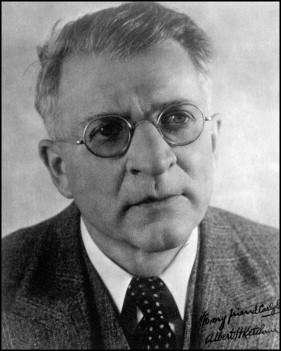

One of the last of a breed of strong, willful, and purposeful men who left an indelible mark on the early history of orthodontics was Albert H. Ketcham. Born in Whiting, Vermont, on August 3, 1870, he was educated at the Vermont Academy and Boston Dental School, where he received his dental degree in 1892. In 1894 he was married in Boston to Mary E. Hickson, who bore him two children—a son, Arthur C., and a daughter, May G. A second marriage, to Flora B. Smith in Denver, Colorado, in 1923, brought him much happiness in his rather troubled and turbulent later years.

Dr. Ketcham’s career as a dentist received an early setback when tuberculosis almost claimed him as a victim, and he came to Colorado at the turn of the century more dead than alive. He grew to love the West, not only because it brought him back to health but also because it offered wide-open spaces in which he had room to roam and to engage in the hunting and fishing that he loved. His indomitable will speeded his recovery to where he could resume practice in a limited say. He fitted an office in Meeker, Colorado, with a saddle rigged as a dental chair to make his cowboy patients feels more at ease.

As his recovery became more complete, his creative energy demanded fuller expression. He moved to Denver where for a while he specialized in periodontics. This offered no great challenge to him, however. He began to realize that the field of orthodontics held greater potential for health services of unlimited challenge in an age group that could appreciate them for a whole lifetime. Therefore, in 1902, he became a student of Edward H. Angle, and the profession of orthodontics received one of its most dedicated leaders.

Although he was dogged by more than his share of physical handicaps, Dr. Ketcham was essentially strong physically. His large, raw-boned frame was topped by a mass of unruly hair that seemed to give him a rough-and-ready schoolboy alertness. His slow, studied speech and his eyes peering through thick lenses bespoke of gentleness, thoughtfulness, and understanding. His uneven, somewhat lurching, walk hinted at uncompromising but unheeded pains and made his actions pointedly purposeful. Thus, he instilled confidence in those who met him. To him, friendships were highly prized but not altogether priceless. He made enemies by expressing his thoughts clearly and often bluntly. His opinions on any question were always arrived at by much reading, discussion, and serious thinking, and from these opinions he did not retreat readily. His was an investigative mind that probed deeply into new or controversial problems, and so, although he and Dr. Angle traveled the same path in the same direction, they never could travel serenely side by side. Each did his own thinking.

This was the man who served as president of the American Society of Orthodontists, as the A.A.O. was then known, in the 1928-1929 term. Under his leadership, much was accomplished to strengthen that organization as a national body. At the 1929 meeting in Estes Park, Colorado, Dr. Ketcham called attention to the fact that there were members of the American Society of Orthodontists who were not members of the American Dental Association. In order to remedy this condition, the Society passed a resolution requesting all the members of the A.S.O. to become members of their local, state, and national dental societies. The requirements for active membership in the A.S.O. were changed, making membership in the American Dental Association compulsory. Also, at Dr. Ketcham’s suggestion, the Education Committee was established as a standing committee of five members, each serving for five years, and a Committee on Nomenclature was created.

Probably the project closest to his heart, and one on which he expended much of his energy, was the formation of the American Board of Orthodontics. Physician friends who were members of the American Board of Ophthalmology (the first medical certifying board) and the American Board of Otolaryngology gave him many of the ideas that formed the basic pattern of the American Board of Orthodontics. Because he felt that orthodontics needed a certifying board, he recommended its formation at the Estes Park meeting, and this recommendation was immediately and unanimously adopted by the Society. The members of the first Board were nominated by the Executive Committee and elected by the Society. The American Board of Orthodontics was incorporated under the laws of the State of Illinois in 1930, and Dr. Ketcham served as its first president.

Editorializing on the Estes Park meeting of the American Society of Orthodontists, Martin Dewey stated: “It is our belief that the meeting of the A.S.O. under the guidance of Dr. Ketcham has accomplished the most constructive work in the history of the Society.”

Albert Ketcham loved and was completely devoted to his profession. The last paragraph of his president’s address makes this clear. He said: “In closing, let me say that we may make our lives greatly useful in our chosen specialty, that the knowledge of orthodontia may advance apace and be the dominant factor in the welfare of humanity that it can and should be. Then the many and far-reaching benefits of orthodontia may be enjoyed by the great host of children to whom it will be such a priceless boon.”

His scientific contributions were many and varied, and all were aimed at the betterment of his profession. His case reports of both failures and successes were scrupulously presented in the hope that they might in some way enlarge the scope of orthodontic possibilities. He was an idealist, and it pained him to recognize limitations. Yet, his most exhaustive work tended at times to make him seek compromise. This was his extensive investigation on apical root resorption of vital permanent teeth. His two articles reporting this study stunned the orthodontic profession and did much to lend greater emphasis to the biologic aspect in orthodontic thinking.

Spurred by his findings, he instigated a research program at the Hooper Foundation for Medical Research at the University of California with Dr. John A. Marshall in charge. The necessary operating funds were raised by voluntary contributions from members of the American Society of Orthodontists.

As one of the recognized leaders in his field, he was besieged by requests from men seeking orthodontic education to serve as a preceptor. Through the years many men came under his strict supervision in his office. As a teacher, he was characteristically thorough, giving time that seemed unavailable to instill in his students proper procedure and concept. He never felt that his duties as an instructor had ended, for he corresponded voluminously with those who left his direct supervision. He labored, sometimes beyond reason, to effect exact wording in his letters so that there would be no doubt as to his thoughts.

When his waking hours were not taken up with the serious business of orthodontics, they were plunged deeply into his hobbies of hunting, fishing, and general enjoyment of his Rocky Mountain high country. Since he could never have been accused of having any semblance of a split personality, his behavior away from the office was also ever meticulous. As the hunting or fishing season approached, he laid plans and checked equipment carefully. For him, time, even leisure time, was too precious to be allowed to escape without taking the fullest advantage of it.

His favorite summertime retreat was a rustic cabin high in the hills not too far from Denver. Here, in the cool, pine-scented air that separated the clear blue sky from the equally clear blue waters of his trout haven known as Lake Edith, he could relax completely. He could relax in the swivel chair that he had mounted in his boat as he expertly cast a fly to where he was sure a hungry trout was waiting for it. The trout must have liked the flies he used or the way he presented them, for he consistently came back with more than the others who attempted to lure the wary creatures.

Driving his uninitiated lowland friends to Lake Edith, which was at an altitude of over 10,000 feet, allowed him to exercise a mild form of practical joking that he enjoyed. The narrow, precarious roads with sides that dropped vertically several hundred feet usually terrorized his passengers. He delighted in adding to this terror by warning them that they all might have to help push the car up the last mile. This threat seemed about to become a reality moments before the car finally scrambled from its precipitous roadway and rolled peacefully into the hushed stillness of what he considered God’s country.

Dr. Ketcham had friends from all walks of life—from machinists who helped him devise special equipment at his office to college professors with whom he often collaborated on varied subjects, and from cowboys to artists. People remembered him even though sometimes they were in contact with him for only a short time. Dr. H. C. Pollock, editor of the American Journal of Orthodontics , tells of having lunch recently with Dr. R. C. Seibert who told him of a pack trip he had made fifty years ago into the remote roadless Mesa Verde country of Colorado. There he met a Denver dentist whose name he could not recall, but he remembered that he wore thick-lensed glasses, was a meticulous chap, and was tremendously interested in digging around the ancient ruins. Dr. Pollock knew immediately that the man in question could be none other than Albert Ketcham, as proved to be the case.

This man who was so unforgettable had two great loves. First and foremost was his chosen profession of orthodontics, and second was hunting and fishing. In each he was an authority and an expert. Despite physical handicaps that would have discouraged lesser men, he expended more meaningful energy in each of these than did most of his more robust colleagues. This was Dr. Albert H. Ketcham, who died on Dec. 5, 1935.

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses