INTRODUCTION

Head injury is a common problem, with about 500,000 cases reported yearly. While the majority of head injuries are classified as mild, 10% are moderate and 10% are severe. Patients with identified maxillofacial trauma are certainly more prone to neurologic injuries. In one retrospective study, 14.6% of blunt trauma patients (1068 patients) were diagnosed with facial fractures. Of the subgroup of blunt trauma patients with facial fractures, 79.4% (848 patients) suffered some form of brain injury by CT abnormality, clinical examination, or both.

A brief neurologic examination is crucial in the evaluation of trauma patients. Recognition of an abnormality on neurological examination can keep a treatable problem from becoming a catastrophic injury. The remainder of the chapter will outline the initial assessment/treatment/grading of injury severity, followed by a more focused neurologic evaluation of the trauma patient with significant attention to brain and spine injuries.

INITIAL ASSESSMENT

Unfortunately, the injury done to the brain at the time of the accident (initial insult) cannot be undone. However, through appropriate management, a secondary insult can be avoided and the patient’s outcome can be maximized. All trauma patients should be evaluated utilizing Advanced Trauma Life Support (ATLS) guidelines. Just as with any trauma patient, the ABCs (airway, breathing, circulation) still apply to the patient with a head or spinal cord injury. When managing the airway of a trauma patient, it is crucial to maintain C-spine immobilization, since there is a significant incidence of associated spinal injury with both head injury (5%) and in patients with an injury above the clavicle (15%). The trauma patient should have a hard collar applied and the patient should be placed on a spine board until the spines have been clinically and radiographically cleared.

Hypoxia is particularly devastating to head-injured patients. A recent study demonstrated a statistically significant increase in mortality of patients with prehospital hypoxia (odds ratio of 2.66, p < .05). This significant increase in mortality underscores the importance of adequate oxygenation in the head-injured patient. Patients with severe closed-head injuries should be intubated and mechanically ventilated. A Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) score of 8 or less should prompt the treating physician to endotracheally intubate the patient; if this is not possible, a surgical airway should be secured. Hyperventilation (PCO 2 below 25 mm Hg) is typically avoided except in situations of worsening GCS or pupillary dilatation. The preferable PCO 2 is 35-40 mm Hg for patients without elevated intracranial pressure and 30-35 mm Hg in the presence of elevated intracranial pressure.

Hypotension has also been shown to be very poorly tolerated by the head-injured patient. Hypotension (systolic blood pressure [SBP] <90 mm Hg) on admission has been shown to double the mortality in patients with severe closed head injury. Normal saline or Ringer’s lactate should be used for resuscitation with the goal of normovolemia. In the severely injured patient, two large-bore peripheral intravenous lines should be placed to administer the fluids. When necessary, pressors are given in addition to fluids to avoid hypotension (SBP <90). The use of hypotonic fluids and glucose-containing fluids should be avoided since these may worsen the outcome of the head-injured patient.

Securing an adequate airway and avoiding hypoxia and hypotension can significantly improve the head-injured trauma patient and represents the first step in avoiding secondary injuries.

HISTORY AND PHYSICAL EXAMINATION

After the initial resuscitation (ABCs), attention can be turned to a focused history and physical examination.

A brief history is obtained from the patient if possible. However, in the head-injured patient, it is often difficult or impossible to obtain a useful history. In this situation, the emergency personnel, nursing, and transferring physician notes can be used to help obtain pertinent information. With regard to head injuries, it is important to determine loss of consciousness, presence of seizure activity, and change or deterioration in mental status. With regard to spine injuries, history of numbness, weakness, and bowel or bladder dysfunction should be ascertained.

MENTAL STATUS

If the patient is conscious, ask the patient questions to check his or her orientation (month, day of the week, year, etc.). Assess the patient’s level of alertness. If the patient has difficulty remaining awake during questioning, that could be a sign of head injury. If the patient is unconscious or disoriented after trauma, a non-contrasted head CT scan should be obtained as soon as possible.

RESPIRATORY RATE/VITALS

Assess the patient’s respiratory pattern; injuries to the brain and brainstem can cause alterations in the normal rate and rhythm. The oxygen saturation and blood pressure should also be closely monitored. As mentioned previously, hypoxia and hypotension can worsen prognosis and should be aggressively treated. High blood pressure, bradycardia, and respiratory irregularity can be seen with intracranial hypertension (Cushing’s triad).

ASSOCIATED ABNORMALITIES

Special attention should also be given to the following regions when evaluating the patient with a possible neurologic injury.

SCALP

The scalp is a very vascular structure. A laceration can lead to significant blood loss. The entire scalp should be examined for lacerations. Logroll precautions should be used until the spine has been cleared (radiographically and/or clinically).

AURICULAR/PERIAURICULAR REGION

Battle’s sign is ecchymosis behind the ear and is typically associated with a basilar skull fracture. The external auditory canal should also be inspected for laceration and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) drainage; both can be seen with basilar skull fractures. The tympanic membrane should be inspected when possible. Blood seen behind the tympanic membrane is also an indication of a possible basilar skull fracture. The great majority of skull fractures heal without treatment, as do most cases of CSF otorrhea.

PERIORBITAL REGION

The presence of bilateral periorbital ecchymosis is also a sign of basilar skull fracture. The globe should be auscultated, with a bruit indicating a possible carotid-cavernous sinus fistula (CC fistula). A CC fistula may also present with chemosis, proptosis, and orbital pain.

FACE/NOSE

The face should be examined for symmetry. A peripheral facial nerve injury presents as loss of motor function of both the upper and lower facial muscles. In central facial nerve palsy, only the lower face is typically affected. The nose should be examined for signs of CSF rhinorrhea.

CAROTID ARTERY

The carotid artery should be palpated and auscultated. A palpable thrill or audible bruit can be an indication of a carotid dissection and can also be seen in carotid stenosis. Hemiparesis or hemiplegia after trauma, even in the absence of the above findings, should prompt a search for possible carotid artery dissection.

CERVICAL SPINE

As mentioned previously, it is assumed that every trauma patient has a cervical spine injury until proven otherwise. In the awake, alert, non-intoxicated patient who denies neck pain or tenderness and has no distracting injuries, the patient’s cervical spine can be cleared without radiographs. In all other trauma patients, the cervical spine should be cleared using a combination of radiographs and physical examination.

OPTIC NERVE FUNCTION

In the awake and alert patient, the ocular nerve can be quickly assessed by having the patient finger count or by having the patient read text or using a vision screening card. In the unconscious person, the pupil can be examined and indirectly give some information regarding the function of the optic nerve.

PUPILS

The pupils should be examined for symmetry, diameter, and reactivity to light (both the direct and consensual response).

Afferent Pupillary Defect.

This is assessed using the swing flashlight test. When the light is moved swiftly back and forth from the right to left eye, the pupils should remain the same size. If the right pupil enlarges with direct light and constricts with light shone into the left eye (consensual response), this indicates a right optic nerve injury.

Traumatic Pupil.

This is seen in cases of trauma to the eye and can result in miosis or mydriasis. In cases of mydriasis, it can be difficult to differentiate from a third nerve palsy. A head CT scan is typically obtained in this patient population to ensure there is no intracranial pathology explaining the pupillary abnormality.

Third Nerve Palsy.

A third nerve palsy in the trauma patient will typically present as unilateral dilated pupil that does not respond to light (direct or consensual response). The eye is typically displaced laterally as the medial rectus is weakened. It is typically seen on the side ipsilateral to the intracranial mass lesion. The patient will most often have hemiparesis or hemiplegia opposite the side of the lesion. In about 15% of the cases, the dilated pupil from a third nerve palsy will be ipsilateral to the weakness as the contralateral cerebral peduncle is compressed by the tentorial notch (Kernohan’s phenomenon).

EXTRAOCULAR MUSCLES

The patient should be examined for eye movement in each possible direction. Following are the more commonly found abnormalities in trauma.

Unilateral Lateral Gaze Palsy.

The sixth nerve (abducens) controls the function of the lateral rectus muscle. Injury to the sixth nerve results in the inability to abduct the ipsilateral eye during extraocular motion testing. It can be a false localizing sign since it may be seen in cases of indirect compression (elevated intracranial hypertension) but can also be seen in direct compression of the sixth nerve. The sixth nerve has a long intracranial course, which some postulate makes it more sensitive to elevated intracranial pressure.

Paresis of Upward Gaze.

Parinaud’s syndrome is most classically seen with pineal region lesions, but can also be seen in instances of hydrocephalus or compression of the midbrain tectum. In these cases, there is often paresis of upward gaze, lid retraction, non-reactive pupils, and lack of convergence.

OCULOVESTIBULAR AND OCULOCEPHALIC REFLEXES

Cold water caloric testing and oculocephalic testing are not typically undertaken in the initial assessment of the trauma patient. Oculocephalic testing is contraindicated in patients with possible cervical spine injury.

CORNEAL REFLEX

The corneal response is assessed by lightly stroking the surface of the globe with a wisp of cotton. The normal response is to close the eye. This tests both first division of CN V (sensation of the cornea) and CN VII (closing the eye). Absence of the corneal reflex is often seen with a pontine injury.

GAG REFLEX

The gag reflex is elicited by stroking the wall of the pharynx. The gag reflex is mediated by CN IX (sensory) and CN X (motor) nerves. Absence of the gag response would suggest injury in the region of the medulla.

MOTOR EXAMINATION

The initial assessment should ensure that the patient has equal and normal strength in the upper and lower extremities. The tone of the muscles should also be assessed (flaccid vs. normal or increased tone). Hemiparesis with facial involvement would suggest a hemispheric brain injury or carotid artery injury. Hemiparesis without facial involvement would be more likely seen in an incomplete spinal cord injury. Quadriplegia or paraplegia most typically corresponds with a spinal cord injury and can often be localized clinically with further muscle and sensory testing. In the unconscious patient, the strength can be assessed by applying a noxious stimulus to each extremity (nailbed pressure) and observing for appropriate withdrawal.

REFLEXES

The reflexes should be rapidly assessed in the trauma patient. A preserved or hyperactive reflex in the setting of a flaccid limb would indicate a central nervous system trauma, whereas a flaccid limb with an absent reflex would indicate a nerve or spinal cord injury. Upgoing toes (Babinski reflex) would also indicate a central nervous system trauma and would be absent in a nerve or spinal cord injury.

SENSORY EXAMINATION

In the conscious patient, sensation is assessed by testing for light touch and pinprick on the trunk and all four extremities along with position sense in the lower extremities. In the unconscious patient, the noxious stimulus used to check motor function also gives some insight into the patient’s sensory function.

ASSOCIATED ABNORMALITIES

Special attention should also be given to the following regions when evaluating the patient with a possible neurologic injury.

SCALP

The scalp is a very vascular structure. A laceration can lead to significant blood loss. The entire scalp should be examined for lacerations. Logroll precautions should be used until the spine has been cleared (radiographically and/or clinically).

AURICULAR/PERIAURICULAR REGION

Battle’s sign is ecchymosis behind the ear and is typically associated with a basilar skull fracture. The external auditory canal should also be inspected for laceration and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) drainage; both can be seen with basilar skull fractures. The tympanic membrane should be inspected when possible. Blood seen behind the tympanic membrane is also an indication of a possible basilar skull fracture. The great majority of skull fractures heal without treatment, as do most cases of CSF otorrhea.

PERIORBITAL REGION

The presence of bilateral periorbital ecchymosis is also a sign of basilar skull fracture. The globe should be auscultated, with a bruit indicating a possible carotid-cavernous sinus fistula (CC fistula). A CC fistula may also present with chemosis, proptosis, and orbital pain.

FACE/NOSE

The face should be examined for symmetry. A peripheral facial nerve injury presents as loss of motor function of both the upper and lower facial muscles. In central facial nerve palsy, only the lower face is typically affected. The nose should be examined for signs of CSF rhinorrhea.

CAROTID ARTERY

The carotid artery should be palpated and auscultated. A palpable thrill or audible bruit can be an indication of a carotid dissection and can also be seen in carotid stenosis. Hemiparesis or hemiplegia after trauma, even in the absence of the above findings, should prompt a search for possible carotid artery dissection.

CERVICAL SPINE

As mentioned previously, it is assumed that every trauma patient has a cervical spine injury until proven otherwise. In the awake, alert, non-intoxicated patient who denies neck pain or tenderness and has no distracting injuries, the patient’s cervical spine can be cleared without radiographs. In all other trauma patients, the cervical spine should be cleared using a combination of radiographs and physical examination.

OPTIC NERVE FUNCTION

In the awake and alert patient, the ocular nerve can be quickly assessed by having the patient finger count or by having the patient read text or using a vision screening card. In the unconscious person, the pupil can be examined and indirectly give some information regarding the function of the optic nerve.

PUPILS

The pupils should be examined for symmetry, diameter, and reactivity to light (both the direct and consensual response).

Afferent Pupillary Defect.

This is assessed using the swing flashlight test. When the light is moved swiftly back and forth from the right to left eye, the pupils should remain the same size. If the right pupil enlarges with direct light and constricts with light shone into the left eye (consensual response), this indicates a right optic nerve injury.

Traumatic Pupil.

This is seen in cases of trauma to the eye and can result in miosis or mydriasis. In cases of mydriasis, it can be difficult to differentiate from a third nerve palsy. A head CT scan is typically obtained in this patient population to ensure there is no intracranial pathology explaining the pupillary abnormality.

Third Nerve Palsy.

A third nerve palsy in the trauma patient will typically present as unilateral dilated pupil that does not respond to light (direct or consensual response). The eye is typically displaced laterally as the medial rectus is weakened. It is typically seen on the side ipsilateral to the intracranial mass lesion. The patient will most often have hemiparesis or hemiplegia opposite the side of the lesion. In about 15% of the cases, the dilated pupil from a third nerve palsy will be ipsilateral to the weakness as the contralateral cerebral peduncle is compressed by the tentorial notch (Kernohan’s phenomenon).

EXTRAOCULAR MUSCLES

The patient should be examined for eye movement in each possible direction. Following are the more commonly found abnormalities in trauma.

Unilateral Lateral Gaze Palsy.

The sixth nerve (abducens) controls the function of the lateral rectus muscle. Injury to the sixth nerve results in the inability to abduct the ipsilateral eye during extraocular motion testing. It can be a false localizing sign since it may be seen in cases of indirect compression (elevated intracranial hypertension) but can also be seen in direct compression of the sixth nerve. The sixth nerve has a long intracranial course, which some postulate makes it more sensitive to elevated intracranial pressure.

Paresis of Upward Gaze.

Parinaud’s syndrome is most classically seen with pineal region lesions, but can also be seen in instances of hydrocephalus or compression of the midbrain tectum. In these cases, there is often paresis of upward gaze, lid retraction, non-reactive pupils, and lack of convergence.

OCULOVESTIBULAR AND OCULOCEPHALIC REFLEXES

Cold water caloric testing and oculocephalic testing are not typically undertaken in the initial assessment of the trauma patient. Oculocephalic testing is contraindicated in patients with possible cervical spine injury.

CORNEAL REFLEX

The corneal response is assessed by lightly stroking the surface of the globe with a wisp of cotton. The normal response is to close the eye. This tests both first division of CN V (sensation of the cornea) and CN VII (closing the eye). Absence of the corneal reflex is often seen with a pontine injury.

GAG REFLEX

The gag reflex is elicited by stroking the wall of the pharynx. The gag reflex is mediated by CN IX (sensory) and CN X (motor) nerves. Absence of the gag response would suggest injury in the region of the medulla.

MOTOR EXAMINATION

The initial assessment should ensure that the patient has equal and normal strength in the upper and lower extremities. The tone of the muscles should also be assessed (flaccid vs. normal or increased tone). Hemiparesis with facial involvement would suggest a hemispheric brain injury or carotid artery injury. Hemiparesis without facial involvement would be more likely seen in an incomplete spinal cord injury. Quadriplegia or paraplegia most typically corresponds with a spinal cord injury and can often be localized clinically with further muscle and sensory testing. In the unconscious patient, the strength can be assessed by applying a noxious stimulus to each extremity (nailbed pressure) and observing for appropriate withdrawal.

REFLEXES

The reflexes should be rapidly assessed in the trauma patient. A preserved or hyperactive reflex in the setting of a flaccid limb would indicate a central nervous system trauma, whereas a flaccid limb with an absent reflex would indicate a nerve or spinal cord injury. Upgoing toes (Babinski reflex) would also indicate a central nervous system trauma and would be absent in a nerve or spinal cord injury.

SENSORY EXAMINATION

In the conscious patient, sensation is assessed by testing for light touch and pinprick on the trunk and all four extremities along with position sense in the lower extremities. In the unconscious patient, the noxious stimulus used to check motor function also gives some insight into the patient’s sensory function.

DETAILED EVALUATION

After the rapid initial assessment and neurologic examination, attention can be turned to a more thorough examination. If possible, at this time a full history including review of systems, family medical history, and social history is obtained. If the patient has not had a thorough head-to-toe check by the emergency room or trauma physician, this should be completed. A detailed neurologic examination to assess for more subtle deficits can then be undertaken and is described below.

MENTAL STATUS

At this point, a more thorough evaluation of the patient’s mental status can be undertaken. Short-term memory can be assessed by giving the patient three items to remember and asking him or her to repeat the items after 5 minutes. Concentration can be assessed by asking the patient to spell “world” backwards.

CRANIAL NERVE EXAMINATION

Cranial Nerve I (Olfactory Nerve)

The sense of smell is tested bilaterally. A familiar, non-noxious (i.e., ammonia) scent should be used (e.g., coffee). Patients with fractures through the cribriform plate will often have loss of smell either unilaterally or bilaterally. CSF rhinorrhea as mentioned earlier can also be seen with fractures involving the cribriform plate and should prompt a more thorough examination of the patient’s sense of smell.

Cranial Nerve II (Optic Nerve)

A more thorough vision screening may be performed at this point. If not performed earlier, the patient’s visual acuity is assessed with a vision screener. If the patient cannot read, the patient should be asked if he or she is able to discern movement or light. If the patient routinely wears glasses, these should be used if available. In addition to visual acuity, the patient’s visual fields should be assessed with gross confrontation. A loss in peripheral vision can be seen with multiple injuries, including the optic chiasm or occipital lobe.

The function of the pupil was assessed in the initial evaluation. At this point, the fundus should be examined using an ophthalmoscope. The pupil is not typically chemically dilated in the trauma patient since this will cause the pupil to remain dilated for several hours and would cause the examiner to lose an important sign of a potentially serious problem (increasing mass lesion in the brain). Papilledema is not typically seen in acute trauma but can be seen 24-48 hours after the development of elevated intracranial pressure.

Cranial Nerves III, IV, and VI (Oculomotor, Trochlear, and Abducens)

The patient’s extraocular motions should be checked thoroughly by having the patient follow the examiner’s hand in each direction. The trochlear nerve controls the superior oblique muscle and the abducens nerve controls the lateral rectus muscle. The remainder of the extraocular muscles are controlled by the oculomotor nerve, which also controls pupillary constriction. The eyes should move symmetrically and smoothly. The patient should be questioned as to whether he or she has diplopia at any time, particularly with extremes of gaze. Diplopia is seen with any slight malalignment of the patient’s eyes and can be a sign of dysfunction of the cranial nerve. Diplopia is corrected by asking the patient to cover one eye in all cases related to optic nerve injury. If diplopia persists after covering one eye, it is likely related to a problem with the eye itself (e.g., cataract).

Cranial Nerve V (Trigeminal)

The trigeminal nerve has three divisions that give sensation to the face with the exception of the angle of the jaw. The ophthalmic branch gives sensation to the majority of the scalp and to just below the eye, the maxillary branch gives sensation over the region of the maxillary sinus, and the mandibular branch gives sensation over the mandible. This should be assessed in each division using pinprick. As mentioned previously, the trigeminal nerve along with the facial nerve comprise the corneal reflex. The trigeminal nerve also supplies motor function to the muscles of mastication and sensation to the anterior two thirds of the tongue.

Cranial Nerve VII (Facial)

The facial nerve supplies innervation to the muscles of facial expression and assists in closing the eyelid. In the initial evaluation of the face, symmetry was assessed. A peripheral facial nerve injury (lower motor neuron) presents as loss of motor function of both the upper and lower facial muscles. In central facial nerve palsy (upper motor neuron), only the lower face is typically affected. Therefore, with an intracranial mass lesion, one would expect to see a contralateral paresis of the lower face only (the forehead will still wrinkle while the eyes are opened widely).

Cranial Nerve VIII (Vestibulocochlear)

The vestibulocochlear nerve helps control hearing and equilibrium. The function of the nerve is checked by the examiner rubbing his or her fingers gently by the patient’s ear or whispering. There are two types of hearing deficit: conductive and sensorineural. A conductive lesion is seen with lesions that interfere with movement of the ossicles. This could occur with blood in the canal or fluid behind the tympanic membrane in the setting of trauma. With Rinne testing, the bone conduction will be greater than the air conduction, and with Weber testing, the loudest sound will lateralize to the side of the hearing loss. Sensorineural loss is seen in cases of cochlear damage or nerve injury. With sensorineural loss, air conduction is greater than bone conduction and the Weber test will lateralize to the side of better hearing.

Cranial Nerves IX and X (Glossopharyngeal and Vagus)

The gag reflex was previously assessed. Additional testing of these nerves would involve asking the patient to open his or her mouth and repeat “Ahh.” The uvula will deviate away from the side of the lesion if present.

Cranial Nerve XI (Spinal Accessory)

This is assessed by asking the patient to raise his or her shoulders bilaterally and checking the integrity of the sternocleidomastoid bilaterally.

Cranial Nerve XII (Hypoglossal)

The hypoglossal nerve is responsible for protrusion of the tongue. An injury to the hypoglossal nerve would cause the tongue to deviate to the side of the lesion since only the contralateral side of the tongue would protrude.

MOTOR SYSTEM

The major muscle groups should be assessed for power. The muscle is typically graded on a scale from 0 to 5.

| 0 | No contraction |

| 1 | Flicker of movement |

| 2 | Movement with gravity eliminated |

| 3 | Anti-gravity strength |

| 4 | Movement against resistance |

| 5 | Normal strength |

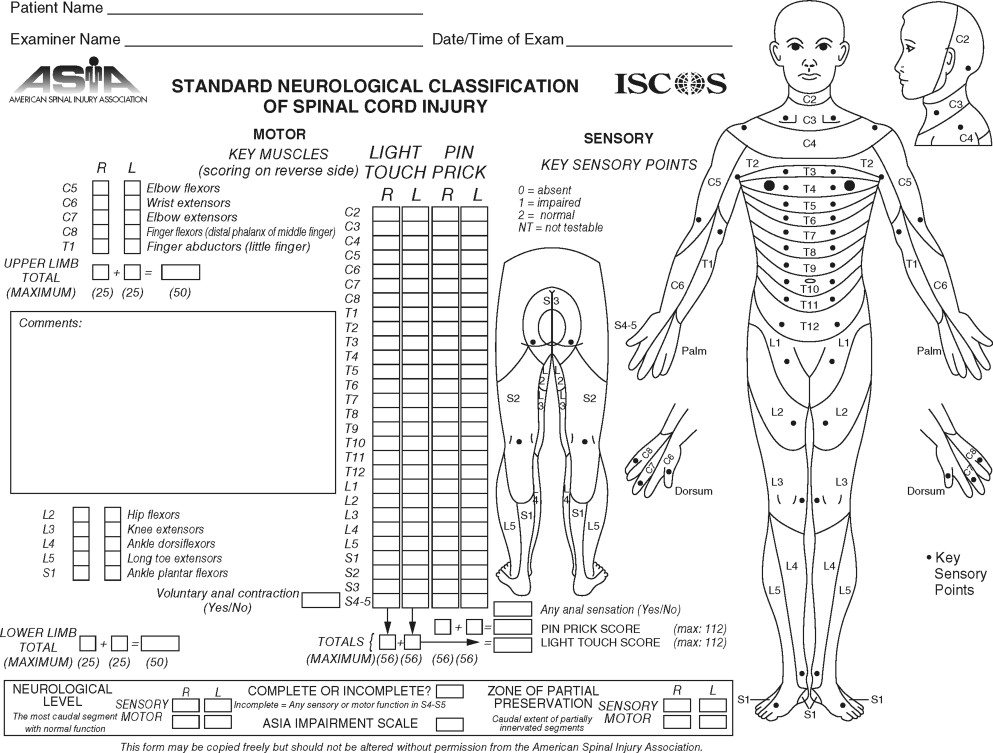

The American Spinal Injury Association (ASIA) Standard Neurological Classification of Spinal Cord Injury form is an excellent resource available free of charge and includes the muscle groups typically assessed and correlates them with the level of injury ( Figure 5-1 ).

SENSORY SYSTEM

The patient should be assessed for bilateral light touch and pinprick sensation. The ASIA form includes a very nice dermatome chart and correlates levels of sensory abnormality with level of injury in the spinal cord.

CEREBELLAR FUNCTION

Multiple tests can assess cerebellar function. Finger-nose-finger, heel-to-shin, rapid alternating movement, and finger tapping all assess the function of the cerebellum. Abnormalities typically present ipsilaterally to the side of the lesion. Gait should be assessed if possible. With cerebellar injury the patient tends to fall to the side of the lesion.

GRADING THE SEVERITY OF INJURY

GLASGOW COMA SCALE

The severity of neurologic injury in the trauma setting is most commonly assessed during the initial physical examination by using the GCS. It can be assessed in less than 30 seconds and has become the gold standard of coma scoring among trauma physicians and neurosurgeons. The GCS has three components: eye, motor, and verbal, each of which are assigned points individually and then are added together to get the total GCS score. The GCS score can range from 3 (worst) to 15 (best). Severe head injury is denoted by a sum of 3 to 8, moderate head injury is denoted from 9 to 12, and mild head injury is between 13 and 15 in the non-intubated patient. If the patient is intubated, the eye and motor portions of the scale are assessed only and a “T” is denoted after the verbal portion, which is arbitrarily assigned 1 point since the patient cannot obviously speak while intubated. Prior to performing the examination, the examiner must also assess whether the patient has been recently chemically paralyzed and/or sedated for intubation or other reasons, since this would obviously iatrogenically reduce the coma score. Keep in mind too that when this score is used to assess the severity of neurologic injury, it generally refers to the best GCS of the patient that was taken after adequate hemodynamic resuscitation and within the first few hours of injury ( Table 5-1 ).

| Eye Opening (E) | Verbal Response (V) | Motor Response (M) |

|---|---|---|

| 4 = Spontaneous | 5 = Normal conversation | 6 = Normal |

| 3 = To voice | 4 = Disoriented conversation | 5 = Localizes to pain |

| 2 = To pain | 3 = Words, but not coherent | 4 = Withdraws to pain |

| 1 = None |

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses