Although in the United States the incidence of oral and pharyngeal cancer (OPC) has been significantly higher in men than in women, the identification of human papilloma virus as a risk factor for OPC has focused new scrutiny on who may develop OPC. One surprising element is that non-Hispanic white women have a higher incidence of OPC than of cervical cancer. OPC is thus a woman’s disease, and diligence is needed to ensure that the occurrence of OPC in women does not go undetected by their oral health care providers.

Key points

- •

Incidence rates of oral and pharyngeal cancer (OPC) are lower in women than in men.

- •

Incidence rates of OPC among women, at least among some subgroups and sites, are increasing.

- •

Among non-Hispanic White women, the incidence rates of OPC have been higher than those of cervical cancer for at least the past decade.

- •

Susceptibility to OPC for women versus men, given the same risk behaviors, is inconclusive, although some studies suggest that women have a greater susceptibility.

- •

Cancer of the oral cavity and pharynx is also a woman’s disease.

Descriptive epidemiology

Oral and pharyngeal cancer (OPC) is a significant global health problem, with approximately 480,000 new cases diagnosed every year globally; of these, approximately 35,000 to 40,000 new cases occur in the United States. Women comprise 147,000 of the new cases globally and 10,000 of the new cases in the United States. Incidence estimates for 2012 are slightly increased to 11,710 newly affected women. Based on data from the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) database (2005–2009), the median age at diagnosis is 62 years. About 6% of the patients are between 35 and 44 years, and the incidence rate increases with increasing age. Worldwide the incidence rates vary, based on the regional prevalence of risk factors such as use of tobacco, alcohol, and/or betel quid. The rates among women are lower when compared with men; however, recent trends show an increase in the incidence among women. In 1950, the male to female ratio was 6:1 but by the year 2002 the gap had closed to a ratio of 2:1.

For the newly diagnosed patient with OPC, the effect is detrimental to both quality of life and survival ( Table 1 ). More than 79,000 women die every year globally as a result of OPC, with approximately 2400 annual female deaths in the United States. Based on mortality statistics from 2005 to 2009, the age-adjusted death rate was 2.5 per 100,000 men and women per year. The average 5-year survival rate of 50% has not changed significantly in the last 3 decades. Surviving the disease depends, among other factors, on the clinical stage at diagnosis. Based on SEER data from 2002 to 2008, the average 5-year survival exceeds 85% if diagnosed early, drops to 57% if the cancer presents with regional stage (spread to regional lymph nodes), and further decreases to 35% when the cancer has metastasized (distant stage).

| Cancer | Incidence | Mortality | 5-Year Prevalence | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | (%) | ASR (W) | N | (%) | ASR (W) | N | (%) | Proportion | |

| Women | |||||||||

| World | |||||||||

| Lip, oral cavity | 92524 | 1.5 | 2.5 | 44545 | 1.3 | 1.2 | 209581 | 1.4 | 8.5 |

| Nasopharynx | 26589 | 0.4 | 0.8 | 15625 | 0.5 | 0.4 | 68975 | 0.5 | 2.8 |

| Other pharynx | 28034 | 0.5 | 0.8 | 19092 | 0.6 | 0.5 | 59008 | 0.4 | 2.4 |

| United States | |||||||||

| Lip, oral cavity | 7355 | 1.1 | 2.8 | 1411 | 0.5 | 0.4 | 23372 | 1.1 | 18.4 |

| Nasopharynx | 565 | 0.1 | 0.3 | 186 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 1640 | 0.1 | 1.3 |

| Other pharynx | 2077 | 0.3 | 0.8 | 784 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 5173 | 0.3 | 4.1 |

| Men | |||||||||

| World | |||||||||

| Lip, oral cavity | 170496 | 2.6 | 5.2 | 83109 | 2.0 | 2.6 | 401075 | 3.0 | 16.3 |

| Nasopharynx | 57852 | 0.9 | 1.7 | 35984 | 0.9 | 1.1 | 153736 | 1.1 | 6.3 |

| Other pharynx | 108588 | 1.6 | 3.4 | 76458 | 1.8 | 2.4 | 229030 | 1.7 | 9.3 |

| United States | |||||||||

| Lip, oral cavity | 15817 | 2.1 | 7.3 | 2435 | 0.8 | 1.1 | 52326 | 2.4 | 43.2 |

| Nasopharynx | 1352 | 0.2 | 0.7 | 415 | 0.1 | 0.2 | 4094 | 0.2 | 3.4 |

| Other pharynx | 8144 | 1.1 | 3.9 | 2359 | 0.8 | 1.1 | 21536 | 1.0 | 17.8 |

Descriptive epidemiology

Oral and pharyngeal cancer (OPC) is a significant global health problem, with approximately 480,000 new cases diagnosed every year globally; of these, approximately 35,000 to 40,000 new cases occur in the United States. Women comprise 147,000 of the new cases globally and 10,000 of the new cases in the United States. Incidence estimates for 2012 are slightly increased to 11,710 newly affected women. Based on data from the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) database (2005–2009), the median age at diagnosis is 62 years. About 6% of the patients are between 35 and 44 years, and the incidence rate increases with increasing age. Worldwide the incidence rates vary, based on the regional prevalence of risk factors such as use of tobacco, alcohol, and/or betel quid. The rates among women are lower when compared with men; however, recent trends show an increase in the incidence among women. In 1950, the male to female ratio was 6:1 but by the year 2002 the gap had closed to a ratio of 2:1.

For the newly diagnosed patient with OPC, the effect is detrimental to both quality of life and survival ( Table 1 ). More than 79,000 women die every year globally as a result of OPC, with approximately 2400 annual female deaths in the United States. Based on mortality statistics from 2005 to 2009, the age-adjusted death rate was 2.5 per 100,000 men and women per year. The average 5-year survival rate of 50% has not changed significantly in the last 3 decades. Surviving the disease depends, among other factors, on the clinical stage at diagnosis. Based on SEER data from 2002 to 2008, the average 5-year survival exceeds 85% if diagnosed early, drops to 57% if the cancer presents with regional stage (spread to regional lymph nodes), and further decreases to 35% when the cancer has metastasized (distant stage).

| Cancer | Incidence | Mortality | 5-Year Prevalence | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | (%) | ASR (W) | N | (%) | ASR (W) | N | (%) | Proportion | |

| Women | |||||||||

| World | |||||||||

| Lip, oral cavity | 92524 | 1.5 | 2.5 | 44545 | 1.3 | 1.2 | 209581 | 1.4 | 8.5 |

| Nasopharynx | 26589 | 0.4 | 0.8 | 15625 | 0.5 | 0.4 | 68975 | 0.5 | 2.8 |

| Other pharynx | 28034 | 0.5 | 0.8 | 19092 | 0.6 | 0.5 | 59008 | 0.4 | 2.4 |

| United States | |||||||||

| Lip, oral cavity | 7355 | 1.1 | 2.8 | 1411 | 0.5 | 0.4 | 23372 | 1.1 | 18.4 |

| Nasopharynx | 565 | 0.1 | 0.3 | 186 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 1640 | 0.1 | 1.3 |

| Other pharynx | 2077 | 0.3 | 0.8 | 784 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 5173 | 0.3 | 4.1 |

| Men | |||||||||

| World | |||||||||

| Lip, oral cavity | 170496 | 2.6 | 5.2 | 83109 | 2.0 | 2.6 | 401075 | 3.0 | 16.3 |

| Nasopharynx | 57852 | 0.9 | 1.7 | 35984 | 0.9 | 1.1 | 153736 | 1.1 | 6.3 |

| Other pharynx | 108588 | 1.6 | 3.4 | 76458 | 1.8 | 2.4 | 229030 | 1.7 | 9.3 |

| United States | |||||||||

| Lip, oral cavity | 15817 | 2.1 | 7.3 | 2435 | 0.8 | 1.1 | 52326 | 2.4 | 43.2 |

| Nasopharynx | 1352 | 0.2 | 0.7 | 415 | 0.1 | 0.2 | 4094 | 0.2 | 3.4 |

| Other pharynx | 8144 | 1.1 | 3.9 | 2359 | 0.8 | 1.1 | 21536 | 1.0 | 17.8 |

Contrast between cervical cancer and oral cancer

Cervical and oropharyngeal cancers in the United States share some risk factors and etiologic factors. The potential to decrease the incidence of cervical cancer in the United States through vaccination against human papilloma virus (HPV) has been the subject of much attention and debate in the popular and scientific press. Taking the concept further to OPC and head and neck cancers has stimulated further discussion.

Consequently, the authors reasoned that a contrast of incidence of cervical cancer and OPC in women in the United States would help illuminate progress to date on improving the incidence rates of squamous cell carcinomas at these 2 sites. The SEER Program (1992–2009) 13 registry research data were analyzed using SEER*Stat software version 7.1.0. Data, restricted to females, included total oral cavity and pharynx (OCP) (lip, tongue, salivary gland, floor of mouth, gum and other mouth, nasopharynx, tonsil, oropharynx, hypopharynx, and other OCP) and cervix uteri; both with histology type ICD-O-3=8050-8084. Parameters included annual age-adjusted incidence rates per 100,000 standardized to the 2000 United States standard population ( www.seer.cancer.gov ).

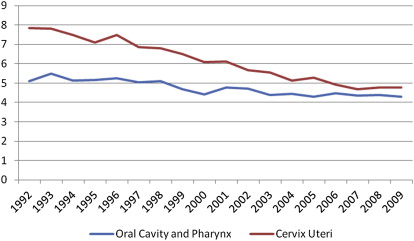

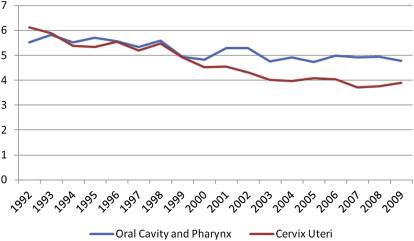

Fig. 1 contrasts OPC and cervical cancers for all women. Cervical cancer decreases from nearly 8 per 100,000 women in 1992 to just below 5 per 100,000 in 2009. A less dramatic decrease is seen for OPC, from just over 5 per 100,000 in 1992 to above 4 per 100,000 in 2009. The incidence rates for the 2 cancers appear to be closing in on each other. More startling is the contrast conveyed in Fig. 2 . Among non-Hispanic white women, the incidence rate of OPC has been higher than that for cervical cancer for almost every year since 1994, and rather distinctively so starting around 2000.

Choosing to contrast these 2 sets of cancers can be argued against, as the linkages to HPV may be incongruent and there are inherent limitations of secondary data analysis. However, the comparisons help illustrate that oral cancer is a woman’s cancer. Continued surveillance of HPV-associated cancers is warranted. Studies monitoring the impact of HPV vaccines suggest that within the short time since the introduction of quadrivalent HPV there is “evidence of a substantial decrease in vaccine-type HPV prevalence in the community, as well as evidence of herd protection.” The potential impact on OPC cancers should be included in future monitoring of the impact of HPV vaccine. In addition, traditional risk-factor monitoring and interventions should be retained.

Analytical epidemiology: risk factors

The 2 predominant risk factors for OPC in the United States population are alcohol and tobacco consumption. More than 75% of the variation in the incidence can be explained by excessive tobacco and alcohol use; individuals exposed to the combination of high levels of both substances experience the greatest risk. Other risk categories include diet, genetic predisposition, having a potentially malignant lesion such as erythroplakia, and the effect of carcinogenic HPV types, especially HPV-16 and HPV-18.

Alcohol and oral cancer

Excessive alcohol consumption has been consistently associated with risk of cancer, particularly cancers of the liver, digestive tract, and oral cavity. In the United States, men who consume more than 2 drinks per day and women who consume more than 1 drink per day seem to experience a higher incidence of oral cancer. However, most studies of the epidemiology of oral cancer involve men, especially smokers. Among nonsmokers, OPCs are relatively rare, and few published studies have included enough cases to provide meaningful information about the effect of alcohol, especially among women. Although some evidence indicates that women may be more susceptible than men to alcohol-induced carcinogenesis, the magnitude of alcohol’s effect on the risk of oral cancer in women remains understudied.

The World Health Organization (WHO) Global Status Report places the relative risks for oral cancer among females at 1.45 for those consuming 0 to 19.99 g/d of alcohol, 1.85 for those consuming 20 to 39.99 g/d, and 5.39 for those consuming more than 40 g/d. Although it is helpful to have such summary estimates, a qualitative assessment of the published literature indicates that studies on the alcohol-oral cancer risk association are mostly case-control studies that involve men, predominantly smokers. In men, prospective studies agree with case-control studies in that high levels of alcohol intake lead to higher cancer risk. However, among women the role and extent of alcohol as a risk factor for oral cancer has been inconsistent ; studies have been mostly case-control in design and have very few female participants.

Few studies have been conducted that indicate a change in the male to female ratio in higher risk for oral cancer in women. Among 67 nonsmoking and nondrinking patients (22 males and 45 females) with newly diagnosed, previously untreated oral squamous cell carcinoma (OSCC), 15 developed recurrence, 10 metastasis, and 3 both conditions during a median follow-up of 16.7 months. In this study it is notable that the number of women is twice that of men. Among previously undiagnosed nonsmoking, nondrinking patients with oral cancer, 28 were mostly female (75% vs 30%, P <.001), young (median 31.5 years vs 35.5 years, P = .007) and white (89% vs 60%, P = .006). A descriptive study of 172 nonsmoking, nondrinking patients reported that 45% were women, with more than half the patients being positive to HPV-16.

In a recent prospective study of women in France the majority of the nonsmokers (93%) were nondrinkers, and among those who consumed alcohol the level of intake was very high (>100 g/d). A large multicenter pooled case-control study of 15 studies from North America, Europe, and South America showed that overall, for men and women, the odds ratio (OR) for 3 or more drinks per day versus no drinking was 2.04 (95% confidence interval [CI] = 1.29–3.21) with a weak effect of alcohol among never smokers. A case-control study in Italy found that the risk increased among nonsmoking females only for those consuming 35 or more drinks per week. In the authors’ study using the Nurses Health Study (NHS) I data, a prospective analysis of about 88,800 women with 26 years of follow-up found that high alcohol intake (≥30 g/d or approximately 2 drinks/d) was significantly associated with an increased risk of oral cancer after adjusting for age, tobacco use, folate intake, and follow-up time. This analysis also showed a significant interaction between alcohol consumption and folate intake; alcohol appears to increase risk significantly only for those with low folate intake (<350 μg/d).

Low or moderate alcohol intake does not appear to increase the risk of oral cancer, even being associated with decreased risk. The literature on the role of low or moderate consumption on the risk of developing oral cancer or on a possible threshold effect is inconsistent. Some case-control studies have observed a U-shaped relationship between the risk of oral cancer and alcohol consumption. More specifically, a U-shaped relationship has been reported in 6 of 16 case-control studies; according to these studies, drinking small amounts of alcohol seems to be protective but drinking high amounts seems to be detrimental. In other studies, the existence of a U-shaped curve could not be assessed because of the low cutoff point of using fewer than 4 drinks per day. However, the U-shaped curve has been observed mostly in men, possibly because of the low samples of women in the highest consumption strata. It is currently unclear as to why alcohol at lower levels may be protective against oral cancer. It is plausible that low levels of alcohol in postmenopausal women are correlated with increased insulin sensitivity and elevated estrogen levels. Recently, an analysis of 74,372 women participants of the National Institutes of Health–American Association of Retired Persons cohort showed a protective effect of menopausal hormone therapy (MHT). Women who had especially received estrogen-progestin MHT had a 0.47-fold risk of developing squamous cell carcinoma of the upper aerodigestive tract (protective association). However, this is a preliminary report that requires further study.

Multiple mechanisms are involved in alcohol-induced carcinogenesis, and several studies have been conducted in both humans and animals. Locally in the oral cavity the ethanol in alcohol produces epithelial atrophy, which increases the penetration of carcinogens through the oral mucosa. This process may occur because of either the elimination of the lipid component of the barrier present in the epithelial layer or reorganization of the cell membrane by ethanol, which increases permeability. Ethanol by itself has not been proved to be carcinogenic ; however, acetaldehyde, the primary metabolic product of ethanol, has been established as carcinogenic in animal experiments and possibly carcinogenic in humans as well. Acetaldehyde causes DNA mutations, and interferes with DNA synthesis and repair. Acetaldehyde can also be produced by oral bacteria, adding to the total circulating salivary acetaldehyde. Regarding the genetics of alcohol metabolism, the production of acetaldehyde from ethanol is facilitated by alcohol dehydrogenase (ADH). Acetaldehyde is further converted to acetate by aldehyde dehydrogenase (ALDH). It is interesting that genetic polymorphisms of both ADH and ALDH are associated with an increased risk of head and neck cancers.

As regards gender differences, it is currently unclear if there are differences in the effect of alcohol intake on oral cancer. Most studies have involved men, with women being grossly underrepresented among study participants. It is possible that there may be differences in susceptibility to alcohol-induced carcinogenesis, with women being more susceptible, although the evidence is inconclusive. It is also possible that a gender effect may exist in alcohol gastric metabolism, which in turn may affect the bioavailability of acetaldehyde in the oral epithelial tissue. In men, the blood level of alcohol is higher when given intravenously than when drinking it. However, women have been found to have similar blood levels of alcohol irrespective of whether the alcohol was given orally or intravenously. This finding could be due to the lower gastric metabolism of ethanol in comparison with men. Studies on cancer of the liver have shown that liver damage is higher in females than in males at lower intake of alcohol and shorter duration of intake. Hormonal differences in men and women can also play a role in the joint effect of folate and alcohol and how they influence differences in the risk of oral cancer.

As the epidemiology of oral cancer in women remains understudied, more studies are urgently needed to explore and validate biological pathways involving alcohol consumption and the risk of oral cancer among women.

Tobacco and oral cancer

Smoking and tobacco use pose a serious risk of death and disease for women. Annually, cigarette smoking kills an estimated 173,940 women in the United States. Worldwide, it is estimated that men smoke nearly 5 times as much as women, but the ratios of female to male smoking prevalence rates vary dramatically across countries. In high-income countries such as Australia, Canada, the United States, and most countries of western Europe, women smoke at nearly the same rate as men. However, in many low-income and middle-income countries women smoke much less than men. For example, in China 61% of men are reported to be current smokers, compared with only 4.2% of women. Similarly, in Argentina 34% of men are reported to be current smokers compared with 23% of women. The most common form of tobacco use is smoking of manufactured cigarettes, although in some areas of the world (eg, Asia), other forms of tobacco ingestion are used such as the smoking of traditional hand-rolled flavored cigarettes referred to as beedis, use of water pipes to smoke tobacco, use of snuff, smokeless tobacco, and reverse cigarette smoking.

Prevalence of Smoking Among Women in the United States

Results from survey by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) in 2010 showed that more than 1 in 6 American women aged 18 years or older (17.3%) smoked cigarettes. The highest rates were seen among American Indian/Alaska Native women (36%) followed by multiracial women (23.8%), white (19.6%), African American (17.1%), Hispanic (9%), and Asian women (4.3%). In general, the less education a woman has, the more likely it is she will smoke. For instance, women with less than a high school education are more than twice as likely as college graduates to smoke.

In 2008, approximately 15% of young women aged 20 to 24 years smoked during pregnancy. Even among younger teenagers 15 to 19 years old, 13.1% smoked during pregnancy. The lowest rates were seen in mothers younger than 15 years (3.2%), between 40 and 54 years (4.6%), 35 to 39 years (4.9%), and 30 to 34 years of age (5.6%).

Risks Associated with Tobacco Use Among Women

Intensity, duration, and age at smoking

Data suggest that women may be more sensitive than men to some of the harmful effects of smoking, with evidence that risk increases with the number of cigarettes smoked.

Dose response is measured in terms of intensity of smoking (cigarettes/d), duration of smoking, or pack-years. A positive significant trend was found among women who smoked cigarettes and used tobacco. Macfarlane and colleagues showed that women who had 1 to 18 cigarette pack-years had a relative risk of 2.6, whereas men who had 1 to 33 cigarette pack-years had a relative risk of 1.1. Women who smoked more than 18 pack-years had a risk of 4.6, whereas men who smoked more than 33 pack-years had a risk of only 1.3. With an increase in the number of cigarettes smoked daily or an increase in daily tobacco consumption there was an increase in risk, and the trend was statistically significant. According to Hayes and colleagues, the risk of developing oral cancer was higher in women than in men. Women who smoked 1 to 9 cigarettes/d had a risk of 2.2 compared with a risk of 0.9 in men. Women who smoked more than 40 cigarettes/d had a risk of 28.1, compared with a risk of only 4.9 in their male counterparts. The P trend for daily cigarette intake was .0001 for women. Hammond and Seidman concluded that women who were regular smokers had a risk of 3.3 of developing cancer of the upper aerodigestive tract. As the use of tobacco in terms of g/d increased, it was associated with higher risk of oral cancer. For women who use about 1 to 7 g of tobacco per day the risk was 5.6, and when tobacco use increased to more than 8 g/d the risk was 5.9. According to Blot and colleagues, younger women had a higher risk of developing cancers of the aerodigestive tract. Women in the age group 17 to 24 had a risk of 3.1 and those younger than 17 had a risk of 2.9, whereas women who were 25 years and older had a risk of 2.8.

The OR increased with an increase in pack-years for women. ORs for smoking and drinking were greater in women with respect to oropharyngeal and hypopharyngeal cancers, but were similar for both men and women for oral-cavity and laryngeal cancers. For 30 to 39 pack-years, for cancer of the oral cavity the OR is 3.18, for oropharyngeal cancer the OR is 1.34, for hypopharyngeal cancer the OR is 6.62, and for laryngeal cancer the OR is 2.22.

Cessation of smoking

Relative risks for former smokers were always lower than those for current smokers. Hayes and colleagues showed that women who were current smokers had a risk of 4.9 compared with 3.9 for men. When risks among women were examined by years since quitting, a negative trend was seen. Women who had quit smoking for less than 2 years had a risk of 14.1 compared with women who had a risk of 8.7 who had quit smoking for about 2 to 9 years, a risk of 2.1 for those who had quit smoking for about 10 to 19 years, and a risk of only 0.8 for those who had quit smoking for more than 20 years.

Type of tobacco

In the study by Hayes and colleagues, women who use only other forms of tobacco had a higher risk for oral cancer in comparison with women who used cigarettes and other forms of tobacco. Consumption of black tobacco and filter-tipped cigarettes led to a higher risk of oral cancer than did consumption of blond tobacco and cigarettes without a filter. Women who used black tobacco had a risk of 6.9, compared with a risk of 6 among women who used blond tobacco. Among women who used filter-tipped cigarettes, the risk was 6.3 compared with a risk of 5.2 among women who used cigarettes without a filter. For more details on the effects of tobacco on cancer risk, and especially for aerodigestive cancers, the reader is encouraged to consult the International Agency of Research on Cancer (IARC) Monograph 83, which contains many of the studies referenced in this article.

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses