Damage to the sensory nerves supplying the jaws can occur in a number of ways during the course of dental treatment. The nerves involved can be the maxillary division of the trigeminal nerve, terminating in the dental branches and the infraorbital nerve; the mandibular division of the trigeminal nerve, terminating in the lingual nerve; the inferior alveolar nerve and its branches; and the long buccal nerve. Most attention has been devoted to the inferior alveolar and lingual nerves, because these appear to be the nerves most commonly involved in routine dental treatment and the ones that cause patients the most problems. Injury to the maxillary nerve, in particular, is more likely to result from trauma, orthognathic surgery, or other major surgery.

Involvement of the inferior alveolar and lingual nerve can occur from a number of dental causes including:

- 1

Inferior alveolar nerve blocks

- 2

Root canal therapy

- 3

Dentoalveolar surgery including:

- •

Implant placement

- •

Tooth removal (principally third molars)

- •

Periodontal surgery

- •

Inferior Alveolar Nerve Blocks

Although long-term injury has occasionally been described from other types of local anesthetic injection, it is most commonly described following an inferior alveolar nerve block. The true incidence is unknown, but permanent injury may occur in around 1 in 25,000 inferior alveolar nerve blocks. When it occurs, most patients appear to recover fully, and it has been estimated that about 85% of patients will recover completely within 8 to 10 weeks, another 5% will recover over a longer period, and 10% will be permanently injured. The exact etiology of the injury is unknown because only about half of the patients are aware of the electric shock sensation when the injection is given; the lingual nerve is predominantly affected, and in a disproportionate number of the permanent cases, dysesthesia is the presenting factor, unlike traumatic nerve injuries. All local anesthetics appear to have the potential to cause this problem, and currently no therapy appears to be effective. In the small number of patients who have undergone surgical exploration, most frequently no injury is seen, and therefore no type of repair surgery has been possible. There is no evidence that any vitamin or other supplements are effective, and because of the high incidence of dysesthesia in these cases, referral to a pain center frequently occurs. Steroids are sometimes given in the early phases in an attempt to suppress any inflammatory component, but there is no evidence that this is successful, particularly because steroids normally cannot be started for at least 24 hours after the causative injections—patients rarely inform their dentist prior to this period. To be effective, steroids would need to be given in the very early inflammatory phase. Some advocates recommend that steroids be injected locally, or oral steroids can be utilized in the form of a Dosepak of either dexamethasone or methylprednisolone.

Root Canal Therapy

Injury to the inferior alveolar nerve can occur when root canal therapy is carried out on mandibular teeth posterior to the mental foramen ( Fig. 33-1 ). It can be a purely mechanical injury with overinstrumentation through the apex of the tooth, but, in many cases, it represents a physicochemical injury from the sealant gaining access to the inferior alveolar nerve. All sealants currently in use appear to be neurotoxic, at least until they set. They thus have the ability to cause physicochemical damage to the inferior alveolar nerve, should they penetrate the epineurium and come into contact with the fascicles. There does appear to be variation in the time needed to cause permanent nerve damage, which can vary from a few minutes to 2 or 3 days, depending on the root canal sealant used. Because all sealants are radiopaque, their proximity to the inferior alveolar canal can be visualized on post–root canal therapy radiographs. If on completion of root canal therapy, the postoperative radiograph indicates that sealant may have gained access to the inferior alveolar canal, the patient should be carefully monitored for evidence of nerve involvement. This may not always be apparent once the local anesthetic wears off, because sensation may be normal for 24 or even 36 hours before paresthesia develops, depending on the root canal sealant used. If there is any evidence of nerve involvement, the sooner the root canal sealant is removed from the canal, the better is the chance of nerve recovery. Any surgery is normally carried out under general anesthesia, and, in most cases, it will require lateral decortication of the mandible, identification of the inferior alveolar canal, debridement of the canal and the epineurium itself, and careful replacement of the nerve in its canal after all sealant has been removed. If this is carried out within a short span of hours from when the damage becomes apparent, a good result can be anticipated. If it is left longer than this, any nerve damage may well be permanent, and the only curative treatment would be to resect the permanently damaged segment of nerve and insert a graft of some kind, because the damage normally covers an area too extensive to be treated by direct anastomosis of the nerve ends.

Root Canal Therapy

Injury to the inferior alveolar nerve can occur when root canal therapy is carried out on mandibular teeth posterior to the mental foramen ( Fig. 33-1 ). It can be a purely mechanical injury with overinstrumentation through the apex of the tooth, but, in many cases, it represents a physicochemical injury from the sealant gaining access to the inferior alveolar nerve. All sealants currently in use appear to be neurotoxic, at least until they set. They thus have the ability to cause physicochemical damage to the inferior alveolar nerve, should they penetrate the epineurium and come into contact with the fascicles. There does appear to be variation in the time needed to cause permanent nerve damage, which can vary from a few minutes to 2 or 3 days, depending on the root canal sealant used. Because all sealants are radiopaque, their proximity to the inferior alveolar canal can be visualized on post–root canal therapy radiographs. If on completion of root canal therapy, the postoperative radiograph indicates that sealant may have gained access to the inferior alveolar canal, the patient should be carefully monitored for evidence of nerve involvement. This may not always be apparent once the local anesthetic wears off, because sensation may be normal for 24 or even 36 hours before paresthesia develops, depending on the root canal sealant used. If there is any evidence of nerve involvement, the sooner the root canal sealant is removed from the canal, the better is the chance of nerve recovery. Any surgery is normally carried out under general anesthesia, and, in most cases, it will require lateral decortication of the mandible, identification of the inferior alveolar canal, debridement of the canal and the epineurium itself, and careful replacement of the nerve in its canal after all sealant has been removed. If this is carried out within a short span of hours from when the damage becomes apparent, a good result can be anticipated. If it is left longer than this, any nerve damage may well be permanent, and the only curative treatment would be to resect the permanently damaged segment of nerve and insert a graft of some kind, because the damage normally covers an area too extensive to be treated by direct anastomosis of the nerve ends.

Damage From Dentoalveolar Surgery

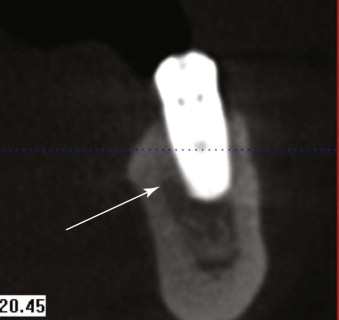

Dental Implants

Implant placement in the mandible posterior to the mental foramen carries a risk of involvement of the inferior alveolar nerve, and, if this is felt to be at risk and one still wishes to insert implants, then three-dimensional scanning of the mandible (cone beam computed tomography [CBCT]), followed by careful planning and the use of implant drills with a fixed and measured stop, may be indicated ( Fig. 33-2 ). When damage occurs, it is more likely due to the drilling process itself rather than the actual implant insertion so that withdrawal of the implant, if it is impinging on the nerve, is a sensible precaution but rarely relieves the symptoms if they were caused by the drilling process. Unfortunately, if the involvement is from the drilling, spontaneous recovery tends to be poor, because the area of damage can be fairly extensive. Surgery, however, equally does not give a very satisfactory result, because the damaged segment often has to be resected. Also, because of the extent of the damage, direct anastomosis is often not possible, meaning that a graft of some kind must be used with a subsequently lower success rate.

Dental Extractions (Most Commonly Third Molars)

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses