In this case report, we present the orthodontic and surgical management of an 18-year-old girl who had a severe craniofacial deformity, including maxillary prognathism, vertical maxillary excess (gummy smile), mandibular retrognathism, receding chin, and facial asymmetry caused by unilateral temporomandibular joint ankylosis. For correction of the facial asymmetry, the patient’s right mandibular ramus and body were lengthened via distraction osteogenesis after 5 months of preoperative orthodontic therapy. Subsequently, extraction of 4 first premolars, bimaxillary anterior segmental osteotomy, and genioplasty were simultaneously performed in the second-stage operation to correct the skeletal deformities in the sagittal and vertical planes. Postoperative orthodontic treatment completed the final occlusal adjustment. The total active treatment period lasted approximately 30 months. The clinical results show that the patient’s facial esthetics were significantly improved with minimal surgical invasion and distress, and a desirable occlusion was achieved. These pleasing results were maintained during the 5-year follow-up.

Highlights

- •

Facial asymmetry due to unilateral TMJ ankylosis was corrected by distraction osteogenesis.

- •

Intermaxillary elastic traction may help to correct the occlusal plane.

- •

Bimaxillary osteotomy with extractions was a less invasive treatment option.

- •

Multidiscipline cooperation should be part of the treatment plan.

Temporomandibular joint (TMJ) ankylosis is a pathogenic condition after damage to the mandibular condyle. When this event takes place in the unilateral condyle during a patient’s active growth stage, the normal growth balance of the mandibular ramus on both sides may be disrupted even though the mobility of the mandible is recovered in childhood via TMJ surgery. TMJ ankylosis can ultimately result in severe mandibular malformations in adulthood, such as mandibular deviation and retrognathism. To address these single-jaw malformations, several methods are available, such as distraction osteogenesis and mandibular sagittal split osteotomy, which may be considered as easy tasks of correction by contemporary surgeons. However, when mandibular deficiencies are compounded with maxillary deformities such as maxillary vertical excess and prognathism, it becomes a challenge for clinicians to treat patients with such problems because the correction of double-jaw deformities may require more challenging surgical techniques or a combination of multiple surgical modalities for improved facial esthetics. Although the operative modalities for various deformities in the maxilla and the mandible have become safer and more reliable with the development of surgical skills and knowledge, multiple-stage and multiple-site surgeries still may put patients at great risk for intraoperative and postoperative complications, such as wound healing, nerve injury, and hemorrhage. Furthermore, because of the involvement of orthognathic surgeries in the oral region, patients often suffer the limitation of stomatognathic functions after an operation, leading to a compromised quality of life. Therefore, a patient-centered outcome has recently drawn increasing attention in modern dentistry. Not only the treatment result but also the treatment duration and the possible physical and psychological distress caused by surgeries should be considered when making a treatment plan.

In this case report, we describe the orthodontic and surgical treatment of a patient with a severe craniofacial deformity due to unilateral TMJ ankylosis. To correct the facial asymmetry, maxillary prognathism, gummy smile, mandibular retrognathism, and receding chin, distraction osteogenesis, extraction of 4 first premolars, bimaxillary anterior segmental osteotomy, and genioplasty were sequentially performed on the patient. The detailed postoperative orthodontic treatment and 5-year follow-up records are also described in this article.

Diagnosis and etiology

A young woman, 18 years old, visited the orthodontic department at the Stomatological Hospital of Chongqing Medical University in China with chief complaints of facial asymmetry, mandibular retrognathism, maxillary prognathism, and gummy smile. Her case history indicated that at 9 years old, she underwent gap arthroplasty on the right TMJ in another medical institution because of trauma-induced TMJ ankylosis. After surgery, she had a normal mouth opening, but the secondary dentofacial deformity developed during her growth period because of the damage of the condylar growth center on the ankylosed side.

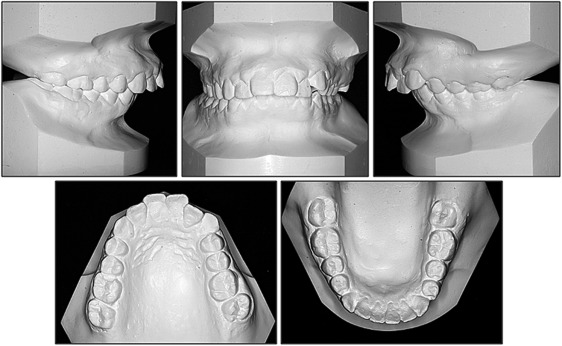

As shown in Figure 1 , the facial photographs showed an obvious asymmetric face and a severely convex profile. The chin point was severely deviated (approximately 10 mm) to the right side relative to the craniofacial midline. Intraoral photographs showed a Class II malocclusion with a 10-mm overjet and a 7-mm overbite. Mild crowding was observed in both arches. The mandibular dental midline was shifted 5 mm toward the right. In agreement with the clinical examination, the cephalometric analysis demonstrated that the patient had a skeletal Class II jaw relationship with a retrognathic mandible and labially inclined mandibular incisors. The chin appeared deficient as well. Moreover, the angle of the mandible was underdeveloped. A panoramic radiograph showed irregularly shaped right condylar and coronoid processes, along with mandibular ramus hypoplasia on the right side and chin deviation. A caries lesion was found in the maxillary right first molar. Four third molars were still developing in the alveolar bones ( Figs 1-3 ; Table ).

| Group measurement | Initial measurements | Final measurements | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Value | Norm | SD | Value | Norm | SD | |

| Maxilla to cranial base | ||||||

| SNA (°) | 83 | 82 | 3.5 | 79.2 | 82 | 3.5 |

| Mandible to cranial base | ||||||

| SNB (°) | 67.7 | 77.7 | 3.2 | 68.8 | 77.7 | 3.2 |

| SN-MP (°) | 49.7 | 32.9 | 5.2 | 46.1 | 32.9 | 5.2 |

| FMA (MP-FH) (°) | 46.6 | 27.9 | 4.7 | 41.6 | 27.9 | 4.7 |

| Maxillomandibular relationship | ||||||

| ANB (°) | 15.6 | 4.0 | 1.8 | 10.3 | 4.0 | 1.8 |

| Maxillary dentition | ||||||

| U1-NA (mm) | 4.1 | 4.3 | 2.7 | 0.5 | 4.3 | 2.7 |

| U1-SN (°) | 102.0 | 103.8 | 5.5 | 86.1 | 103.8 | 5.5 |

| Mandibular dentition | ||||||

| L1-NB (mm) | 17.7 | 4.0 | 1.8 | 13.5 | 4.0 | 1.8 |

| L1-MP (°) | 110.5 | 95.0 | 7.0 | 105.4 | 95.0 | 7.0 |

| Soft tissue | ||||||

| Lower lip to E-plane (mm) | 9.1 | 2.0 | 2.0 | 1.8 | 2.0 | 2.0 |

| Upper lip to E-plane (mm) | 8.8 | 1.0 | 2.0 | 0.3 | 1.0 | 2.0 |

Treatment objectives

To address the patient’s chief complaints, the treatment objectives were as follows: (1) correct the asymmetric facial appearance, (2) correct the convex facial profile and moderate gummy smile, (3) resolve the dental crowding, (4) establish normal overbite and overjet, and (5) achieve an ideal occlusion.

Treatment objectives

To address the patient’s chief complaints, the treatment objectives were as follows: (1) correct the asymmetric facial appearance, (2) correct the convex facial profile and moderate gummy smile, (3) resolve the dental crowding, (4) establish normal overbite and overjet, and (5) achieve an ideal occlusion.

Treatment alternatives

The possible options for the treatment of this patient were (1) orthodontic retraction of anterior teeth with extraction of the 4 first premolars, (2) bilateral mandibular sagittal split osteotomy, (3) distraction osteogenesis, (4) LeFort I osteotomy, (5) anterior segmental surgery with extraction of the 4 first premolars, and (6) genioplasty.

The first option is a camouflage treatment, which is indicated for growing patients with functional or minor skeletal Class II malocclusion. This alternative could achieve occlusal correction, but there would be no improvement in the severe skeletal disharmony such as the asymmetric face and the retrognathic mandible.

In the coronal plane, bilateral mandibular sagittal split osteotomy and unilateral distraction osteogenesis have been reported for the surgical management of facial asymmetry. However, as far as postoperative stability is concerned, distraction osteogenesis has more advantages over bilateral mandibular sagittal split osteotomy for extensive lengthening of the mandibular ramus (10 mm or more). Therefore, distraction osteogenesis was considered as the better choice because of the patient’s severe facial asymmetry.

After correction of facial asymmetry by unilateral distraction osteogenesis, the second stage was to treat the maxillary skeletal deformity in the sagittal and vertical planes. Either LeFort I osteotomy or anterior segmental surgery can be used to correct maxillary prognathism with a gummy smile. However, since there are greater surgical risks and medical costs for the LeFort I osteotomy procedure, the anterior segmental osteotomy of the maxilla with extraction of 2 maxillary premolars has been recommended to our patients. To retract proclined mandibular anterior teeth and allow sufficient setback of the anterior segment of the maxilla, we planned to simultaneously perform the same surgery in the mandible with extraction of 2 mandibular premolars. Compared with presurgical anteroposterior orthodontic decompensation, this strategy is believed to significantly reduce treatment duration. Also, for further improvement of esthetics in the facial profile, genioplasty, an additional plastic surgery, was concurrently scheduled in the second-stage surgery to reconstitute the chin prominence.

Overall, a systematic and staged orthognathic procedure was designed for our patient; it combined distraction osteogenesis, bimaxillary anterior segmental surgery with extraction of the 4 first premolars, and genioplasty. For achieving ideal and stable occlusal relationships, comprehensive orthodontic treatment was required before and after the operation. Moreover, the 4 developing third molars were extracted before treatment so as not to interfere with the orthognathic surgery.

Treatment progress

Initially, the patient was referred to specialists for treatment of a decayed tooth and extraction of all third molars. After that, 0.022 × 0.028-in preadjusted edgewise appliances were placed in both arches. With sequential nickel-titanium archwires, presurgical dental alignment and leveling were achieved in 5 months ( Fig 4 ), and 0.018 × 0.025-in stainless steel archwires were placed in the maxillary and mandibular dental arches before surgery.

Afterward, distraction osteogenesis was performed to correct the facial asymmetry. Via a submandibular incision and subperiosteal dissection, a lateral corticotomy was performed at the junction of the mandibular ramus and body. The distraction vector was placed at an angle of 60° with respect to the maxillary occlusal plane. After 7 days of latency, the distractor was activated at a rate of 1 mm per day until the deviation of the mandibular midline had been overcorrected by several millimeters. As shown in Figures 5 and 6 , the total increment in the length of the right mandibular ramus and body was approximately 30 mm, thereby leading to a transverse rotation of the mandible toward the left. As the distraction progressed, a posterior open bite developed on the right side, which was addressed via vertical intermaxillary elastics during the consolidation phase of the distraction osteogenesis.