History of Tracheotomy

Tracheotomy has been known for approximately 3500 years, with proponents and opponents arising at different times in history. Early references advising relief for choking persons by cutting open the trachea were made 3500 years ago by Homer and Alexander the Great. For many years, the tracheotomy was considered a useless and dangerous procedure. In 1739, Heister described the operation in which he used a straight tube and trocar, and he remarked that the utility of this operation was widely neglected by modern surgeons. Resolution of many of the highly debated issues surrounding the tracheotomy began with Chevalier Jackson, who advocated a long incision, avoidance of high cartilage dissection, slow and deliberate surgery, and cutting of the thyroid isthmus. Today, the indications, techniques, and armamentarium for tracheotomy have evolved from thrusting a reed over the point of a sword into a choking soldier to the modern meticulous surgical procedure that predictably bypasses the upper airway for a variety of indications, both emergent and nonemergent.

Indications

The indications for tracheotomy fall in several general categories.

- 1

Need to bypass airway obstruction

- 2

Neck trauma

- 3

Subcutaneous emphysema that can lead to massive edema

- 4

Facial fractures

- 5

Airway edema (trauma, burns, infection, anaphylaxis, angioedema)

- 6

Need to provide a long-term route for mechanical ventilation

- 7

Pulmonary toilet (inadequate cough, secretion management, aspiration)

- 8

Extensive head and neck procedures

- 9

Severe sleep apnea

Indications

The indications for tracheotomy fall in several general categories.

- 1

Need to bypass airway obstruction

- 2

Neck trauma

- 3

Subcutaneous emphysema that can lead to massive edema

- 4

Facial fractures

- 5

Airway edema (trauma, burns, infection, anaphylaxis, angioedema)

- 6

Need to provide a long-term route for mechanical ventilation

- 7

Pulmonary toilet (inadequate cough, secretion management, aspiration)

- 8

Extensive head and neck procedures

- 9

Severe sleep apnea

Contraindications

There are no absolute contraindications to tracheotomy. However, there are instances, such as a high-riding innominate artery, goiter, or thyroid mass, that may alter the standard technique that may be employed. There are contraindications to percutaneous tracheotomy that will be discussed later.

Timing Of Tracheotomy

All surgeons involved in surgical procedures where general anesthesia is employed or where there is risk of airway loss should be prepared to secure a surgical airway. Preoperatively, the surgeon must consider the type of procedure and possible interventions and determine if a tracheotomy is necessary at the beginning of a procedure. Should there develop a potential for significant airway edema from the operation, tracheotomy can be reserved for the conclusion of the procedure, if determined to be necessary. Early tracheotomy may be beneficial in patients with severe craniomaxillofacial trauma or deep space neck infections.

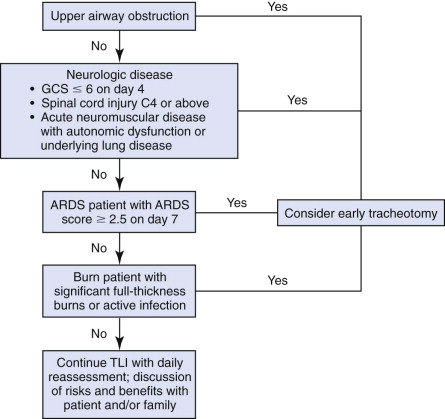

One of the most difficult decisions to make in the management of the mechanically ventilated patient is whether to continue translaryngeal intubation or to perform a tracheotomy. Reviews of the literature have concluded that there are not enough well-designed studies to establish guidelines regarding timing of tracheotomy. De Leyn et al concluded that in critically ill adult patients requiring prolonged mechanical ventilation, tracheotomy performed within the first week may shorten the duration of artificial ventilation and length of stay in the intensive care unit (ICU). King and Moores suggest using Heffner’s “anticipatory approach” ( Fig. 34-1 ). Patients likely to be taken off the ventilator in 7 to 10 days should continue with endotracheal intubation, whereas those who are likely to require longer ventilatory support should be considered for tracheotomy. When the duration of intubation cannot be predicted, patients should be reevaluated daily. At the end of the day, the decision must be individualized, giving consideration to the patient’s preferences and expected clinical course.

Elective Adult Tracheotomy: Anatomy And Technique

Elective tracheotomy is preferably performed under general anesthesia in the operating room after the airway is secured with endotracheal intubation or laryngeal mask airway (LMA). A shoulder roll is placed, and the head is extended to make the tissues of the neck taut and to distract the trachea from the thorax. This distraction of the larynx and trachea increases the distance from the cricoid cartilage to the sternal notch, which facilitates the identification of these landmarks.

Once the field is prepared in a sterile fashion, local anesthesia is administered along the planned incision line. A 3- to 4-cm transverse incision is made between the medial borders of each sternocleidomastoid muscle at a level approximately half the distance between the cricoid cartilage and the sternal notch. Blunt dissection with gauze is used in the subcutaneous plane to facilitate identification and avoidance of the anterior jugular veins. This maneuver is much quicker than blunt or sharp dissection with instruments and is less likely to cause bleeding that may complicate the postoperative course. Once the subcutaneous layer is dissected, the cervical fascia is identified; Then the median raphe between the paramedian sternohyoid and sternothyroid muscles is identified and dissected with blunt hemostats. Retractors are then used to retract the strap muscles laterally. The operator and assistant alternate vertical and horizontal spreading down to the trachea, with repositioning of the retractors as dissection proceeds toward the trachea. It is imperative that the trachea be maintained in the midline and that the retraction does not pull the trachea out of the field of dissection.

Once past the strap muscles, the middle cervical fascia is sometimes identified with the thyroid isthmus overlying the trachea. It is usually possible to retract the thyroid superiorly out of the field. Rarely does the thyroid isthmus need to be divided, but if necessary, it can be suture ligated or cauterized. One must be sure that good hemostasis is achieved to prevent any postoperative issues with thyroid bleeding. Once the trachea is seen through the pretracheal fascia, a cricoid hook is placed, and the trachea is elevated into the surgical field. This is the most critical portion of the operation and helps to stabilize the trachea and facilitates visualization. The pretracheal fascia is dissected off the trachea to visualize the tracheal rings.

After visualizing the trachea, the surgeon can determine the size of tracheotomy tube needed for the airway, typically, a No. 8 for a man and a No. 6 for a woman. The tube must be tested by the scrub nurse and lubricated. At this point, the surgeon may elect to place stay sutures in the tracheal rings, which can be draped onto the chest skin. The authors do not use stay sutures on adult patients.

After alerting the anesthesiologist, a scalpel is used to make a tracheal incision of choice: a vertical incision through rings two, three, and occasionally four; a horizontal incision between rings two and three; or a T -shaped incision. One must be careful to avoid lacerating the posterior tracheal wall or cutting too far laterally and potentially injuring the recurrent laryngeal nerve. Once the trachea is entered, a tracheal dilator is placed and deployed to aid passage of the tracheal tube. With the cricoid hook still in place and with direct visualization of the trachea, the tracheal tube is inserted. The insertion stylet is removed, and the anesthesia tubing is connected. Once end-tidal CO 2 and breath sounds are confirmed, the cricoid hook can be removed and the tracheal tube flange secured to the skin with sutures. One can also use tracheal ties if no microvascular surgery has been performed or is planned in the neck. A portable chest radiograph is obtained immediately postoperatively to verify proper positioning, as well as to assess for hemopneumothorax.

Complications Of Tracheotomy

Tracheotomy has a relatively low incidence of complications (roughly 15%), and most of these can be avoided by meticulous surgical technique and postoperative care. The complications can be defined by the interval from procedure to onset of complication(s) and stratified to the perioperative and postoperative periods. There is also a higher incidence of complications in those with medical or surgical comorbidities, such as in debilitated, obese, multiply injured, or burn patients. The most common complications are hemorrhage, tube obstruction, and tube displacement.

Perioperative Complications

Major hemorrhage during tracheotomy is uncommon and more frequently encountered in emergent tracheotomy. The incidence of operative and early hemorrhage is about 4%. Bleeding sites include the superficial anterior jugular veins, the thyroid isthmus, and the thyroid ima artery. Deeper bleeding lateral to the trachea can arise from the lateral vascular arcade that nourishes the trachea.

Paratracheal or pretracheal placement of the tracheal tube can be a significant intraoperative complication if manual control of the airway is not maintained until end-tidal CO 2 is confirmed. The tracheal tube can sometimes follow a false passage anterior or lateral to the trachea. It is usually rapidly identified by lack of CO 2 and breath sounds. To prevent this, clean dissection down to the trachea should be assured, the trachea should be visualized, and the cricoid hook should not be removed until verification of proper tube placement.

Pneumothorax is an uncommon complication and usually results from a difficult trachea or one with excessive lateral dissection, particularly in children. In cases where the airway is deviated due to infection, mass, or other etiology, the surgeon must be careful to avoid dissecting off course, inferiorly and laterally. A routine postoperative radiograph will detect a pneumothorax in most cases. Pneumothorax must be considered if ventilatory difficulty arises in a patient with a fresh tracheotomy; however, it is less likely than false passage or obstruction.

Other immediate complications include damage to adjacent structures, such as the esophagus or the recurrent laryngeal nerve (RLN). Damage to the RLN can be either by excessive lateral dissection, thermal injury from cautery, or from retraction injury. The esophagus may also be injured by overzealous incision into the trachea or excessive dissection, particularly if the trachea is being deviated by retraction or mass effect. Another potential complication is dissection made too far superiorly, with damage to the cricoid cartilage, particularly if a vertical tracheal incision is placed.

Postoperative Complications

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses