This article presents current concepts of managing teeth with traumatic pulp exposures. The article includes a description of the traumatology of crown fractures, discussion of treatment considerations, a summary of materials for vital pulp therapy, and an outline of techniques for treating pulp exposures.

Vital pulp therapy has a long history in dentistry. Its purpose is to maintain vitality of the pulp, a goal that is particularly desirable in the case of young, immature teeth ( Fig. 1 ). The use of vital pulp therapy is, however, not necessarily confined to developing teeth; any tooth, regardless of stage of development and maturity, can be preserved after traumatic or accidental exposure if the pulp is healthy. It is now also recognized that many teeth with carious pulp exposure can have vital pulp therapy with predictable outcomes. Success depends on a good understanding of pulp biology, the use of appropriate materials, and sound technical procedures.

This article presents current concepts of managing teeth with traumatic pulp exposures. The article includes a description of the traumatology of crown fractures, discussion of treatment considerations, a summary of materials for vital pulp therapy, and an outline of techniques for treating pulp exposures.

Traumatology of crown fractures

Crown fractures are common traumatic injuries to teeth and are categorized as enamel fractures, uncomplicated fractures (enamel-dentin fractures), complicated fractures (involving enamel, dentin, and exposure of the pulp), and crown-root fractures, which may be uncomplicated (no pulpal involvement) or complicated (with pulpal involvement).

A crown fracture that involves dentin exposes the pulp whether one can see and touch the soft pulp tissue or not. This is because a fracture involving dentin exposes dentinal tubules in direct communication with the pulp. Therefore, in crown fractures without direct pulp exposure in the teeth of young patients, it is prudent to protect the exposed dentin to prevent bacterial toxins, which are generated from the biofilm that quickly covers the surface of a fractured tooth, from penetrating through the exposed dentinal tubules into the pulp. The closer the fracture is to the pulp and the younger the patient, the larger is the diameter of the dentinal tubules.

A complicating factor associated with crown fractures is that the trauma may concomitantly have caused a luxation injury to the tooth, compromising the ability of the pulp to defend itself and recover from the injury. Luxation injuries damage the supporting structures, such as the periodontal ligament and the neurovascular bundle supplying the pulp through the apical foramen. If bacteria gain access to the pulp, either directly through a traumatic exposure or through open dentinal tubules, and the pulp is compromised because of reduced or cut-off blood supply, the pulp will likely become necrotic.

Treatment considerations

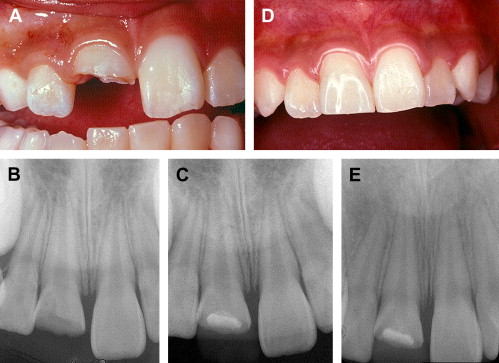

Treatment of an uncomplicated crown fracture can today be accomplished quite successfully by either a build-up with acid-etched composite resin or by reattaching the broken segment, if available, using a bonding system ( Fig. 2 ). The expected outcome for either approach is excellent: nearly 100% pulp survival regardless of root developmental status. Timely protection of exposed dentin in young, developing teeth is advisable to prevent the pulp from undergoing infection-related necrosis.

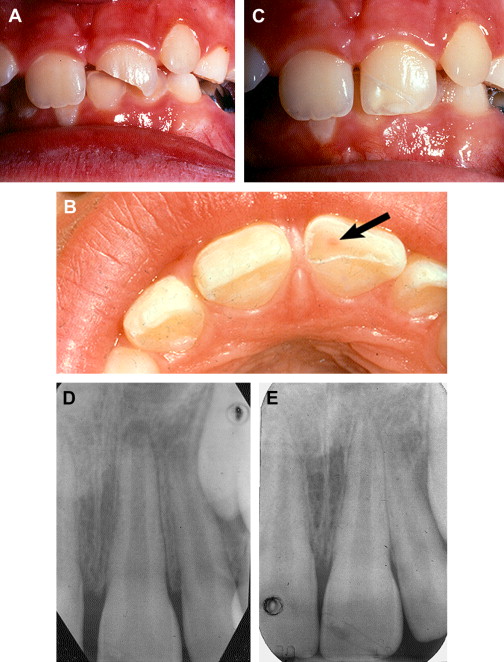

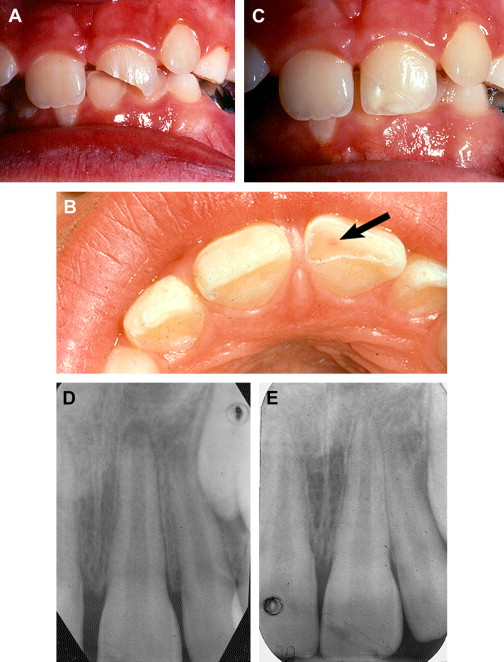

Complicated crown fractures in which direct pulp exposure occurs should not be viewed as hopeless situations for pulp survival ( Fig. 3 ). Correctly managed, many teeth can be treated using relatively simple procedures to allow continued pulpal function, an important consideration in young, immature teeth. Before any treatment approach is chosen, however, a number of questions should be asked.

First: How Long Ago was the Accident?

A common notion among many dentists is that if a pulp has been exposed for more than 24 to 48 hours, it has a poor chance of surviving. This is an unfortunate misconception that has led to unnecessary pulp removal of vital, productive pulp that could have been preserved. Like tissue from other kinds of wounds, exposed pulp soon develops granulation tissue to protect the exposed wound surface. True enough, bacteria will invade the pulp tissue gradually, but it can take many days for bacteria to penetrate even a few millimeters. Cvek demonstrated that the pulpotomy technique known by his name could successfully be done even several days after pulp exposure. A good rule is to proceed as soon as possible, but as long as the pulp is alive it can be treated.

Second: What is the Stage of Tooth Development?

If the fracture occurs in an adult with a fully formed root, and the treatment plan includes a prosthetic crown, it is probably more practical to perform the endodontic treatment prior to restoring the tooth because it would be undesirable to later have to do root canal treatment through a prosthetic crown. If, however, the tooth can be restored either by placing a composite resin build-up or by reattaching the fractured segment, the tooth can receive the same vital pulp therapy as recommended when developing teeth in young patients are fractured, which will be described below.

With respect to patient age and stage of tooth development, it is very important to make every effort to preserve pulp vitality in young patients with still developing teeth. Continued pulp vitality facilitates continued root development. This is a concept often overlooked when dealing with crown fractures. Practitioners tend to look at the root apex and, if that looks closed or nearly so, the assumption is that the tooth is fully formed. The area of the root that should be examined closely on the radiograph is the cervical part of the root. Young developing teeth often lack root thickness and that needs to develop even if the apical opening appears closed. Continued root development can be expected if the exposed pulp is properly protected. Vital pulp therapy, to be described below, is the goal in the management of crown fractures with pulp exposure in young patients.

Third: How Much Tooth Structure Remains?

Extensive loss of coronal tooth structure complicates the management of crown fractures. In cases involving both the crowns and the roots of teeth in adults, it often is prudent to consider extraction and replacement with an implant or a bridge. However, in young patients still growing and developing, efforts to save the injured teeth should be made even if the treatment is complex. In some cases, even if eventual loss is likely, it is worth saving the teeth for as long as possible in order to maintain the ridge contour, particularly in the maxillary anterior region.

In addition to determining the extent of damage, one should ask if the broken crown fragment is available. Particularly in young patients, reattaching a fractured crown fragment can be a very satisfactory approach to restoration of the tooth (See Fig. 2 ). The current-generation bonding agents provide an excellent means of reattaching the fragments to the remaining tooth. Resistance to refracture, while not equal to normal teeth, is quite acceptable.

While reattachment of fractured tooth fragments has become very acceptable in children, it is not often done in adults. There is, however, no technical reason why this procedure cannot also be done in adults. It may be that esthetic considerations, however, will dictate restoration with a porcelain veneer or a prosthetic crown.

Fourth: How Large is the Pulp Exposure?

This is a question that has relatively little importance. If the pulp is to be preserved, the exposure needs only to be small enough to accommodate bridging with a restorative material. A healthy pulp, regardless of how much tissue is exposed, has a great ability to survive as long as it can be protected from bacteria.

Treatment considerations

Treatment of an uncomplicated crown fracture can today be accomplished quite successfully by either a build-up with acid-etched composite resin or by reattaching the broken segment, if available, using a bonding system ( Fig. 2 ). The expected outcome for either approach is excellent: nearly 100% pulp survival regardless of root developmental status. Timely protection of exposed dentin in young, developing teeth is advisable to prevent the pulp from undergoing infection-related necrosis.

Complicated crown fractures in which direct pulp exposure occurs should not be viewed as hopeless situations for pulp survival ( Fig. 3 ). Correctly managed, many teeth can be treated using relatively simple procedures to allow continued pulpal function, an important consideration in young, immature teeth. Before any treatment approach is chosen, however, a number of questions should be asked.

First: How Long Ago was the Accident?

A common notion among many dentists is that if a pulp has been exposed for more than 24 to 48 hours, it has a poor chance of surviving. This is an unfortunate misconception that has led to unnecessary pulp removal of vital, productive pulp that could have been preserved. Like tissue from other kinds of wounds, exposed pulp soon develops granulation tissue to protect the exposed wound surface. True enough, bacteria will invade the pulp tissue gradually, but it can take many days for bacteria to penetrate even a few millimeters. Cvek demonstrated that the pulpotomy technique known by his name could successfully be done even several days after pulp exposure. A good rule is to proceed as soon as possible, but as long as the pulp is alive it can be treated.

Second: What is the Stage of Tooth Development?

If the fracture occurs in an adult with a fully formed root, and the treatment plan includes a prosthetic crown, it is probably more practical to perform the endodontic treatment prior to restoring the tooth because it would be undesirable to later have to do root canal treatment through a prosthetic crown. If, however, the tooth can be restored either by placing a composite resin build-up or by reattaching the fractured segment, the tooth can receive the same vital pulp therapy as recommended when developing teeth in young patients are fractured, which will be described below.

With respect to patient age and stage of tooth development, it is very important to make every effort to preserve pulp vitality in young patients with still developing teeth. Continued pulp vitality facilitates continued root development. This is a concept often overlooked when dealing with crown fractures. Practitioners tend to look at the root apex and, if that looks closed or nearly so, the assumption is that the tooth is fully formed. The area of the root that should be examined closely on the radiograph is the cervical part of the root. Young developing teeth often lack root thickness and that needs to develop even if the apical opening appears closed. Continued root development can be expected if the exposed pulp is properly protected. Vital pulp therapy, to be described below, is the goal in the management of crown fractures with pulp exposure in young patients.

Third: How Much Tooth Structure Remains?

Extensive loss of coronal tooth structure complicates the management of crown fractures. In cases involving both the crowns and the roots of teeth in adults, it often is prudent to consider extraction and replacement with an implant or a bridge. However, in young patients still growing and developing, efforts to save the injured teeth should be made even if the treatment is complex. In some cases, even if eventual loss is likely, it is worth saving the teeth for as long as possible in order to maintain the ridge contour, particularly in the maxillary anterior region.

In addition to determining the extent of damage, one should ask if the broken crown fragment is available. Particularly in young patients, reattaching a fractured crown fragment can be a very satisfactory approach to restoration of the tooth (See Fig. 2 ). The current-generation bonding agents provide an excellent means of reattaching the fragments to the remaining tooth. Resistance to refracture, while not equal to normal teeth, is quite acceptable.

While reattachment of fractured tooth fragments has become very acceptable in children, it is not often done in adults. There is, however, no technical reason why this procedure cannot also be done in adults. It may be that esthetic considerations, however, will dictate restoration with a porcelain veneer or a prosthetic crown.

Fourth: How Large is the Pulp Exposure?

This is a question that has relatively little importance. If the pulp is to be preserved, the exposure needs only to be small enough to accommodate bridging with a restorative material. A healthy pulp, regardless of how much tissue is exposed, has a great ability to survive as long as it can be protected from bacteria.

Materials for vital pulp therapy

Many dental materials have been proposed for protecting exposed dental pulps: calcium hydroxide, hydrophilic resins, resin-modified glass ionomer, tricalcium phosphate, and mineral trioxide aggregate (MTA). Are some materials better than others? It is probably safe to say that a dental material per se has little direct effect on pulp tissue, particularly after the material has set into its permanent stage. The reason some materials do better than others when placed on exposed pulps relate to the ability of the individual material to prevent bacterial contamination of the pulp. This was clearly demonstrated by Cox and colleagues. The most important characteristic then of a dental material with respect to its value in vital pulp therapy is its ability to prevent microleakage.

The best known and most widely used vital pulp therapy material has for many years been calcium hydroxide. First used over 80 years ago in teeth with deep carious lesions, calcium hydroxide in time became recognized as a valuable pulp-capping and pulpotomy material. In modern times, perhaps no one has done more to promote the use of calcium hydroxide than Miomir Cvek, a pediatric dentist in Stockholm, Sweden, who was both a researcher and a clinician. His technique has been known as the Cvek pulpotomy technique and probably many thousands of teeth have been saved by the technique he promoted ( Fig 4 ).