The face is generally the first to reveal signs of aging. Rejuvenating the aging face has gained tremendous popularity over the last 2 decades. In the past, incisional face-lifting was the main strategy for facial rejuvenation, but during the past decade cosmetic surgeons have revolutionized facial rejuvenation with adjunctive procedures such as alloplastic facial implants, chemodenervation, injectable fillers, and skin resurfacing via laser or chemical exfoliation. Although we now have several weapons to reverse the signs of facial aging, the “modern” face-lift is still the “gold standard” for correcting generalized facial cutis laxa (rhytidosis), jowling, cervicomental redundant skin, and platysmal banding. Facial dyschromia, changes in pigmentation, acne scarring, and deep wrinkles can all be treated with the adjunctive procedures described later in this chapter and in other dedicated chapters in this textbook.

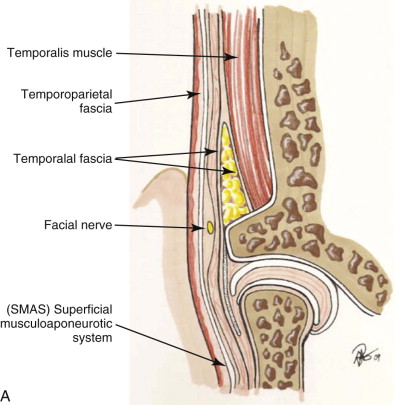

The face-lifts described in the early literature involved skin excision only. Even though the benefit is usually temporary and a rather poor natural appearance results, some surgeons still use this technique for certain patients with unique anatomy or for revision surgery. The current face-lifting techniques are numerous, although most involve manipulation of the superficial musculoaponeurotic system (SMAS). SMAS involvement in face-lifting was first introduced by Mitz and Peyronie in 1976 when their landmark article was published.

Historical details regarding face-lifting are evident from publications in the literature, such as those by Hollander (1912), Lexter (1931), Joseph (1921), Passant (1919), Bourget (1921), and Madam Noel (1926). At that time surgeons and patients were reluctant to make their cosmetic surgical interest public. Hence, technical advances were slow to flourish and propagate ( Box 107-1 ). Even with extensive undermining of skin flaps during face-lifts decades ago, the results were only partially beneficial and did not emphasize pathology of the neck and the platysma. A better understanding of facial anatomy was described by Skoog in 1974, and his manipulation of facial tissue led to the future advancements in face-lifting surgery. Webster and colleagues later added that extensive subcutaneous dissection leads to greater exposure of raw surfaces with an increased risk for complications. Richard Webster was one of the first to recommend a “short flap” with basic SMAS plication and suggested that the skin would advance adequately from its attachment to the elevated deep tissue.

- •

Subcutaneous rhytidectomy (Lexar, 1916)

- •

Subcutaneous and platysma (Skoog, 1974)

- •

Subcutaneous with description of the superficial musculoaponeurotic system (Mitz and Peyronie, 1976)

- •

Musculofascial plane described (Jost and Levet, 1984)

- •

Subperiosteal technique (Tessier, 1990; Psilakis, 1988; Ramirez, 1991)

- •

Deep-plane technique (Hamra, 1984)

- •

Composite technique (Hamra, 1990)

- •

Mini-lifts, e.g., S-lift (Saylan and others, 2003)

- •

“Lifestyle or Quick Lift”: just patented “mini”-lifts

- •

“MACS lift,” minimal-access cranial suspension (Tonnard and Verpaele, 2004)

Etiopathogenesis

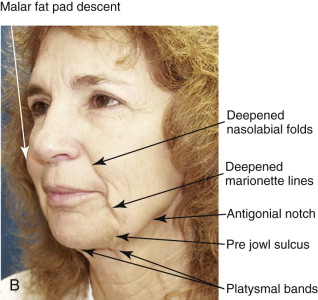

Indications for face-lifting cosmetic surgery are numerous and involve the changes that accompany facial aging. First, the patient is identified as seeking facial rejuvenation because of age-related complaints. Upper face-lifting is described in a separate chapter, and our focus here is to target the lower part of the face and neck. Cutis laxa of the jowls and cervical area, deepened nasolabial fissures, and platysmal banding are the main complaints that are targeted by current face-lifting strategies. Genetics, age, and smoking are the key determinants of the cause of signs of facial aging ( Fig. 107-1 ). In general, the average age when patients first seek lower face-lifting and neck lifting can vary widely from 45 to 65 years.

Clinical Anatomy

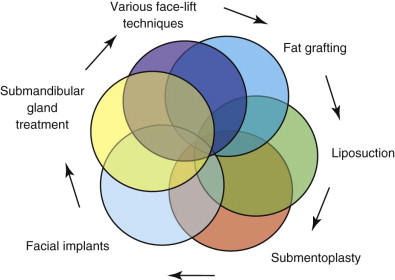

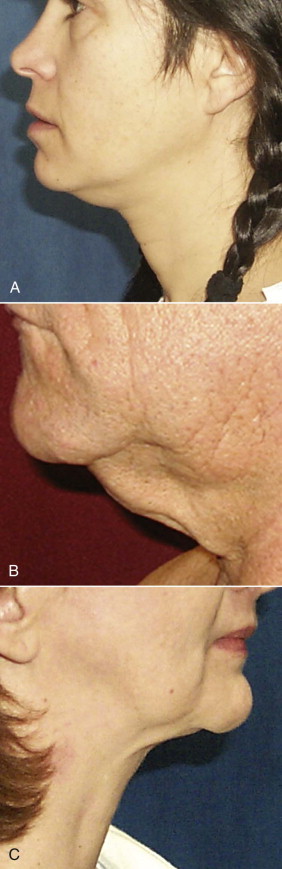

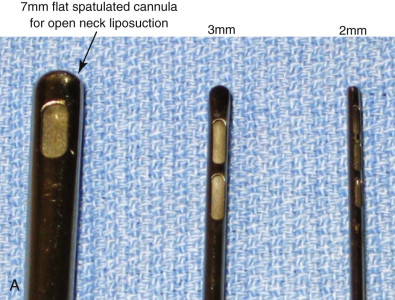

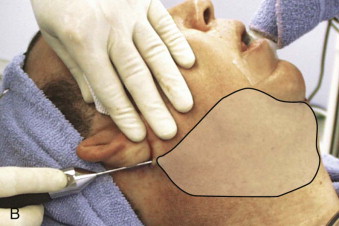

Surgeons have multiple techniques at their disposal to perform face-lifts, although detailed knowledge of surgical facial anatomy is the key to any cosmetic surgery, regardless of the techniques used ( Figs. 107-2 and 107-3 ). Determining who is best suited for liposuction versus submentoplasty with or without a face-lift is at least half the battle for ultimately producing pleasing esthetic results ( Figs. 107-4 to 107-6 ). Basic neck liposuction for an ideal patient can be dramatic despite being a relatively simple procedure when performed well ( Fig. 107-7 ).

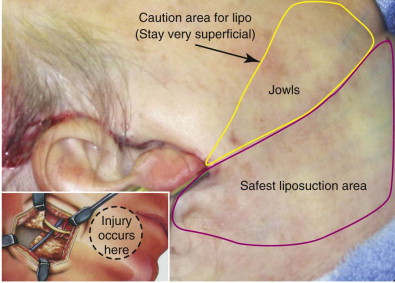

Detailed knowledge of the anatomy in conjunction with the pathology to be corrected is necessary for correct surgical planning and preoperative markings ( Fig. 107-8 ). Marking the skin over the known danger zones can reduce the risk for complications and neurovascular injury ( Fig. 107-9 ). These areas are often obscured when the patient is in the supine position and distorted with local anesthetic.

A surgeon must be mindful of three main danger zones: the mid-zygomatic temporal region, the malar eminence region, and the area at the inferior border of the mandible near the angle. The mid-zygomatic arch area contains the temporal or frontal branch of the facial nerve ( Fig. 107-10 ). The nerve crosses over the arch approximately 2 cm from the external auditory meatus. It can be easily injured in the area over the bony prominence where there is less soft tissue.

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses