Since its discovery in the 1980s, HIV has infected every continent on the globe by crossing socioeconomic, racial, ethnic, and gender barriers, and it continues to contribute to human morbidity and mortality. Advances in medicine and technology have led to new combination medications for HIV-positive patients, early HIV testing methodologies, and potential for an HIV vaccine, and they have given researchers and clinicians a larger armamentarium with which to treat and prevent the disease. Even with these vast improvements in HIV prevention, detection, and treatment, scientists have been unsuccessful in developing its vaccine. Therefore, the search for a cure for HIV remains the marathon of the millennium.

Since its discovery in the 1980s, HIV has infected every continent on the globe by crossing socioeconomic, racial, ethnic, and gender barriers, and continues to contribute to human morbidity and mortality. Advances in medicine and technology have lead to new combination medications for HIV-positive patients, early HIV testing methodologies, and potential for an HIV vaccine, and they have given researchers and clinicians a larger armamentarium with which to treat and prevent the disease. Even with these vast improvements in HIV prevention, detection, and treatment, scientists have been unsuccessful in developing its vaccine. Therefore, the search for a cure for HIV remains the marathon of the millennium. Dr. Berkley, President and CEO of the International AIDS Vaccine Initiative, states, “With patience and a belief in science, we expect to succeed. And when we have –and AIDS has gone the way of polio and smallpox—people will look back with gratitude on the realists who knew that the only impossible thing was giving up.”

Thirty-three million people are currently infected with HIV worldwide (1.1 million in the United States), and as of 2007, 26 million people worldwide have died of AIDS (566,000 in the United States, as of 2006). While our military forces fight the Global War on Terror, scientists and HIV activists strive to combat the global HIV/AIDS pandemic. The demographics of the disease continue to change within and among country and world populations, with new United States cases growing fastest among minority women. Because of advances in medicine, HIV-positive patients are living longer with a chronic disease, rather than succumbing to death from acute complications of AIDS. Additionally, advances in science and technology are resulting in the development of new diagnostic modalities, as well as medicines that target specific steps in the HIV lifecycle. With numbers of people living with HIV/AIDS continuing to increase, the search for eradication of this disease continues. The National Institute of Health (NIH) is currently conducting trials with multiple medications in hopes of developing a vaccine to prevent this continued global pandemic. This article reviews the current definitions and classifications of HIV and AIDS, the historical timeline from discovery of HIV until present, HIV pathogenesis, transmission of HIV and infection control issues in a clinical setting, antiretroviral therapy and potential drug interactions, rapid HIV testing, research efforts toward a vaccine, and discussion of the Ryan White Care Act.

History of HIV and AIDS

The history of HIV can be traced back to sub-Saharan Africa, as far back as the 1930s. In 1959, scientists isolated a virus in a human male from the Democratic Republic of Congo. They believe this virus, which was genetically similar to HIV-1 and was called SIVcpz (Chimpanzee Simian Immunodeficiency Virus), migrated from the common chimpanzee to human beings when hunters were exposed to infected ape blood. Using genetic sequencing, scientists later isolated HIV-1, group M, subtype B in a group of the earliest Haitian AIDS patients. According to their findings, this HIV clade originated in central Africa in the 1930s and arrived in Haiti in 1966, when a Haitian professional returned from working in the newly independent Congo. After circulating in Haiti, the virus diversified before migrating to the United States around 1969. It continued to diversify and cryptically circulated among United States homosexual populations until 1981, when AIDS was recognized.

The 1980s and 1990s serve as the most significant historical period for HIV thus far, as this period marked the isolation and discovery of the virus that causes AIDS, the creation of guidelines to define levels of HIV infection and AIDS, and the beginning of the HIV epidemic. In 1981, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) reported five homosexual males in California with biopsy-confirmed Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia, as well as 26 cases of Kaposi’s sarcoma throughout the United States. By 1982, the CDC was able to link these opportunistic infections to a new blood-borne disease, which they called “Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome” or AIDS. Multiple scientists from around the world began searching for an etiology for this disease, including Dr. Robert Gallo of the National Cancer Institute, Dr. Luc Montagnier from the Pasteur Institute in France, and Dr. Jay Levy from the University of California at San Francisco. Each of these scientists identified a retrovirus as the cause of AIDS. However, in 1983, Dr. Luc Montagnier discovered the actual virus we know today as HIV. Because all three scientists had such a profound impact on the discovery of the virus, the President of the United States and the Prime Minister of France made a joint agreement in 1987 to share credit for HIV’s discovery. Discovery of the virus stimulated the scientific and medical communities to not only search for a cure from HIV, but also create infection-determining methodologies and epidemiologic-reporting mechanisms.

The 1990s were equally significant as the 1980s for the history of HIV. During this time period, the public became keenly aware of the virus through the efforts of Ryan White and Kimberley Bergalis. In 1990, Ryan White, a young hemophiliac patient who acquired HIV from a blood transfusion, died. However, before he died, he became an HIV/AIDS activist, gaining support from such famous personalities as Elton John and Michael Jackson, and even testifying on HIV/AIDS awareness before Congress. Then, in 1991, Kimberly Bergalis, a dental patient in Florida, made news headlines after acquiring the virus from her dentist. She, too, brought about public awareness of the disease, requesting Congress to mandate testing for all health care personnel. With awareness came increased knowledge about the sequelae of HIV infection, opportunistic infections. Therefore, by 1993, the CDC revised the definition of AIDS to include these opportunistic infections.

Today, HIV is the leading cause of death worldwide among people ages 15 to 59. Approximately 33 million people are living with HIV/AIDS, the majority of whom reside in developing countries. These countries not only lack the infrastructure to combat HIV, but they still have cultural, financial, religious, and discriminatory barriers that prevent them from caring for their infected and affected populations. The resultant profound effects on these populations include a reduction in their economic growth and development, a stunting of their educational systems, and a decrease in their food supply. Therefore, the HIV pandemic has been described as multiple epidemics.

The onset, prevalence, and transmission of the disease remain dynamic and vary among and within countries and world populations. For example, sub-Saharan Africa remains the region with the highest prevalence of adult and childhood HIV cases. The majority of these cases are transmitted through heterosexual contact or from mother to child. Women comprise over 50% of these reported infections. Alternatively, the HIV epidemic was first recognized in the United States as a disease with its transmission most associated with homosexual populations. However, current data suggests the primary mode of HIV transmission in the United States has changed from homosexual to heterosexual contact, with the fastest growing numbers of AIDS cases among young African American females (49%). Finally, in areas of Europe and Asia, HIV disproportionately affects intravenous drug abusers, men having sex with men, and sex workers. Because of their population growth and proximity, epidemiologists predict that countries in these regions will see the next HIV epidemic.

Definition and classification

HIV is derived from the Retroviridae family of viruses and is a member of the genus, Lentivirus. Two species of this retrovirus infect human beings: HIV-1 and HIV-2. These viruses are the etiology of AIDS. HIV-1 originated from the common chimpanzee, is more virulent than HIV-2, and is responsible for the majority of global HIV infections, including the majority of infections in the United States. HIV-2 originated from the Sooty Mangabay, is less virulent, and is mostly confined to West Africa. HIV-1 can be subdivided into three main groups: M (90% of HIV-1 infections), N (a rare group discovered in Cameroon in 1998), and O (a group restricted to West-central Africa). Group M may be further divided into nine subtypes, called clades: A, B, C, D, F, G, H, J, and K. HIV-1, group M, subtype B is the most widespread HIV variant.

Individuals infected with the HIV virus are called “HIV-positive” and are classified according to the CDC’s 1993 Revised Classification System for HIV Infection and Expanded Surveillance Case Definition for AIDS Among Adolescents and Adults or its 1994 Revised Classification System for Human Immunodeficiency Virus Infection in Children Less Than 13 Years of Age. The classification system for adolescents and adults categorizes individuals based on their clinical conditions associated with HIV infection (Categories A, B, C) and their CD4 + T lymphocyte counts per microliter of blood (Categories 1, 2, 3). It is based on four criteria: ( i ) repeatedly reactive screening tests for HIV antibody, with the specific antibody identified by the use of supplemental tests (eg, Western blot, immunofluorescence assay); ( ii ) direct identification of the virus in host tissues by virus isolation; ( iii ) HIV antigen detection; or ( iv ) a positive result on any other highly-specific, licensed test for HIV. Category A patients have asymptomatic HIV infection, persistent generalized lymphadenopathy, or acute (primary) HIV infection with accompanying illness or history of acute HIV infection. Category B patients display clinical conditions that are attributed to HIV infection, indicative of a defect in cell-mediated immunity or are considered by physicians to have a clinical course that is complicated by HIV infection. Common examples of conditions in clinical Category B include, but are not limited to: oropharyngeal candidiasis (thrush), fever (38.5° C), diarrhea lasting greater than 1 month, oral hairy leukoplakia, or Herpes zoster (shingles) involving at least two distinct episodes or more than one dermatome. Patients that fall into Category C have one of 26 AIDS indicator conditions. Examples of such conditions include, but are not limited to: esophageal candidiasis, extrapulmonary cryptococcosis, HIV-related encephalopathy, Human Herpes Virus I (HHV) greater than 1 month in duration, Kaposi’s sarcoma, Mycobacterium tuberculosis , or Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia. The three CD4+ T-lymphocyte categories are defined as follows: Category 1 patients have T cell counts greater than or equal to 500 cells/uL, Category 2 patients have T cell counts between 200 and 499 cells/uL, and Category 3 patients have T cell counts less than 200 cells/uL. Patients in clinical Category 3 are also referred to as patients with the diagnosis of AIDS. Children less than 13 years of age infected with HIV are classified into mutually exclusive categories according to three parameters: ( i ) infection status, ( ii ) clinical status, and ( iii ) immunologic status. This article does not discuss the details of the HIV classification system for children under 13 years of age.

Definition and classification

HIV is derived from the Retroviridae family of viruses and is a member of the genus, Lentivirus. Two species of this retrovirus infect human beings: HIV-1 and HIV-2. These viruses are the etiology of AIDS. HIV-1 originated from the common chimpanzee, is more virulent than HIV-2, and is responsible for the majority of global HIV infections, including the majority of infections in the United States. HIV-2 originated from the Sooty Mangabay, is less virulent, and is mostly confined to West Africa. HIV-1 can be subdivided into three main groups: M (90% of HIV-1 infections), N (a rare group discovered in Cameroon in 1998), and O (a group restricted to West-central Africa). Group M may be further divided into nine subtypes, called clades: A, B, C, D, F, G, H, J, and K. HIV-1, group M, subtype B is the most widespread HIV variant.

Individuals infected with the HIV virus are called “HIV-positive” and are classified according to the CDC’s 1993 Revised Classification System for HIV Infection and Expanded Surveillance Case Definition for AIDS Among Adolescents and Adults or its 1994 Revised Classification System for Human Immunodeficiency Virus Infection in Children Less Than 13 Years of Age. The classification system for adolescents and adults categorizes individuals based on their clinical conditions associated with HIV infection (Categories A, B, C) and their CD4 + T lymphocyte counts per microliter of blood (Categories 1, 2, 3). It is based on four criteria: ( i ) repeatedly reactive screening tests for HIV antibody, with the specific antibody identified by the use of supplemental tests (eg, Western blot, immunofluorescence assay); ( ii ) direct identification of the virus in host tissues by virus isolation; ( iii ) HIV antigen detection; or ( iv ) a positive result on any other highly-specific, licensed test for HIV. Category A patients have asymptomatic HIV infection, persistent generalized lymphadenopathy, or acute (primary) HIV infection with accompanying illness or history of acute HIV infection. Category B patients display clinical conditions that are attributed to HIV infection, indicative of a defect in cell-mediated immunity or are considered by physicians to have a clinical course that is complicated by HIV infection. Common examples of conditions in clinical Category B include, but are not limited to: oropharyngeal candidiasis (thrush), fever (38.5° C), diarrhea lasting greater than 1 month, oral hairy leukoplakia, or Herpes zoster (shingles) involving at least two distinct episodes or more than one dermatome. Patients that fall into Category C have one of 26 AIDS indicator conditions. Examples of such conditions include, but are not limited to: esophageal candidiasis, extrapulmonary cryptococcosis, HIV-related encephalopathy, Human Herpes Virus I (HHV) greater than 1 month in duration, Kaposi’s sarcoma, Mycobacterium tuberculosis , or Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia. The three CD4+ T-lymphocyte categories are defined as follows: Category 1 patients have T cell counts greater than or equal to 500 cells/uL, Category 2 patients have T cell counts between 200 and 499 cells/uL, and Category 3 patients have T cell counts less than 200 cells/uL. Patients in clinical Category 3 are also referred to as patients with the diagnosis of AIDS. Children less than 13 years of age infected with HIV are classified into mutually exclusive categories according to three parameters: ( i ) infection status, ( ii ) clinical status, and ( iii ) immunologic status. This article does not discuss the details of the HIV classification system for children under 13 years of age.

Pathogenesis of HIV

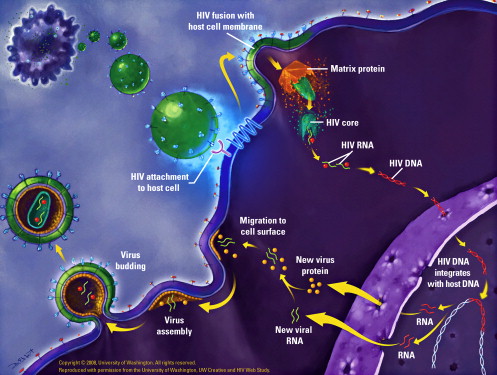

HIV is a 120-nm retrovirus consisting of two copies of positive single-stranded RNA enclosed by a capsid of viral proteins and surrounded by a double-layered phospholipid envelope. Each viral particle consists of 72 copies of a complex protein made up of glycoproteins 120 and 41 that traverse this phospholipid envelope and enable the virus to attach and fuse to target cells. The virus sustains itself through release of viral RNA and multiple viral enzymes into host CD4+ T cells, macrophages, and microglial cells. Its life cycle consists of six steps: binding/fusion, reverse transcription, integration, transcription, translation, and viral assembly and maturation ( Fig. 1 ). During binding, glycoprotein 120 (gp 120) adheres to the CD4+ T cell, macrophage, or microglial cell, causing a conformational change in the structure of gp120. While binding is crucial for viral entry, interferes with intracellular signal transduction, and promotes CD4+ apoptosis, this conformational change allows interaction of gp 120 with its coreceptor, CCR5 or CXCR4, enabling fusion. Membrane fusion is dependent on coreceptor binding and is facilitated by glycoprotein 41 (gp41). Once fusion occurs, the two single strands of viral RNA within the viral capsid are released into the host cell cytoplasm, leaving the viral envelope behind. The virus then releases an enzyme, reverse transcriptase, which converts the two strands of viral RNA into double stranded DNA. The viral DNA is transported to the host cell nucleus, where it is incorporated into the host DNA through the action of the viral enzyme, integrase. Once the viral DNA is integrated, the virus is called provirus. This provirus may remain dormant for years; however, once the cell is activated, the two strands of viral DNA separate and are converted into messenger RNA (transcribed) by the host enzymes. The messenger RNA is then carried outside the nucleus to the mitochondria and processed. As each portion of the messenger RNA is read by the mitochondria, a complementary set of proteins is made (translation). The proteins are cut by a viral enzyme, protease, and then used to create either new viral particles or viral enzymes. These new proteins and enzymes are then assembled and placed inside buds, which extrude from the cell. The buds of new immature viral proteins and enzymes break away from the infected host cell. Shortly after leaving the host cell, viral proteinases become active, cleaving the viral proteins to generate a mature form of HIV. Once mature, the virus is infective.

HIV transmission and occupational risk

Knowledge of HIV modes of transmission and its pathogenesis are essential for the prevention of HIV infection. HIV is mainly found in blood, semen, vaginal fluids, and breast milk, and is transmitted through direct contact with these fluids via sexual contact, intravenous drug use, mother-to-child transfer, or occupational exposure. The virus has also been found in small amounts in the saliva and tears of AIDS patients. Oral health care personnel, in particular, are at an increased risk for occupational exposure from a percutaneous injury because of their frequent use of needles and exposure to blood and saliva. However, no cases of HIV transmission through saliva, sweat, or tears from AIDS patients have been recorded.

Factors that influence occupational risk include frequency of infection among patients, type of virus, and type and frequency of blood contact. Likewise, risk factors that affect transmission after a percutaneous injury include depth of the injury, amount of blood on the instrument, proximity of instrument to a vessel, and the disease status of the patient. Finally, virulence of the infectious organism must also be considered. Health care personnel are more likely to acquire an infection from a Hepatitis virus, such as B or C, than HIV. The CDC reports that the risk of acquiring Hepatitis C from a needle stick injury is 1.8%, while the risk of acquiring HIV from the same injury is only 0.3%. Occupational exposure to HIV through a percutaneous injury is considered a medical urgency and should be handled in a timely manner to ensure appropriate postexposure management. The CDC has developed postexposure prophylactic guidelines for health care personnel exposed to HIV-contaminated blood. These guidelines include taking a 4-week regimen of two drugs (zidovudine [ZDV] and lamivudine [3TC]; lamivudine [3TC] and stavudine [d4T]; or didanosine [ddl] and d4T) and serve to minimize the risk of seroconversion after percutaneous injury. The best management of any medical urgency or emergency is prevention. Therefore, health care personnel should implement the elements of universal precautions such as hand-washing, use of personal protective equipment, care of patient equipment and environmental surfaces, and injury preventive measures when treating patients.

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses