Third molar removal is the most frequently performed single procedure carried out by many oral and maxillofacial surgeons. Surveys have shown that over 80% of many oral and maxillofacial surgeons’ practice is taken up with dentoalveolar surgery, of which about 65% is removal of third molars. Indications for removal of unerupted third molars are identified in the Parameters and Pathways published by the American Association of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgeons and include :

- 1

Pain

- 2

Carious tooth

- 3

Pericoronitis

- 4

Facilitation of the management of or limitation of progression of periodontal disease

- 5

Nontreatable pulpal or periapical lesion

- 6

Acute and/or chronic infection (e.g., cellulitis, abscess)

- 7

Ectopic position (malposition, supraeruption, traumatic occlusion)

- 8

Abnormalities of tooth size or shape precluding normal function

- 9

Facilitation of prosthetic rehabilitation

- 10

Facilitation of orthodontic tooth movement and promotion of stability of the dental occlusion

- 11

Tooth in the line of fracture complicating fracture management

- 12

Tooth involved in surgical treatment of associated cysts and tumors

- 13

Tooth interfering with orthognathic and/or reconstructive surgery

- 14

Preventive or prophylactic removal, when indicated, for patients with medical or surgical conditions or treatments (e.g., organ transplants, alloplastic implants, bisphosphonate therapy, chemotherapy, radiation therapy)

- 15

Clinical findings of pulp exposure by dental caries

- 16

Clinical findings of fractured tooth or teeth

- 17

Impacted tooth

- 18

Internal or external resorption of tooth or adjacent teeth

- 19

Patient’s informed refusal of nonsurgical treatment options

- 20

Anatomic position causing potential damage to adjacent teeth

- 21

Use of the third molar as a donor tooth for tooth transplant

- 22

Tooth impeding the normal eruption of an adjacent tooth

- 23

Resorption of an adjacent tooth

- 24

Pathology associated with the tooth follicle

- 25

Abnormality of size or shape precluding normal function

Removal of Lower Third Molars

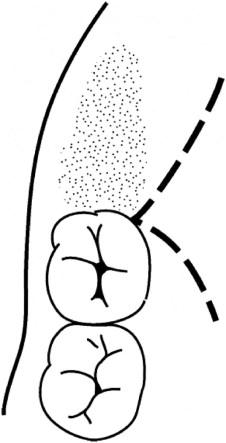

Techniques advocated for removal of unerupted or impacted lower third molars usually involve the raising of a buccal flap, which involves an incision down the external oblique ridge to the distobuccal line angle of the second molar, and then down into the buccal sulcus anterolaterally, terminating at the distal aspect of the first molar ( Fig. 15-1 ). If it carries forward any further than this in the buccal sulcus, a small bleeding vessel is often encountered, which can be troublesome. An alternative technique is to take an envelope flap around the gingival margin of the second molar, and even the first molar; sometimes this is augmented with an anterior relaxing incision ( Fig. 15-2 ). In some ways, it is felt to be preferable to utilize the buccal sulcus incision and not to compromise the gingival crevice around the second or first molars. A buccal flap is normally raised, which should not extend further inferior than is necessary, because although further raising this flap may marginally improve access, it does increase postoperative swelling. Techniques today do not advocate raising a lingual flap or placement of a lingual retractor, though advocates of this technique state that raising a lingual flap and placing a lingual retractor give improved access and visibility, and the incidence of permanent lingual nerve problems may decrease. However, it is accepted that placement of a lingual retractor may cause some short-term traction paresthesia to the lingual nerve. Bone removal is normally carried out with a drill, with advocates for either a round bur or a fissure bur. General techniques involve guttering around the lateral aspect of the third molar and also distobuccally. Care must be taken if one proceeds onto the distal aspect of the third molar or distolingually, because the lingual nerve can occasionally be encountered in this area. If the tooth will not now elevate from the socket, most authorities would advocate sectioning the tooth, either horizontally or vertically, depending on its position. Most techniques involve cutting through the tooth approximately two thirds to three quarters of the distance from the buccal to the lingual aspect of the tooth and then placing an instrument in the groove and cracking off the crown of the tooth such that the lingual plate is not penetrated, and therefore not endangering the lingual nerve. By knowing the length of the cutting portion of a fissure bur, one can calculate the correct depth to section the crown of the tooth without risking damage to the lingual nerve. Following removal of the crown, the roots can normally be elevated, although occasionally they may need to be separated and elevated independently. On completion of the tooth removal, the residual follicle should be removed with care, because, on the lingual side, the lingual nerve can occasionally be intimately related to follicular remnants, and in some cases, it is more expedient to leave follicular remnants behind, because the formation of a residual cyst from these remnants is an extremely rare occurrence. Following removal of follicular remnants, the lingual plate should be examined to ensure that it is in continuity and that the lingual nerve is not visible and damaged. The depth of the socket should also be inspected to see if the inferior alveolar nerve can be visualized and if it is intact. If a discontinuity defect of either nerve is seen, immediate repair is advocated. If the nerve is visualized, but not obviously damaged, the patient should still be followed up closely to assess for altered sensation postoperatively. Following debridement of the socket, the current standard of care does not require any material, either autogenous or allogenic, to be placed in the socket, and studies are not yet complete to show whether this is helpful in any way to ensure adequate bone formation in the third molar socket and whether it improves the periodontal condition around the distal aspect of the second molar. The residual socket can be sutured, but if sutures are to be placed, they should be superficial only, particularly on the lingual side, to avoid any involvement of a high lingual nerve, which occurs in about 15% of cases. A single 3/0 or 4/0 resorbable suture on a reverse cutting needle is preferred. Some authorities prefer not to suture the socket but rather to place a pack with it—for example, Terracortil, an antibiotic/steroid pack. Some substances placed in tooth sockets can be neurotoxic to the inferior alveolar nerve, if it is exposed in the socket. These include tetracycline paste and possibly Surgicel (due to its low pH).

Coronectomy

Coronectomy is a technique whereby the crown of the tooth and the coronal portion of the roots are removed, but the apical portion of the roots is retained. It also goes by the names of partial root retention, vital root retention, and partial odontectomy. It may be indicated when the apical portion of the roots of the tooth is in contact with vital structures and their removal might damage these structures. The most frequent example is the roots of the lower third molars and their relationship to the inferior alveolar nerve.

Traditionally, the relationship of the roots of a lower third molar to the inferior alveolar nerve has been judged from a Panorex radiograph, and criteria have been introduced to aid this evaluation. More recently, however, the advent of cone beam computed tomography (CBCT) scanning technology has enabled more information to be gathered on the exact relationship in three dimensions. It is considered that when the results of the cone beam CT scan might alter the treatment provided that it should be offered to a patient.

Although there are variations in the technique of coronectomy, certain common principles apply.

- •

The tooth involved should not be mobile.

- •

There should be no decay or infection involving the roots of the teeth.

- •

The tooth should be vital or adequately endodontically treated.

- •

The crown and the coronal portion of the roots should be removed until they are 2 to 3 mm below the surrounding crestal bone. Animal studies have shown that if this rule is followed bone will grow over the retained roots.

- •

No treatment of the exposed pulp is required.

- •

The retained portion of the root should not be mobilized during the coronectomy procedure.

Patients are normally placed on prophylactic antibiotics so that antibiotics are present in the pulp chamber as the tooth is sectioned. However, there are only a small number of papers describing the results of coronectomy, and not all of them used antibiotics.

In the technique, a buccal incision is made over the external oblique ridge of the mandible as in a conventional third molar approach (shown in Fig. 15-1 ). Buccal and lingual flaps are then raised and a lingual retractor is placed. The latter is done because the crown of the tooth must be fully sectioned and mobile before removal, and, if a retractor is not used, there is a risk of perforating the lingual plate and possibly damaging the lingual nerve. The lingual retractor should preferably be specifically designed with an appropriate shape and no sharp edges and with an adequate width to fully protect the lingual nerve.

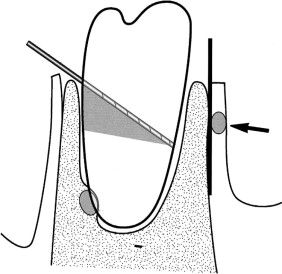

Once the retractor is positioned, a fissure bur is used at an angle of 45 degrees to section the crown. After the crown has been removed, the fissure bur is used to remove a portion of the remaining roots on the buccal side so that they are below the alveolar crest ( Fig. 15-3 ). The exposed pulp is not treated in any way. Primary closure of the socket is felt to be necessary even if a periosteal release has to be performed. A watertight seal is obtained using vertical mattress sutures. A radiograph is normally taken to ensure that tooth and root removal is adequate. The radiograph also serves as a baseline for later radiographs to assess bone formation over the roots.

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses