-

Outline

![]()

Accurate diagnostic information forms the foundation of any treatment plan. This information comes from several sources: the patient history and physical examination, the clinical and radiographic examination, and other diagnostic sources. The dentist must critically analyze the information before recommending treatment options to the patient. The goal of this chapter is to discuss both the types of data that the dentist in general practice typically collects and the ways in which the dentist evaluates and documents this information in preparation for creating a treatment plan. There are several types of examinations ( Box 1-1 ), and the focus of this chapter is on the comprehensive assessment of a patient.

The dentist should be able to provide several types of examinations for adolescent and adult patients. Most new patients to a dental office without urgent concerns will require a comprehensive examination before beginning treatment. A comprehensive examination includes a review and analysis of the patient’s health history and chief concerns, radiographic examination of the teeth and surrounding tissues, and clinical evaluation of the intraoral and extraoral hard and soft tissues. A periodic examination is performed at regular intervals, commonly during recall visits, for patients who have had a comprehensive or prior periodic examination. Activities include updating general and oral health histories and examination of extraoral hard and soft tissues. A problem-focused examination is limited to evaluating a specific problem or concern presented by the patient—for example, the evaluation of pain, swelling, broken teeth, or damaged restorations.

Overview of the diagnostic process

The diagnostic process is begun by gathering information about the patient and creating a patient database that will serve as the basis for all future patient care decisions. Although the components of each patient’s database vary, each includes pieces of relatively standard information, or findings, that come from asking questions, reviewing information on forms, observing and examining structures, performing diagnostic tests, and consulting with physicians and other dentists.

Findings fall into several categories. Signs are findings discovered by the dentist during an examination. For instance, the practitioner may observe that a patient has swollen ankles and difficulty in breathing when reclined, signs suggestive of congestive heart failure. Findings verbally revealed by the patients themselves, usually because they are causing problems, are referred to as symptoms . Patients may report such common symptoms as pain, swelling, broken teeth, loose teeth, bleeding gums, or esthetic concerns. When a symptom becomes the motivating factor for a patient to seek dental treatment, it is referred to as the chief complaint or chief concern . Patients who are new to a practice or presenting for emergency dental care often have one or more chief concerns ( Figure 1-1 ).

The clinician must evaluate findings individually and in conjunction with other findings to determine whether the finding is significant. For example, the finding that a patient is being treated for hypertension may be not be significant alone, but when accompanied by another finding of blood pressure measuring 180/110 mm Hg, the level of importance of the first finding increases. Questions arise as to whether the patient’s hypertension is being managed appropriately or whether the patient is even taking the prescribed medication regularly. Obviously, further questioning of the patient is in order, generating even more findings to evaluate for significance. The process of differentiating significant from insignificant findings can be challenging for dental students and recent graduates. For example, a student may believe a dark spot on the occlusal surface of a tooth to be significant, whereas a faculty member might discard the finding as simply stained fissure, not requiring treatment. Thankfully, this differentiation and selection process becomes easier as the clinician gains experience from examining and treating more and more patients.

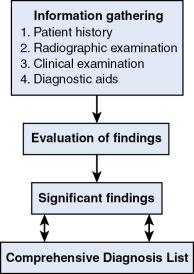

The process of discovering significant findings leads to a list of diagnoses and patient problems, and a comprehensive patient diagnosis, that ultimately forms the basis for creating a treatment plan ( Figure 1-2 ). Diagnoses are precise terms that identify a particular disease or problem from signs or symptoms. Examples include diabetes, caries, periodontitis, malocclusion. Problems can defy a precise diagnosis but are important issues to be addressed when planning treatment. Examples include pain, swelling, difficulty chewing, or dissatisfaction with appearance. Additional examples of common diagnoses and problems are discussed in Chapter 2 .

Experienced practitioners may not always evaluate patients in a linear, sequential fashion. Instead, they move back and forth between discovering findings, evaluating for significance, and making a diagnosis, and they may begin to think about treatment options before gathering all the data. Despite this normal process, the novice practitioner (and even the experienced one) is highly advised against proposing treatment recommendations to patients before creating and analyzing the entire patient database. Typically, the patient initiates the discussion during the examination process. For example, examination of a sensitive tooth may elicit a query from the patient as to whether it can be saved and at what cost. Saying “yes” and “in two appointments” may prove embarrassing when subsequent radiographs reveal extensive decay and the need to extract the tooth. To prevent such errors, the inquisitive patient should be gently reminded that the examination is not yet complete and that, as more information is gathered, it will be possible to answer questions more completely.

Gathering and recording information about the patient often requires more time and attention than any other aspect of treatment planning. To prevent missing important findings, the dentist should gather data in an organized, systematic manner. Each practitioner must develop a consistent and standardized method for gathering historical information about the patient, obtaining radiographs, and performing the clinical examination. It is essential that any data gathered be both complete and accurate. If deficiencies occur in either completeness or accuracy, the validity of the final treatment plan may be suspect.

The sheer number of findings that arise when evaluating a patient with many dental problems or a complicated health history can overwhelm the beginning practitioner. Staying focused on each stage of information gathering and being careful to record information in an organized and systematic fashion for later analysis help to prevent confusion. This section discusses the four major categories of information required to begin developing a treatment plan: the patient history, clinical examination, radiographic examination, and other diagnostic aids.

Overview of the diagnostic process

The diagnostic process is begun by gathering information about the patient and creating a patient database that will serve as the basis for all future patient care decisions. Although the components of each patient’s database vary, each includes pieces of relatively standard information, or findings, that come from asking questions, reviewing information on forms, observing and examining structures, performing diagnostic tests, and consulting with physicians and other dentists.

Findings fall into several categories. Signs are findings discovered by the dentist during an examination. For instance, the practitioner may observe that a patient has swollen ankles and difficulty in breathing when reclined, signs suggestive of congestive heart failure. Findings verbally revealed by the patients themselves, usually because they are causing problems, are referred to as symptoms . Patients may report such common symptoms as pain, swelling, broken teeth, loose teeth, bleeding gums, or esthetic concerns. When a symptom becomes the motivating factor for a patient to seek dental treatment, it is referred to as the chief complaint or chief concern . Patients who are new to a practice or presenting for emergency dental care often have one or more chief concerns ( Figure 1-1 ).

The clinician must evaluate findings individually and in conjunction with other findings to determine whether the finding is significant. For example, the finding that a patient is being treated for hypertension may be not be significant alone, but when accompanied by another finding of blood pressure measuring 180/110 mm Hg, the level of importance of the first finding increases. Questions arise as to whether the patient’s hypertension is being managed appropriately or whether the patient is even taking the prescribed medication regularly. Obviously, further questioning of the patient is in order, generating even more findings to evaluate for significance. The process of differentiating significant from insignificant findings can be challenging for dental students and recent graduates. For example, a student may believe a dark spot on the occlusal surface of a tooth to be significant, whereas a faculty member might discard the finding as simply stained fissure, not requiring treatment. Thankfully, this differentiation and selection process becomes easier as the clinician gains experience from examining and treating more and more patients.

The process of discovering significant findings leads to a list of diagnoses and patient problems, and a comprehensive patient diagnosis, that ultimately forms the basis for creating a treatment plan ( Figure 1-2 ). Diagnoses are precise terms that identify a particular disease or problem from signs or symptoms. Examples include diabetes, caries, periodontitis, malocclusion. Problems can defy a precise diagnosis but are important issues to be addressed when planning treatment. Examples include pain, swelling, difficulty chewing, or dissatisfaction with appearance. Additional examples of common diagnoses and problems are discussed in Chapter 2 .

Experienced practitioners may not always evaluate patients in a linear, sequential fashion. Instead, they move back and forth between discovering findings, evaluating for significance, and making a diagnosis, and they may begin to think about treatment options before gathering all the data. Despite this normal process, the novice practitioner (and even the experienced one) is highly advised against proposing treatment recommendations to patients before creating and analyzing the entire patient database. Typically, the patient initiates the discussion during the examination process. For example, examination of a sensitive tooth may elicit a query from the patient as to whether it can be saved and at what cost. Saying “yes” and “in two appointments” may prove embarrassing when subsequent radiographs reveal extensive decay and the need to extract the tooth. To prevent such errors, the inquisitive patient should be gently reminded that the examination is not yet complete and that, as more information is gathered, it will be possible to answer questions more completely.

Gathering and recording information about the patient often requires more time and attention than any other aspect of treatment planning. To prevent missing important findings, the dentist should gather data in an organized, systematic manner. Each practitioner must develop a consistent and standardized method for gathering historical information about the patient, obtaining radiographs, and performing the clinical examination. It is essential that any data gathered be both complete and accurate. If deficiencies occur in either completeness or accuracy, the validity of the final treatment plan may be suspect.

The sheer number of findings that arise when evaluating a patient with many dental problems or a complicated health history can overwhelm the beginning practitioner. Staying focused on each stage of information gathering and being careful to record information in an organized and systematic fashion for later analysis help to prevent confusion. This section discusses the four major categories of information required to begin developing a treatment plan: the patient history, clinical examination, radiographic examination, and other diagnostic aids.

Information gathering

Patient history

The distinguished Canadian physician Sir William Osler wrote, “Never treat a stranger.” His words underscore the need for a thorough patient history; experienced dentists learn everything they can about their patients before beginning treatment. Obtaining a complete and accurate patient history is part of the art of being a doctor. It takes considerable practice and self-study to become a talented investigator. No set amount of historical information is required for each patient. The volume of information collected and the complexity of the data collection process naturally depend on the severity of the patient’s problems. As more information comes to light, additional diagnostic techniques may need to be used.

In dental offices, persons other than the dentist have access to patient information. The entire office staff should be aware of the confidential nature of patient information and cautioned about discussing any patient’s general or oral health history other than for treatment purposes. The author is reminded of an example of a lapse in confidentiality. When updating the health history, a staff member learned that a patient had recently become pregnant. Later in the day, the patient’s mother was in the office, and another staff member congratulated her on her daughter’s pregnancy. At first the mother was elated, but later was hurt that her daughter had not told her herself. The incident provided an uncomfortable reminder of the importance of keeping patient information confidential both inside and outside the office.

In the United States, the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996, HIPAA, requires practitioners and healthcare organizations to prevent unnecessary use and release of protected health information (PHI) . Patient PHI includes medical findings, diagnoses and treatment notes, and any demographic data that could identify the patient, such as an address, phone number, or personal identification number. HIPAA permits the use of a patient’s PHI for treatment purposes, obtaining payment for services, and other organizational requirements, such as quality assurance activities or assisting legal authorities. Patients must be given, and sign, an acknowledgment that they have received information about how the practitioner or organization will use the PHI and whom they can contact if they believe their health information has been inappropriately used or released. Under HIPAA, the patient also has the right to inspect, and even amend, his or her medical records.

Techniques for obtaining a patient history

The two primary methods for obtaining the patient history are (1) questionnaires and forms and (2) patient interviews. A secondary method involves requesting information from another healthcare practitioner.

Questionnaires and forms.

The use of questionnaires and forms during the examination process offers several advantages. Questionnaires save time, do not require any special skills to administer, and provide a standardized method for obtaining information from a variety of patients. Many types of forms are available commercially, or the practitioner can create his or her own.

Unfortunately, using a form to gather information has several disadvantages. The dentist only gets answers to the questions asked on the form, and important findings may be missed. The severity of a condition may not be reflected in a simple positive response. Patients may misinterpret questions, resulting in incorrect answers. It may be necessary to have the forms printed in other languages to facilitate information gathering. The more comprehensive the questionnaire is, the longer it must be, which can be frustrating to patients. Many dental clinics have implemented electronic health records (EHR), and patients may now enter their health information directly into electronic forms. One advantage of using this method is that the initial questionnaire can be brief, with the patient being prompted for more information if there is a positive response to a higher-level question. This individualized approach to delving into the positive responses would be difficult to duplicate efficiently with a paper form. Finally, with a questionnaire or form, patients can more easily falsify or fail to completely reveal important information than when confronted directly in an interview.

Patient interviews.

A major advantage to interviewing patients is that the practitioner can tailor questions to the individual patient. The patient interview serves a problem-solving function and develops quite differently from a personal conversation. There is a level of formality to the discussion, which centers on the patient’s health and oral care needs, problems, and desires. To obtain accurate information and avoid influencing the responses, the dentist must be a systematic and unbiased information gatherer and must have excellent communication skills. The clinician must adapt these skills to interact with patients from varying cultural, gender, and socioeconomic backgrounds. Being a good listener is key to facilitating information flow from the patient. The desired outcome of the interviewing process is the development of a good rapport with the patient by establishing a cooperative and harmonious interaction.

If the interviewer does not speak the patient’s language, it may be necessary to have translation services available. A sign language translator may be also required if the patient is hearing impaired. Older patients may require more time for interviewing, particularly if their health histories are complex.

The dentist can ask two general types of questions when interviewing: open and closed. Open questions cannot be answered with a simple response, such as “yes” or “no.” Instead, open questions get the patient involved and generate reflection by asking for opinions, past experiences, feelings, or desires. Open questions usually begin with “what” or “how” and should avoid leading the patient to a specific answer.

Examples:

- •

How may I help you?

- •

What do you think is your biggest dental problem?

- •

Tell me about your past dental care.

- •

Tell me more about your heart problems.

Closed questions, on the other hand, are usually simple to answer with one or two words. They permit specific facts to be obtained or clarified but do not give insight into patient beliefs, attitudes, or feelings.

Examples:

- •

Do any of your teeth hurt?

- •

Which tooth is sensitive to cold?

- •

How long has it been since your teeth were last examined?

- •

Do you have a heart problem?

In general, the examiner should use open questions when beginning to inquire about a problem. Later, closed questions can be asked to obtain answers to specific questions. The skilled clinician knows when to use each type of question during the interview. Examples are presented in the following sections. The In Clinical Practice box features tips on how to be an effective interviewer .

Principles for effective interviewing

- •

Eye contact is important, so position the dental chair upright and sit facing the patient. Raise or lower the operator’s stool so that your eyes are at the same level as the patient’s.

- •

Use open-ended questions when seeking further information about positive responses to items on the health questionnaire.

- •

If the patient is hesitant or doesn’t answer, explain why you are asking the question.

- •

Be an objective, unbiased interviewer. Avoid adding personal feelings. The primary goals during the interview are to accumulate and assess the facts, not to influence them.

- •

Be an attentive, active listener. The “golden rule” of interviewing is to listen more than speak.

- •

Use verbal facilitators like “yes” and “uh huh” to encourage patients to share information.

- •

Be aware of the patient’s nonverbal communication, such as crossing arms or legs or avoiding making eye contact.

- •

At the conclusion of the interview, summarize what you’ve learned from the patient to confirm accuracy.

- •

See Video 1-1 Effective and Ineffective Interviewing on Evolve.

See Video 1-1 Effective and Ineffective Interviewing on Evolve.

Components of a patient history

Demographic data.

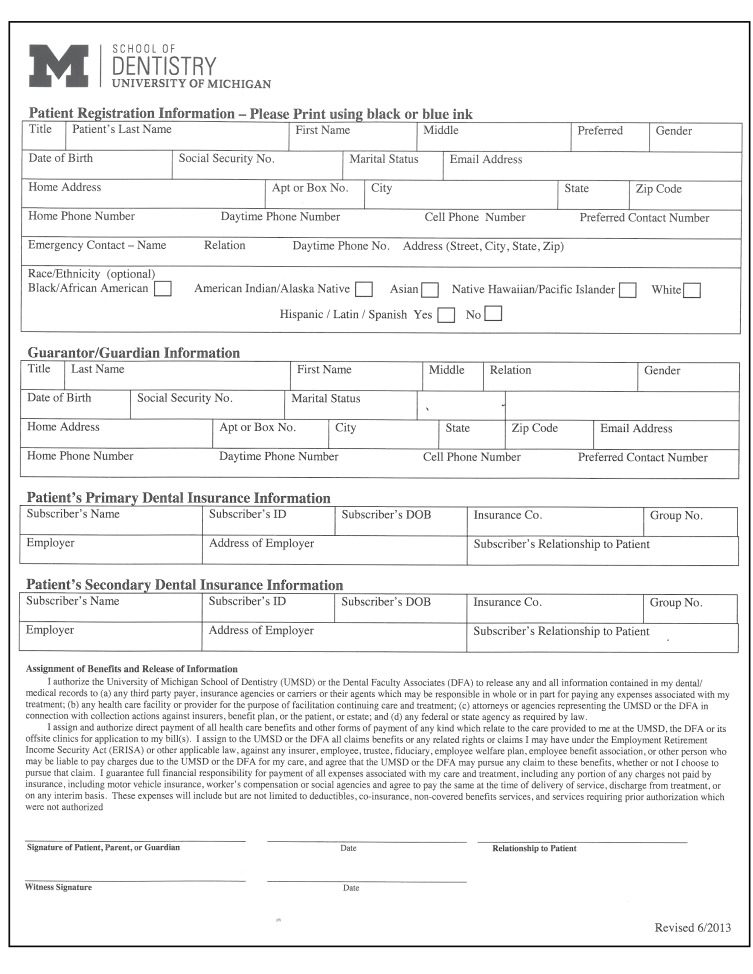

Demographic data includes basic information, such as the patient’s name, address, phone number, physician’s name and phone, third party (insurance) information, national identification information, and so on. Demographic data, like any other historical information, must be accurate, complete, and current. Errors in recording insurance information, such as an incorrect policy number or failure to clarify who is responsible for payment, can be costly to a dental practice.

Useful additional information includes work, mobile, and evening telephone numbers, and seasonal and electronic mail addresses. The patient reports most of this information on demographic questionnaires and forms at the first visit ( Figure 1-3 ). The office staff may also interview the patient if additional information is required or if information requires updating. Although commercial forms can be used to record and organize demographic information, many practices have designed their own. Dental practices that use an electronic health record instead of a paper record may scan paper forms or have the patient enter information into a computer or hand held device that is linked directly to the clinic information system.

Chief concern or complaint and history.

The chief complaint or chief concern is the primary reason, or reasons, that the patient has presented for treatment. For most patients, the chief complaint is usually a symptom or a request. Any complaints are best obtained by asking the patient an open-ended question, such as, “What brought you to see me today?” or “Is there anything in particular you are hoping I can do for you?” This is more effective than limiting the patient’s response by asking a closed question, such as: “Is anything bothering you right now?” or “Has it been a long time since you’ve seen a dentist?” Record chief complaints in quotes to signify that the patient’s own words are used. Careful attention to the chief complaint should alert the practitioner to important diagnoses and provide an appreciation for the patient’s perception of his or her problems, including level of knowledge about dentistry.

The history of present illness (HPI) is the history of the chief complaint, which the patient usually supplies with a little prompting. When possible, the dentist should keep the questioning open, although specific (closed) questions help clarify details.

Example 1:

-

Chief complaint

-

“My tooth hurts.” (a symptom)

-

-

HPI: The patient has had a dull ache in the lower right quadrant that has been increasing in intensity for the past 4 days. The pain is worse with hot stimuli and chewing and is not relieved by aspirin.

Example 2:

-

Chief complaint

-

“I lost a filling and need my teeth checked.” (a symptom and a request)

-

-

HPI: The patient lost a restoration from an upper right molar 2 days ago. The tooth is asymptomatic. Her last dental examination and prophylaxis were 2 years ago.

Resolving the patient’s chief complaint as soon as possible represents a “golden rule” of treatment planning. When a new patient presents in pain, the dentist may need to suspend the comprehensive examination process and instead focus on the specific problem, make a diagnosis and, quite possibly, begin treatment.

At times, the chief complaint may be very general, such as, “I need to chew better,” or “I don’t like the appearance of my teeth.” In such instances, the practitioner must carefully dissect the issues of concern to the patient. Often, what initially appears to be the problem may be a more complex issue that will be difficult to manage until later in the treatment plan. During the course of treatment, the dentist should advise the patient as to what progress is being made toward resolving the initial chief complaint.

General health history.

The dentist must obtain a health history from each patient and regularly update this information in the record. A comprehensive health history contains a review of all of the patient’s past and present physical illnesses and psychiatric disorders. Information about a patient’s health history can prevent or help manage an emergency. Some systemic diseases may affect the oral cavity and the patient’s response to dental treatment, including delaying healing or increasing the chance for infection. Conversely, some oral diseases can affect the patient’s general health. Because many patients see their dentist more frequently than they see their physician, the dentist should use the patient’s general health history and physical examination to screen for significant systemic diseases, such as hypertension and diabetes.

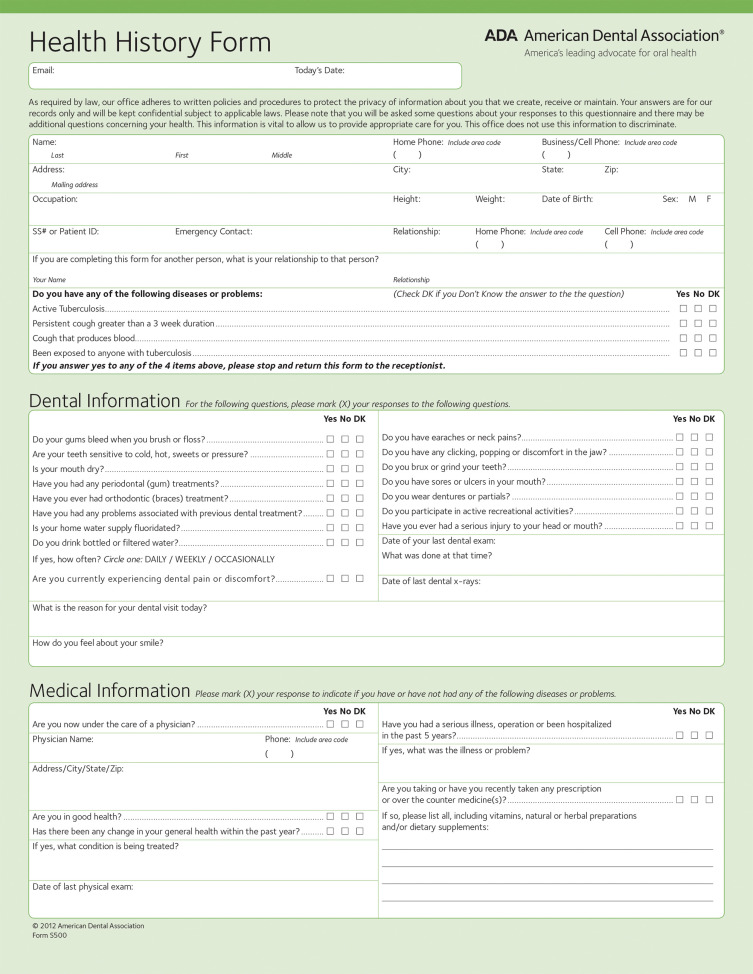

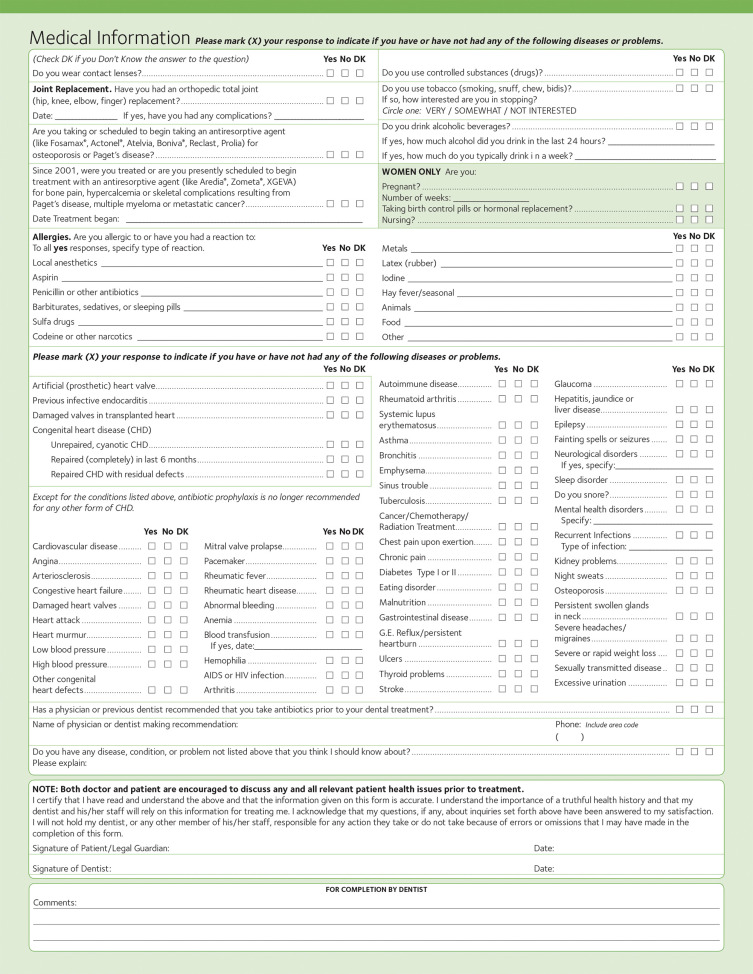

Most dental practices screen for potential health problems by asking all new patients to complete a health questionnaire ( Figure 1-4 ). When reviewing the health questionnaire, the dentist must look for conditions that may affect head and neck findings, treatment, patient management, or treatment outcomes. Interviewing the patient, first with open-ended questions about the problem and later with closed questions, usually clarifies positive responses to the questionnaire. Although it is beyond the scope of this book to present all the systemic conditions that can affect dental treatment, several are discussed in Chapter 7 , including guidelines for consulting with the patient’s physician when the dentist has detected significant findings.

Whether using a preprinted questionnaire or an interview technique, the general health history should include a review of systems. The information gained through the review of systems enables the dentist (1) to recognize significant health problems that may affect dental treatment and (2) to elicit information suggestive of new health problems that have been previously unrecognized, undiagnosed, or untreated. Commonly reviewed systems and examples of some significant findings are shown in Table 1-1 .

| System | Examples of significant findings for dentists |

|---|---|

| Constitutional symptoms (e.g., fever, weight loss) | Unexplained weight loss, fatigue and malaise, fever, recent trauma |

| Eyes | Vision loss |

| Ears, nose, mouth, and throat | Hearing loss, sinus problems |

| Cardiovascular | Hypertension, chest pain, shortness of breath |

| Respiratory | Cough, shortness of breath, wheezing |

| Gastrointestinal | Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), unhealthy diet, food avoidance, and allergies |

| Genitourinary | Pregnancy |

| Musculoskeletal | Arthritis and joint pain, inability to sit/recline |

| Integumentary (skin and/or breast) | Skin lesions |

| Neurological | Headache, seizures, fainting |

| Psychiatric | Depression, anxiety, bipolar disorders, side effects of medications |

| Endocrine | Diabetes, thyroid problems |

| Hematologic/lymphatic | Anemia, coagulation problems, liver diseases |

| Allergic/immunologic | Medication allergies, seasonal allergies |

Medication history.

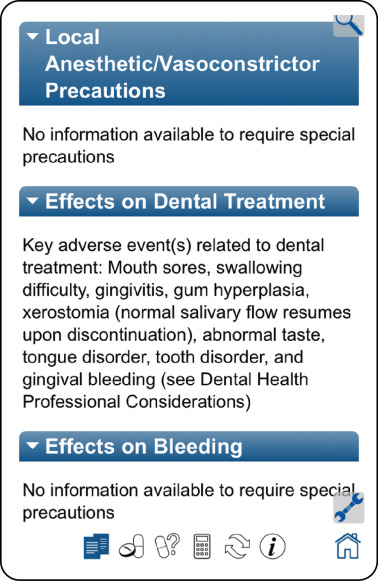

Including both prescription and nonprescription medications in the medication history also provides valuable insight into the patient’s overall health. Any over-the-counter medications, herbal remedies, vitamins, or nutritional supplements used also should be included. The medication history can corroborate findings from the health history or may suggest new diseases or conditions that need further investigation. Some medications are, in themselves, cause for limiting, delaying, or modifying dental treatment. The dentist may consult one of several reference sources to help determine the indications and potential problems that may arise from the use of various drugs. Several references, available on electronic media or on the Internet, provide rapid access to information ( Figure 1-5 ).

Personal history.

The patient’s social, emotional, and behavioral history represents one of the most important and challenging areas to investigate. The patient’s occupation, habits, financial resources, and general lifestyle can significantly influence attitudes about dentistry. It is important to investigate the patient’s attitudes about the profession, including priorities, expectations, and motivations for seeking treatment. The personal history is also a prime source of information about the patient’s financial status, time availability for treatment, and mode of transportation to dental visits—any or all of which may have a bearing on how dental treatment is planned or executed. Much of the personal history will overlap with the oral health history, especially concerns relating to fear of dental treatment (covered in depth in Chapter 14 ) and concerns about the cost of treatment (discussed in Chapter 18 ).

The personal history also includes information about the patient’s nutrition and dietary habits, with the primary goal of determining the level of fermentable carbohydrates consumed. Frequently used screening questions include

-

“What do you drink during the day?”

-

“What do you eat for meals and for snacks?”

-

“Where is there sugar in your diet?”

The health questionnaire can be used to evaluate the personal history for information about habits such as smoking, alcohol, and drug use, and the clinician should quantify the extent of use. Often, however, these questions are best pursued verbally, during the patient interview. For cigarette smokers, the number of packs of cigarettes is multiplied by the number of years the patient has smoked ( 1 ⁄ 2 pack a day for 10 years is a 5 pack-year smoking habit). A patient’s behavior or medication profile may suggest the presence of some type of psychological disorder, a topic discussed further in Chapter 15 .

Oral health history.

The oral health history incorporates such areas as the date of last dental examination, frequency of dental visits, types of treatment received, and history of any problems that have emerged when receiving dental care. Common problems include syncope (fainting), general anxiety, and reactions to drugs used in dentistry. Patients should also be questioned about their oral hygiene practices. Experienced dentists spend whatever time is necessary to investigate the oral health history of the patient because of the strong influence it can have on future treatment.

While obtaining the oral health history, the dentist should first determine the general nature of the patient’s past care. Has the patient seen a dentist regularly or been treated only on an episodic basis? What kind of oral healthcare did the patient receive as a child? The frequency of oral healthcare can be an important predictor of how effectively the patient will comply with new treatment recommendations. If the patient has visited the dentist regularly, what types of treatment were provided? Was the patient satisfied with the treatment received? Did the dentist do anything in particular to make treatment more comfortable? It also is important to establish whether the patient has had any specialty treatment, such as orthodontic, endodontic, or periodontal care, in the event additional such treatment is required in the future.

Investigation into the patient’s dental history supplements the clinical examination, during which new findings may be identified. The dentist should establish the explanation for any missing teeth, including when they were removed. Knowing the age of suspect restorations may yield important perspectives on the quality of previous work, how well previous treatment has held up, the patient’s oral hygiene, and the prognosis for new work. The age of tooth replacements may also have a bearing on whether the patient’s dental insurance will cover any necessary replacement.

Clinical examination

Developing an accurate and comprehensive treatment plan depends on a thorough analysis of all general and oral health conditions that exist when the patient presents for evaluation. A comprehensive clinical examination involves assembling significant findings from the following five areas:

- •

Physical examination

- •

Intraoral and extraoral soft tissue examination

- •

Periodontal examination

- •

Examination of the teeth

- •

Radiographic examination

Physical examination

The dentist has several tools that can be used to evaluate the patient’s overall physical condition. Obtaining the patient’s blood pressure and pulse rate represents one objective method. A more subjective, but equally valuable, approach involves simply evaluating the patient’s appearance, looking both at general physical attributes and, more specifically, at the head and neck area. During this process, the clinician is searching for variations from normal that are not being managed by a physician and may have significance in a dental setting.

Unlike the physician, who examines many areas of the body for signs of disease, the dentist in general practice usually performs only a limited overall physical examination that includes only evaluation of

- •

Patient posture and gait

- •

Exposed skin surfaces

- •

Vital signs

- •

Cognition and mental acuity

- •

Speech and ability to communicate

With careful observation and findings from the health history, the dentist can detect many signs of systemic diseases that could have treatment implications and may suggest referral to a physician. For example, a patient who has difficulty walking may be afflicted with osteoarthritis or have a neurologic problem, such as Parkinson’s disease or the after effects of a stroke. The appearance of the skin, hair, and eyes may suggest such diseases as anemia, hypothyroidism, or hepatitis.

Vital signs.

Measuring vital signs provides an easy and objective measurement for physical evaluation. Blood pressure and pulse rate measurements should be obtained at every new patient examination, and at subsequent periodic examinations. With the advent of accurate electronic blood pressure measuring devices, measuring blood pressure and pulse rate has become a relatively simple process. Many clinicians routinely take the blood pressure at every visit in which a local anesthetic or sedative medication will be administered. The vital signs should also be taken at the beginning of all visits for patients under treatment for high blood pressure, thyroid disease, or cardiac disease.

Blood pressure measurements can vary considerably between individuals. Target blood pressure values for adults are listed in Table 1-2

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses