In the last decade or so there has been tremendous increased interest in male pattern baldness (MPB) and hair transplantation surgery. This can be attributed to many factors, primarily improvement in the results of hair transplant surgery through the use of micrografting techniques. In addition, medical therapy for MPB with the use of topical solutions such as minoxidil or the medication finasteride (Propecia) has helped increase public awareness and stimulated the search for other medical approaches to the treatment of MPB. Finally, vastly increased communication between surgeons performing hair transplantation and dramatic changes in medicine affecting cosmetic fields have served to organize and transmit the available knowledge about these procedures.

More than 50 years ago, Norman Orentreich authored a paper on MPB in which his most important observation was that grafts from the hair-bearing rim of the scalp were “donor dominant” and continued to grow hair when implanted into thinning or bald areas. Thus, the concept of multiple scalp grafts for the treatment of baldness has evolved. This movement of hair grafts from genetically preprogrammed, permanently growing sites to balding areas is the foundation of hair transplantation and micrografting as we know it today. This procedure, though used primarily for androgenetic alopecia (MPB), can also be used to cover scars secondary to scalp trauma or previous surgical procedures, radiation and thermal burns, and inactive phases of disease such as scleroderma and other cicatricial processes, as well as for some types of female alopecia. Because MPB is a genetically determined phenomenon, transplantation procedures move permanently growing scalp hair from the sides and back of the head (donor area) to appropriate recipient sites in the frontal, mid-scalp, and vertex regions.

Obviously, hair transplantation requires skill and a strong esthetic sense. Small micrografts and multifollicular grafts must be taken from areas that have excellent prospects for not losing the ability to grow hair during that individual’s lifetime. Because hairs grow in specific directions, grafts must be placed in a precise way so that not only does hair growth look full and natural but the pattern of growth also conceals or masks the graft recipient sites and proper angles are achieved for an attractive and complete result. Finally, each individual’s characteristics must be evaluated to create the most natural hairline and hair density while fully anticipating facial changes throughout the years.

Normal Hair Growth

Hair follicles initially appear in utero. No new follicles are created after birth, and none are lost in adult life. The only factors that change are the density of the follicles (which spread apart as the body surface increases with growth and weight gain) and the type of hair. The first hair to be produced by fetal hair follicles is lanugo hair, which is fine, soft, and unpigmented. This hair is usually shed by the eighth month of gestation.

The first postnatal hair is vellus hair, which is soft, fine, usually pigmented, and seldom more than 2 cm long. Vellus hair remains on the so-called hairless regions of the body such as the forehead and balding scalp. The only completely hairless surfaces are the palms, soles, glans penis, and mucocutaneous junctions.

Hair growth on the human scalp is a kind of mosaic of follicular activity with alternating patterns of growth (anagen) and rest (telogen) separated by a transitional (catagen) phase. Scalp hair grows about 0.3 mm/day, or 6 in/yr. Shedding of 50 to 150 hairs a day is considered normal. When hair is shed, it is replaced by new hair from the same follicle located just below the skin surface. Anagen can be initiated by plucking the telogen hair from a resting follicle or by wounding. Furthermore, certain hormones such as estrogen, progesterone, testosterone, and thyroid hormone influence hair growth.

Hair is composed primarily of keratin protein, the same material found in fingernails and toenails. The most striking feature of the protein of a hair’s central cortex is its cysteine content, which is much higher than that of the outer matrix proteins. Hair color depends on the number and type of melanosomes acquired from melanocytes migrating into the hair bulb matrix. In dark hairs, melanosomes are large, ellipsoid, and rich in melanin. In red hairs, they are spherical. White, gray, and blond hairs contain few or minimally pigmented melanosomes.

Male Pattern Baldness

MPB is the change from terminal hair to vellus hair. The true dimensions and complexity of this process have only recently been appreciated. The progress of MPB is not linear; the condition develops in fits and starts. Terminal hair progresses to vellus hair far past the age at which it was thought that one could delineate the extent of MPB. Surgeons performing hair transplant surgery today realize that it is not the dramatic changes in MPB that occur between the ages of 20 and 35, but what can take place from 40 to 50 years and beyond.

In whites, normal male pattern hair loss is noticeable in about 30% of men by the age of 30 years and in 50% of men by 50 years. Certain racial groups, including the Japanese, Chinese, American Indians, and some tribes of Africans, are relatively immune to the condition, which in whites follows a dominant trait with incomplete penetrance. Expression of this sex-limited gene depends on the level of circulating androgen. This hereditary incidence is noticeable not only in men but also in women who have a strong familial history of baldness.

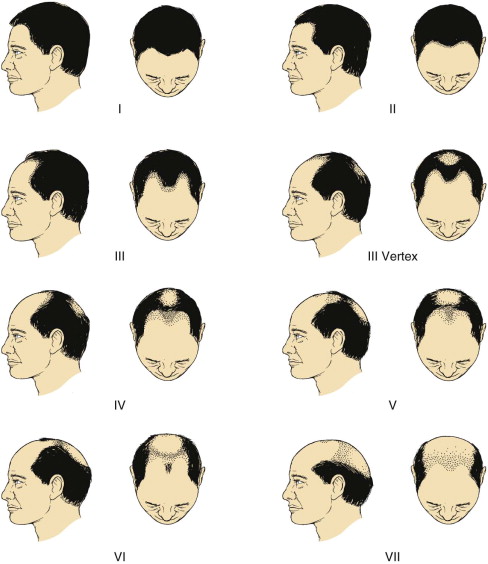

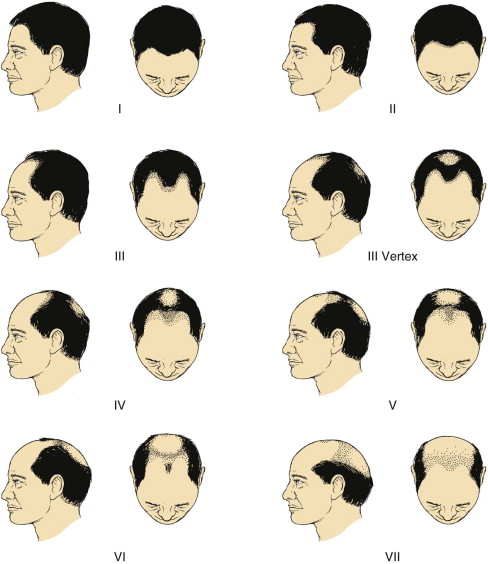

In men, hair loss can begin as early as the age of 20 years. With normal hair loss, one to several hundred hairs fall each day and are replaced by new hair. In the evolution of MPB, the new hair is fine and thin. Eventually, nothing is left on the scalp but the almost imperceptible fuzz of vellus hair. Simultaneously, hypertrophy of the sebaceous glands and hypersecretion of sebum usually occur and are provoked by androgenetic stimulation of the pilosebaceous follicles, which causes complete loss. MPB usually progresses in a definite pattern. First, the frontal hair regresses, and then loss of the more temporal hair becomes apparent with simultaneous thinning of the vertex. Ultimately, the most severe balding consists of total loss of the frontal and vertex hair. Norwood classified approximately seven different types of MPB. Identification of these types is key to an understanding of proper planning of hair transplantation surgery ( Fig. 106-1 ).

Dihydrotestosterone seems to be the specific hormone responsible for MPB. Genetic predisposition contributes to the topography of MPB because of the number of testosterone receptors on follicular cells and the activity of 5-alpha-reductase enzyme in different areas of the scalp. This enzyme reduces testosterone and inhibits protein synthesis by shortening the anagen phase, thereby producing finer and finer hair until it is eventually lost. Essentially, the hairs are gradually miniaturized in the presence of androgens, with large pigmented terminal hairs being replaced by thin depigmented hairs (vellus-like hairs)

Male Pattern Baldness

MPB is the change from terminal hair to vellus hair. The true dimensions and complexity of this process have only recently been appreciated. The progress of MPB is not linear; the condition develops in fits and starts. Terminal hair progresses to vellus hair far past the age at which it was thought that one could delineate the extent of MPB. Surgeons performing hair transplant surgery today realize that it is not the dramatic changes in MPB that occur between the ages of 20 and 35, but what can take place from 40 to 50 years and beyond.

In whites, normal male pattern hair loss is noticeable in about 30% of men by the age of 30 years and in 50% of men by 50 years. Certain racial groups, including the Japanese, Chinese, American Indians, and some tribes of Africans, are relatively immune to the condition, which in whites follows a dominant trait with incomplete penetrance. Expression of this sex-limited gene depends on the level of circulating androgen. This hereditary incidence is noticeable not only in men but also in women who have a strong familial history of baldness.

In men, hair loss can begin as early as the age of 20 years. With normal hair loss, one to several hundred hairs fall each day and are replaced by new hair. In the evolution of MPB, the new hair is fine and thin. Eventually, nothing is left on the scalp but the almost imperceptible fuzz of vellus hair. Simultaneously, hypertrophy of the sebaceous glands and hypersecretion of sebum usually occur and are provoked by androgenetic stimulation of the pilosebaceous follicles, which causes complete loss. MPB usually progresses in a definite pattern. First, the frontal hair regresses, and then loss of the more temporal hair becomes apparent with simultaneous thinning of the vertex. Ultimately, the most severe balding consists of total loss of the frontal and vertex hair. Norwood classified approximately seven different types of MPB. Identification of these types is key to an understanding of proper planning of hair transplantation surgery ( Fig. 106-1 ).

Dihydrotestosterone seems to be the specific hormone responsible for MPB. Genetic predisposition contributes to the topography of MPB because of the number of testosterone receptors on follicular cells and the activity of 5-alpha-reductase enzyme in different areas of the scalp. This enzyme reduces testosterone and inhibits protein synthesis by shortening the anagen phase, thereby producing finer and finer hair until it is eventually lost. Essentially, the hairs are gradually miniaturized in the presence of androgens, with large pigmented terminal hairs being replaced by thin depigmented hairs (vellus-like hairs)

Female Pattern Hair Loss

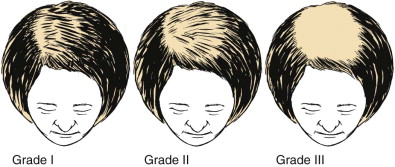

Like MPB, female pattern hair loss is most often due to heredity and aging. Hormonal influences in hereditary hair loss in women may be different from those in men, but researchers are continuing to study it. Unlike men, most women retain some of their natural hairline, which can be thickened to a delicate, yet fuller appearance.

Female pattern hair loss is not as obvious as MPB, but like men, it can be treated effectively. Frequently, women’s patterns are more diffuse or spread out over the entire scalp ( Fig. 106-2 ). Whether a female is a candidate for transplantation is determined at the initial consultation. A trained physician can also diagnose whether a woman is experiencing permanent female pattern hair loss and not temporary hair loss related to medical conditions such as pregnancy, disease, or stress.

Significant improvement in hairline definition, hair density, and facial esthetics can be achieved ( Figs. 106-3 and 106-4 )

Eyebrow Transplantation

The periorbital region has an important role in the perception of facial esthetics and proportion, and it also imparts volumes to facial expression and nonverbal communication. The causes of eyebrow loss can be mechanical, such as overzealous plucking, electrolysis, or laser hair removal; trauma; or medical conditions such as hormonal imbalance or alopecia universalis.

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses