Regional odontodysplasia is a rare and unique dental anomaly involving both dentitions, but mostly the teeth of 1 quadrant. This report describes the combined surgical and orthodontic treatment of a boy with regional odontodysplasia. The mandibular right central and lateral incisors and the canine (as well as the deciduous predecessors) were affected. In a 2-step procedure, the maxillary right and left second premolars were autotransplanted to the affected area. The extraction sites in the maxilla were closed, and a good functional occlusion was established.

Regional odontodysplasia is a rare and unique dental anomaly involving both dentitions, mostly the teeth of 1 quadrant. The term “odontodysplasia” was described by Zegarelli et al in 1963. The prefix “regional” was added by Pindborg in 1970. Differential diagnoses might be oculodentodigital dysplasia, segmental odontomaxillary dysplasia, odonto-onycho-dermal dysplasia, or odontochondrodysplasia.

Dental regional odontodysplasia involves the hard tissues of the teeth that are derived from both epithelial (enamel) and mesenchymal (dentin and cementum) components of the tooth-forming apparatus in groups of contiguous teeth. It is an unusual, nonhereditary developmental anomaly of tooth formation that characteristically affects enamel and dentin formation of the deciduous or permanent dentition. The characteristic findings are discolored soft teeth accompanied by gingivitis, swelling, or abscess. Enamel and dentin are hypomineralized and hypoplastic, so that the “ghost teeth” appear shadowy, with wide pulp chambers, in radiographs.

The bizarre pulpal morphology seen radiographically as high pulp horns extending to the occlusal surface could provide open communication between the pulpal tissue and the oral cavity. Eruption of the affected teeth is delayed or might not happen.

The etiology is unknown. Epidemiologic data are rare; 138 cases of regional odontodysplasia have been published up to 2004, and reports on ultrastructure are few. The sex ratio of females to males was 1.7 to 1. The age at diagnosis ranged between 4 and 23 years. The maxilla was more often affected (maxilla to mandible ratio, 1.6:1). In 47.1% of the patients, the deciduous and permanent dentitions were affected. In 93.4% of the patients, the affected teeth lay side by side. Missing teeth were observed in 10.7%. Failure of tooth eruption of regional odontodysplasia teeth occurred in 39.7%.

There is a predilection for the anterior teeth. Because of the poor quality of the affected teeth, they cannot be restored adequately. Therefore, the treatment of choice is extraction with prosthetic replacement. Necrosis and facial cellulitis appear to be complications if these teeth are retained.

Histologically, areas of hypocalcified enamel are visible, and enamel prisms appear irregular in direction. Coronal dentin is fibrous, consisting of clefts and fewer dentinal tubules; radicular dentin is generally more normal in structure and calcification.

Pathologic mineralizations involving prismatic structures, which affect the size, shape, and stoichiometric structure of crystallites and lead to enhanced magnesium-to-calcium and sodium-to-calcium ratios and crystal defects, were observed.

The histologic examination of 1 patient showed widespread globular dentin, calcifications in the enlarged pulp chambers, and hypoplastic and hypomineralized enamel. Enamel and dentin are grossly altered in regional odontodysplasia, but cementum is less affected, and soft-tissue calcifications are associated with odontogenic cytokeratin-positive epithelial remnants, in addition to mesenchymal components.

The results of a study of gingival tissue around the follicle showed evidence of the role of the matrix metalloproteinases and their natural inhibitors by resident cells in this pathosis. An imbalance in the amounts of matrix metalloproteinases and their natural inhibitors was associated with the pathologic breakdown of the collagen.

Cahuana et al concluded that therapeutic decisions during childhood should be based on the degree of involvement and each patient’s functional and esthetic needs. Autotransplantation might be a good partial treatment option during the mixed dentition in some patients. Definitive treatment would include prosthetic rehabilitation with implants once the patient reaches adulthood.

A 6-year follow-up of a patient with regional odontodysplasia treated by autotransplantation of 3 premolars was presented by von Arx. Our report describes the combined surgical and orthodontic treatment of a boy with regional odontodysplasia that affected the mandibular right central and lateral incisors and the canine (as well as the deciduous predecessors). The maxillary right and left second premolars were autotransplanted to the affected area in a 2-step procedure. The extraction sites in the maxilla were closed, and a good functional occlusion was established.

Diagnosis and etiology

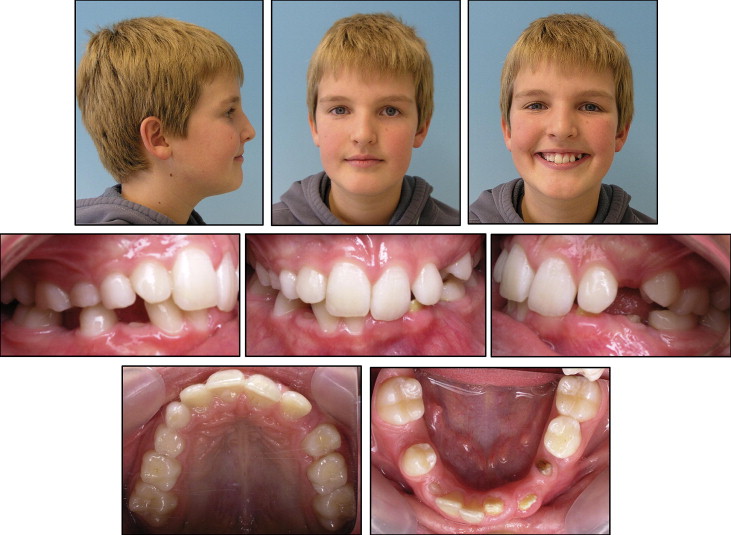

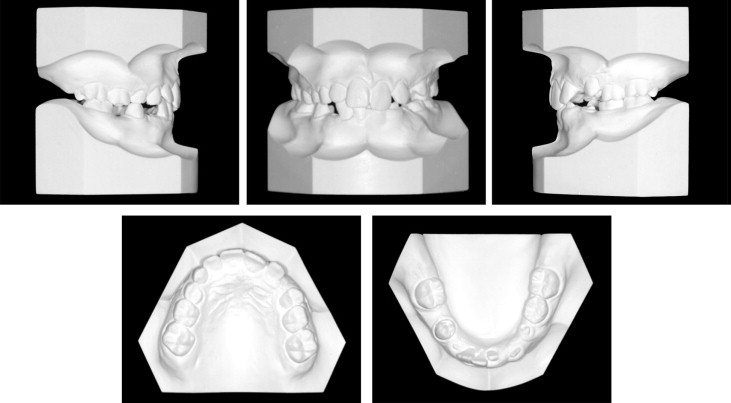

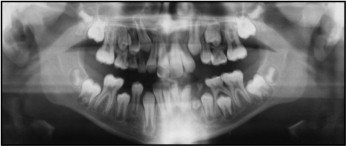

The patient, a boy aged 7 years 5 months, was transferred by his general dentist for the implementation of a space maintainer because of premature loss of the mandibular left lateral deciduous incisor and canine. The mandibular right second deciduous molar and left first deciduous molar were decayed, the maxillary right first permanent molar had not yet erupted, and the mandibular left central permanent incisor had hypocalcified enamel. In the panoramic radiograph, all permanent teeth except the third molars were visible. However, the germs of the mandibular left lateral permanent incisor and canine and partially the central incisor appeared foggy, like “ghost teeth.” The occlusion showed a neutral relationship. A removable space maintainer was placed in the mandible and regularly checked. Definitive treatment planning was postponed.

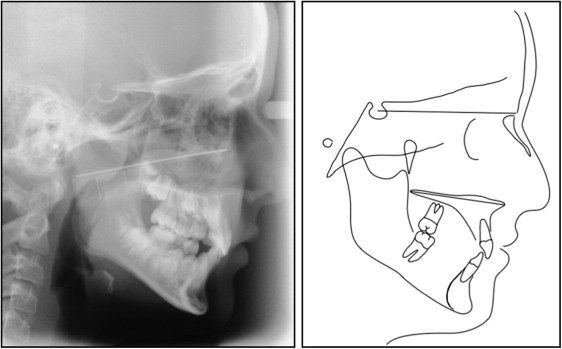

At age 10 years 2 months, new diagnostic records were evaluated for treatment planning ( Figs 1-4 ). The patient’s general medical history showed no pathologic findings. The Angle Class I occlusion was combined with space deficits for the maxillary left permanent canine and the mandibular right second permanent premolar. The maxillary and mandibular incisors had been retruded by the high tension of the perioral musculature. Due to reduced crown length of the mandibular left central incisor, the antagonist maxillary left central incisor had already extruded, causing a cant of the occlusal plane down on the left side in the frontal view.

There was no asymmetry of the face and no midline deviation of the dental arches. Manual structure analyses of the temporomandibular joints showed no pathologic findings. Examination of the lateral cephalometric radiograph showed a retrognathic maxilla (SNA, 77°) and a neutral vertical position of the jaws (NSL-ML, 32°). In the panoramic radiograph, all third molars were present; the germs of the mandibular left lateral permanent incisor and permanent canine appeared as “ghost teeth,” and the root of the mandibular left central permanent incisor was short. These findings contributed to the diagnosis of regional odontodysplasia.

The possibility of autogenous tooth transplantation was explained to the mother and the patient. For further information, the patient was transferred to the second author (F.W.N.), head of the maxillofacial surgery department at the University of Erlangen in Germany. He supported the orthodontic treatment plan including the transplantation of the 2 maxillary premolars to the area of the regional odontodysplasia. Because the development of the premolar roots was not advanced sufficiently, a mandibular space maintainer was used to stabilize the situation for 1 year while waiting for the desired developmental stage of the roots. The root should be developed up to two thirds or three quarters of the final length for autotransplantation.

Treatment objectives

The treatment objectives were to maintain the bone of the alveolar process and to prevent bone atrophy after removal of the “ghost teeth.” In the worst-case scenario after skeletal maturation, good bony conditions would be well-prepared for implants, avoiding temporary removable and, later, fixed prostheses. In the best-case scenario, the need for later prosthetic treatment would be avoided or minimized. Ideally, one’s own teeth—with positive vitality—can be used to restore the gap created by removal of the “ghost teeth.” Furthermore, the space deficit in the maxilla would be resolved. Also, a good functional occlusal result with healthy temporomandibular joints and an attractive facial appearance would be established.

Treatment objectives

The treatment objectives were to maintain the bone of the alveolar process and to prevent bone atrophy after removal of the “ghost teeth.” In the worst-case scenario after skeletal maturation, good bony conditions would be well-prepared for implants, avoiding temporary removable and, later, fixed prostheses. In the best-case scenario, the need for later prosthetic treatment would be avoided or minimized. Ideally, one’s own teeth—with positive vitality—can be used to restore the gap created by removal of the “ghost teeth.” Furthermore, the space deficit in the maxilla would be resolved. Also, a good functional occlusal result with healthy temporomandibular joints and an attractive facial appearance would be established.

Treatment alternatives

Three main treatment alternatives were presented to the mother and the patient.

- 1.

Align the maxillary arch, wait until the “ghost teeth” erupt, and try conservative dental treatment. In case of failure, a removable prosthesis could be used while awaiting a definitive dental solution with implants. Alternatively, the mandibular left first permanent premolar could be moved forward 1 lower incisor so that conventional bridgework would be possible later as an alternative to implants.

- 2.

Remove the 2 maxillary premolars and the germs of the mandibular left lateral permanent incisor and permanent canine. Shift the mandibular midline 1 lower incisor to the left and make a crown on the hypocalified mandibular left central permanent incisor, with mesial movement of the teeth in the fourth quadrant and closure of the extraction sites in the maxilla and the left side of the mandible from the distal aspect.

- 3.

Remove 1 premolar in the first, second, and fourth quadrants. One of these premolars would be used as an autogenous tooth transplant in the region of the “ghost teeth.” The extraction sites would be closed orthodontically.

Treatment progress

As a first treatment step at the University of Erlangen when the patient was 11 years 8 months, the mandibular left lateral permanent incisor and the maxillary left first deciduous molar and the germ of the mandibular left permanent canine were removed, and the maxillary left second premolar was transplanted to the site of the mandibular left canine ( Fig 5 , A ). The maxillary left second premolar had to be implanted at a 90° rotation, because of insufficient bone support in the transverse direction of the alveolar process. The fixation of the transplanted tooth was accomplished with loose sutures.

One month later, orthodontic treatment was initiated. For occlusal protection, bite ramps were bonded palatally on the 2 maxillary central permanent incisors. To minimize friction, the 0.022-in Speed System (Strite Industries, Cambridge, Ontario, Canada) was selected. The mandibular teeth from the left to the right first premolars were bonded. The initial archwire was a 0.016-in supercable (Strite Industries). This was followed by an 0.018-in supercable archwire.

Two months after the start of orthodontic treatment, fixed appliances were placed in both arches. The next series of archwires placed in the mandible were 0.016-in nickel-titanium, 0.016 × 0.016-in nickel-titanium, 0.016 × 0.016-in stainless steel, and 0.016 × 0.022-in stainless steel. In the maxilla, the sequence was 0.016-in supercable, 0.016-in nickel-titanium, 0.016-in stainless steel, 0.016 × 0.016-in stainless steel with anti-Spee activation, 0.016 × 0.022-in stainless steel with anti-Spee activation, and 0.017 × 0.025-in stainless steel.

At the University of Erlangen 1 year 5 months after the transplantation of the maxillary left second premolar, the hypoplastic mandibular left central incisor was extracted, and the maxillary right second premolar was transplanted to the region of the mandibular left incisors ( Fig 5 , B ). After 2 months. a 0.016 × 0.022-in stainless steel archwire and power chains were used to initiate the closure of the extraction sites in the maxilla.

One month later, the position of the bracket of the transplanted maxillary left second premolar was optimized, the transplanted maxillary right second premolar was bonded, and a 0.016-in supercable archwire was inserted ( Fig 5 , C ). Because of the tendency for a scissors-bite of the transplanted teeth, a 0.010-in nickel-titanium Biostarter archwire (Forestadent, Pforzheim, Germany) was selected, because an inset for these teeth could be bent in the nickel-titanium wire permanently with help of the “Memory-Maker” (Forestadent).

The next archwires in the mandibular arch were 0.016-in nickel-titanium and 0.016 × 0.016-in stainless steel with inset correction bends for the transplanted teeth ( Fig 6 ). After that, Class III elastics (3/16 in, 4.5 oz) on the right side were used for midline correction and closure of the extraction site in the maxilla for 2 months.