-

Outline

-

Definition of Evidence-Based Dentistry, Risk Assessment, Prognosis, and Treatment Outcomes

-

Professional Variability and Disagreement in Treatment Planning

![]()

Health promotion and disease prevention have received increasing emphasis in the health sciences, and have become a particular focus in dentistry. Programs and practices put into place to promote these goals must be based on appropriate evidence if they are to have any reasonable likelihood of success. The emergence of evidence-based dentistry (EBD) has significant implications for the dental treatment planning process for individual patients as well as for the design of parameters that will support decision making in the delivery of dental healthcare. Treatment planning with a focus on health promotion and disease prevention must include a careful assessment of both the patient’s disease risk and potential treatment outcomes. Analyses of both disease prognosis (with or without treatment) and treatment prognosis will also be integral to this process.

The intent of this chapter is to frame the context for decision making in dentistry. A perspective on how dental treatment planning decisions have typically been made will be included, as will a discussion of the limitations of that process. Recognizing that there is often inadequate information at the dentist and patient level on which to base treatment decisions, there is a call for meaningful clinical investigations to support clinical decision making. The concepts of risk assessment, outcomes assessment, and prognosis determination will be defined and described, and their relevance to dental treatment planning will be discussed. Findings from research in these areas can be expected to improve future dental treatment planning and to have a positive effect on the oral health of patients. In the meantime, the concepts themselves offer the practicing dentist a systematic approach to organizing the process of assessing clinical problems and possible solutions. In addition, these concepts provide a useful framework for presenting and discussing treatment options with the patient.

In summary, the purposes of this chapter are to discuss the kinds of information dentists need to help patients make informed decisions and to review some related areas of dentistry in which progress in this area has been made. We will also provide a template for dentist and patient decision making as more information becomes available. This chapter provides the foundation for the detailed process of treatment planning, which is delineated in Chapter 4 and then applied repeatedly throughout the subsequent chapters of this textbook.

Definition of evidence-based dentistry, risk assessment, prognosis, and treatment outcomes

Evidence-based dentistry

The concept of evidence-based decision making is well established in all of the health sciences and is a core element in contemporary dental treatment planning. It has been defined as “the integration of best research evidence with clinical expertise and patient values.” EBD requires a careful assessment of clinically relevant scientific evidence in light of:

- •

the patient’s oral and general health

- •

the dentist’s clinical expertise, and

- •

the patient’s treatment needs and preferences

EBD is based on scientific principles and treatment regimens that have been tried, tested, and proven worthy by accurate, substantiated, and reproducible studies. Ideally, any treatment method, whether in dentistry or medicine, should be supported by current, controlled, blinded, prospective longitudinal studies. Unfortunately, for many, if not most, clinical treatments, this type of evidence is not yet available.

Where valid current applicable research exists, it can affirm or disprove the efficacy of various dental treatments and thereby provide compelling guidance to the patient and practitioner on the “treat versus not treat” question. In other situations, when several different viable alternatives are being weighed, it can provide the basis for moving to a specific decision. The strength of the evidence needs to be considered as it is factored into the decision making. The stronger the evidence, the more seriously it should be weighed. Conversely, the weaker the evidence, the less likely that it will drive or influence decision making.

Although the use of EBD has become an integral component of the treatment planning process, other factors must also be considered. The application of dental research and published studies must be tempered by an understanding of the limitations of these resources:

- •

Many treatments remain to be analyzed, especially in the long term

- •

There is insufficient evidence to determine the viability of many treatments

- •

Many treatments do not have strong evidentiary support, but may still be viable (especially compared with other, even less attractive, alternatives)

- •

The relevant studies may not be applicable to individual patient circumstances (e.g., general health; immune response; condition of the oral cavity, tooth, tooth surface; disease risk)

- •

Most studies do not address patient factors (e.g., patient’s prior experience) as described throughout this text

- •

Most outcomes studies look exclusively at treatment efficacy and rarely correlate that efficacy with patient preferences and desires

How then does the dentist make decisions and recommend treatment when the evidence is not strong? To make a treatment planning decision, the dentist and patient may need to rely more heavily on other professional (what has your experience revealed?), or patient driven (what has been the patient’s previous experience with a similar procedure?) parameters. The range of treatment options may have to be expanded to accommodate other treatment approaches that may be similarly unproven, but that may be viable in this situation. In any case, it is incumbent on the dentist to ensure that the patient is informed about the limits of our evidence-based knowledge. In the end, it is essential for the patient to be an informed and active partner in the decision making. When there is a limited evidence base for treatment planning, the dentist has an obligation for wider, not narrower, disclosure in achieving informed consent.

Risk assessment

Risk assessment is the determination of the likelihood of a patient’s acquiring a specific disease or condition. Not all patients are equally likely to develop a particular disease. Some patients, because of heredity, environment, diet, personal habits, systemic health, medications, or other factors, are more likely than others to develop and/or continue to be afflicted by certain conditions. Those patients who have predisposing conditions or who engage in behaviors known to promote a particular disease are described as at increased risk . This differs from the epidemiologic definition of “at risk.” In epidemiology, anyone who could potentially develop the condition is “at risk”; and individuals who could not develop the condition are “not at risk.” Edentulous patients, for example, are not at risk for caries development, but everyone who has at least one natural tooth is at risk for caries development. This distinction is important in determining the denominator for incidence and prevalence estimates. In both realms, however, clinical and epidemiologic, someone who has a strong probability of developing the condition is “at high risk.”

Prognosis

A prognosis is a prediction, based on present circumstances, of the patient’s future condition. It is usually expressed in such general terms as “excellent,” “good,” “favorable,” “unfavorable,” “fair,” “poor,” “questionable,” or “hopeless.” A prognosis can be made for an individual tooth, for various oral conditions (e.g., oral cancer, periodontal disease), for the various treatment disciplines, or for the patient’s overall prognosis. An essential difference between risk assessment and prognosis is that the former focuses on the propensity to develop a disease; the latter predicts the future course of the disease (progression or regression), both with and without treatment.

For a specific patient, varying prognoses can be determined for multiple disease processes, as well as for recommended treatments. Although the prognosis for the disease and the treatment may be related, they are not necessarily the same. For example, a patient with moderate periodontitis may have a good prognosis for control of the disease, but a poor or questionable prognosis for a long span, fixed partial denture that is anchored on the involved teeth. Conversely, a patient with severe periodontitis may be described as having a poor prognosis for control of the disease, but a good prognosis for a related treatment, an implant-retained removable partial denture.

Treatment outcomes

Outcomes, in the specific context of this discussion, are the specific, tangible results of treatment. The results that a patient and practitioner anticipate receiving as a result of a course of treatment are outcomes expectations. An outcome expectation will be closely linked to both risk assessment and prognosis determination. For example, if the patient remains at increased risk for new caries and the prognosis for control of the caries is poor, then it follows that the outcomes of treatment can be expected to be unfavorable. But the two differ fundamentally in that although prognosis always looks to the patient’s future condition, outcomes assessment looks at past performance (both individual and group) and, even when the outcomes measures are used to estimate future success, those expectations are still predictions based on past performance.

Expected outcomes are usually expressed in quantifiable terms based on sound clinical research, such as the average life expectancy of a restoration. Although outcome measures for the complete range of dental treatment procedures are not yet available, some meaningful work has been published, and examples of selected findings are discussed later in this chapter.

Definition of evidence-based dentistry, risk assessment, prognosis, and treatment outcomes

Evidence-based dentistry

The concept of evidence-based decision making is well established in all of the health sciences and is a core element in contemporary dental treatment planning. It has been defined as “the integration of best research evidence with clinical expertise and patient values.” EBD requires a careful assessment of clinically relevant scientific evidence in light of:

- •

the patient’s oral and general health

- •

the dentist’s clinical expertise, and

- •

the patient’s treatment needs and preferences

EBD is based on scientific principles and treatment regimens that have been tried, tested, and proven worthy by accurate, substantiated, and reproducible studies. Ideally, any treatment method, whether in dentistry or medicine, should be supported by current, controlled, blinded, prospective longitudinal studies. Unfortunately, for many, if not most, clinical treatments, this type of evidence is not yet available.

Where valid current applicable research exists, it can affirm or disprove the efficacy of various dental treatments and thereby provide compelling guidance to the patient and practitioner on the “treat versus not treat” question. In other situations, when several different viable alternatives are being weighed, it can provide the basis for moving to a specific decision. The strength of the evidence needs to be considered as it is factored into the decision making. The stronger the evidence, the more seriously it should be weighed. Conversely, the weaker the evidence, the less likely that it will drive or influence decision making.

Although the use of EBD has become an integral component of the treatment planning process, other factors must also be considered. The application of dental research and published studies must be tempered by an understanding of the limitations of these resources:

- •

Many treatments remain to be analyzed, especially in the long term

- •

There is insufficient evidence to determine the viability of many treatments

- •

Many treatments do not have strong evidentiary support, but may still be viable (especially compared with other, even less attractive, alternatives)

- •

The relevant studies may not be applicable to individual patient circumstances (e.g., general health; immune response; condition of the oral cavity, tooth, tooth surface; disease risk)

- •

Most studies do not address patient factors (e.g., patient’s prior experience) as described throughout this text

- •

Most outcomes studies look exclusively at treatment efficacy and rarely correlate that efficacy with patient preferences and desires

How then does the dentist make decisions and recommend treatment when the evidence is not strong? To make a treatment planning decision, the dentist and patient may need to rely more heavily on other professional (what has your experience revealed?), or patient driven (what has been the patient’s previous experience with a similar procedure?) parameters. The range of treatment options may have to be expanded to accommodate other treatment approaches that may be similarly unproven, but that may be viable in this situation. In any case, it is incumbent on the dentist to ensure that the patient is informed about the limits of our evidence-based knowledge. In the end, it is essential for the patient to be an informed and active partner in the decision making. When there is a limited evidence base for treatment planning, the dentist has an obligation for wider, not narrower, disclosure in achieving informed consent.

Risk assessment

Risk assessment is the determination of the likelihood of a patient’s acquiring a specific disease or condition. Not all patients are equally likely to develop a particular disease. Some patients, because of heredity, environment, diet, personal habits, systemic health, medications, or other factors, are more likely than others to develop and/or continue to be afflicted by certain conditions. Those patients who have predisposing conditions or who engage in behaviors known to promote a particular disease are described as at increased risk . This differs from the epidemiologic definition of “at risk.” In epidemiology, anyone who could potentially develop the condition is “at risk”; and individuals who could not develop the condition are “not at risk.” Edentulous patients, for example, are not at risk for caries development, but everyone who has at least one natural tooth is at risk for caries development. This distinction is important in determining the denominator for incidence and prevalence estimates. In both realms, however, clinical and epidemiologic, someone who has a strong probability of developing the condition is “at high risk.”

Prognosis

A prognosis is a prediction, based on present circumstances, of the patient’s future condition. It is usually expressed in such general terms as “excellent,” “good,” “favorable,” “unfavorable,” “fair,” “poor,” “questionable,” or “hopeless.” A prognosis can be made for an individual tooth, for various oral conditions (e.g., oral cancer, periodontal disease), for the various treatment disciplines, or for the patient’s overall prognosis. An essential difference between risk assessment and prognosis is that the former focuses on the propensity to develop a disease; the latter predicts the future course of the disease (progression or regression), both with and without treatment.

For a specific patient, varying prognoses can be determined for multiple disease processes, as well as for recommended treatments. Although the prognosis for the disease and the treatment may be related, they are not necessarily the same. For example, a patient with moderate periodontitis may have a good prognosis for control of the disease, but a poor or questionable prognosis for a long span, fixed partial denture that is anchored on the involved teeth. Conversely, a patient with severe periodontitis may be described as having a poor prognosis for control of the disease, but a good prognosis for a related treatment, an implant-retained removable partial denture.

Treatment outcomes

Outcomes, in the specific context of this discussion, are the specific, tangible results of treatment. The results that a patient and practitioner anticipate receiving as a result of a course of treatment are outcomes expectations. An outcome expectation will be closely linked to both risk assessment and prognosis determination. For example, if the patient remains at increased risk for new caries and the prognosis for control of the caries is poor, then it follows that the outcomes of treatment can be expected to be unfavorable. But the two differ fundamentally in that although prognosis always looks to the patient’s future condition, outcomes assessment looks at past performance (both individual and group) and, even when the outcomes measures are used to estimate future success, those expectations are still predictions based on past performance.

Expected outcomes are usually expressed in quantifiable terms based on sound clinical research, such as the average life expectancy of a restoration. Although outcome measures for the complete range of dental treatment procedures are not yet available, some meaningful work has been published, and examples of selected findings are discussed later in this chapter.

Traditional model for dental treatment planning

Traditionally, dental students have been taught that before initiating anything other than emergency/urgent dental treatment, every patient must have a comprehensive “ideal” treatment plan that is based on a stepwise process: first, a thorough evaluation and examination of the patient is conducted; next, diagnoses are made and/or a problem list is developed; and finally, a series of treatments is constructed and presented by the dentist and agreed to by the patient. This model has stood the test of time and has significant merit. Its rationale and virtues are discussed at length in other chapters, and it is the basis for the treatment planning process described throughout this text.

In practice, however, many dentists often do not follow the stepwise model when treatment planning for their patients. Often, an individual tooth condition or other oral problem is evaluated and the dentist makes an immediate recommendation to the patient about what should be done to resolve the problem. This may be an expedient way for the practitioner to gain a modicum of consent from the patient to begin treatment. However, a clearly articulated diagnosis and prognosis often are not made, and even in those cases in which the dentist makes a mental judgment about the rationale for treatment, the diagnosis may not be explicitly stated to the patient. Thus the patient may remain relatively uninformed about the nature of the problem and the rationale for a particular treatment.

It is also unlikely in this situation that the patient will be presented with more than one option for treatment. Even when the patient is given options, the choices are stated in a perfunctory way, and the patient is given minimal information from which to make a well-reasoned, thoughtful decision. Given the time pressures of a daily dental practice, these omissions can evolve to become the routine rather than the exception. The patient who remains relatively uninformed about diagnoses and treatment options, however, is ill prepared to provide meaningful informed consent for treatment. This can be both unwise and hazardous from a risk management perspective (see Chapter 6 ). The need to achieve fully informed consent is a central theme of this text.

Another concern associated with focusing on individual tooth problems and failing to follow a stepwise comprehensive approach to treatment planning is that the dentist does not have the opportunity to factor in where that particular problem fits in the overall context of the patient’s oral condition. When used to its fullest, the stepwise model helps ensure that the dentist considers—and the patient is informed about—all diagnoses and treatment options and their associated prognoses.

Few experienced dentists have difficulty making treatment recommendations for their patients. Typically, those recommendations are based on what the dentist learned in dental school and what has been gleaned since, from continuing education courses, participation in study clubs, reading dental journals, and discussions with peers. In addition, dentists are commonly exposed to other, less objective sources of information. Examples include marketing of products and services via advertising in journals or on the Internet, or through corporate sales or dental supply representatives selling products or promoting techniques that may or may not have valid evidence to support their use. In the absence of such evidence, treatment outcomes may not be as the patient or dentist would expect, and there is greater potential for premature failure, a shortened lifespan for a restoration or prosthesis, and even harm to the patient.

For many dentists, the most important foundation on which treatment planning recommendations are made is the individual clinician’s own personal experience with a specific approach or technique. From a psychological perspective, there is often a powerful pull for practitioners to stay within their own comfort zone and continue to recommend treatments and perform procedures that are “tried and true.” The wise dentist will recognize the limitations and hazards of this approach. In the absence of scientific scrutiny, outdated, sometimes misguided, approaches have been perpetuated, whereas new and untried (by the practitioner) approaches are rejected out of hand. When the dentist fails to offer and make available a full range of treatment options to patients, or to accurately characterize the viability of each option, the quality of care provided to patients may be diminished.

The reality is that many treatment decisions in dentistry must be made in an environment of uncertainty, or in some situations, misplaced certainty. (For an example of the latter, see the section, When Should a Heavily Restored Tooth Be Crowned? later i n this chapter). The ability to make an accurate diagnosis, realistically predict outcomes of treatment, and delineate with precision the course of the disease with or without treatment is, in many cases, limited. That being the case, it behooves the dentist to place the ethical principle of nonmaleficence, or “do no harm,” in a position of preeminence. When the reasons for intervening are not compelling or when the risks of “no treatment” (i.e., watchful waiting) are not significant, then conservative therapy or no treatment should usually be recommended over aggressive therapy or treatment. The nature of the disease process certainly has a bearing on this analysis. Where there is diagnostic and/or treatment uncertainty, but the disease may have significant morbidity or mortality, as with oral cancer, aggressive intervention is generally warranted. On the other hand, when there is similar diagnostic uncertainty (as with incipient dental caries in a patient at low risk for new caries), and the short-term probability of negative sequelae (fracture, pulpal disease, or periapical disease) is low, then intervening conservatively and at a measured pace is more professionally reasonable.

Professional variability and disagreement in treatment planning

It is well established that dentists frequently differ with one another on specific diagnoses and, therefore, plans for treatment. Studies have shown that when several dentists examine the same patient under the same conditions (even in controlled experimental or teaching conditions), they often disagree on which teeth should be treated and how they should be treated. These differences are not limited to restorative treatment. Dentists disagree on how to manage and treat many oral problems, including periodontal disease, soft tissue lesions, and malocclusion. This is not necessarily a problem. If different practitioners can demonstrate with comparable positive outcomes measures that their varying plans are equally effective, there would be no reason for concern. Theoretically (as it is often impossible to measure), one treatment plan would be found to have a better outcome than the others if all could be followed over an extended period of time. In reality, it is probably the case that various approaches may each yield acceptable results, whereas some others would definitely be inferior. The appropriate goal, then, should be to ensure that the inappropriate plans can be identified. Before discussing ways to achieve this goal, the reader should have a clear understanding of why clinicians disagree.

Why dentists disagree in treatment planning

Inaccuracy of diagnostic tests

Even with conditions as pervasive as dental caries, our diagnostic tests are imperfect. Bader and Shugars, in their systematic review of dental caries detection methods, found relatively low mean sensitivity (true positive) and low mean specificity (true negative) for the visual detection of occlusal carious lesions, irrespective of lesion size, and very low mean sensitivity and high mean specificity for visual, tactile detection of occlusal carious lesions, irrespective of lesion size. A low mean sensitivity and good mean specificity for radiographic detection of proximal carious lesions, irrespective of lesion size, was also very wide. Newer diagnostic techniques (DIAGNOdent, VistaProof, CarieScan) may improve those numbers but may result in notable error rates. In one study on the detection of occlusal carious lesions, a laser fluorescent measuring device yielded improved sensitivity (94%) but lower specificity (82%) compared with expert examiners using conventional diagnostic techniques. At best, although some of these caries detection devices may be useful in complement with other approaches, as the researchers who have studied them suggest, they are as yet insufficient to support development of treatment plans without use of other examination resources. As new technologies and products emerge, clinicians must evaluate their effectiveness carefully when deciding whether or not to use them even as adjunctive tools. , Statistical measures of diagnostic accuracy (e.g., sensitivity/specificity ratio, percent of false positives) are also not ideal for commonly used clinical and radiographic caries detection methods. False-positive diagnoses for caries are particularly troubling, as they may lead to unnecessary treatment.

Misdiagnosis and disagreement on diagnosis

Dentists may disagree about diagnoses for a particular patient. These differences sometimes involve how certain sets of symptoms should be categorized. For example, there has been significant disagreement among dentists as to how temporomandibular disorders (TMDs) should be assessed, diagnosed, and managed. As an example of a different type of problem, general dentists have sometimes underdiagnosed the occurrence of periodontal disease in their patients—which has, in some instances, resulted in malpractice litigation. Even more dangerous are missed diagnoses of oral cancers. Differences may also exist at a patient, tooth, or surface-specific level. , Different practitioners examining the same patients frequently differ in their diagnoses of caries and restoration defects. Multiple reasons for these differences can be noted—the information base collected by each dentist may differ, the interpretations may differ, and the diagnostic options considered by each dentist also may differ.

Regardless of the reasons, if dentists cannot agree on the diagnosis for a patient, then inevitably consensus concerning the best treatment option or recommendation will not be possible.

Lack of risk assessment

With some oral conditions, an assessment of the patient’s risk can have a compelling influence on the overall treatment plan. Caries is a notable example. Caries risk assessment forms the cornerstone of the successful application of a minimalist intervention philosophy in the management of dental caries. A baseline caries risk assessment to identify those factors that will most likely contribute to the progression of the carious disease process is crucial for patients with evidence of active dental caries. Each individual presents with a slightly different caries risk profile, and the principles of a patient-centered approach to managing each case should also be applied to the individual diagnostic and treatment planning phases of dental care.

In spite of well-defined caries risk instruments (discussed later in section, Caries Risk Assessment ), there may be disagreements among practitioners about the patient’s level of risk. Even more problematic is the situation in which the dental team fails to assess risk altogether. When tooth-specific restorative treatment is planned for a low-risk patient, there is a tendency to over treat, placing restorations whether or not they are needed or indicated. Conversely, failure to recognize that a patient is at high risk will often lead to failure to address underlying causes of the disease, allowing the condition to progress unchecked.

Uncertain prognosis

In the absence of accurate patient, disease, tooth, and treatment-specific prognoses, treatment planning depends on individual clinical experience, and the determining factor becomes “what works in my hands.” This is an unstable and irreproducible base on which to build consensus on treatment planning. The lack of evidence-based prognosis determination leads to errors in planning for the individual patient and impairs profession-wide attempts to establish treatment parameters.

Limited availability or use of outcomes measures

An outcome of care is defined as the health state of a patient as a result of some form of medical or dental intervention. Outcomes measures provide a quantifiable and standardized method for comparing treatments. This is especially helpful in relation to oral conditions, such as TMDs, for which many different and sometimes conflicting treatment modalities have been described. Unfortunately, for many dental procedures, outcomes data are not available. Even when available, many practitioners do not choose to make use of them. In either situation, the dentist will have no dependable method of judging which treatment is most reliable and most likely to function the longest. Attempts to develop profession-wide treatment parameters have been slow to emerge. As a result, the individual dentist is often placed in the position of making judgments based primarily on personal experience, drawn from what has worked best in the past in his or her own practice.

Dentists’ varying interpretations of patient expectations

It has been confirmed that when several dentists each independently examine the same patient under controlled conditions, each may interpret findings and the patient’s wishes regarding treatment differently. Several plausible explanations for this variability can be noted. The dentist may be making assumptions about the patient’s wishes and listening selectively, or the dentist may have a preconceived idea about what the ideal treatment should be and then may present that plan in a more favorable light.

A related issue is the frequent disparity between the perceptions of the dentist and those of the patient. Patients’ expectations before treatment, and their satisfaction after treatment, differ significantly from those of the dentist. Patients and their dentists, in many cases, probably also have differing perspectives on what will be an acceptable or good result. If the expectations of the patient and the dentist are not in alignment, it is not surprising that different dentists will perceive a given patient’s expectations differently. The important take-home message here is for us to listen carefully to our patients to discern their particular needs and expectations during the process of developing the treatment plan.

Need for more and better information on which to base decisions

If the reader accepts the premise that more and better evidence will assist the dentist and patient in making sound treatment decisions, achieving truly informed consent and resulting in higher-quality care, then the question becomes, “What information is needed to achieve these ends?” A series of questions can be developed that, when addressed, will meet the needs of patients and practitioners. The questions are framed here from the patient’s perspective, but each can also be asked from the perspective of the dentist as the care provider for a specific patient.

Each patient has the right to ask and deserves to receive answers to questions such as the following:

- •

What specific problems do I have?

- •

What ill effects can these problems cause?

- •

Can the problems be controlled or eliminated?

- •

What treatment options are available to address these problems?

- •

What are the advantages and disadvantages of carrying out treatment X, treatment Y, or no treatment?

- •

What results can I expect from the various possible treatment options?

- •

What may happen if no treatment is performed?

- •

Am I at risk for ongoing or new disease?

To answer these questions, it will be useful to know the following:

- •

On the professional level : What is the general success rate for a particular procedure; what is the population-wide expected longevity of a particular type of treatment or restoration?

- •

On the provider level : What level of success has the individual dentist experienced with the procedure?

- •

On the patient level : What is the likely outcome for this procedure when it is implemented on this particular individual?

Unfortunately, these pieces of information are rarely available for any particular treatment option, not to mention for all possible options in a given clinical situation. Often there is available evidence to at least partially answer some of these questions, but where evidence does not exist, or if it exists but is not applicable to the patient-specific circumstances, the dentist must recommend treatment based on his or her own knowledge and personal experience, and the patient must make a corresponding decision based on that limited information.

Evidence-based decision making

Although the concept of evidence-based healthcare has been frequently discussed in the health sciences literature in the past few decades, an understanding of the importance of basing the practice of clinical treatment on research findings dates from at least the early twentieth century. , In the 1990s, the concept was formalized and reemphasized in the work of David Sackett, who defined evidence-based practice as “integrating individual clinical expertise with the best available external clinical evidence from systematic research.” Although Sackett wrote about the practice of medicine, his views apply equally as well to dentistry. Many dentists have been slow to integrate clinical epidemiology along with their own practice experiences and patients’ values in their treatment planning. David Chambers has contended that there is no systematic, high-quality, conclusive evidence to demonstrate the inherent benefit of evidence-based treatment planning. Nevertheless, it remains a critical part of our healthcare delivery system, and organized dentistry has taken a strong position in support of EBD. The American Dental Association (ADA) has reaffirmed the importance and role of EBD in its Code of Ethics, and the concept has been codified in the accreditation standards of North American dental education programs. , ![]() See eBox 3-1 for suggestions on how to find the best evidence.

See eBox 3-1 for suggestions on how to find the best evidence.

In any discipline of medicine or dentistry, students and practitioners should recognize and be familiar with the sentinel research—whether described in journal articles or textbooks—that has shaped development of the discipline and guided decision making in that field. The value of such work is demonstrated as it is cited in lectures, courses, teaching manuals, clinical protocols, policy statements, and published professional guidelines. Such work will also be referenced in subsequent studies that derive from the original work. These works have been recognized to advance knowledge on the topic, and in some cases, to establish or redefine foundational concepts of the practice of dentistry.

Developing a regular routine for reviewing and analyzing the dental literature is an important activity for the clinician who wishes to provide the best possible care to his or her patients. Scholarly journals are the most important source of current information about clinical care. Most disciplines have one or more associated periodic publications that review and publish current studies that have met established peer review standards. For the specialist, or for the generalist seeking current knowledge in a specific area, these journals are an important source of contemporary and authoritative information. The judicious reader will select high-quality peer-reviewed journals, recognizing that the manuscripts selected for publication in such journals have been reviewed by several experts in the subject area.

Although reports of controlled randomized clinical trials provide the most clinically relevant information, such studies are not always available (or even feasible) on a topic of interest, and less global reports must be used. Once the desired literature is obtained, it is up to the clinician to critically evaluate the report. It is not always easy to distinguish high quality from poor research, but given time and experience, practitioners will gain skill in evaluating the evidence. Good articles exist on how to critically analyze healthcare literature, and the new dentist should hone these skills. ,

In a given year, there will be a wide range of publications in the dental literature, and the general dentist will have time to critically read only a small portion of these. It will be important to be selective, choosing the most relevant and most highly regarded scholarly publications. One way to stay abreast of the breadth of the new literature is to locate and review articles and reports that identify, describe, and summarize the literature on a particular topic. Such reviews provide the reader with a summation of the findings from studies on the topic to date and may also include the author’s summary and evaluation of what the literature does and does not demonstrate, in what areas information is insufficient, and where more research is needed.

Published systematic reviews are a relatively recent addition to the dental literature. The authors of such reports critically review the literature on a particular topic. The systematic review includes a formal process for assessing the quality of research reported in a set of articles, analyzing and synthesizing findings according to specifically defined, predetermined criteria, and then, finally, drawing conclusions for clinical practice based on that careful and systematic assessment. When there is demonstrable evidence that meets established criteria, systematic reviews provide the most compelling support for clinical decision making in dentistry. Some notable repositories for EBD in general, and systematic reviews in particular, are:

- •

The ADA’s Center for Evidence-Based Dentistry at http://ebd.ada.org/Default.aspx

- •

The Cochrane Library, which has a dentistry and oral health section, at . Most Cochrane reviews are current, and topics are often updated as additional research on the topic becomes available.

- •

PubMed. For the dentist in clinical practice, PubMed can provide an efficient way to find articles on a specific topic. Found at , PubMed is a free database produced by the National Library of Medicine (NLM) and draws on the resources of the MEDLINE database, an online index to the world’s health sciences journal literature since 1966. Many dental journals, in additional to traditional paper versions, are now also available as online subscriptions.

- •

Google Scholar ( ) is an easy-to-use search engine based on a popular operating system.

- •

TRIP ( http://www.tripdatabase.com ) is an easy-to-use clinical search engine with a dental section that has been online since 1997. TRIP originally stood for Turning Research Into Practice.

Two English-language journals focus specifically on EBD: Evidence-Based Dentistry , published in Britain , and the Journal of Evidence-Based Dental Practice (JEBDP), published in the United States. These journals publish what they term “summaries” and “analysis and evaluation” pieces. The Journal of the American Dental Association (JADA) publishes “critical summaries” of systematic reviews and 2- to 3-page peer-reviewed articles summarizing a systematic review, along with a critical appraisal of its methods and conclusions. For the busy practitioner, regular use of such journals is often the best way to efficiently and reliably stay current in evidence-based information in dentistry.

One must be aware, however, that just because a systematic review has been published on a particular subject, it may not necessarily provide the information needed to make a clinical decision. Any review may conclude with the statement that there is insufficient evidence to form a recommendation, or to distinguish between alternative treatments, and that further research is needed.

Several developments have already had an impact on treatment planning patterns and can help guide the treatment planning process for the individual patient. One approach has been the development of decision pathways specific to dentistry. These provide direction in identifying the range of treatment options, indicating some of the key decision nodes leading to appropriate treatment decisions. Decision pathways have been developed to cover a wide array of dental situations and procedures. In 1994, Hall and coauthors wrote a comprehensive treatment planning text using this format. Since then, several authors have contributed to this field. By providing a template for decision making and patient presentation, decision pathways can be particularly helpful to the novice. They can be useful to the experienced practitioner as well by providing a restatement of the range of options that should be considered. Their most significant limitation is that they tend to be somewhat cumbersome for routine daily use, especially for the experienced practitioner who has learned to intuitively sort out which issues are important for a specific patient, dismissing decision nodes that are not applicable.

Decision trees represent a more sophisticated expansion on this theme. Decision trees not only specify key decision nodes and treatment options but also include research-based success rates for each of these options. The rates can be based on outcomes of clinical conditions (e.g., effect of tooth loss) or on outcomes of treatment (e.g., success of various therapies for tooth replacement). Decision trees may also be influenced by patient-related variables, such as the patient’s preferences, expectations, and financial resources.

In theory, comprehensive decision trees would be useful for the patient treatment planning discussion, but unfortunately, to date, they do not exist for most clinical situations. Decision analysis has already been applied to several areas, including radiographic selection, , endodontic treatment, management of exposed dentin and dentin hypersensitivity, guided tissue regeneration, treatment planning of compromised teeth, management of the endodontically abscessed tooth, management of apical lesions after endodontic treatment, restorative dentistry, , and TMDs. , See Suggested Reading and Resources at the end of the chapter for representative Decision Pathways and Decision Trees.

Risk assessment

Risk assessment and dental treatment planning

Risk indicators are identifiable conditions that, when present, are known to be associated with a higher probability of the occurrence of a particular disease. Risk factors are conditions for which a demonstrable causal biologic link between the factor and the disease has been shown to exist. Risk factors are best confirmed by longitudinal studies during which patients with the hypothesized risk factor are evaluated over sufficient time to determine whether they do or do not develop the specific disease or problem in question. Risk indicators may be identified by taking a cross section, or sample, of individuals and looking for instances of the risk indicator and the disease occurring together. Although risk and causality may be linked, they are not the same. For example, a diet that is heavily laden with refined sugars constitutes a risk indicator (and a risk factor) for caries. However, a specific patient who consumes a highly cariogenic diet may never be afflicted with caries.

Another categorization that is particularly useful to keep in mind in the dental setting is the distinction between mutable (modifiable) and immutable (nonmodifiable) risk factors or risk indicators. Mutable risk indicators—such as diet, oral self-care, smoking, poorly contoured restorations—can be changed, whereas immutable risk indicators, such as age, genetics, or fluoride history, are factors that cannot be changed. The dental team can and should use any and all reasonable interventions that have the potential to mitigate or eliminate mutable risk indicators. In the case of immutable risk indicators, however, the value of their identification may be limited to risk assessment and guiding the prescription of preventive therapy—which can be useful tools in health promotion and oral disease prevention.

Assessing risk assists the dentist in identifying which patients are more likely to develop a particular disease or condition or to have recurrence of the disease. When that identification has been made, the patient can be informed about the risks and, when feasible, efforts can be made to eliminate or mitigate the specific cause or causes of the disease. When successful, such efforts help the patient preserve his or her dentition. Elimination of a specific cause or causes of an oral disease early in the progression of the condition can, in some cases, reduce the severity and the duration of the disease (e.g., periodontal disease). Once the disease process is initiated, however, removal of a risk indicator or indicators that are not known to be direct causes of the disease may have no effect on the duration or course of the disease (e.g., oral cancer).

To describe the strength of the relationship between risk and future disease occurrence, it is often helpful to specify the degree of risk with terms like “high,” “moderate,” or “low.” Defining the degree of risk varies with the clinical context or with the parameters of the individual study or protocol. In any setting, it can be assumed that the higher the risk, the more likely the occurrence or recurrence of the disease. In the presence of multiple risk indicators and/or strong risk indicators, the occurrence of disease is also more likely. For example, in general, the patient who has multiple risk indicators for dental caries (e.g., lack of previous and current fluoride exposure, and a cariogenic diet) is more likely to be afflicted by dental caries than a patient with only one or no known risk indicators. Also, as discussed later in this text, an older adult patient with a strong risk indicator (e.g., xerostomia ) is more likely to develop dental caries than a similar patient with a less strong risk indicator, such as lack of fluoride exposure as a child.

Eight categories of conditions or behaviors that may be risk indicators for oral disease can be described and are discussed in the following sections. It must be noted that, although the categories and their relevance to treatment planning are presented here as distinct entities, many potential risk indicators do not fit neatly into a single category, but may appropriately be placed in two or more.

Heritable conditions

Heritable conditions include the genetic predisposition for specific tooth abnormalities, such as amelogenesis imperfecta, dentinogenesis imperfecta, dentinal dysplasia, or extradental abnormalities, such as epidermolysis bullosum, a palatal cleft, or a skeletal deformity. Recent genome-wide association studies have found potential genetic components to caries, which heretofore had not been thought to exist. ,

The presence of a genetic marker for any hereditary or developmental oral abnormality would certainly be an indicator of risk. Knowledge of such risk indicators can be useful to the dentist and patient in the following ways:

- •

Genetic counseling: The dentist plays a role in identifying oral conditions and anomalies that may be heritable. When such conditions are recognized, the patient as a potential parent can be encouraged to seek genetic counseling. Also, parents who have had one child with a genetic disorder will be very interested in the probability that other progeny will be similarly affected.

- •

Patient education: With awareness that a patient is at risk for developing an oral disease, it becomes part of the dentist’s role to educate the patient about the true cause of that process. Some patients may mistakenly think that the heritable condition is caused by factors that are in their control and will go to unusual lengths in a misguided and sometimes harmful effort to control the disease. Taking antibiotics to control the “infection” associated with a normally erupting tooth is one such example. Conversely, some patients assume that certain conditions, such as “soft teeth,” are totally controlled by “genes” and that they can do nothing to prevent caries. Educating patients about the multiple contributing causes of dental caries can be helpful in leading to effective means of controlling the caries and giving the patient a clear sense that his or her condition is not hopeless.

- •

Disease prevention: If a family history of a heritable oral condition is known, it may be possible for measures to be taken to prevent or at least mitigate the occurrence of the disease in susceptible individuals. Eliminating other risk factors and/or known causes of the disease would be one such strategy.

- •

Early recognition: With awareness that a patient is at risk for a heritable oral condition, the dentist and patient can carefully monitor for early signs or symptoms of change. Through such efforts, laboratory tests or other confirmatory information can be obtained at an early point and a timely diagnosis made.

- •

Early intervention: Early intervention by the dentist may be effective in preventing full manifestation of the inherited condition and reducing morbidity. Intensity and/or the longevity of the outbreak may be decreased and recurrence prevented. Aggressive periodontitis is an example of a sometimes heritable oral disease that, if treated early, has a much improved prognosis.

Systemic disease as a risk indicator for oral health problems

Patients with gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) are at significantly increased risk of developing dental erosion. , Similarly, patients who are afflicted with bulimia are also much more likely to have dental erosion. Leukemia may cause a wide variety of intraoral soft tissue abnormalities. Advanced liver disease is a risk factor for intraoral ulceration, petechial formation, ecchymosis, and bleeding. Systemic diseases such as diabetes can be risk factors, predisposing the patient to significant oral problems, such as oral ulceration, stomatitis, infection, and poor wound healing. The poorly controlled diabetic patient is more likely to develop and exhibit progression of periodontitis. Some evidence suggests that periodontal disease is modestly associated (10%-50% increase in risk) with atherosclerotic vascular disease and clinical events, and that this association is independent of other shared risk factors. Some uncertainty remains, however, about the existence of such independent associations between periodontal disease and atherosclerotic vascular disease. A systematic review suggests that treatment of periodontal disease improves endothelial function and reduces biomarkers of atherosclerotic disease, especially in those already suffering from cardiovascular disease and/or diabetes.

Many other general health problems are risk factors for intraoral pathology. Some of these are detailed in Chapter 7 , and a range of medical issues that place a patient at risk for oral pathology is addressed in the suggested readings accompanying that chapter. When the patient has a systemic disease, the dentist must be aware not only of related risks for developing oral disorders; but also the possible need for antibiotic premedication, the advisability of modifying or postponing dental treatment, and, in some cases, the need to be prepared for a medical emergency in the dental office.

Dietary and other behavioral risk indicators

If the patient’s behavior, diet, or habits contribute to an increased risk for the development of oral disease, then it is appropriate for the dentist to educate the patient about those risks and encourage modification or elimination of the behavior. Use of tobacco products, excessive alcohol consumption, oral use of cocaine or methamphetamines, or frequent ingestion of cariogenic foods and beverages are examples of behavior that can be deleterious. On occasion, overuse or misuse of normally beneficial habits may cause significant problems. One example is the frequent use of low-pH and/or high-alcohol-percentage mouth rinses by a xerostomic patient. The dentist has the responsibility to recognize the problem, inform the patient of the risks (i.e., possible negative consequences of continuance), and to remain vigilant for the occurrence of signs suggestive of pathologic developments, such as dental erosion or oral cancer. , An example of a psychological and behavioral problem linked to an oral pathologic condition is the patient with obsessive-compulsive disorder who is at risk for the development of severe dental abrasion and other traumatic or factitious injuries.

Risk indicators related to stress and anxiety

Patients can be at risk for many forms of oral pathologic conditions because of significant life stresses or other environmental influences. Erosive lichen planus is an example of an oral condition for which stress is a strong risk factor. An all-too common problem is the patient whose anxiety about going to the dentist leads to avoidance of needed treatment. As discussed in Chapter 14 , the implications for the anxious patient of the development of oral problems and the potential effect on the way dental treatment will be planned and carried out can be enormous. The dentist has the obligation to identify these risk indicators, inform the patient of their deleterious potential, and mitigate them whenever possible.

Functional or trauma-related conditions

Functional or trauma-related conditions also incur risk. For example, the patient who bruxes and has fractured teeth in the past should be assessed for current and future risk of recurrence. If the patient continues to be at risk, then appropriate reconstructive and/or preventive measures should be considered. For the patient with severe attrition, large existing amalgam restorations, and a history of fractured teeth, sound recommendations may be crowns and an occlusal guard. If new restorations are warranted, but the patient cannot afford crowns, using a protective cusp design rather than a conventional preparation design for direct fill restorations may be a reasonable alternative. Another example: When a tooth is acutely traumatized, it is not uncommon to later develop pulpal necrosis, periapical pathology, and/or tooth or root resorption.

Environmental risk indicators

Food service workers, who have constant and unlimited access to sweetened and carbonated beverages, are at increased risk for both dental caries and dental erosion. Frequent swimming in pools with chlorinated water can cause significant dental erosion in susceptible individuals. Patients who are allergic to certain foods, latex, metals, or other environmental agents may develop ulceration, stomatitis, hives, or, less commonly, an anaphylactic reaction. Obviously, the best strategy in managing these patients is to eliminate exposure to the allergen or allergens. Sometimes this can be difficult. For example, because peanuts and peanut products are ubiquitous in the North American processed food chain, the patient who is very reactive to peanuts may have difficulty in avoiding exposure.

Socioeconomic status

The validity of socioeconomic status as a risk factor in oral health problems is uncertain. Although caries, periodontal disease, and tooth loss are more prevalent in individuals from lower-income groups, it often remains unclear whether the disease process is the consequence of poor nutrition, low self-esteem, lack of health literacy, or lack of access to healthcare. Even if one accepts low socioeconomic status as a risk indicator for certain oral conditions on a population-wide basis, there is little support for the assertion that it is a risk factor for a specific patient’s disease state. For the individual patient, socioeconomic status must always be considered to be a mutable, never an immutable, factor. (See Chapter 18 for a more specific discussion of the needs of patients who are motivationally compromised or who have limited financial resources.) The important take-home message here is that socioeconomic status should not be seen as a limitation to treatment, but rather as a window of opportunity to help the patient achieve a more optimal state of oral health. An open and honest conversation with the patient about his or her personal challenges and difficulties will often provide an opportunity to build rapport and help to ensure that the treatment plan will be relevant and appropriate.

Previous disease experience

Previous disease experience can be a strong predictor—in some cases, the single best predictor—of future disease. For many oral conditions, including dental caries, periodontal disease, oral cancer, and tooth fracture, if the patient has experienced the problem in the past, the probability is greater that the same problem will arise again in the future.

Because past disease experience is an immutable risk indicator, the best management strategy is to identify other causes of the condition and mitigate or eliminate those whenever possible. Treatment interventions should be recommended and instituted to prevent recurrence. Placement of a cusp protective restoration on a tooth at high risk for fracture is one such example.

To summarize, risk assessment can be a useful adjunct to the dental treatment planning process in the following ways:

- •

Identifying the need for counseling the patient, spouse, or offspring about heritable oral conditions and diseases

- •

Working to eliminate recognized causes of oral disease when the patient is known to be at risk

- •

Initiating preventive measures to forestall the occurrence of oral disease when potential causes of oral disease cannot be eliminated

- •

Providing prophylactic behavioral, chemotherapeutic, and restorative intervention to prevent an undesirable outcome

- •

Providing early restorative intervention in situations in which delayed treatment would put the patient at risk for requiring more comprehensive treatment in the future

In theory, with a complete understanding of the patient’s risk for oral disease, any oral disease for any patient could be prevented or, at least, managed more effectively. In clinical practice, this is not feasible or practical. Time would not permit so exhaustive a review for every patient, and our present scientific base is insufficient to support such an undertaking. Nevertheless, assessing risk provides a valuable resource in treatment planning. In the following discussion, four oral conditions are described in which risk assessment should be critically linked to shaping the patient’s plan of care.

Oral cancer risk assessment

Oral cancer is a generic term applied to any malignancy affecting the oral cavity and/or jawbones. The majority of primary malignancies occurring in the mouth derive from the surface stratified squamous epithelium of the oral mucosa. Other primary oral cancers include malignant neoplasms of salivary gland origin, sarcomas in soft connective tissue or bone, lymphomas, melanomas, and odontogenic carcinomas. Secondary or metastatic cancers, originating from any distant organ or tissue (e.g., breast, prostate, colon, liver), may also occur in the mouth. The following discussion focuses on oral squamous cell carcinoma, because this diagnosis represents more than 80% of cases of oral cancer.

Oral squamous cell carcinoma (OSCCA) is the result of the malignant transformation of keratinocytes in the surface epithelium. The epithelium usually undergoes a progressive transformation from normal, to dysplastic, to invasive carcinoma. However, such a progression may be very rapid and the dysplastic changes may not be detected early or are only recognized after invasive carcinoma ensues. Dysplasia or carcinoma may present clinically as a white, red, white-red, ulcerated, verrucous lesion, or as a combination of these characteristics. Sometimes patients will develop more than one lesion with dysplasia.

Several substances and behaviors are known to contribute to the initial formation of OSCCA. Even with eradication of the lesion by surgical excision or other means, the patient remains vulnerable. In particular, if exposure to carcinogens continues, the patient is at risk of cancer recurrence or development of additional lesions in other oral sites (second primary tumors).

Risk factors for oral cancer

Tobacco.

Any form of tobacco has the potential to induce carcinogenesis of the oral epithelium. This is a dose-dependent phenomenon. Patients with a history of having used any tobacco products within the last 10 years should be considered at relatively high risk for OSCCA. The type of tobacco, frequency of use, and duration of use must be documented and monitored. Patients who are exposed to tobacco, including second-hand smoking, should be counseled to avoid it.

Alcohol.

Ethanol use is believed to be a cofactor for OSCCA through altering the local environment of the oral mucosa to favor carcinogenesis, by inducing genetic alterations in the cells at the local level, and also by changing the systemic processing of other carcinogens and altered cells in the liver and the entire organism. , The type, amount, and frequency of alcohol consumption should be documented, monitored, and discouraged if it is determined to be excessive.

High-risk human papillomavirus infection.

Recently, the association of high-risk subtypes of human papillomavirus (HPV; example, HPV 16 and HPV 18) has been linked to oral cancer. The profile of the patient who develops OSCCA in the presence of HPV is different (often nonsmoker, nondrinker, educated, middle aged, male homosexual, or partner with HPV), the lesions tend to be found in a different location (oropharynx), and the OSCCA generally responds more favorably to treatment.

Trauma.

Although trauma per se does not cause carcinogenesis, it may induce epithelial damage and subsequent repair. The repair of epithelium demands cell duplication and, by increasing the cells that undergo division, the possibility that one of those cells will develop mutations and undergo neoplastic transformation is increased. Lesions that are determined to be of traumatic etiology must be resolved and the source of trauma eliminated to avoid unnecessary cell division and the possible increased risk of neoplastic change.

Immune system compromise and immunosuppression.

If the immune system of a patient is compromised (as with a debilitating disease) or suppressed (as caused by taking corticosteroid drugs), its ability to destroy transformed neoplastic cells is decreased, allowing tumors to grow unchecked. As a result, patients who are immunocompromised or immunosuppressed are at greater risk of developing oral cancer.

Radiation treatment.

Patients undergoing radiation therapy for head and neck malignancies often experience multiple side effects (see Chapter 5 ). Several of these, including xerostomia dermatitis, mucositis, tissue atrophy, and hypovascularity, may be contributing factors to new or recurrent cancer development. In some cases, radiation induces malignant transformation or de-differentiation of preexisting tumors. Common neoplasms that develop owing to radiation include osteosarcoma and fibrosarcoma. The damage induced by radiation is dose dependent.

Xerostomia.

Xerostomia may contribute to mucositis and traumatic lesions (micro- and macroulceration). Although some authors have associated the presence of chronic candidiasis with oral cancer, the evidence is not definitive on this issue.

Antineoplastic chemotherapy.

Antineoplastic agents can affect the oral cavity in a variety of ways. Common complications in patients undergoing chemotherapy are dry mouth and mucositis. Some chemotherapy protocols include agents that also severely suppress the patient’s immune system, in which case the risk for oral cancer may be increased. Other types of chemotherapy, although not directly associated with increased risk of oral cancer development, may still result in significant undesirable side effects to the oral mucosa or jawbones, such as thinning of the oral mucosa, which may indirectly contribute to carcinogenesis.

Malnutrition.

Malnutrition can be associated with delayed wound healing, immune system malfunction, or decreased cellular repair. Patients with poor nutritional status may have an increased risk for development of oral cancer.

Previous history of oral cancer.

Patients with previous histories of oral cancer should be monitored carefully for recurrences or second primaries. In the patient with a history of cancer at a site other than the oral cavity, the possibility of metastatic disease should always be considered in the differential diagnosis of any oral lesion that cannot be diagnosed clinically. Therefore, in the patient with a history of any type of cancer, any and all oral lesions should be biopsied unless the clinician can be certain of its diagnosis based on clinical evaluation alone.

With the identification of risk factors or risk indicators for oral cancer, every effort should be made to eliminate those factors and educate the patient about oral cancer. Strategies for smoking cessation are presented in Chapter 9 , and management of alcohol abuse is discussed in Chapter 13 . When the discovery is made by the dentist at the initial oral examination, it is imperative that the dentist evaluate additional specific areas of vulnerability during the course of the clinical examination (e.g., area of the lip where cigarette is held, vestibular site where snuff or chew is harbored, site of buccal mucosa adjacent to a sharp tooth fragment or broken restoration, floor of the mouth/ventral tongue in smokers, pharyngeal area in cases of HPV risk). When it is possible to eliminate local sources of tissue trauma (e.g., a defective restoration), that should be accomplished early in the treatment plan. Any lesion that cannot be clinically diagnosed or unequivocally associated with trauma must be biopsied for diagnostic pathology. Management of other questionable lesions is discussed in Chapter 1 . If the risk indicator(s) for oral cancer cannot be eliminated, then the patient must be carefully monitored as long as the individual remains in the practice. Patient education about oral cancer risk factors should be ongoing.

Caries risk assessment

Some clinical conditions (such as the presence of plaque) and behavioral patterns (such as frequent fermentable carbohydrate consumption) have strong associations with the occurrence of dental caries. Nevertheless, the presence of those factors alone has been shown to have limited predictability of current or future caries activity.

Recent caries experience and current disease activity continue to be the most important factors for predicting future caries activity. Past caries experience represents the combination of many risk factors to which an individual has been exposed over a long period of time. Current dental caries activity represents recent exposure to risk factors and, if those factors remain unchanged, suggests a high likelihood of continuing caries activity in the future. It is unfortunate that dentists must rely on the appearance of clinical signs of the disease to have a high degree of certainty about future risk determination, but, on the positive side, detecting caries lesions is a relatively simple and inexpensive clinical activity, and early detection of lesions and the elevation of caries risk can lead to early and effective management of both risk factors and the disease process.

To diagnose, assess the risk level, and effectively manage active dental caries, an array of information must be obtained. Collecting information on risk factors such as presence and location of stagnant plaque, regularity of consumption of fermentable carbohydrates (particularly between meals), and salivary flow levels, along with information about protective factors, such as fluoride exposure and the presence of sealants, will provide the dental team and patient with an understanding of the causes and origins of the caries activity. This information will also be used to develop an individualized management plan for the patient (see Chapter 9 ).

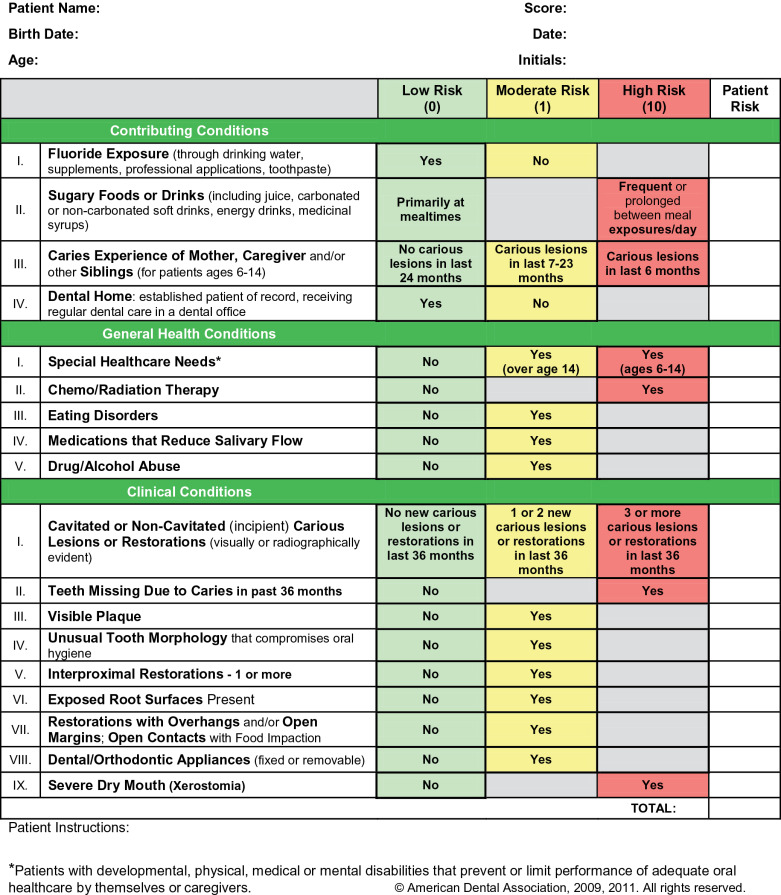

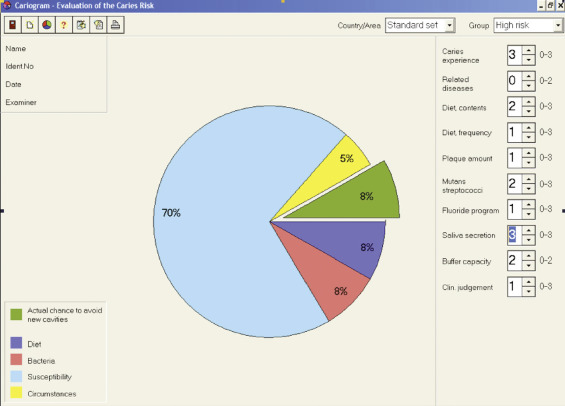

Several dental organizations have developed caries risk assessment modules, designed with the primary purpose of determining a patient’s level of risk based on identified risk factors, as well as protective factors that are believed to be closely associated with limiting dental caries progression. Several of these instruments are available at dental organization websites or in recent publications (see Suggested Readings and Resources at the end of this chapter). Two notable examples include the Caries Management by Risk Assessment (CAMBRA) group ( Figure 3-1 ) and the Cariogram software program developed at the University of Malmö in Sweden ( Figure 3-2 ). These risk assessment modules have been developed primarily based on expert opinion, and limited evidence is available on their validity. In addition, the use of the modules in adults is based primarily on evidence from younger groups, because most of the reported studies have been conducted on younger age groups.

To determine the risk level, the modules combine caries indicators (caries lesion presence in recent years), risk factors, and protective factors. In general, a patient is considered to be at low risk when no active caries lesions have been found in the last 3 to 5 years, combined with no recent changes in risk and protective factors. Patients considered at moderate or high caries risk are those presenting with recent caries lesions and/or detrimental changes in risk or protective factors. The following cases are examples of some of the types of patients who should be considered to be at elevated caries risk:

- •

A patient with apparently good oral hygiene but with new caries lesions, providing clear evidence that current risk factors result in development of lesions

- •

A patient with no new detectable caries lesions but a recent severe drop in salivary flow due to a new medication

- •

A patient who has been using fluoridated toothpaste all her/his life and with no caries activity in the last few years but who has recently decided to stop using fluoride. This patient will have a significant diminishing of the protective factors, potentially leading to dental caries activity.

All patients with these characteristics should have individualized management to reduce the risk of developing new lesions.

Although collecting caries risk information regularly is perceived as an extremely time-consuming process for the busy practitioner, most of the needed information is readily available via a well-conducted medical/dental history and examination. In most instances, no additional testing is necessary. In fact, the practitioner’s subjective assessment based on clinical experience is a useful determinant of risk. Nevertheless, systematic collection and recording of objective data are important for consistency across multiple members of the dental team, for monitoring progress of the caries management plan, and for legal protection.

Although many of the risk and protective factors associated with development of both root caries and recurrent caries are similar to those for coronal caries, there are a few unique aspects of root caries development and occurrence that the practitioner should be cognizant of. Root surface exposure to the oral environment is a prerequisite for the development of caries lesions on the root surface. The drop in biofilm mineral saturation necessary for demineralization of the dentin/cementum is less than that needed for enamel demineralization, suggesting that root caries lesions can be developing while enamel surfaces are unaffected. Nevertheless, there is a clear association between root caries and active coronal caries. In the United States, men exhibit a higher prevalence and greater severity of root caries. As for coronal caries, individuals with higher income and more education exhibit a lower prevalence of root caries. Importantly, however, most of these differences tend to disappear later in life. It is of particular importance to continue monitoring patients when they enter their later years in life, as salivary, dietary, and oral hygiene behaviors frequently change.

For secondary caries, the quality of the tooth-restoration interface is of particular importance, especially in the interproximal areas where most of these lesions develop. Large gaps between the tooth and restorative material have been associated with increased caries development. Gaps that can be penetrated with the tip of an explorer tend to be wider than 100 mm and should be considered a high-risk location for secondary caries development.

Once a patient has been determined to be at increased risk of caries, the patient needs to be informed, risk indicators discussed, and an appropriate intervention put in place. The basic caries control protocol and optional interventions to manage the patient with active caries are described in Chapter 9 . It is also essential to continue to monitor the patient’s caries activity and reassess caries risk at periodic intervals. Caries risk may diminish, increase, or remain static over time. The dental team must be vigilant to ensure that any increase in caries risk status is recognized and that aggressive intervention can be implemented.

Periodontal disease risk assessment

Periodontal risk assessment gained attention in the dental literature in the early 1990s. Efforts have been made to characterize periodontal risk by quantifying clinical and radiographic findings and applying these values to validated algorithms. These tools look at a number of parameters that, when input, will generate a summarized report categorizing the risk level and suggesting treatment strategies. Assessed parameters include the following:

- •

Probing depth

- •

Bleeding on probing

- •

Tooth loss

- •

Extent of radiographic bone loss

- •

Patient age relative to extent of disease

- •

Diabetes mellitus

- •

Genetic factors (interleukin [IL]-1 genotype status)

- •

Cigarette smoking

- •

Tooth-related factors (presence of furcation involvement, vertical bone loss, subgingival restorations, and/or calculus deposits)

- •

Treatment history (previous nonsurgical and/or surgical periodontal therapy)

Evidence of linkage between periodontal disease risk and patient outcomes has been reported ( Box 3-1 ). Patients who have been determined to be at high risk for periodontal disease have been shown to have higher rates of tooth loss, even when compliant with treatment. Periodontal risk assessments have also been shown to be predictive of treatment outcomes. ,

- •

Age

- •

Smoking/tobacco use

- •

Genetics

- •

Stress

- •

Medications

- •

Clenching/bruxism

- •

Systemic diseases (cardiovascular disease, diabetes, rheumatoid arthritis)

- •

Poor nutrition and obesity

Periodontal disease risk assessment should be completed as part of any comprehensive or periodic dental examination. Given the slow and often occult progression of most periodontal diseases, even younger adults will benefit from such an assessment. Assessing periodontal risk gives both the clinician and the patient a framework in which to discuss treatment and prevention strategies. Such an assessment helps to identify those factors that can or cannot be modified that will ultimately guide the long-term management of the patient. Consequently, a comprehensive assessment of a patient’s periodontal risk factors is necessary throughout care. The American Academy of Periodontology website includes a “Gum Disease Risk Assessment Test” that can be utilized by the individual patient to assess his or her own periodontal risk (see Suggested Readings and Resources ).

Effective early management strategies should address modifiable risk factors. Possible therapies for patients with risk factors for periodontitis include the following:

- •

Oral hygiene instructions to review plaque removal techniques

- •

Smoking cessation, including referrals to other healthcare professionals as needed

- •

Referral to a physician for diabetes management

- •

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses