Self-injurious behaviors (SIB) in patients who have developmental disabilities is a complex disorder, and its underlying etiologies are poorly understood. SIB is a significant factor in hospitalizations, decisions to use psychotropic medications, and institutional placement for people who have developmental disabilities. Because this group often manifests oral SIB, the dentist may be the first professional called upon to evaluate a patient. Dental therapy focuses on symptomatic treatment to minimize tissue damage caused by SIB, but addressing the underlying impetus for the behavior is essential for successful treatment. Determining definitive therapeutic interventions is difficult because of the mixed bio behavioral etiologies for SIB. This complication necessitates a team approach that includes medical and behavioral specialists.

Behaviors that result in self-induced wounds stem from a wide range of etiologies including those of an organic nature, those that seem to serve a function, or those that are habitual. Although some self-injurious behaviors (SIB) may be unintentional, when the term is used in the medical and psychiatric literature, it usually refers to intentional acts that result in organ or tissue damage.

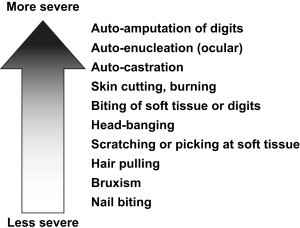

SIB encompasses a wide range of behaviors, some resulting in relatively minor tissue damage, others with very severe consequences ( Fig. 1 ). The medical sequelae of these behaviors can include soft tissue infection, loss of vision, injury to the dentition, bone fracture, as well as scarring and disfigurement. Additionally, side effects of psychotropic medications that are used to manage SIB can have long-term, unintended health consequences. SIB may also interfere indirectly with an individual’s social and educational opportunities.

Diverse populations have been known to exhibit SIB. These include individuals with psychiatric diagnoses such as bipolar disorder and depression, those with conditions that result in indifference to pain, such as familial dysautonomia, and others with a variety of developmental disabilities.

There is some variation in the behaviors engaged in by these different groups. Individuals with psychiatric disorders tend to engage more in non-oral forms of SIB, such as auto-amputation, cutting and burning of skin, or picking and scratching of soft tissue. SIB in this group also tends to be sporadic, rather than a chronic behavior. Oral SIB is seen more frequently in patients with intellectual disabilities, autism, and specific genetic disorders, most notably, Lesch-Nyhan syndrome. Although SIB in this group may be sporadic, in response to specific stimuli, the pattern more often tends to be chronic and/or stereotypic. Patients with disorders of decreased pain sensation may experience oral soft tissue self-inflicted wounds, but this is often not intentional in nature. This type of injury is related to an impaired ability to perceive and/or react to painful stimuli. Comatose or decerebrate patients may also experience severe oral soft tissue mutilation, but this, too, is unintentional and can be attributed to neuropathologic chewing that is associated with injury to the cerebral cortex and pyramidal system.

The focus of this article is oral SIB as manifested by individuals with developmental disabilities. Prevalence estimates of SIB in this group have ranged from 3.5% to 40%. In 1989, the National Institutes of Health estimated that approximately 25,000 people with developmental disabilities in the United States exhibit some type of SIB. In addition to the physical and psychologic hardships brought on by SIB, the behavior brings with it financial burdens. It is a significant factor in hospitalizations, decisions to use psychotropic medications, and institutional placement for people with developmental disabilities.

Risk factors for self-injurious behavior

The literature is replete with reports on SIB in patients with normal intellect and psychiatric disorders such as bipolar disorder, obsessive compulsive disorder, schizophrenia, borderline personality disorder, severe depression, eating disorders, and self-mutilation disorders. For the psychiatric population with SIB, the behavior is often described as a “relief” from psychic pain or tension. Yates proposed a psychopathology framework for SIB that is a result of childhood trauma such as sexual abuse. The psychopathology of SIB in patients with psychiatric diagnosis (but normal range of intelligence) most likely serves a different function than for individuals with intellectual disability (ID).

An increased incidence of SIB is noted in individuals with severe-to- profound intellectual disability and those with additional sensory impairments. Blindness in particular has been associated with increased risk of SIB. It is postulated that eye poking serves a self-stimulatory function in those with visual impairment. Presence of stereotypies (purposeless repetitive movements), movement disorders, and sleep disturbances are associated with the occurrence of SIB in patients with ID. As mentioned previously, individuals with a diagnosis of autism are also at increased risk for SIB. In McClintock and colleagues’ meta-analysis of studies of SIB in ID populations over the last 30 years, the top risk factors for SIB are listed as severe or profound ID, diagnosis of autism, and deficits in receptive or expressive communication. SIB has also been reported in patients with altered states of consciousness due to brain injury or infection. The lip or cheek may act as a bolus that initiates the chewing cycle in a patient without cerebral control of the masticatory muscles.

There have been several case reports of patients with cerebral palsy (CP) exhibiting SIB as a result of involuntary movement. Patients with seizure disorders, as well as Chiari type II malformation have also been reported to exhibit SIB.

Genetic syndromes associated with self-injurious behavior

Genetic disorders associated with SIB include: Lesch-Nyhan syndrome, Tourettesyndrome, Cornelia de Lange syndrome, familial dysautonomia, Fragile X, Leigh disease, Hallervorden-Spatz disease, Prader-Willi syndrome, Rett syndrome, and Richner-Hanhart syndrome. Several of the more commonly reported syndromes are detailed below.

Lesch-Nyhan syndrome (LNS) is an X-linked disorder of purine metabolism (specifically the lack of hypoxanthine-guanine phosphoribosyltransferase) that is perhaps the most notable genetic condition associated with SIB. Patients present with ID, choreoathetosis, hyperuricemia, uricosuria, and SIB. Biting of the lips, tongue, fingers, and hands is the predominant form of SIB in LNS patients and thus these patients are often referred to the dentist for treatment. The dental literature contains numerous reports of patients with LNS who have undergone a range of treatments with varying degrees of success.

Tourette syndrome (TS) is characterized by tics, both motor and vocal, as well as compulsions and attention deficits. The method of inheritance is unclear; however, familial history is implicated in nearly 50% of cases. Up to 60% of patients with TS exhibit SIB. Behavior such as lip and hand biting, head banging, and skin picking have been reported. Mathews and colleagues have correlated SIB with impulsivity, compulsivity, and affect disregulation, suggesting that in mild cases, SIB in TS may be closer to the SIB symptoms in psychiatric patients rather than patients with ID and other genetic syndromes.

Familial dysautonomia (also known as Riley-Day syndrome or hereditary sensory and autonomic neuropathy type III) is an autosomal recessive disorder. It is most often seen in patients of Ashkenazi Jewish descent. Patients have a progressive loss of small myelinated fibers and neurons in the autonomic and sensory ganglion. This inability to feel pain (eg, loss of pain as a protective mechanism) can result in accidental tissue damage such as biting, burns, and lacerations. Interestingly, these patients lack fungiform papillae and this unique finding can be diagnostically significant.

Individuals with Cornelia de Lange (CDL) syndrome have a characteristic appearance consisting of microbrachycephaly, micrognathia, low hairline, coarse hair, synophrys, and long eyelashes. Intellectual disability and foreshortened hands and feet are also features of this syndrome. Hyman and Oliver reported SIB in 62% of patients studied with CDL. Another report of two patients with CDL documented finger sucking, biting of digits and lips, and skin picking. It can be theorized that because these patients have many of the risk factors for SIB, including ID, “autistic tendencies,” lack of communication skills, and physical impairments, it is logical that there would be reports of SIB in this population.

Genetic syndromes associated with self-injurious behavior

Genetic disorders associated with SIB include: Lesch-Nyhan syndrome, Tourettesyndrome, Cornelia de Lange syndrome, familial dysautonomia, Fragile X, Leigh disease, Hallervorden-Spatz disease, Prader-Willi syndrome, Rett syndrome, and Richner-Hanhart syndrome. Several of the more commonly reported syndromes are detailed below.

Lesch-Nyhan syndrome (LNS) is an X-linked disorder of purine metabolism (specifically the lack of hypoxanthine-guanine phosphoribosyltransferase) that is perhaps the most notable genetic condition associated with SIB. Patients present with ID, choreoathetosis, hyperuricemia, uricosuria, and SIB. Biting of the lips, tongue, fingers, and hands is the predominant form of SIB in LNS patients and thus these patients are often referred to the dentist for treatment. The dental literature contains numerous reports of patients with LNS who have undergone a range of treatments with varying degrees of success.

Tourette syndrome (TS) is characterized by tics, both motor and vocal, as well as compulsions and attention deficits. The method of inheritance is unclear; however, familial history is implicated in nearly 50% of cases. Up to 60% of patients with TS exhibit SIB. Behavior such as lip and hand biting, head banging, and skin picking have been reported. Mathews and colleagues have correlated SIB with impulsivity, compulsivity, and affect disregulation, suggesting that in mild cases, SIB in TS may be closer to the SIB symptoms in psychiatric patients rather than patients with ID and other genetic syndromes.

Familial dysautonomia (also known as Riley-Day syndrome or hereditary sensory and autonomic neuropathy type III) is an autosomal recessive disorder. It is most often seen in patients of Ashkenazi Jewish descent. Patients have a progressive loss of small myelinated fibers and neurons in the autonomic and sensory ganglion. This inability to feel pain (eg, loss of pain as a protective mechanism) can result in accidental tissue damage such as biting, burns, and lacerations. Interestingly, these patients lack fungiform papillae and this unique finding can be diagnostically significant.

Individuals with Cornelia de Lange (CDL) syndrome have a characteristic appearance consisting of microbrachycephaly, micrognathia, low hairline, coarse hair, synophrys, and long eyelashes. Intellectual disability and foreshortened hands and feet are also features of this syndrome. Hyman and Oliver reported SIB in 62% of patients studied with CDL. Another report of two patients with CDL documented finger sucking, biting of digits and lips, and skin picking. It can be theorized that because these patients have many of the risk factors for SIB, including ID, “autistic tendencies,” lack of communication skills, and physical impairments, it is logical that there would be reports of SIB in this population.

Etiologies

Underlying etiologies for SIB are poorly understood. As research in this area progresses, it is quite possible that multiple neuropathologic mechanisms will be uncovered, all with the final outcome of self-injurious behavior.

Physicians and psychologists have been shown to differ in their approaches to research in the area of SIB etiologies. Many physicians, who tend to be biologically oriented, have theorized that SIB has a primary biologic basis. This theory implicates organic processes such as abnormalities in neurotransmitter pathways, hormone fluctuations; or SIB as a response to underlying pain (primarily in patients who have deficient communication skills). In support of this theory, painful stimulation has been shown to increase the release of endorphins, resulting in a pleasurable response. The fact that certain genetic syndromes, especially Lesch-Nyhan and Cornelia de Lange, have SIB as a prominent feature would also appear to support this biologic basis. In fact, imaging studies of patients with Lesch-Nyhan have demonstrated elevated numbers of dopamine receptors, accompanied by reductions in dopamine transporters and overall dopamine levels. Other papers have reported increased incidence of SIB associated with menstrual cycles. A study of 25 individuals who had been admitted to an in-patient unit for treatment of SIB showed that 28% had undiagnosed underlying medical problems that could be a source of discomfort. Conditions such as constipation, otitis media, gastroesophageal reflux, abscessed teeth, and pneumonia have been associated with periods of SIB in individuals with ID.

Psychologists, on the other hand, have investigated SIB as an operant phenomenon. This theory posits that SIB is a learned behavior, that it serves a specific function in the patient’s life, and that it can be modified by environmental changes and behavioral therapy. Behaviorists hypothesize that individuals may be motivated to use SIB in various situations:

- •

as an attention-getting device (positive reinforcement of behavior)

- •

as a means of obtaining materials or activities that may otherwise be inaccessible (positive reinforcement of behavior)

- •

as a way of avoiding stressful situations or undesirable tasks (negative reinforcement)

These situations are especially relevant to individuals who have limited cognitive abilities and/or compromised communication skills. The SIB acts, effectively, as a means of communication.

Patients with intellectual disability accompanied by severe sensory deficits, especially visual and auditory, receive little stimulation from the surrounding environment. It is possible that the increased incidence of SIB in this population may be interpreted as serving a pleasurable, self-stimulatory function.

Functional analysis

The ability to make appropriate treatment decisions is dependent on accurate diagnosis. Unfortunately, it can be very difficult to pinpoint underlying causes for SIB. Functional analysis provides a methodical system that can help interpret what environmental conditions are responsible for triggering episodes of SIB. It can also be useful in distinguishing when an underlying medical condition, rather than environment, might be responsible for a person’s SIB.

Briefly, during a functional analysis, a patient will be placed in several experimental conditions. During each of these controlled sessions, various behavioral reinforcers are presented to the patient. Observations will determine, which, of any, of these reinforcers results in SIB. An example of this is the “escape” condition, in which the patient is requested to perform a task (ie, putting away toys, helping to clean a kitchen). If the request provokes SIB, a break is provided, and the patient is ignored. The observer will then determine if escape from the demand results in a lessening of the SIB. Increased incidence of SIB in this type of situation would indicated that the patient has “learned” that SIB is a technique for avoiding undesirable demands. Other contingencies that might be tested are social interaction (attempting to attract attention via SIB), and using SIB in an attempt to obtain items such as toys or food.

The control situation is observation of the patient alone, without any demands and without the ability to interact with another person. In other words, the patient receives no reinforcement, either positive or negative, in response to an incident of SIB. Persistence of SIB during this “alone” contingency is an indication that the behavior may have a biologic, or internal, reinforcer rather than an environmental, or external, one. This type of automatic SIB warrants investigation into underlying medical conditions as a cause for the behavior.

Frequently, the results of a functional analysis may not be clear-cut. Many individuals have mixed bio-behavioral etiologies for SIB, a complication that makes definitive therapeutic interventions difficult.

Management of self-injurious behavior

A review of the medical, psychiatric, and dental literature reveals several common themes regarding the treatment of SIB. It is clear that the underlying mechanism of the patient’s behavior must be understood (ie, what purpose does the SIB serve?). Because many such patients lack communication skills, it may be a “cry for help.” A thorough medical assessment is needed to rule out undiagnosed medical reasons for SIB such as otitis media, infection, and pneumonia. Should no physical cause be found, and the patient is determined to be in good physical health, then a psychiatric evaluation may be advisable to determine the existence of comorbid psychiatric conditions that may respond to pharmacotherapy.

The dental literature consists largely of individual case reports. Most of these focus on appliance therapy to manage SIB. Management with soft resin bite guards (ie, sports guards), acrylic mouth guards, lip bumpers or plumpers, oral screens or tongue shields, appliances attached to head gear or helmets, acrylic splints attached with brass ligatures, and acrylic appliances designed with blocks to maintain an open bite have all met with varying degrees of success.

Patients with LNS are particularly refractory to appliance therapy and several authors have ultimately opted for extraction as treatment Cusamano, in his review of LNS, points out that appliance therapy should be tried first and extraction should be a last resort. However, in a study by Anderson and Ernst, 60% of parents of children with LNS would prefer extraction over appliance therapy. A report of crown amputation and pulpotomies in an LNS patient offers a treatment alternative to extraction.

Patients with familial dysautonomia may require extraction of primary teeth to prevent SIB to the lips and cheeks. These patients can later be taught not to bite.

Alternative therapies such as botulinum toxin injections in the orofacial musculature and orthognathic surgery to create an open bite have been reported to be successful in extinguishing SIB.

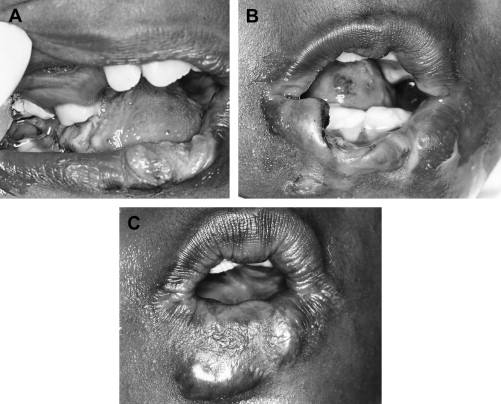

Dental therapy has focused on symptomatic treatment rather than attempts to treat the underlying mechanism of SIB. It should be noted, however, that although this type of therapy may extinguish oral SIB, the failure to address underlying reasons for the behavior may result in the emergence of other forms of SIB ( Fig. 2 A–C ).

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses