors Influencing Tooth Loss

While much of human biology is shared between the sexes, there are important sex-related differences. First, because tooth loss is irreversible and cumulative, tooth loss is necessarily associated with increased age. Indeed, it is clear from many studies that the most important risk indicator for partial and complete edentulism is age. Women experience lower mortality rates from most of the major causes of death, including heart disease, cancer, respiratory disease, accidents, suicide, and homicide, and women in the United States currently live on average about 5 years longer than men, almost to age 81 years, whereas women in Canada live about 4.5 years longer than men, to age 83 years. Although some have proposed that perhaps women experience more tooth loss simply because they live longer, when well-conducted studies adjust for differing age structures between population subgroups, including those by sex/gender, differences tend to be attenuated, but not absent.

Given that differing life expectancies do not completely account for differences in rates of tooth retention and loss, other factors are likely involved. What biological differences between women and men could contribute to differences in tooth loss? The most obvious difference between the sexes is hormonal: women have a different mix of reproduction-related hormones in comparison with men, and most women are likely to experience pregnancy and lactation, often multiple times in their lives. Hormonal variations have been demonstrated to affect oral health. In particular, the intraoral soft-tissue changes that accompany pregnancy, as a result of the complex physiologic alterations, are well documented. Fluctuations of sex hormones during pregnancy increase oral vasculature permeability, decrease host immunocompetence, and alter levels of oral bacteria, thereby increasing susceptibility to oral infection, including periodontal disease. Gingivitis is almost universal during pregnancy, and progression of periodontitis during pregnancy has been documented. Although the popular belief that pregnancy weakens teeth as a result of calcium depletion is an unsupported hypothesis, studies have shown that increased childbearing (parity) is related to tooth loss, possibly through increased hormonal fluctuations that occur because of multiple pregnancies. In addition to hormonal changes that occur during pregnancy, monthly hormonal fluctuations in menses are thought to play a role in gingival inflammation in women, and in fact may exaggerate preexisting inflammation in gingival tissues. There is also evidence that menopause and accompanying osteoporosis are related to periodontitis and tooth loss, and conversely that the use of hormone-replacement treatment has been associated with a reduced likelihood of edentulism. These results suggest the potential for a protective role of estrogen and progesterone on oral health.

Additional biological differences between the sexes are likely related to dental caries, which persists in most areas of the world as the most common reason for tooth extractions. In most adult populations, including the United States and Canada, rates of dental caries have been shown to be higher in women. Biological factors that influence the development of caries include salivary flow and sex-linked genetic susceptibility. Saliva protects teeth from dental caries by several mechanisms, including its cleansing effects and its ability to buffer acids produced by dental plaque. Compared with men, women have lower stimulated and unstimulated salivary flow rates and secrete less salivary immunoglobulin A, and menopause is associated with xerostomia. It has been suggested also that hormonally related changes in eating patterns, salivary composition, and salivary flow rates are related to a higher rate of caries in females.

In addition, immune diseases that affect salivary flow disproportionately affect women. For example, Sjögren syndrome, which affects about 3% of older women, has an overwhelming preponderance of female patients. Several recent studies have demonstrated that periodontal patients have higher rates of rheumatoid arthritis, a disease with a gender bias toward women. It is not clear whether the diseases are simply associated because of shared risk factors and similarities in host response, or whether periodontal pathogens predispose to rheumatoid arthritis in conjunction with other environmental and genetic factors.

Recent studies suggest that a sex-linked gene may explain, to some extent, why rates of dental caries may be higher in women. These genes, Amelogenin X (found on the X chromosome) and Amelogenin Y (on the Y chromosome), code for proteins that constitute 90% of the enamel matrix. Although genetic research on caries is yet in its infancy, and genetic and other biological factors that may contribute to gender discrepancies in tooth loss clearly require much more investigation, 2 recent studies in children have supported an association between Amelogenin X and experience of high caries. Ultimately, genetic differences may prove to be just as, or more important than, environmental factors in the development of dental caries.

Gender-Related Factors Influencing Tooth Loss

Factors related to tooth loss that are associated with societal gender roles include health-damaging or health-promoting behaviors, such as smoking, diet, and oral hygiene (eg, flossing). Smoking has long been seen as a risk factor for periodontal disease and tooth loss, and rates of smoking typically vary by gender, with higher rates of tobacco use in men, but with large variations of male/female differences in smoking rates by country and culture. Studies that analyze data by sex/gender subgroup, and studies limited to women confirm that smoking is a risk factor for periodontal disease and tooth loss among women.

Tooth loss, diet, and nutrition are an important triad, given that mastication of food is a primary function of human dentition. Women and men have been found to have different dietary intakes largely attributed to different energy needs, as well as food preference and belief differences. Hence, it would make sense that there might be differences between men and women in the association between tooth loss/edentulism and nutrient intake. Indeed, some researchers have found that nutrient intakes in older persons decreased with impaired dentition status, controlling for age and smoking; in addition, fiber, vitamin, and mineral intake were inversely correlated with masticatory function. Investigators using data from the general United States population (NHANES 1999–2002), however, found similarities in dietary components, although the most reduced components of diets for edentulous persons were fruits for both men and women, and vegetables for women. These data translated as lower α-carotene and β-carotene levels in edentulous males and lower vitamin C levels in females. Edentulous women were also lower on their overall healthy diet scores than their dentate counterparts. Other components of the diet have been found to be related to tooth loss: a recent prospective study found that dietary dairy calcium intake seemed to protect against future tooth loss in both men and women. Another prospective study found that women who had previously changed their diet to one comprising significantly higher intakes of saturated fat, trans fat, cholesterol, and vitamin B 12 , and lower intake of polyunsaturated fat, fiber, carotene, vitamin C, vitamin E, vitamin B 6 , folate, potassium, vegetables, and fruits (in other words, a diet predisposing to the development of cardiovascular disease) lost more teeth than women with healthier diets.

In the United States and many other countries, gender is also linked to socioeconomic status, with women, in comparison with men, having less wealth, lower incomes, reduced or underemployment, and, in some cases (but notably not in present-day North America), less education. Socioeconomic status has been inexorably linked to dental disease and tooth loss, with large disparities in dental disease and tooth loss rates evident in both developed and developing countries. Income and wealth are closely related to the ability to pay for dental care and to the kind of dental care (ie, preventive vs symptomatic), especially in countries where dental insurance is rare or nonexistent. Therefore, one might assume that men use health care to a greater extent than do women, because of their income and wealth. However, studies on utilization of both medical and dental care show consistently that women are more likely to visit a health care provider than are men, and are more likely to access preventive care, including preventive dental care. However, as is true in the general population, disparities among women in rates of dental care use have been reported in relation to socioeconomic status, race/ethnicity, and dental insurance status.

Finally, differences by gender regarding oral health habits, as is the case with healthy general health habits, have been found consistently in favor of females, including brushing and flossing. Longitudinal studies have verified the importance of oral hygiene as related to tooth loss and dental disease. Consistently, women appear to brush and floss more frequently than men. A recent investigation found that gender differences in gingivitis could be explained by oral health behaviors and hygiene status, which were in turn influenced by lifestyle, knowledge, and attitude.

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses