CHAPTER 24 Removable Partial Denture Considerations in Maxillofacial Prosthetics

Maxillofacial Prosthetics

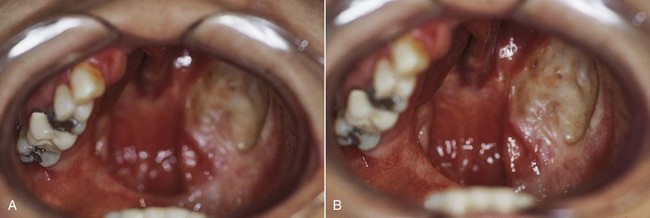

The maxillofacial patient can experience unique alterations in the normal oral/craniofacial environment; these result from surgical resections (Figure 24-1), maxillofacial trauma, congenital defects, developmental anomalies, or neuromuscular disease. In contrast to the above, when removable partial dentures are considered for these individuals, not only are tooth and tissue support considerations important, but the design must also take into account what impact the altered environment will have on prosthesis support, stability, and retention. In general, environmental changes reduce the capacity for residual teeth and tissue to provide optimum cross-arch support, stability, and retention.

Maxillofacial Classification

Patients can be categorized by maxillofacial defects that are acquired, congenital, or developmental. Acquired defects include those that are the result of trauma, or of disease and its treatment. These may include a soft and/or hard palate defect resulting from removal of a squamous cell carcinoma of the region (Figure 24-2). Congenital defects are typically craniofacial defects that are present from birth. The most common of these include cleft defects of the palate that may include the premaxillary alveolus. Developmental defects are those defects that occur because of some genetic predisposition that is expressed during growth and development (Figure 24-3). Such a classification order is helpful as patients within each category share similar characteristics (beyond those features specifically related to the prosthesis design), which become part of the total management plan. For example, prosthetic management of an adult who has experienced a maxillectomy procedure can be quite different from management of a patient with an unrepaired cleft palate.

Timing of Dental and Maxillofacial Prosthetic Care for Acquired Defects

Preoperative and Intraoperative Care

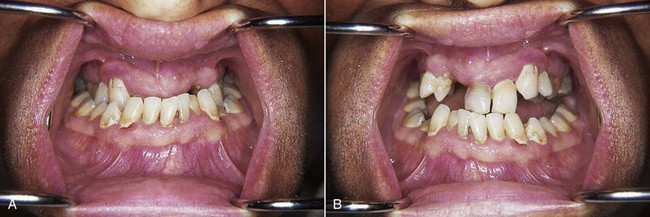

The planning of prosthetic treatment for acquired oral defects should begin before surgery. For the patient facing head and neck surgery, consideration should be given to dental needs that will improve the immediate postoperative course. Consequently, the prosthodontist who will help with management of the patient’s care should see the patient before surgery (Figure 24-4). The dental objectives of the preoperative and intraoperative care stages are to remove potential dental postoperative complications, to plan for the subsequent prosthetic treatment, and to make recommendations for surgical site preparation that improve structural integrity. Important patient benefits of such a preoperative consultation include the opportunity to develop the patient-clinician relationship, to discuss the functional deficits associated with the anticipated surgical procedure, and to describe how and to what extent the stages of prosthetic management will address them. The benefit from a prosthesis standpoint is that strategically important teeth, for definitive and/or interim prosthesis use, can be discussed with the surgical team and treatment planned for preservation.

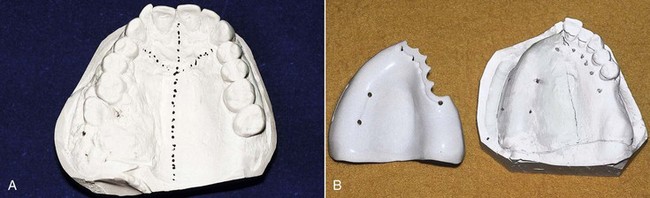

Impressions are made of the maxillary and mandibular arches to provide a record of existing conditions and occlusion to allow fabrication of immediate or interim prostheses (Figure 24-5) and to assess the need for immediate and delayed modification of the teeth or adjacent structures to optimize prosthetic care. It is important at this stage to begin planning for the definitive prosthesis because the greatest impact on the success of the maxillofacial prosthesis stems from the integrity of the remaining teeth and surrounding structures.

Interim Care

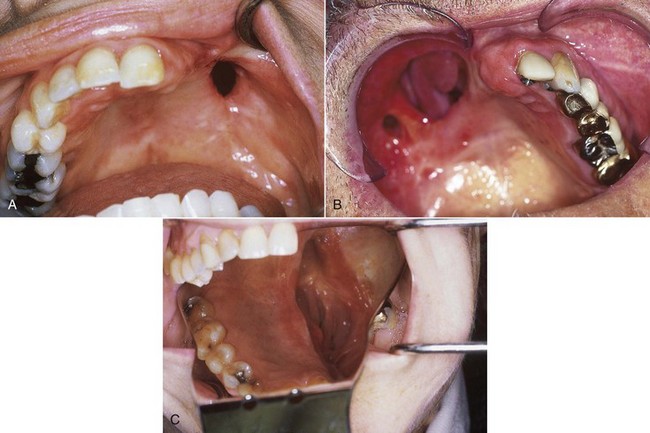

The typical maxillary acquired defect results in oral communication with the nose and/or maxillary sinus, although the composition of the surgical defect may vary widely (Figure 24-6). This creates physiologic and functional deficiencies in mastication, deglutition, and speech. Such defects have a negative impact on the psychological disposition of patients, especially if the defect also affects cosmetic appearance. The major deficiencies directly addressed by prosthetic management at this interim care time are deglutition and speech. This immediate postsurgical time is very challenging for patients, and it is important that they have been mentally prepared for it during the preoperative period. However, even with preliminary discussion, the impact of the surgery is often very distressing. An initial focus on improvement in swallowing and speech with the interim prosthesis can help boost the rehabilitation process significantly.

A prosthesis can be provided at surgery (see Figure 24-5B). Such a surgical obturator prosthesis is placed at the time of surgical access closure and serves to control the surgical dressing and split-thickness skin graft during the immediate postsurgical period. Such prostheses are best stabilized by appropriate wiring to remaining teeth or alveolar bone, or they may be suspended from superior skeletal structures. For some patients who have teeth remaining, such an immediate surgical prosthesis could be retained by wires in the prosthesis that engage undercuts on the teeth and would be removable; however, the ability to control the surgical dressing may be less predictable with such an approach. Immediate placement of a prosthesis has been suggested to improve patient acceptance of the surgical defect, although no measure of this psychological impact has been shown; this method offers greater assurance of adequate nourishment by mouth—potentially precluding the use of a nasogastric tube.

It may be preferable to stabilize the surgical dressing by suturing a sponge bolster to provide stabilization to the split-thickness skin graft. Following the primary healing stage, the sponge with packing (or the immediate prosthesis if used) is removed by the surgeon and an interim obturator prosthesis can be placed (Figure 24-7). For the patient who has been provided with bolster obturation, the presurgical prosthodontic evaluation is very important to ensure that the patient is prepared for the transition from bolster to prosthesis, and to ensure that plans for the prosthesis are made, especially if an interim prosthesis is to be fabricated. Interim prostheses are wire-retained resin prostheses that generally do not have teeth initially but may be modified with the addition of teeth after an initial period of accommodation (Figure 24-8).

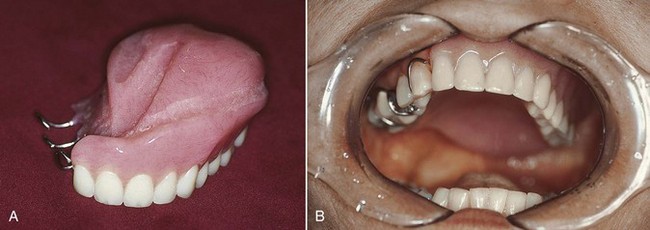

When surgical defects become large, as in a near-total maxillectomy defect, prosthesis support, stability, and retention are not likely to be satisfactory unless extension into the defect can be accomplished. When teeth remain, the impact of the defect size is somewhat lessened. But when the remaining teeth are few or are located unilaterally in a straight line (see Figure 24-1), the mechanical advantage for prosthesis stability is less. The ability of the defect tissue to offer the needed mechanical characteristics to the interim prosthesis is unpredictable at best. It is this patient who benefits the most from a well-planned surgery that preserves oral and defective anatomy to the advantage of the prosthesis.

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses