In this article, we report successful orthodontic treatment combined with segmental distraction osteogenesis after a modified LeFort II osteotomy in a patient with craniosynostosis. An 8-year-old boy diagnosed with craniosynostosis had a dished-in face, an anterior crossbite, and a skeletal Class III jaw relationship because of midfacial hypoplasia. At the age of 13 years 6 months, the maxillary second and mandibular first premolars were extracted, and leveling and alignment of both arches was started with preadjusted edgewise appliances. At age 14 years 11 months, the patient had a modified LeFort II osteotomy, and the maxillary segment was advanced 7 mm and fixed to the zygomatic bone. At the same time, segmental distraction osteogenesis was started with a rigid external distraction system, and the nasal segment was advanced for 20 days at a rate of 1.0 mm per day. The total active treatment period was 40 months. As a result of the modified segmental distraction osteogenesis, significant improvement of his severe midfacial hypoplasia was achieved without excessive advancement of the maxillary dentition. Both the facial profile and the occlusion were stable after 1 year of retention. However, the nasal segment relapsed 1.4 mm during the 1.5 years after the segmental distraction osteogenesis. Evaluation of the stability and retention suggests that some overcorrection in midfacial advancement is recommended.

Craniosynostosis is a congenital malformation characterized by the premature synostosis of the cranial sutures and midfacial hypoplasia causing hypertelorism and exophthalmos. Because of the midfacial hypoplasia, these patients often demonstrate a skeletal Class III jaw relationship with an anterior crossbite and require orthodontic or orthopedic treatment for both functional and esthetic reasons. To treat the midfacial hypoplasia, distraction osteogenesis has been commonly used in the past decade because it could provide significant midfacial advancement with gradual progress compared with traditional orthognathic surgeries. Distraction osteogeneis with a LeFort III osteotomy has been preferentially applied in patients with severe hypoplasia and exophthalmos to improve their facial esthetics.

On the other hand, the severity of the malocclusion differs greatly in patients with craniosynostosis. Some patients with severe midfacial dysplasia even show a mild Class III occlusion. The discrepancy between the facial profile and the occlusion often causes difficulties in treatment planning. A single osteotomy is occasionally unsuitable for improving the complicated skeletal problems. Polley and Figueroa demonstrated the usefulness of piggyback osteogenesis to move the upper and lower midfacial segments. Additionally, several reports have shown acceptable results of dual segmental distraction osteogenesis after LeFort I and III osteotomies in patients with midfacial hypoplasia. However, there are few reports of combining LeFort I and II osteotomies for segmental distraction osteogenesis in patients with craniosynostosis.

This article demonstrates a good prognosis for a patient with craniosynostosis treated with a modified LeFort II segmental distraction osteogenesis by using a rigid external distraction osteogenesis system.

Diagnosis and etiology

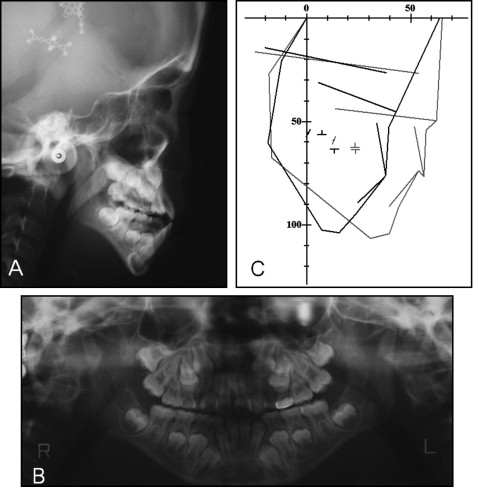

An 8-year-old boy came to the outpatient clinic of Tokushima University hospital in Japan. His chief complaint was an anterior crossbite. He had been diagnosed with a craniosynostosis subtype at birth in the Hyogo Prefecture Children’s Hospital and had an operation for hydrocephalus. Furthermore, he had a medical history of anal atresia, otitis media, cryptorchism testis, hypoplasia of the elbow, and an auditory disturbance. A dished-in face, mild exorbitism, and a short upper lip due to midfacial hypoplasia were noted ( Fig 1 ). He had mild obstructive sleep apnea syndrome in a dorsal position. An anterior crossbite with an overjet of −0.2 mm and an overbite of −1.6 mm were observed. The terminal plane was a mesial step type on both sides. Severe crowding was expected because of the lack of eruption spaces for the permanent teeth ( Fig 2 ). Cephalometric analysis, when compared with the Japanese norm, showed a skeletal Class III jaw-base relationship (ANB, −2.0°) because of a severe maxillary deficiency (SNA, 64.9°). In the mandible, the ramus height was within the normal range, but the body length was significantly short. In the panoramic radiograph, a mediodens was observed ( Fig 2 ).

Treatment objectives

The patient was diagnosed as having a Class III malocclusion, with a skeletal Class III jaw relationship caused by midfacial hypoplasia. The treatment objectives were to (1) correct the midfacial hypoplasia and the dished-in face, (2) correct the anterior crossbite and establish ideal overjet and overbite, and (3) achieve an acceptable occlusion with a good functional Class I occlusion.

We planned a segmental distraction osteogenesis with a modified LeFort II osteotomy to improve both the facial profile and the skeletal jaw relationship. The midfacial advancement was performed on 2 levels: the upper segment including the anterior nasal spine and the lower segment consisting of the maxillary dentition.

Treatment alternatives

Several procedures were explored to achieve a proper facial profile and an acceptable occlusion. A conservative treatment of maxillary growth modification by using a maxillary protraction headgear during the growing phase was considered to be effective to modify his skeletal Class III jaw relationship; however, this procedure might not have corrected his severe skeletal disharmony and obstructive sleep apnea syndrome completely, and it seemed to be a compromised treatment. Multi-bracket treatment with tooth extraction after his growth spurt could be useful for correcting his Class III malocclusion with a negative overjet, but it would not improve his concave profile caused by the midfacial deficiency. Therefore, we chose an orthodontic-surgical treatment for this patient.

In growing patients with craniosynostosis, traditional surgical-orthodontic treatments provide good prognoses, but we planned the distraction osteogenesis after his growth spurt for the following reasons: (1) the anterior crossbite was not observed when the first molars erupted, (2) some premolars needed to be extracted to improve the severe crowding, and (3) the distance and direction of the required advancement of the distraction osteogenesis were more predictable in adolescence than in childhood.

Treatment progress

After the extraction of the mediodens, we followed the patient until the end of his active growth ( Figs 3-5 ). At the age of 13 years 6 months, his maxillary second premolars and mandibular first premolars were extracted to gain eruption space for the canines. An 0.018-in slot preadjusted edgewise appliance was placed in both arches, and leveling and alignment with nickel-titanium archwires were started. He showed a skeletal Class III jaw relationship with an ANB angle of −4.1° at that time.

After 1 year of preoperative orthodontic treatment, segmental distraction osteogenesis was performed at the Department of Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery, Yokohama City University Graduate School of Medicine. After the modified LeFort I and II osteotomies, the maxillary segment was advanced approximately 7 mm, including overcorrection, and fixed to the zygomatic bone. Then a rigid external distraction system was placed on the cranial bone at the same time ( Fig 6 ). The segmental distraction osteogenesis was started 6 days after surgery and continued for 20 days at a rate of 1.0 mm per day. After the osteogenesis, the rigid external distraction device was removed, and Kirschner wires were inserted between the nasal segment and the zygomatic bone for retention.

At the age of 16 years 10 months, the edgewise appliances were removed, and circumferential retainers and lingual bonded retainers were placed in both arches. The total active treatment period was 40 months.

Treatment results

After the segmental distraction osteogenesis, the midfacial hypoplasia and the facial profile were dramatically improved ( Fig 7 ). Cephalometric evaluation after the segmental distraction osteogenesis showed nasal advancement of 16.2 mm at rhinion and maxillary advancement of 5.9 mm at Point A to the reference line, which was defined as a perpendicular line to the sella-nasion plane through sella ( Fig 8 ). A skeletal Class I jaw relationship was also achieved (ANB, 3.2°). Because the maxilla was moved in a forward and downward direction, the mandibular plane angle was increased by 1.2°. The negative overjet was overcorrected to 5.1 mm, and the anterior open bite was improved (overbite, 2.0 mm; Table ).