This article describes the complex orthodontic treatment of a 22-year-old patient with Duchenne muscular dystrophy and macroglossia. His orthodontic treatment hinged on providing proper informed consent and management of the malocclusion with glossectomy, extractions, fixed appliances, and elastics. Challenges to traditional treatment are outlined, and compromises to both process and outcome are discussed from an informed consent point of view because of the serious risks involved. The treatment objectives were met, and the outcome was considered a success.

The purpose of this article is to describe the orthodontic treatment of a 22-year-old man with Duchenne muscular dystrophy and macroglossia. He used a power wheelchair that he controlled with a joystick, and some aspects of diagnosis and treatment were adapted to address his needs and abilities. I report here the treatment we provided, including the compromises that were made and the problems that arose. I discuss the patient’s treatment based on his wishes and desires from an informed consent perspective and outline our limitations to “standard” orthodontic care delivery because of the unique nature of Duchenne muscular dystrophy.

Diagnosis and etiology

A 22-year-old man came to the University of Minnesota faculty practice with a chief complaint of difficulty chewing; he reported that he was unable to bite into or chew his food effectively. He conveyed great frustration with this quality-of-life limitation to functional chewing. He was referred by his pediatric dentist and had no evidence of tooth decay or periodontal disease. He was accompanied by his mother and a caregiver. His past medical history was remarkable for Duchenne muscular dystrophy and an allergy to Augmentin. He did not have a tracheostomy tube. He was unable to voluntarily lift his arms and relied on caregivers for oral hygiene. The clinical examination and initial photographic montage ( Fig 1 ) in full occlusion showed generalized excessive buccal crown torque with an anterior open bite of 8 to 10 mm and a posterior open bite of 0 to 12 mm. There was generalized mandibular spacing and an estimated 50% Class II molar relationship. He displayed signs of massive macroglossia and a single-point contact in maximum intercuspal position. He had only 50% incisor display on smile, and there was not a detectable centric relation to centric occlusion shift or discrepancy.

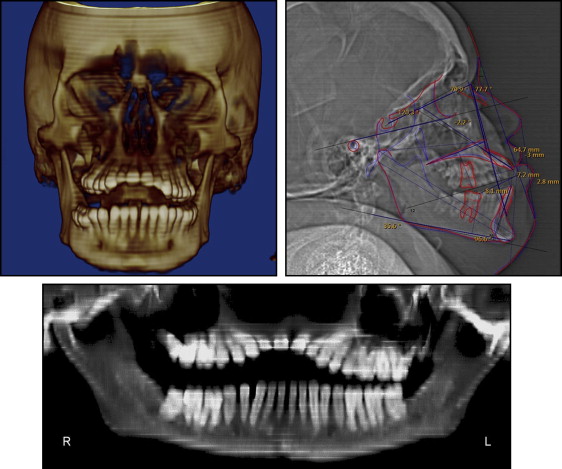

A medical computed tomograhpy scan was obtained from Suburban Imaging in Minneapolis. DICOM data were extracted and read at the University of Minnesota with help from an oral radiologist using volumetric, panoramic, and cephalometric reconstructions ( Fig 2 ). These added to our problem list. We discovered an impacted maxillary right third molar and a supernumerary maxillary left impacted paramolar. His maxillary incisors were proclined with a U1-SN measurement of 120.3°.

Skeletally, he had discrepant maxillomandbular measurements with an ANB angle of −2.2° and a Wits value of 7.7 mm. With his degree of generalized proclination throughout both arches and related mandibular opening rotation, these anteroposterior skeletal measurements were given minimal diagnostic weight; the overall assessment from all records, including the clinical examination, suggested that his skeletal anteroposterior position was Class I.

The fact that he was occluding only on the lingual cusps of the left second molars (single-point contact) in addition to the generalized excessive buccal crown torque and mandibular generalized spacing led to the conclusion that these findings were sequellae from the macroglossia.

Treatment objectives

The treatment goals in prioritized order were to (1) extract all third molars and the supernumerary paramolar, (2) reduce his massive tongue volume, (3) establish a functional occlusion, (4) close his anterior and posterior open bites and generalized spacing, and (5) increase his incisor display on smile.

Treatment objectives

The treatment goals in prioritized order were to (1) extract all third molars and the supernumerary paramolar, (2) reduce his massive tongue volume, (3) establish a functional occlusion, (4) close his anterior and posterior open bites and generalized spacing, and (5) increase his incisor display on smile.

Treatment alternatives

The following treatment options were discussed with the patient.

- 1.

No treatment.

- 2.

Glossectomy with extraction of the supernumerary maxillary left molar and all third molars, wait 6 months for natural uprighting of the dentition, and reassess the patient for either premolar extractions or a nonextraction treatment plan; oral hygiene instructions for the caregivers; bond fixed appliances; level and align the arches using elastics to manage the severe proclination; and detail and finish occlusion until the objectives were met.

Although numerous glossectomy techniques have been described, the keyhole technique with anterior wedge reduction is the most common. To establish a functional occlusion and close his bite, we intended to add simple crown tipping and lingual crown torque in a generalized fashion in both arches. With incisor uprighting, both bite closure and increased incisor display are known to occur through relative extrusion. Some bite closure can be expected through molar uprighting as well; as the palatal cusps are tipped lingually, elimination of cuspal interferences should lead to bite closure through autorotation of the mandible. The mandibular interproximal spaces were to be closed with elastomeric chains.

The patient and his parents were present during the informed consent and consultation appointment in March 2009. His chief concern was confirmed, his orthodontic findings were fully disclosed, his medical history was reviewed, and we discussed the above options for correction, including no treatment. We explained that although orthodontic treatment would not be stable unless the glossectomy procedure was performed, he was under no obligation to have treatment. Because of his strong commitment to improve his occlusion, he was sent for an evaluation for this glossectomy procedure and given a recommendation that he ask his other doctors about the inherent risks of the surgery in light of his preexisting medical condition. He was informed that his surgeon and medical doctor would be in the best positions to comment on these risks. The patient, under his own free will and with support from his parents, decided to go forward with the second treatment alternative above.

Treatment progress

In June 2009, the third molars were extracted, including the impacted supernumerary molar, and a keyhole wedge reduction glossectomy ( Fig 3 ) was performed with the patient under general anesthesia. During the surgery, a tracheostomy procedure was also performed and a tracheostomy tube was placed. He spent approximately 1 month in a care facility after the surgery.

The patient returned to the University of Minnesota faculty practice for photos in January 2010, 7 months postsurgery, with a tracheostomy tube in place. The clinical examination showed that his 8-mm anterior open bite closed spontaneously by approximately 6 to 7 mm, and his 12-mm posterior open bite on the right side closed by approximately 3 to 6 mm ( Fig 4 ). His hygiene was poor. The patient indicated that he still wanted braces for better chewing function, even though his chewing ability was improved from the surgery. A nonextraction plan was chosen for 2 reasons: (1) the dramatic bite closure observed in the 7 months immediately after his surgery and (2) the clinical estimation that our treatment goals could be achieved without extractions.

In April 2010 he demonstrated dramatically improved hygiene. Victory series (3M Unitek, Monrovia, California) 0.022-in slot Miniature Twin brackets were placed from first molar to first molar in both arches in addition to lingual attachments on the maxillary first molars and second premolars. Nickel-titanium archwires (0.014 in) were placed, and the patient was instructed to wear vertical Class III elastics to maintain positive overjet and “over the arch” cross elastics to upright and tip the mandibular molars ( Fig 5 ). In June 2010, 0.017 × 0.025-in nickel-titanium archwires and transpalatal elastics along with continued cross elastics were placed for improved torque. In July 2010, his elastics were altered to mandibular transarch and vertical elastics. In August 2010, 0.018-in nickel-titanium archwires were completely engaged into the Miniature Twin slots to derotate his mandibular premolars. Dramatically improved bite closure and excellent uprighting were observed, so the elastic scheme was altered again for continued bite closure and molar buccal crown tipping. In October 2010, a 0.021 × 0.025-in nickel-titanium archwire was placed for finishing torque expression in his maxillary arch. A 0.016-in stainless steel archwire was placed to level his mandibular curve of Spee. In December 2010, 0.017 × 0.025-in maxillary and 0.016 × 0.022-in mandibular stainless steel wires were placed to finish leveling and continue torque expression. The use of vertical elastics dramatically improved his occlusion and provided a positive overbite.