Thanks to water fluoridation, improved medical and dental care, and the availability of antibiotics the incidence of severe head and neck infections is decreasing. Nonetheless, serious and life threatening infections still occur at unpredictable times. Therefore, the oral and maxillofacial surgeon must remain continually up to date by periodic study of the evolving diagnostic studies, surgical principles, and treatment techniques for infections. Conscientious application of the principles discussed below may not guarantee a favorable outcome of every serious case of head and neck infection that we may encounter; but by using them, surgeons may rest assured that their treatment has met the standard of care.

Etiopathogenesis—Causative Factors

In a recent study of severe odontogenic infections, caries and resulting periapical infection was the most frequent predisposing dental disease, most frequently arising in the mandibular posterior teeth. In contrast to other studies, pterygomandibular space infection was diagnosed more frequently than the submandibular space (59% versus 54% of cases). The lateral pharyngeal space was involved in a surprising 43% of cases, by extension from the pterygomandibular space.

Odontogenic and sinus infections tend to cause deeply seated abscesses because they introduce abscess-forming bacteria into deep structures that do not have natural drainage pathways. In the case of sinusitis, for example, the natural drainage pathways can become obstructed due to mucosal edema, thus setting up the cascade of infection, soft tissue edema, tissue necrosis within a closed compartment, resorption of bone, and finally the spread of infection into surrounding soft tissue compartments.

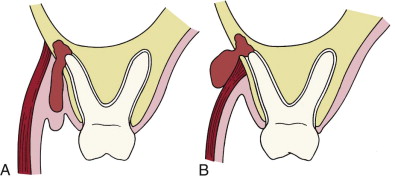

The spread of dental infection from the jaws is determined by the relationship of the tooth apex to the nearby muscle attachments. For example, as shown in Figure 117-1, A , periapical infection may pass through the bony cortical plate superior to the attachment of the buccinator muscle to form a buccal space abscess. If the perforation is on the inferior side of the buccinator muscle ( Figure 117-1, B ), then the infection will spread into the vestibular space.

Pathologic Anatomy

The deep fascial spaces of the head and neck can be divided into five related groups of spaces as outlined in Table 117-1 . The anatomic boundaries and relationships of the individual spaces are described in Tables 117-2 and 117-3 .

| GROUP OF SPACES | COMPONENT SPACES |

|---|---|

| Subcutaneous |

|

| Perioral |

|

| Perimandibular |

|

| Masticator |

|

| Deep neck spaces |

|

| Mediastinal |

|

| SPACE | BORDERS | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ANTERIOR | POSTERIOR | SUPERIOR | INFERIOR | SUPERFICIAL OR MEDIAL * | DEEP OR LATERAL † | |

| Buccal | Corner of mouth | Masseter m Pterygomandibular Sp. |

Maxilla Infraorbital Space |

Mandible | Subcutaneous tissue and skin | Buccinator m |

| Infraorbital | Nasal cartilages | Buccal space | Quadratus labii superioris m | Oral mucosa | Quadratus labii superioris m | Levator anguli oris m Maxilla |

| Submandibular | Ant belly digastric m | Post. belly digastric m. Stylohyoid m Stylopharyngeus m. |

Inf. and medial surfaces of mandible | Digastric tendon | Platysma m, Investing fascia | Mylohyoid Hyoglossus sup constrictor muscles |

| Submental | Inf border of mandible | Hyoid bone | Mylohyoid m | Investing fascia | Investing fascia | Ant bellies digastric mm. † |

| Sublingual | Lingual surface of mandible | Submandibular space | Oral mucosa | Mylohyoid m | Muscles of tongue * | Lingual surface of mandible † |

| Pterygomandibular | Buccal space | Parotid gland | Lateral pterygoid m | Inf border of mandible | Med pterygoid muscle * | Ascending ramus of mandible † |

| Submasseteric | Buccal space | Parotid gland | Zygomatic arch | Inf. border of mandible | Ascending ramus of mandible * | Masseter m † |

| Lateral pharyngeal | Sup and mid pharyngeal constrictor mm | Carotid sheath and scalene fascia | Skull base | Hyoid bone | Pharyngeal constrictors and retropharyngeal space | Medial pterygoid m † |

| Retropharyngeal | Sup and mid pharyngeal constrictor mm | Alar fascia | Skull base | Fusion of alar and prevertebral fasciae at C6-T4 | Carotid sheath and lateral pharyngeal space † |

|

| Pretracheal | Sternothyroid-thyrohyoid fascia | Retropharyngeal space | Thyroid cartilage | Superior mediastinum | Sternothyroid-thyrohyoid fascia |

Visceral fascia over trachea and thyroid gland |

| SPACE | LIKELY CAUSES | CONTENTS | NEIGHBORING SPACES | APPROACH FOR I & D |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Buccal |

|

|

|

|

| Infraorbital | Upper cuspid |

|

Buccal | Intraoral |

| Submandibular | Lower molars |

|

|

Extraoral |

| Submental |

|

|

Submandibular (on either side) | Extraoral |

| Sublingual | Lower bicuspids Lower molars Direct trauma |

Sublingual glands Wharton’s ducts Lingual n. Sublingual a. and v. |

Submandibular Lateral pharyngeal Visceral (trachea and esophagus) |

Intraoral Intraoral-extraoral |

| Pterygomandibular |

|

|

|

|

| Submasseteric |

|

Masseteric a. and v. |

|

|

| Infratemporal & deep temporal | Upper molars |

|

|

|

| Superficial temporal |

|

|

|

|

| Lateral pharyngeal |

|

|

|

|

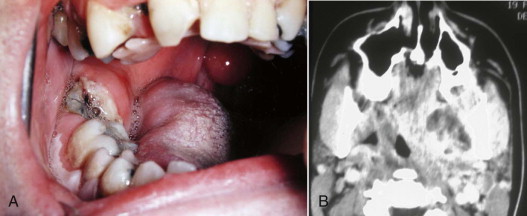

The subcutaneous space contains all tissues between the skin and the superficial layer of the deep cervical fascia. In the face, this includes the buccal and infraorbital spaces as well. The buccal space lies between the buccinator muscle and the skin. The infraorbital space lies between two heads of the quadratus labii superioris muscle, the levator labii superioris, and the levator anguli oris. It communicates laterally with the buccal space. Infection can pass around the medial or lateral side of the levator labii superioris at the infraorbital rim to enter the periorbital space, another portion of the subcutaneous space. Infection in the infraorbital space may therefore pass freely into the periorbital, buccal, and even the superficial temporal spaces by following the leaflet of the buccal fat pad that rises superiorly into the superficial temporal space. Such an infection is illustrated in Figure 117-2 .

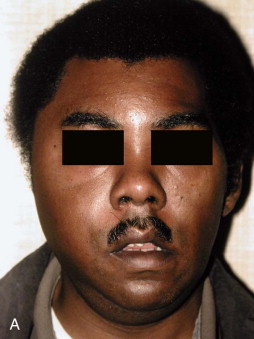

The perimandibular spaces were originally described as the submaxillary space by Grodinsky and Holyoke. Infectious involvement of all the perimandibular spaces (submandibular, submental, and sublingual) has been termed Ludwig’s angina. Infection in one of the perimandibular spaces may rapidly spread into the others by passing around the muscles that divide these spaces. In Figure 117-3 , the left submandibular space infection in this patient has spread around the anterior belly of the digastric muscle to involve the submental space.

The masticator space was originally described as a unitary compartment. Clinically, however, infections usually involve only one of its four components (submasseteric, pterygomandibular, superficial temporal, deep temporal.) Nonetheless, the masticator space, taken as a whole, was the most frequently involved deep fascial space in a recent study, at 78% of cases.

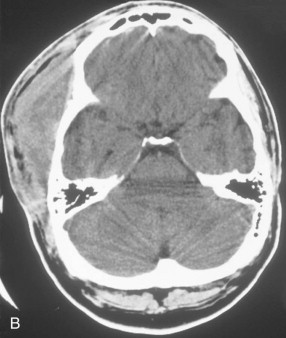

A clinical photograph of an infection involving each of these components, along with a corresponding CT image of infection in that component is seen in Figures 117-4 to 117-6 .

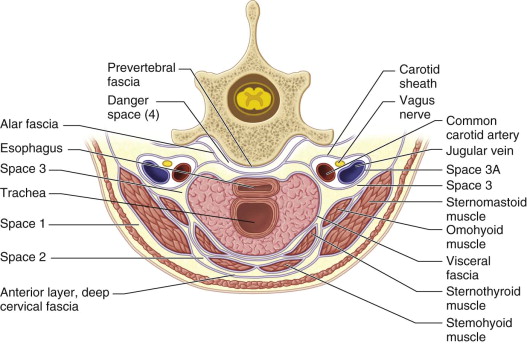

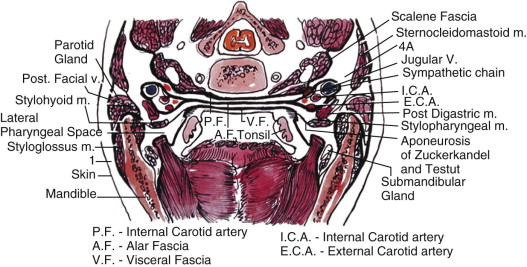

The deep neck spaces (lateral pharyngeal, retropharyngeal, and pretracheal) were described as Space 3 by Grodinsky and Holyoke. These potential anatomic spaces lie superficial to the visceral division of the middle layer of the deep cervical fascia. The visceral division of this fascia surrounds the trachea, esophagus, and thyroid gland inferior to the hyoid bone, as shown in Figure 117-7 . Superior to the hyoid bone, the visceral division is known as buccopharyngeal fascia. This fascial layer lies on the superficial (skin) side of the pharyngeal constrictor muscles. The fascial layers defining the lateral pharyngeal space are illustrated in Figure 117-8 .

The lateral pharyngeal space lies between the buccopharyngeal fascia and the medial pterygoid muscle. In this region, the aponeurosis of Zuckerkandl and Testut separates the lateral pharyngeal space into anterior and posterior compartments. The anterior compartment contains only areolar connective tissue, and can be safely drained intraorally. The posterior compartment contains the carotid sheath, and its lateral border is the parotid gland. The inferior extent of the lateral pharyngeal space is at the hyoid bone, where swelling may be externally visible.

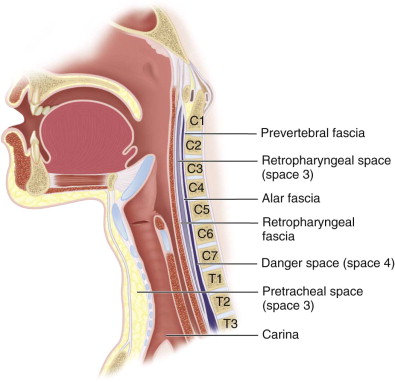

The retropharyngeal space lies between the buccopharyngeal (above the hyoid bone) or retropharyngeal fascia (below the hyoid bone) and the alar fascia, as shown in Figure 117-9 . The retropharyngeal fascia fuses with the alar fascia at a variable level between the 6th cervical and 4th thoracic vertebrae, forming the bottom of the retropharyngeal space. When an infectious process contacts this anatomic barrier, it may rupture through the alar fascia and enter the danger space.

The pretracheal space is not frequently involved in head and neck infections. It is the potential space between the trachea and the thyroid gland and the more superficial cervical strap muscles. It communicates laterally with the retropharyngeal space between the inferior thyroid artery and the thyroid cartilage. Importantly, however, the inferior portion of the pretracheal space communicates with the superior mediastinum, and below that the anterior mediastinum.

Head and neck infections can also spread via vascular channels, especially the valveless veins of the head and neck. Septic thrombophlebitis may thus ascend into the dural venous sinuses counter to the normal flow pattern. Cavernous sinus thrombosis may rarely arise from infection in facial and neck veins. The anterior route involves the angular vein, passing through the infraorbital space, or the ophthalmic veins in orbital infections. Odontogenic or maxillary sinus infections may enter the angular vein in the face, and ethmoid sinus infections may pass through the lamina papyracea on the medial wall of the orbit to enter one of the ophthalmic veins. From there, infectious thrombophlebitis can follow the ophthalmic vein through the superior orbital fissure into the cavernous sinus.

The posterior route to the cavernous sinus involves the posterior facial vein, possibly due to buccal or infratemporal space infection. The posterior facial vein drains into the pterygoid plexus, from which emissary veins pass through the foramina of Vesalius, ovale, and lacerum to join the inferior petrosal sinus and then the cavernous sinus.

Recently, Lemierre syndrome has been described as a cause of cavernous sinus thrombosis via the internal jugular vein, which drains the inferior petrosal sinus. Lemierre syndrome is a septic thrombophlebitis of the internal jugular vein, usually resulting from peritonsillar infection. Odontogenic infection may also cause Lemierre syndrome by involvement of the lateral pharyngeal space. The usual presentation of Lemierre syndrome is due to septic emboli that follow the usual flow pattern to the heart, where they are distributed to the lungs, liver, bone, and joints, causing metastatic abscesses. Fusobacterium necrophorum is the most frequently identified pathogen. More recently, however, other bacteria, especially of the genus Fusobacterium , have been associated with this condition. Anticoagulation and appropriate surgical therapy are used.

Although dental infections have been implicated in central nervous system (CNS) infections, such as cavernous sinus thrombosis and brain abscess, the majority of CNS infections arise from the paranasal sinuses. The most frequent cause of cavernous sinus thrombosis is sphenoid sinusitis, via emissary veins that perforate the thin layer of bone separating these two structures. In similar fashion, most brain abscesses are caused by infection of the paranasal air cavities lying directly opposite the site of brain abscess.

Pathologic Anatomy

The deep fascial spaces of the head and neck can be divided into five related groups of spaces as outlined in Table 117-1 . The anatomic boundaries and relationships of the individual spaces are described in Tables 117-2 and 117-3 .

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses