The maxillary central incisor is the tooth most often affected by trauma, especially in the age range of 7 to 10 years, when high-impact sports are prevalent. The options for conservative treatment should be prioritized in these patients, aiming to achieve a biologic response that might provide continuity of growth of the alveolus, to provide functional and esthetic development of the affected region. This case report describes a patient with a history of trauma during the deciduous dentition with consequent intrusion, root dilaceration, and retention of the maxillary left central incisor. The treatment involved extraction of the traumatized tooth and mesial movement of the lateral incisor and posterior segments.

Dentists must occasionally treat patients with a history of trauma to the maxillary anterior teeth. According to Zachrisson, the maxillary central incisor is the tooth most often affected by trauma, especially from 7 to 10 years of age. These years are considered to have the highest risk, because of the high-impact sports that children play during this period.

The high prevalence of trauma during the deciduous dentition and the close anatomic proximity to the permanent tooth buds might explain the high frequency of alterations that occur in developing permanent teeth. As mentioned by Andreasen and Ravn, Andreasen, and Andreasen and Andreasen, permanent tooth damage can occur simultaneously with the trauma, because of the direct impact of the deciduous tooth root on the developing permanent tooth bud or later as a consequence of posttraumatic complications. Mattison et al believed that the trauma might result in minor alterations in enamel mineralization or produce displacement of the permanent tooth bud. The latter consequence could cause impaction, crown or root dilaceration, or both, ultimately leading to severe root resorption and tooth loss.

When trauma causes the loss of at least 1 maxillary central incisor, 4 treatment options have been proposed in the literature: autotransplantation, prosthetic replacement, replacement with endosseous implants, and space closure. Selection of the best option depends on several factors such as the patient’s age, skeletal and facial patterns, sagittal relationship between the dental arches, root integrity, coronal dimensions of the lateral incisors, and patient compliance.

In this article, we describe the treatment of a patient with a history of trauma during the deciduous dentition with subsequent intrusion, root dilaceration, and retention of the maxillary left central incisor. The treatment involved extraction of this tooth with biological replacement by mesial movement of the lateral incisor and posterior segments.

Diagnosis and etiology

A girl, aged 11 years 7 months, came to our orthodontic clinic with the chief complaint of a missing maxillary left central incisor. During the anamnesis, the mother reported a history of trauma during the deciduous dentition. The extraoral photographs showed a harmonious face with proportional facial thirds and spontaneous lip seal. The profile view exhibited a good facial contour between the nose, lips, and chin, with balanced nasolabial and mentolabial angles ( Fig 1 ).

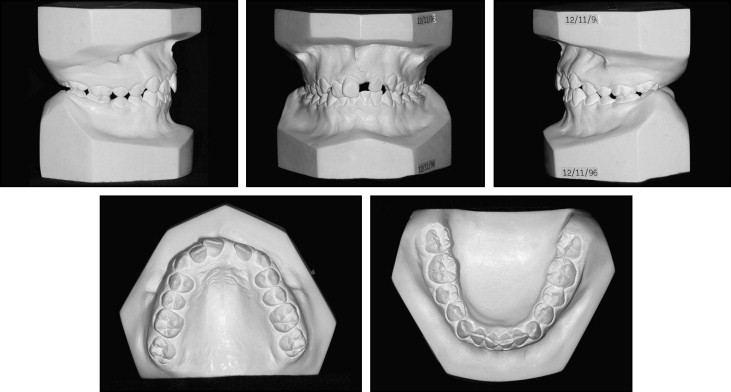

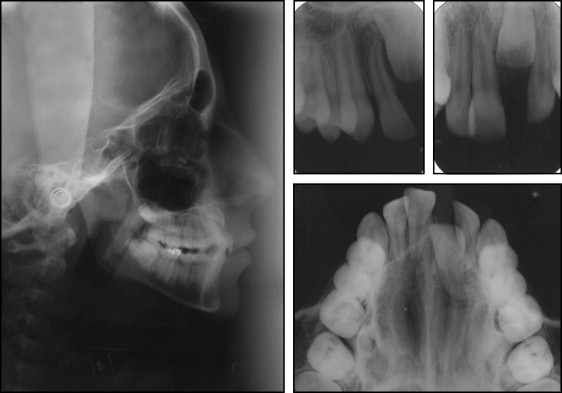

The intraoral examination ( Figs 1 and 2 ) showed an Angle Class II relationship for both the molars and the canines. The mesial aspect of the maxillary right central incisor was coincident with the facial midline, despite the clinical absence of the maxillary left central incisor. The mesial inclination of the maxillary left lateral incisor was invading the space of the unerupted adjacent tooth and alteration in the gingival contour of the maxillary anterior teeth. Overbite was 50%, and overjet was 3 mm.

The panoramic radiograph showed the unerupted maxillary left central incisor, positioned high in the alveolar process, with root dilaceration at the apical third ( Fig 3 ).

Treatment goals

The treatment goals were to achieve a functional occlusion, establish satisfactory esthetics by replacing the maxillary left central incisor by mesial movement of the maxillary left lateral incisor, correct the occlusion by extracting the maxillary right first premolar to create a Class I canine relationship and a Class II molar relationship, and improve the overbite, overjet, and gingival contour of the teeth in the maxillary anterior region.

Treatment goals

The treatment goals were to achieve a functional occlusion, establish satisfactory esthetics by replacing the maxillary left central incisor by mesial movement of the maxillary left lateral incisor, correct the occlusion by extracting the maxillary right first premolar to create a Class I canine relationship and a Class II molar relationship, and improve the overbite, overjet, and gingival contour of the teeth in the maxillary anterior region.

Treatment options

The following treatment options were suggested.

- 1.

Space opening followed by surgical access to bond an orthodontic attachment on the maxillary left central incisor and erupt the tooth orthodontically.

- 2.

Space opening, extraction of the maxillary left central incisor, and autotransplantation of the maxillary right first premolar.

- 3.

Allow the maxillary left central incisor to remain submerged, open the space, eventually extract the maxillary left central incisor, and place an implant after completion of skeletal growth.

- 4.

Extract the maxillary left central incisor with space closure and mesial movement of the maxillary left lateral incisor.

The decision for space closure was chosen because of the mesial positioning of the maxillary left lateral incisor, the marked Class II relationship on the left side, and the potential to maintain the bone and the periodontium by the mesial movement of the adjacent teeth.

Treatment progress

After explaining the options, we decided on space closure and mesial movement of the maxillary left lateral incisor and posterior segments. Initially, we placed bands on the maxillary and mandibular first molars and bonded brackets on the remaining teeth. The bracket on the maxillary left lateral incisor was bonded with a slight mesio-cervical inclination to allow mesial movement of the root. The patient was referred for extraction of the maxillary right first premolar and left central incisor soon after placement of the maxillary appliances.

Alignment and leveling were performed by using 0.014-, 0.016-, and 0.018-in nickel-titanium archwires, followed by 0.018- and 0.020-in stainless steel archwires. The canine relationship on the right side was corrected by distal movement of the maxillary right canine with elastomeric chains. Open coils were placed between the maxillary left lateral incisor and the canine, and between the maxillary left canine and the first premolar for anterior space closure, combined with Class II elastics on the right side and Class III elastics on the left side. After closure of the anterior space, the residual space mesial to the molar on the left side was reduced by using chain elastics and a protraction facemask.

A lingual arch was placed in the mandibular arch, followed by interproximal stripping of the mandibular anterior teeth. Alignment and leveling were then performed with 0.014-, 0.016-, and 0.018-in nickel-titanium archwires and a 0.020-in stainless steel archwire. The treatment was finalized by using 0.019 × 0.025-in rectangular stainless steel archwires.

After treatment completion, the maxillary appliances were removed, and the patient was referred for esthetic restoration of the maxillary anterior teeth with composite resin. Since we believed that gingival recontouring would be required after reconstruction of the maxillary left lateral incisor, gingival surgery was not immediately recommended. The gingival margin level would change after the tooth was recontoured.

Treatment results

The treatment response was considered excellent because of maintenance of facial harmony and good dental leveling with an acceptable gingival contour ( Fig 4 ). Class II molar and Class I canine relationships were maintained on both sides. On the left side, occlusal adjustment was performed by grinding the palatal cusp of the maxillary left first premolar that functioned as a canine. The incisal edge and the buccal convexity of the maxillary left canine were reduced to favor the function of a lateral incisor. The patient was referred for restoration of the maxillary left lateral incisor, by adding composite resin on the mesial, distal, and incisal aspects to achieve the esthetic appearance of the contralateral maxillary right central incisor ( Figs 4 and 5 ).