Armamentarium

|

History of the Procedure

Palatal and mandibular lingual tori are relatively common bony outgrowths recognized since the 19th century as benign, typically incidental, findings. One of the first English-language papers describing tori was published in 1909 in the Proceedings of the Royal Society of Medicine (Surgical Section) by Rickman Godlee, who describes maxillary tori encountered by himself and dentist collaborators. He refers to an earlier, detailed description in a German Festschrift commemorating Virchow’s 70th birthday in 1891, and agreed with that paper by advising against tori removal in most cases. By the mid-20th century, numerous authors described the prevalence of both palatal and lingual (mandibular) tori in a variety of ethnic populations, nicely summarized by Garcia-Garcia. Larger, more recent studies find tori in 10% to 50% of the population, with maxillary more common in women, and mandibular tori generally less frequent but, in most studies, more common in men. Tori of the upper and lower jaws appear to occur together in the same patient infrequently. Techniques for removing tori have been described in standard oral surgery textbooks since the mid-20th century and are largely unchanged, although recent literature has proposed innovations such as guided surgery to address highly unusual circumstances.

History of the Procedure

Palatal and mandibular lingual tori are relatively common bony outgrowths recognized since the 19th century as benign, typically incidental, findings. One of the first English-language papers describing tori was published in 1909 in the Proceedings of the Royal Society of Medicine (Surgical Section) by Rickman Godlee, who describes maxillary tori encountered by himself and dentist collaborators. He refers to an earlier, detailed description in a German Festschrift commemorating Virchow’s 70th birthday in 1891, and agreed with that paper by advising against tori removal in most cases. By the mid-20th century, numerous authors described the prevalence of both palatal and lingual (mandibular) tori in a variety of ethnic populations, nicely summarized by Garcia-Garcia. Larger, more recent studies find tori in 10% to 50% of the population, with maxillary more common in women, and mandibular tori generally less frequent but, in most studies, more common in men. Tori of the upper and lower jaws appear to occur together in the same patient infrequently. Techniques for removing tori have been described in standard oral surgery textbooks since the mid-20th century and are largely unchanged, although recent literature has proposed innovations such as guided surgery to address highly unusual circumstances.

Indications for the Use of the Procedure

In most cases, palatal and lingual tori are benign, asymptomatic, and do not require removal. When a dental prosthesis will cover the palate, a large palatal torus will interfere with the prosthesis and may compromise its success. Similarly, the major connector or flange of a mandibular partial or complete denture cannot be adapted successfully to the alveolar ridge if mandibular tori are present. In these cases, tori should be removed.

In some patients, unusually large palatal tori are prone to traumatic injury to their thin mucosal covering, causing recurrent, painful ulcerations. Similarly, very large mandibular tori may either be subject to traumatic injury or, in extreme cases, interfere with tongue movement. In these situations tori are mechanical impediments to healthy oral function and should be removed.

Several authors have described techniques for successful use of either maxillary or mandibular tori as donor sources of autogenous bone for intraoral grafting procedures. In cases where the quantity of donor bone required matches the size of available tori, this is an attractive means to obtain the required bone from a site where bone removal may actually be advantageous to the patient.

Limitations and Contraindications

Because torus removal is almost always a routine, elective procedure, patients should be counseled in advance regarding the expected perioperative course and potential risks or complications. A clear indication should exist to justify the planned procedure. Any medical comorbidities that might complicate minor dentoalveolar surgery or its outcome should be managed to an optimized state, particularly those that might lead to excessive bleeding, reduced resistance to infection, or poor soft tissue healing. Any adjacent dentition should be healthy and demonstrate good oral hygiene before torus removal. As with all elective dentoalveolar surgery, the expected benefit of the operation should be weighed carefully against the potential risks. This is especially true in patients with serious health problems, and often it is elderly and potentially frail patients who seek torus removal as a step toward better dental prostheses.

Technique: Palatal Torus Removal

Step 1:

Incision

Palatal tori are found in the posterior midline of the hard palate and vary dramatically in their size and morphology. Some are narrow in lateral dimension and elongated anteroposteriorly, and others are dome-shaped. Large tori tend to be shaped in multiple lobes with varying symmetry, sometimes with deep clefts between the lobules. Often larger tori have relatively small bases and are thus somewhat pedicled at their connection to the hard palate. In all cases, the entire torus must be exposed to allow its removal. The morphology of a given torus dictates the incisions required to expose it.

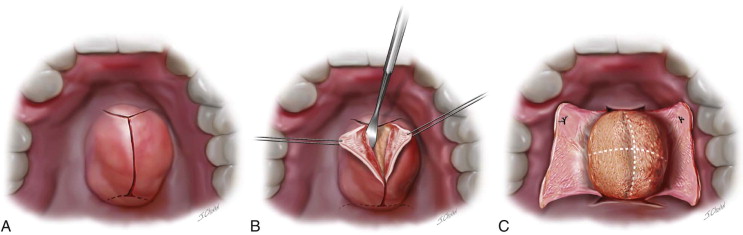

The most commonly used incision design is a “double-Y.” A midline incision is made anteroposteriorly from a point several millimeters anterior to the margin of the torus. This full-thickness incision is carried to bone posteriorly until it reaches the most posterior visible point on the torus, or a point approximately a centimeter anterior to the hard-soft palate junction. Care should be taken to leave room for posterior releasing incisions to extend obliquely in a lateral and posterior direction from the posterior end of the midline incision without violating the soft palate. Completing these posterior releases is sometimes easier after the bulk of a large torus has been exposed or even removed. At the anterior end of the midline incision, oblique releasing incisions are extended laterally and anteriorly to end lateral to the lateral margins of the torus ( Figure 14-1, A ).

Step 2:

Soft Tissue Reflection

A #9 Molt periosteal elevator is used to reflect the thin overlying soft tissue from the torus. In tori with deep groves between lobes, a finer instrument such as a #1 Woodson elevator may help loosen the attachments without tearing the delicate mucosal layer. Usually the soft tissue is adherent in the surrounding clefts and grooves but covers the smooth surface of the torus loosely, allowing easy reflection of the full-thickness mucoperiosteal flap from the surface of the torus itself ( Figure 14-1, B ).

Step 3:

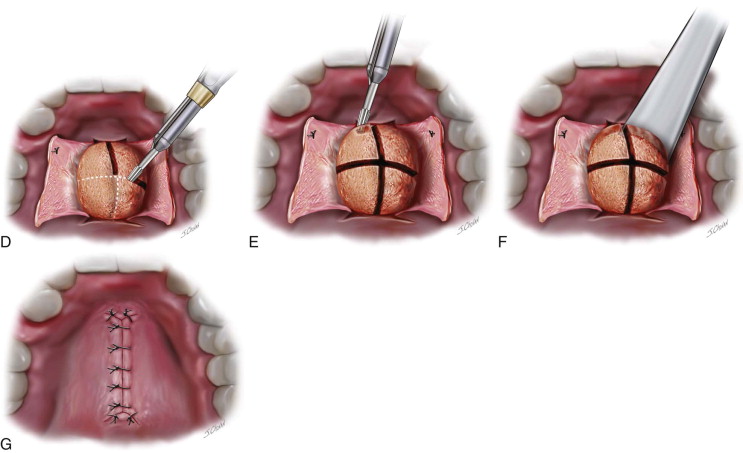

Ensure Full Exposure of the Torus

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses