The use of regenerative endodontic techniques holds great promise for the treatment of immature teeth with necrotic pulp tissue. Several published case reports and case series have demonstrated radiographic evidence of apical bone healing, increases in root length, and root wall thickness. Although histologic changes have been demonstrated in animal models, histology in human teeth is lacking. A summary of these outcomes is discussed in this article.

- •

Radiographic evidence of apical bone healing, increased root length, and increased root wall width has been shown after the use of regenerative endodontic techniques in human teeth with immature roots and necrotic pulp tissue.

- •

The histologic evidence from animal models using similar regenerative procedures has shown varied hard and soft tissues in the canal space.

- •

Future research should focus on demonstrating consistent bone healing and continued root development in humans, while developing techniques that increase the likelihood of achieving regeneration of the pulp-dentin complex.

Introduction

When pulp tissue becomes necrotic in immature teeth, the long-term prognosis is compromised. Treatment of these teeth presents many challenges, including difficulties in cleaning and shaping large canals with blunderbuss apices, obturation of canals with open apices, and potential root fractures caused by thin and/or weakened root walls. The use of regenerative techniques holds the promise of recreating the pulp-dentin complex.

Therapeutic options for the immature tooth with a necrotic pulp include apexification and regeneration, revascularization, or revitalization. There has been a debate as to which term, revascularization, revitalization, or regeneration, is most appropriate to describe the outcome of procedures used to regenerate pulp tissue. The debate continues because of the lack of definitive evidence of the outcomes of the procedures. The term revascularization is more commonly associated with dental trauma literature and describes reestablishment of vascular supply to immature permanent teeth. Revitalization describes ingrowth of vital tissue that does not resemble the original lost tissue. Endodontic regeneration is the replacement of “damaged structures, including dentin and root structures, as well as cells of the pulp-dentin complex.” In this article, the term revitalization is used to encompass all potential outcomes.

Clinical outcomes

Early Outcomes

The attempt to revitalize teeth with necrotic pulp tissue is not new to endodontics. In 1961, Nygaard-Ostby and Hjortdal demonstrated the ingrowth of fibrous connective tissue and cementum in mature teeth with necrotic pulp tissue after instrumentation, interappointment disinfection with sulfathiazole and 4% formaldehyde, overinstrumentation beyond the apex to evoke bleeding, and obturation short of the apex with Kloroperka paste and a gutta-percha.

In 1974, Myers and Fountain reported that a majority of incisors with mature apices that were disinfected with NaOCl and then had the apical openings intentionally enlarged and filled with citrated whole blood or gel foam experienced “root resorption, which correlated with the presence of chronically inflamed granulation tissue.” In the same experimental protocol, canines with immature apices (as opposed to incisors with mature apices) had evidence of increased root length and calcified material in the canals.

In 1976, Nevins and colleagues showed “various forms of hard and soft connective tissue,” including “cementum, bone, and reparative dentin” lining the walls of the root canal in immature necrotic incisors of monkeys after the placement of a gel (containing collagen, calcium chloride, and dipotassium hydrogen phosphate) and short obturation with gutta-percha. Thus, findings from early case series and studies demonstrated the possibility of obtaining revitalization of a previously infected canal space, albeit with varied histologic outcomes.

Recent Outcomes

In the past decade there has been increased interest in regenerative endodontic procedures following published case reports describing clinical procedures for revitalizing necrotic immature teeth. Using the methods described in these case reports, many clinicians have demonstrated radiographic evidence of increased root length and root wall thickness. An example of this outcome is shown in Fig. 1 . The techniques (eg, single vs multiple appointment, type of irrigant, type of antibiotic paste, and type of pulp space barrier) and recall periods vary, but all follow the principles of canal disinfection, creation of an environment and scaffolding for stem cell ingrowth, and placement of a coronal seal. A summary of the recall periods and outcome findings is shown in Table 1 .

| References | Recall Period | Apical Pathosis Healed? (# of Teeth) | Root Lengthened? (# of Teeth) | Root Wall Thickening? (# of Teeth) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Iwaya et al, 2001 | 30 mo | Healed (1) | Yes (1) | Yes (1) |

| Banchs & Trope, 2004 | 2 y | Healed (1) | Yes (1) | Yes (1) |

| Chueh & Huang, 2006 | 7 mo–5 y | Healed (4) | Yes (4) | Yes (4) |

| Petrino, 2007 | 8 mo | Healed (1) | Yes (1) | Yes (1) |

| Thibodeau & Trope, 2007 | 12.5 mo | Healed (1) | Yes (1) | Yes (1) |

| Jung et al, 2008 | 1–5 y | Healed (8) Reduced (1) |

Yes (7) Questionable (2) |

Yes (9) |

| Cotti et al, 2008 | 30 mo | Healed (1) | Yes (1) | Yes (1) |

| Shah et al, 2008 | 6 mo–3.5 y | Healed (4) Reduced (5) |

Unable to determine (9) | Unable to determine (9) |

| Chueh et al, 2009 | 6–108 mo | Healed (23) | Continued root development (23) | Continued root development (23) |

| Ding et al, 2009 | ≥1 y | Healed (3) Dropped out (6) Lost to recall (3) |

Complete root development with closed apex (3) | Complete root development with closed apex (3) |

| Reynolds et al, 2009 | 18 mo | Healed (2) | None (2) | Yes (2) |

| Shin et al, 2009 | 19 mo | Healed | Yes (1) | Yes (1) |

| Thibodeau, 2009 | 16 mo | Healed | Yes (1) | Yes (1) |

| Kim et al, 2010 | 8 mo | Healed (1) | Yes (1) | Yes (1) |

| Petrino et al, 2010 | 9–12 mo | Healed (1) | Yes (2) No (4) |

Yes (2) No (4) |

| Cehreli et al, 2011 | 9–10 mo | Healed (6) | Yes (6) | Yes (6) |

| Nosrat et al, 2011 | 15–18 mo | Healed (2) | None (2) | Yes (2) |

| Torabinejad & Turman, 2011 | 5.5 mo | Healed | Unable to determine (1) | Yes (1) |

| Lenzi & Trope, 2012 | 21 mo | Healed (2) | Unable to determine (2) | Yes (1) No (1) |

There are several challenges in interpreting the outcomes of case series and case report outcomes. These challenges include significant variability in technique and recall period, a potential bias of only successful cases being reported, and the lack of consistent radiographic angulation between pretreatment and follow-up radiographs. Case reports and case series do, however, demonstrate that regenerative endodontic techniques can result in healing apical pathosis and root development. The American Association of Endodontists maintains a database of revitalization cases with follow-up radiographs. Analysis of this data adds to the existing case reports/series and assists in the development of controlled clinical trials.

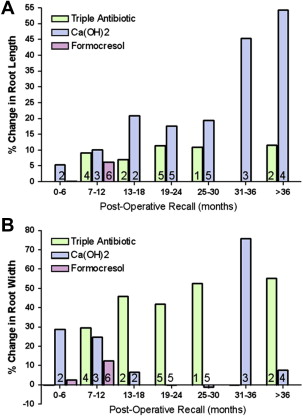

Two recent reports have attempted to account for variability in radiographic angulation by using a geometric imaging program to minimize potential differences in angulation between the preoperative and recall images. The standardization of radiographic images enabled the calculation of continued development of root length and dentin wall thickness. Bose and colleagues compared outcomes from teeth that were medicated with Ca(OH) 2 with triple antibiotic paste and with formocresol. Their results showed that teeth treated with triple antibiotic paste and Ca(OH) 2 had significantly greater increases in root length than the control teeth (apexification or NSRCT) and that triple antibiotic paste produced significantly greater differences in root wall thickness than either the Ca(OH) 2 or formocresol groups. The investigators also found that the percentage change in root length and root width increased over time ( Fig. 2 ). Cehreli and colleagues evaluated the changes in root length and width in 6 immature necrotic permanent first molars that were treated by a revitalization protocol using 2.5% NaOCl irrigation and medication and with calcium hydroxide. The investigators found, after 9 to 10 months follow-up, progressive thickening of dentinal walls (15%–38%) and increased root length (2%–18%) in all teeth.

These case reports and case series emphasize the importance of follow-up, including recording symptoms, radiographs, and clinical tests. Because of the variability in recall, it is difficult to establish time frames in which practitioners may expect to see radiographic changes. This information is important because it can help in assessing if and when alternative treatments (ie, apexification, traditional nonsurgical root canal therapy, or extraction) may be necessary. Chueh and colleagues did attempt to determine the timing of radiographic changes. In this case series, 23 necrotic immature permanent teeth were irrigated with 2.6% NaOCl and treated with either short- (<3 months) or long-term treatment (<3 months) Ca(OH) 2 paste medication. The investigators found radiographic evidence of apical bone healing in 3 to 21 months (mean = 8 months), and radiographic evidence of root development in 10 to 29 months (mean = 16 months). These results suggest that if radiographic evidence of healing and root development has not occurred within approximately 2 years after the completion of treatment, alternative treatments may be necessary.

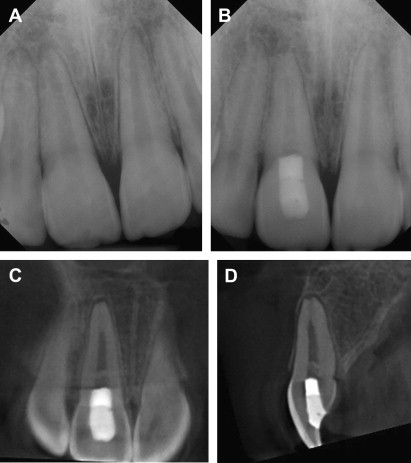

Radiographic assessment can be enhanced with the use of cone beam computed tomography (CBCT) because it reveals views of the tooth and surrounding bone not seen with periapical radiographs. This technique was demonstrated in a recent case report of adjacent incisors, 1 of which was revitalized successfully and the other that had radiographic signs of failed treatment. An example of the additional radiographic information (eg, lateral view) that can be seen in CBCT images is shown in Fig. 3 . Given the increased radiation exposure associated with CBCT, it is important to weigh the benefits of the increased visualization with the risks of radiation exposure and minimize the field of view as much a possible. As with follow-up after other endodontic procedures, if there are persistent symptoms, recurrence of symptoms, increased apical radiolucency, and/or radiographic evidence of root resorption at any point, alternative treatment should be considered.

In addition to radiographic evidence of healing apical bone and continued root development, some case reports and case series have demonstrated positive responses to cold and/or electric pulp tests in teeth that underwent revitalization procedures. The positive response to pulp tests may be an indication of regeneration of innervation in the canal space. The lack of a pulp response, however, does not necessarily indicate a lack of vitality. The case series in which there was no response to pulp testing, there was radiographic evidence of continued root development, indicating the presence of vital tissue in the canal space. Future developments in assessing pulp vitality will allow for a more accurate assessment of treatment success.

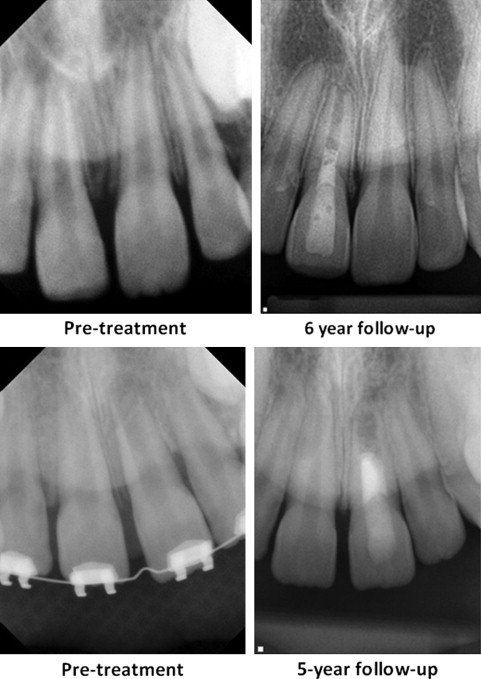

The healing of the apical bone and resolution of symptoms, in the absence of continued root growth, may be an acceptable outcome for many patients and practitioners. Survival, or retention of the treated tooth, is an accepted outcome measure. Given that loss of a permanent tooth before completion of alveolar bone development can lead to atrophy of the alveolar ridge, thus potentially compromising future implant replacement, a reasonable goal of revitalization procedures should be retention of the treated tooth until completion of alveolar ridge development, even in the absence of continued root development. Examples of tooth retention without continued root development are shown in Fig. 4 .

Clinical outcomes

Early Outcomes

The attempt to revitalize teeth with necrotic pulp tissue is not new to endodontics. In 1961, Nygaard-Ostby and Hjortdal demonstrated the ingrowth of fibrous connective tissue and cementum in mature teeth with necrotic pulp tissue after instrumentation, interappointment disinfection with sulfathiazole and 4% formaldehyde, overinstrumentation beyond the apex to evoke bleeding, and obturation short of the apex with Kloroperka paste and a gutta-percha.

In 1974, Myers and Fountain reported that a majority of incisors with mature apices that were disinfected with NaOCl and then had the apical openings intentionally enlarged and filled with citrated whole blood or gel foam experienced “root resorption, which correlated with the presence of chronically inflamed granulation tissue.” In the same experimental protocol, canines with immature apices (as opposed to incisors with mature apices) had evidence of increased root length and calcified material in the canals.

In 1976, Nevins and colleagues showed “various forms of hard and soft connective tissue,” including “cementum, bone, and reparative dentin” lining the walls of the root canal in immature necrotic incisors of monkeys after the placement of a gel (containing collagen, calcium chloride, and dipotassium hydrogen phosphate) and short obturation with gutta-percha. Thus, findings from early case series and studies demonstrated the possibility of obtaining revitalization of a previously infected canal space, albeit with varied histologic outcomes.

Recent Outcomes

In the past decade there has been increased interest in regenerative endodontic procedures following published case reports describing clinical procedures for revitalizing necrotic immature teeth. Using the methods described in these case reports, many clinicians have demonstrated radiographic evidence of increased root length and root wall thickness. An example of this outcome is shown in Fig. 1 . The techniques (eg, single vs multiple appointment, type of irrigant, type of antibiotic paste, and type of pulp space barrier) and recall periods vary, but all follow the principles of canal disinfection, creation of an environment and scaffolding for stem cell ingrowth, and placement of a coronal seal. A summary of the recall periods and outcome findings is shown in Table 1 .