Current research shows that women tend to receive less dental care than usual when they are pregnant. In 2012, the first national consensus statement on oral health care during pregnancy was issued, emphasizing both the importance and safety of routine dental care for pregnant women. This article reviews the current recommendations for perinatal oral health care and common oral manifestations during pregnancy. Periodontal disease and its association with preterm birth and low birth weight are also discussed, as is the role played by dental intervention in these adverse outcomes.

Key points

- •

A 2012 national experts’ consensus statement concludes that dental care is safe and effective throughout all trimesters of pregnancy, and should not be withheld because of pregnancy.

- •

Research to date shows that routine preventive, diagnostic, and restorative dental treatment—including periodontal therapy—during pregnancy does not increase adverse pregnancy outcomes.

- •

The pregnant patient should be educated on the importance of oral health care for herself and her child and on expert recommendations for bolstering home oral hygiene care during pregnancy.

- •

Oral manifestations may be associated with pregnancy, including gingivitis, pregnancy epulis, and others.

- •

Research to date supports the safety of undertaking periodontal treatment during the perinatal period, with no associated adverse pregnancy outcomes. Whether perinatal periodontal treatment can reduce the risks for preterm birth or low birth weight has not been demonstrated thus far in US multicentered randomized controlled trials.

Introduction

Pregnancy is a unique period during a woman’s life and is characterized by complex physiologic changes, which can adversely affect oral health. Because oral health is an integral part of overall health, oral problems encountered in the pregnant patient must be promptly and properly addressed. Several national health organizations have issued statements in recent years calling for improved oral health care during pregnancy.

Accumulated research shows that routine preventive, diagnostic, and restorative dental treatment—including periodontal therapy—during pregnancy does not increase adverse pregnancy outcomes. The first national consensus statement issued in 2012 concluded such dental care is both safe and effective throughout pregnancy. Nonetheless, many women currently do not seek or do not receive dental care during the perinatal period. Recent data suggest that about 50% of women do not have a dental visit during pregnancy, even when they perceive a dental need. In addition, women with both private dental insurance and Medicaid coverage receive less dental care when they are pregnant than when they are not. Factors for some women may include lack of insurance coverage or access, and it is possible that those with Medicaid coverage receive less dental care than those with other dental insurance plans. Research also suggests that misperceived barriers and inadequate knowledge about evidence-based perinatal dental care on the part of both patients and health care providers also play a role in underutilization.

This article provides a summary of the most current evidence-based perinatal oral health guidelines, a review of common oral health manifestations during pregnancy, and insights into the safety and effectiveness of periodontal treatment on maternal and fetal outcomes.

Introduction

Pregnancy is a unique period during a woman’s life and is characterized by complex physiologic changes, which can adversely affect oral health. Because oral health is an integral part of overall health, oral problems encountered in the pregnant patient must be promptly and properly addressed. Several national health organizations have issued statements in recent years calling for improved oral health care during pregnancy.

Accumulated research shows that routine preventive, diagnostic, and restorative dental treatment—including periodontal therapy—during pregnancy does not increase adverse pregnancy outcomes. The first national consensus statement issued in 2012 concluded such dental care is both safe and effective throughout pregnancy. Nonetheless, many women currently do not seek or do not receive dental care during the perinatal period. Recent data suggest that about 50% of women do not have a dental visit during pregnancy, even when they perceive a dental need. In addition, women with both private dental insurance and Medicaid coverage receive less dental care when they are pregnant than when they are not. Factors for some women may include lack of insurance coverage or access, and it is possible that those with Medicaid coverage receive less dental care than those with other dental insurance plans. Research also suggests that misperceived barriers and inadequate knowledge about evidence-based perinatal dental care on the part of both patients and health care providers also play a role in underutilization.

This article provides a summary of the most current evidence-based perinatal oral health guidelines, a review of common oral health manifestations during pregnancy, and insights into the safety and effectiveness of periodontal treatment on maternal and fetal outcomes.

Perinatal oral health guidelines

Over the last decade, several state organizations have issued evidence-based guidelines on perinatal oral health, including California, New York, South Carolina, and Washington. The American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry also issued guidelines, highlighting the important influence of maternal oral health care and knowledge on their children’s oral health. These guidelines and a review of the recent medical literature culminated in the first national guidelines issued in 2012: Oral Health Care During Pregnancy: A National Consensus Statement of an Expert Workgroup Meeting. This workgroup and meeting were sponsored by the Health Resources and Services Administration’s Maternal and Child Health Bureau in collaboration with the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists and the American Dental Association. Key concepts from the 2012 consensus statement are reviewed here.

When to Consult with Prenatal Care Health Professionals

In general, the national consensus states that dental care can be safely delivered during all trimesters of pregnancy. It is important, however, to consult with a patient’s prenatal care provider when considering any of the following :

- •

Comorbid conditions that could affect management of the patient’s oral problems, such as diabetes, hypertension, pulmonary or cardiac disease, and bleeding disorders

- •

The use of intravenous sedation or general anesthesia

- •

The use of nitrous oxide as an adjunct to local anesthetics

Safety of Dental Treatment During Pregnancy

Pregnant women deserve the same level of care as any other dental patient, and clinicians now have an evidence base that shows appropriate dental care as being both necessary and safe during the perinatal period. There have been three published US randomized clinical trials in which standard dental treatment was provided to pregnant women. Overall, these studies confirmed the safety of this treatment to the pregnant woman and the fetus. Among women who know they are pregnant, the risk of miscarriage before 20 weeks of pregnancy is between 15% and 20%, and most miscarriages are not preventable. By definition, the risk of teratogenicity (the ability to cause birth defects), whether from imaging procedures, medications, or other medical treatments, must take place prior to 12 weeks gestation. There is little evidence that the medications used in standard dental practice have a teratogenic effect. Necessary dental imaging studies with appropriate maternal body shielding have not been associated with adverse pregnancy outcomes.

The following sections review the evidence-based consensus on dental-related treatments.

Medications and anesthesia

There is considerable confusion among dental health care providers about medication safety during pregnancy. The national consensus panel released evidence-based guidelines related to pharmaceutical agents, including analgesics, antibiotics, anesthetics, and antimicrobials ( Table 1 ).

| Pharmaceutical Agent | Indications, Contraindications, and Special Considerations |

|---|---|

| Analgesics | |

| Acetaminophen | May be used during pregnancy |

| Acetaminophen with codeine, hydrocodone, or oxycodone | |

| Codeine | |

| Meperidine | |

| Morphine | |

| Aspirin | May be used in short duration during pregnancy; 48–72 h. Avoid in first and third trimesters |

| Ibuprofen | |

| Naproxen | |

| Antibiotics | |

| Amoxicillin | May be used during pregnancy |

| Cephalosporins | |

| Clindamycin | |

| Metronidazole | |

| Penicillin | |

| Ciprofloxacin | Avoid during pregnancy |

| Clarithromycin | |

| Levofloxacin | |

| Moxifloxacin | |

| Tetracycline | Never use during pregnancy |

| Anesthetics | Consult with a prenatal care health professional before using intravenous sedation or general anesthesia |

| Local anesthetics with epinephrine (eg, bupivacaine, lidocaine, mepivacaine) | May be used during pregnancy |

| Nitrous oxide (30%) | May be used during pregnancy when topical or local anesthetics are inadequate. Pregnant women require lower levels of nitrous oxide to achieve sedation; consult with prenatal care health professional |

| Over-the-counter antimicrobials | Use alcohol-free products during pregnancy |

| Cetylpyridinium chloride mouth rinse | May be used during pregnancy |

| Chlorhexidine mouth rinse | |

| Xylitol |

Few clinical drug trials have included pregnant women; therefore, successful long-term clinical use without known adverse effects is the best available evidence supporting the safety of a given drug.

Older, reliable anesthetics and medications that have a solid track record of low-incidence adverse effects should always be the first choice. Some examples include local anesthetics such as lidocaine 2% with 1:100,000 epinephrine and mepivacaine 3%; antibiotics such as penicillin, amoxicillin, and clindamycin; antifungals such as nystatin; and short-term use of analgesics such as acetaminophen with codeine. Providers should also be familiar with medications that are contraindicated in pregnancy, and all guidelines mentioned earlier include these agents.

A dental provider must always ask if the benefit to the mother and fetus of taking a medication, whether to control infection, pain, or other disease processes, is greater than the potential downside of not using the medication to manage or treat the underlying problem. It is judicious to contact the patient’s primary care provider or obstetrician/gynecologist if there are questions or concerns.

Radiographs

The 2012 consensus statement and other guidelines advise that radiographic imaging is not contraindicated during pregnancy. As for any patient, the standard of care is to take the minimum number of images required for a comprehensive examination, diagnosis, and treatment plan. As with all patients, a thyroid collar and abdominal apron should be used.

Sedation and anesthesia

The use of nitrous oxide should be limited to situations whereby topical and local anesthetics are inadequate and care is essential. As mentioned earlier, the patient’s prenatal care provider should always be consulted when considering the use of nitrous oxide, intravenous sedation, or general anesthesia.

Extractions, Restorations, Root Canals, and Other Dental Treatments

Data from the Obstetrics and Periodontal Therapy Trial showed that women who receive fillings or who undergo extractions or root canal treatment during the second trimester of pregnancy do not experience higher rates of adverse birth outcomes compared with women who do not undergo these dental treatments. Oral health professionals should recommend prompt treatment when needed, and collaborate with the patient to determine appropriate treatments and restorative materials because of the risks associated with untreated caries in pregnant women. For amalgam, there is no evidence of any harmful effects from both population-based studies and reviews, and there should be no additional risk if standard safe amalgam practices, including rubber-dam placement and use of high-volume suction, are used. For composite resins, the current evidence base shows that short-term exposure associated with placement does not pose any health risk. However, data are lacking on the effects of long-term exposure. With any material, best practices should be used to minimize risk, such as rubber-dam placement and immediate rinsing of cured surfaces to remove the unpolymerized layer.

With regard to periodontal disease, meta-analyses of clinical trials have shown that women who receive anesthesia and scaling and root planing (SRP) during the second trimester do not experience higher rates of adverse birth outcomes in comparison with women who do not undergo these treatments. Additional information about periodontal disease during pregnancy is included later in this article.

Advising and Educating Patients During Pregnancy

Educating women about oral health care

Pregnancy provides a unique opportunity to deliver oral health preventive information and services that benefit 2 individuals at the same time: the mother and her child. The basis for developing the appropriate preventive approach is risk assessment, which will identify the lifestyle and behavior changes a woman can make to lower her risk for dental disease. Many of these habits and decisions will also affect her child’s oral health.

Educating women about how their own oral health can affect their child’s is a powerful tool. A survey of pregnant Minnesota women with public and private insurance showed a preference for infant-specific educational information over education on topics that concerned both mother and infant. In addition, 68% of the women preferred receiving oral health information by mail, compared with 34.4% who favored face-to-face delivery. How information is presented in person is critical. Behavioral approaches that determine readiness for change are more appropriate than simply telling a patient what to do. When selecting health education materials for pregnant women, characteristics of the dental practice and the community it serves are important. Having materials that are appropriate to the literacy level, language, and culture of the patient is critical to reinforcing the verbal message.

Recommended oral hygiene during pregnancy

According to the National Consensus, pregnant women should be advised to continue with routine dental visits every 6 months and to schedule a dental appointment as soon as possible if oral health problems or concerns arise.

Pregnant women should also be advised to adhere to the following oral hygiene regimen at home :

- •

Brush teeth with fluoridated toothpaste twice daily, and clean between teeth daily with floss or an interdental cleaner.

- •

Rinse daily with an over-the-counter fluoridated, alcohol-free mouth rinse. After eating, chew xylitol-containing gum or use other products, such as mints, with xylitol to help reduce bacteria that can cause decay.

- •

After vomiting, rinse the mouth with 1 teaspoon of baking soda dissolved in a cup of water to stop acid from attacking teeth.

- •

Eat healthy foods and minimize sugar consumption.

In certain instances, chlorhexidine antimicrobial rinse (alcohol-free formulation) may be indicated for optimal gingival health.

Patient comfort during pregnancy

With very simple modifications, dental treatment can be comfortable for the patient throughout pregnancy. The following steps can help :

- •

Treatment at any time during the pregnancy, including the first trimester, can be safe and effective. However, the early second trimester (at 14–20 weeks) is traditionally considered more comfortable, because nausea and postural issues are often less of a problem.

- •

Instruct your scheduling person to query “What time of day do you feel best coming in for your appointment?”

- •

Position pregnant patients for comfort. Postural hypotensive syndrome is a clinical concern and occurs in 15% to 20% of term pregnant women when supine. To decrease the risk for hypotension, place a small pillow under the patient’s right hip and ensure her head is raised above her feet when reclining. If a patient feels dizzy or faint or reports chills, position her on her left side to relieve pressure and restore circulation. These symptoms are commonly caused by the weight of the pregnant uterus impinging on the inferior vena cava, thus impacting returning venous circulation.

- •

For women in later stages of pregnancy who must undergo longer procedures, be mindful of the need for frequent postural changes or a restroom break during treatment.

Common oral health manifestations during pregnancy

Pregnancy Gingivitis

Gingivitis is one of the most common findings during pregnancy, affecting 60% to 75% of all pregnant women. It is characterized by erythema of the gingiva, edema, hyperplasia, and increased bleeding ( Fig. 1 ). Gingival inflammatory changes are generally observed in the second or third month of pregnancy, persist or increase during the second trimester, and then decrease in the last month of pregnancy, eventually regressing after parturition. Histologically there are no differences between pregnancy gingivitis and other forms, but pregnancy gingivitis is characterized by an exaggerated response to local irritants, including bacterial plaque and calculus.

The underlying mechanism for this enhanced inflammatory response during pregnancy is elevated levels of progesterone and estrogen. The severity of the response is directly attributed to the levels of these hormones. Sex hormones also have an effect on the immune system. Sex hormones depress neutrophil chemotaxis and phagocytosis, as well as T-cell and antibody responses. Specific estrogen receptors have been identified in gingival tissues. Estrogen can increase cellular proliferation of gingival blood vessels, decreased gingival keratinization, and increased epithelial glycogen. These changes diminish the epithelial barrier function of the gingiva.

Progesterone increases vascular membrane permeability, edema of the gingival tissues, gingival bleeding, and increased gingival crevicular fluid flow. Progesterone also reduces the fibroblast proliferation rate and alters the rate and pattern of collagen production, reducing the ability of the gingiva to repair. The breakdown of folate, a requirement for maintaining healthy oral mucosa, is increased in the presence of higher levels of sex hormones. The subsequent relative folate deficiency increases the inflammatory destruction of the oral tissue by inhibiting its repair.

Sex hormones can also affect gingival health during pregnancy by allowing an increase in the anaerobic-to-aerobic subgingival plaque ratio, leading to a higher concentration of periodontopathic bacteria. A 55-fold increase in the level of Prevotella intermedia has been shown in pregnant women in comparison with nonpregnant women. P intermedia is able to substitute progesterone and estrogen for vitamin K, an essential growth factor.

To summarize, the increased levels of sex hormones found in pregnancy help depress the immune response, compromise the local defense mechanism necessary for good oral health, and reduce the natural protection of the gingival environment. These changes, combined with a microbial shift favoring an anaerobic flora dominated by P intermedia , are partly responsible for the exaggerated response to bacterial plaque in pregnancy. Generalized supragingival and/or subgingival periodontal therapies should be initiated in women with gingivitis to eliminate plaque buildup, as should intensive education on oral hygiene. Moreover, periodontal therapy can be effective in reducing signs of periodontal disease and the level of periodontal pathogens. Necessary periodontal care is important and should be undertaken, not postponed, during pregnancy.

Pregnancy Tumor (Epulis Gravidarum)

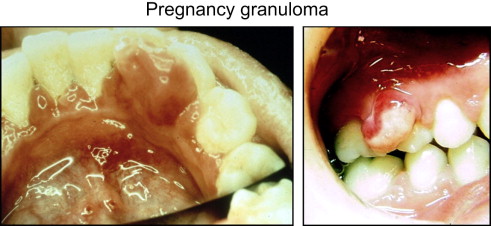

Pregnancy can also cause single tumor-like growths of gingival enlargement referred to as pregnancy tumor, epulis gravidarum, or pregnancy granuloma. The histologic appearance is a pyogenic granuloma observed in 0.2% to 9.6% of pregnant patients, usually during the second or third trimester. This lesion occurs most frequently in an area of inflammatory gingivitis or other areas of recurrent irritation, or as a result of trauma. It often grows rapidly, although it seldom becomes larger than 2 cm in diameter. Poor oral hygiene is variably present, and often there are deposits of plaque and calculus on the teeth adjacent to the lesion. The gingiva enlarges in a nodular fashion to give rise to the clinical mass ( Fig. 2 ). The fully developed pregnancy epulis is a sessile or pedunculated lesion that is usually painless. The color varies from purplish red to deep blue, depending on the vascularity of the lesion and the degree of venous stasis. The surface of the lesion may be ulcerated and covered by yellowish exudate, and gentle manipulation of the mass easily induces hemorrhage. Bone destruction is rarely observed around pregnancy granulomas.

SRP and intensive instruction on oral hygiene can, and should, be initiated before delivery to reduce plaque retention. In some situations the lesion may need to be excised during pregnancy, such as when it causes discomfort for the patient, disturbs the alignment of the teeth, or bleeds easily on mastication. The patient should be advised, however, that a pregnancy granuloma excised before term may recur. In general, the pregnancy granuloma will regress postpartum; however, surgical excision may be required for complete resolution.

Caries

The relationship between dental caries and pregnancy is not well defined. Changes in salivary composition in late pregnancy and during lactation may temporarily predispose to erosion as well as dental caries. There are no convincing data, however, to show that the incidence of dental caries increases during pregnancy or in the immediate postpartum period, although existing untreated caries will likely progress.

Pregnancy may cause food cravings, and if these are for cariogenic foods, the pregnant woman may increase her risk for caries at this time. All pregnant patients, therefore, should be advised to bolster their daily oral hygiene routine. For recommendations per the National Consensus, see the earlier section on recommended oral hygiene during pregnancy.

Xerostomia

Some pregnant women may experience temporary dryness of the mouth, for which hormonal alterations associated with pregnancy are a possible explanation. More frequent consumption of water and sugarless candy or gum may help alleviate this problem. More frequent fluoride exposure (toothpaste, mouth rinse) is also recommended for women who experience xerostomia, to help remineralize teeth and reduce the risk for caries.

Perimylolysis

Although nausea and vomiting are predominantly associated with early pregnancy, some women continue to experience this past the first trimester. Hyperemesis gravidarum, a severe form of nausea and vomiting that occurs in 0.3% to 2% of pregnant women, can lead to loss of surface enamel (perimylolysis) primarily through acid-induced erosion.

Pregnant patients should be queried about nausea and vomiting during their dental visits. Those who experience vomiting should be instructed to rinse the mouth immediately afterward with a teaspoon of baking soda dissolved in a cup of water, which can prevent acid from attacking teeth. These patients should also be advised to avoid brushing teeth immediately after vomiting. More frequent fluoride exposure to remineralize teeth is also recommended for women who experience repeated nausea and vomiting during pregnancy.

Tooth Mobility

Generalized tooth mobility in the pregnant patient is probably related to the degree of gingival diseases that disturb the attachment apparatus and to mineral changes in the lamina dura. Longitudinal studies demonstrate that as gingival inflammation increases, so do probing depths attributable to the swelling of the gingiva. Although most research concludes that generally no permanent loss of clinical attachment occurs during pregnancy, in some individuals the progression of periodontitis occurs, and may be permanent.

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses