This case report describes the successful treatment of severely impacted mandibular second molars with severe apical root resorption of the mandibular first molars. The vertically impacted second molars were orthodontically moved (using orthodontic mini-implants) without additional root resorption of the first molars. The orthodontic treatment provided a satisfactory and stable outcome by improving the periodontium surrounding the first and second molars. The treatment also eliminated the need for prosthetic treatment by preserving the first and second molars.

Highlights

- •

A patient had impacted mandibular second molars with apical first molar root resorption.

- •

Impacted second molars were moved with mini-implants without first molar root resorption.

- •

Orthodontic treatment provided a satisfactory and stable outcome.

- •

The periodontium around the first and second molars was improved.

- •

Preserving the first and second molars eliminated the need for prosthetic treatment.

Impaction of the mandibular second molar is relatively rare, with a prevalence of 0% to 2.3%. Second molar disturbances result from inadequate arch length, ectopic position of the follicle, an obstacle in the path of eruption, or failure of the eruption mechanism. A second molar impaction is categorized in terms of its angulation as mesial, vertical, or distal. Most impacted second molars are mesially inclined and can be corrected and brought into the occlusion by orthodontic uprighting.

Treatment of an impacted second molar is considered in the following sequence, starting with the most conservative option: orthodontic tooth movement, surgical repositioning, transplantation, and extraction of the impacted tooth. The orthodontic approach is the treatment of choice, with a success rate of 70%. This treatment is ideal for an impacted second molar during early adolescence when second molar root formation is still incomplete and before the complete development of the mandibular third molars. If left untreated, the impacted second molar can cause further problems such as root resorption, caries and periodontitis of the adjacent molars, cysts, malocclusion, pericoronal inflammation, and pain.

Several reports have presented the successful treatment of an impacted second molar by orthodontic uprighting or surgical repositioning. For complicated problems, the decision-making procedure is difficult because of uncertain etiology, lack of standard therapy, and few reported cases.

We report an adult with vertically impacted mandibular second molars accompanied by severe apical root resorption of the first molars. Our aims were to describe and discuss the treatment and the 3.5 years of successful retention in which the vertically impacted second molars were orthodontically moved into their appropriate positions without additional apical root resorption of the first molars.

Diagnosis and etiology

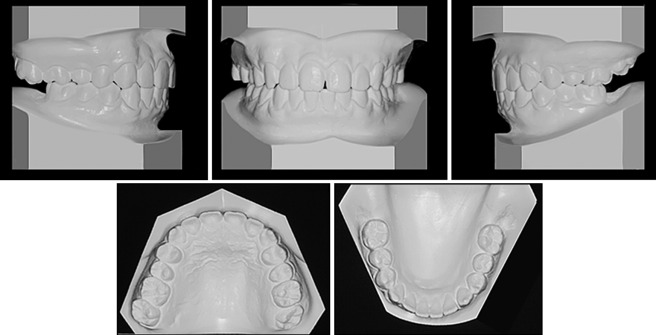

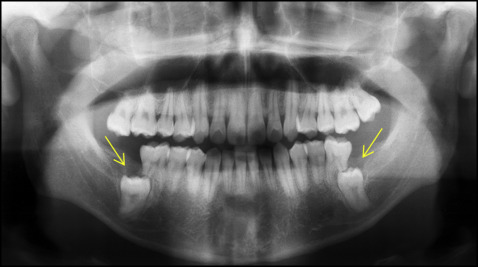

A 19-year-old man was referred from a private clinic because of impaction of the mandibular second molars ( Figs 1-4 ). The second molars were vertically impacted beneath the distal roots of the first molars, which were slightly extruded. The distal roots showed severe apical resorption, but they were not treated because their vitality and mobility were within normal limits with no specific symptoms. According to the patient, his mandibular third molars had been extracted approximately 8 months before because of horizontal impaction over the second molars. The maxillary right second molar was overextruded because of the impacted opposing tooth.

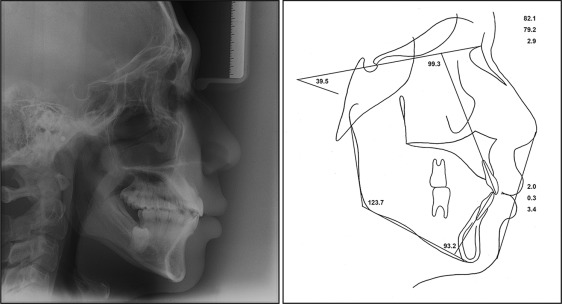

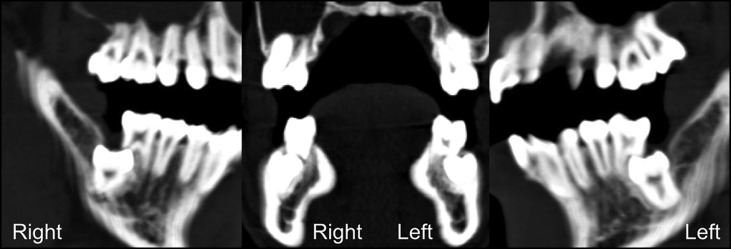

The patient had a good profile and mild facial asymmetry with deviation of the chin and the mandibular dental midline to the right side ( Fig 1 ). His dentition was well aligned with Class I molar and canine relationships ( Fig 2 ). The lateral cephalometric radiograph indicated a normal skeletal relationship with an ANB angle of 2.9° and a hyperdivergent facial profile ( Figs 3 and 4 ; Table ). The computed tomogram showed a buccoapical position of the second molars and severe apical resorption of the first molar distal roots ( Fig 5 ). The first molars had infrabony defects on the distal surfaces. On the basis of these findings, the patient was diagnosed as having a skeletal Class I malocclusion with vertical impaction of the mandibular second molars and severe apical root resorption of the mandibular first molars.

| Measurement | Initial | 23 months (locking resolved) | Posttreatment | Retention (3.5 years) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SNA (°) | 82.1 | 82.0 | 82.9 | 82.5 |

| SNB (°) | 79.2 | 75.8 | 78.6 | 78.4 |

| ANB (°) | 2.9 | 6.2 | 4.3 | 4.1 |

| Wits (mm) | 0.3 | 1.0 | −0.1 | −0.3 |

| Björk sum (°) | 399.4 | 403.3 | 401.1 | 401.3 |

| SN-MP (°) | 39.5 | 43.3 | 41.1 | 41.3 |

| Gonial angle (°) | 123.7 | 123.5 | 123.8 | 124.4 |

| Facial height ratio | 63.4 | 61.9 | 63.1 | 63.9 |

| U1-SN (°) | 99.3 | 101.2 | 98.0 | 98.4 |

| IMPA (°) | 93.2 | 94.7 | 90.0 | 90.5 |

| Upper lip to E-line (mm) | 2.0 | 5.1 | 0.8 | 0.6 |

| Lower lip to E-line (mm) | 3.4 | 4.9 | 2.0 | 1.8 |

Treatment alternatives

The decision of the most appropriate treatment plan for this patient was influenced by 2 major factors: (1) the difficulty of orthodontic traction or surgical extraction of the impacted second molars, and (2) the prognosis of each procedure. The treatment alternatives were (beginning with the most conservative option) preservation of the first and second molars, extraction of the first molars, extraction of the second molars, and extraction of the first and second molars.

The first option would preserve the first and second molars by moving the second molars backward. This option would be the least invasive and eliminate the need for additional prosthetic treatment. In addition, the alveolar bone levels of the first and second molars could be expected to improve. However, the long-term prognosis of severely resorbed roots is unclear, and the possibility of ankylosis of the second molars is uncertain. Furthermore, it would take a long time to bring the impacted second molars into occlusion.

The second option was to extract the first molars and substitute the first molars with the second molars. The extraction procedure of the first molars would not be as invasive as extraction of the second molars. The orthodontic treatment would be simpler, and the treatment duration would be shorter than in the first option. However, 2 implants would be necessary to restore the missing mandibular molars. Furthermore, if the impacted second molars were diagnosed as having ankylosis, 4 implants would be required.

The third option was to preserve the first molars and extract the second molars, and the fourth option was to extract the first and second molars. These options have the potential risks of nerve damage and a large bone defect after extraction of the apically impacted second molars; this complicates prosthetic work. With the third option, the longevity of the first molars cannot be guaranteed because of severe root resorption. However, intrusion of the maxillary right second molar would be the only orthodontic procedure required; thus, the total treatment duration can be shortened.

These treatment alternatives were discussed with the patient. Because of his recent history of extraction of the mandibular third molars, he was reluctant to undergo additional extractions. Preservation of all mandibular molars would be ideal for this patient in spite of the long treatment duration and the possibility of ankylosis of the second molars and additional root resorption of the first molars. This treatment would yield a predictable outcome, unless the second molars were ankylosed. The infrabony defects around the first and second molars reportedly could be improved in association with orthodontic tooth movement. Furthermore, the treatment would allow the patient to maintain proprioception and adaptive capacity in the periodontal ligament space and not create a large bone defect at the impacted sites. Therefore, we selected the first option, and the patient gave signed informed consent for treatment.

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses