Introduction

In this study, we present a novel classification method for individual assessment of midpalatal suture morphology.

Methods

Cone-beam computed tomography images from 140 subjects (ages, 5.6-58.4 years) were examined to define the radiographic stages of midpalatal suture maturation. Five stages of maturation of the midpalatal suture were identified and defined: stage A, straight high-density sutural line, with no or little interdigitation; stage B, scalloped appearance of the high-density sutural line; stage C, 2 parallel, scalloped, high-density lines that were close to each other, separated in some areas by small low-density spaces; stage D, fusion completed in the palatine bone, with no evidence of a suture; and stage E, fusion anteriorly in the maxilla. Intraexaminer and interexaminer agreements were evaluated by weighted kappa tests.

Results

Stages A and B typically were observed up to 13 years of age, whereas stage C was noted primarily from 11 to 17 years but occasionally in younger and older age groups. Fusion of the palatine (stage D) and maxillary (stage E) regions of the midpalatal suture was completed after 11 years only in girls. From 14 to 17 years, 3 of 13 (23%) boys showed fusion only in the palatine bone (stage D).

Conclusions

This new classification method has the potential to avoid the side effects of rapid maxillary expansion failure or unnecessary surgically assisted rapid maxillary expansion for late adolescents and young adults.

Rapid maxillary expansion (RME) has been used in orthodontic practice for the correction of posterior crossbite and dental crowding as well as to facilitate correction of Angle Class II and Class III malocclusions, with the overall objective to widen the maxilla by separating the midpalatal suture and the circummaxillary sutural system.

Since the pioneering work of Angell 150 years ago that introduced the concept that the maxilla can be expanded by opening the midpalatal suture, the early orthodontic literature (1860-1930) included controversy as to whether it was possible to widen the hard palate at the midpalatal suture. The landmark work of Haas made RME routine in many orthodontic practices, beginning in the 1960s. However, details of the morphology and the maturation of the midpalatal suture have been investigated only in histologic studies, an autopsy microcomputed tomography study, an investigation with occlusal radiographs, and an animal study with multislice computed tomography.

Understanding individual variability in the fusion of the midpalatal suture is essential in identifying prospectively which late adolescent or young adult patient can have RME as a less-invasive alternative to surgically assisted expansion. The midpalatal suture has been described as an end-to-end type of suture with characteristic changes in its morphology during growth. In the infantile period, Melsen reported that the midpalatal suture is broad and Y-shaped in its frontal sections.

The ossification process in the midpalatal suture starts with bone spicules from suture margins along with “islands” (ie, masses of acellular tissue and inconsistently calcified tissue) in the middle of the sutural gap. The formation of spicules occurs in many places along the suture, with the number of spicules increasing with maturation and forming many scalloped areas that are close to each other and separated in some areas by connective tissue. Concomitantly, interdigitation increases ; then fusion occurs earlier in the posterior area of the suture, with progression of ossification taking place from posterior to anterior, with resorption of cortical bone in the sutural ends and formation of cancellous bone.

The start and the advance of fusion of the midpalatal suture vary greatly with age and sex. Persson and Thilander observed fusion of the midpalatal suture in subjects ranging from 15 to 19 years old. On the other hand, patients at ages 27, 32, 54, and even 71 years have been reported to have no signs of fusion of this suture. Such findings indicate that variability in the developmental stages of fusion of the midpalatal suture is not related directly to chronologic age, particularly in young adults.

For this reason, Revelo and Fishman proposed individual assessment of the midpalatal suture morphology with occlusal radiographs before RME therapy. However, occlusal radiographs are not reliable for analyzing midpalatal suture morphology because the vomer and the structures of the external nose overlay the midpalatal area and thus might lead to false radiographic interpretations of midpalatal suture fusion.

Cone-beam computed tomography (CBCT) provides 3-dimensional visualization of the oral and maxillofacial structures at relatively low cost, no superimposition of adjacent structures, easy accessibility, and low radiation exposure compared with multislice medical computed tomography. The aim of this study was to present a novel classification method for the individual assessment of midpalatal suture morphology using CBCT images because RME is an unpredictable treatment for late adolescent and young adult patients.

Material and methods

Baseline diagnostic CBCT images acquired for clinical purposes in 147 subjects were selected initially; however, 7 subjects were excluded because of poor-quality scans (eg, blurry images). CBCT scans from 140 subjects (86 female, 54 male; Table I ), with ages from 5.6 to 58.4 years and no history of previous orthodontic treatment, were examined to determine the radiographic stages of midpalatal suture maturation, as described in this study. All CBCT images were taken before orthodontic treatment for clinical reasons to aid in the diagnosis of clinical conditions such as canine impaction or skeletal malocclusion. Institutional review board approval for the study was obtained from the University of Michigan.

| Sex | 5-<11 y | 11-<14 y | 14-18 y | >18 y | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Female | 24 | 24 | 19 | 19 | 86 |

| Male | 4 | 24 | 13 | 13 | 54 |

| Total | 28 | 48 | 32 | 32 | 140 |

The CBCT scans images were obtained with an iCAT cone-beam 3-dimensional imaging system (Imaging Sciences International, Hatfield, Pa). Each subject was seated in an upright position with the Frankfort horizontal plane (superior aspect of the external auditory canal to infraorbital rim line) parallel to the ground during the scanning process. For all scans, the minimum field of view used was 11 cm, and the scan time ranged from 8.9 to 20 seconds with a resolution of 0.25 to 0.30 mm.

Image analysis was performed using Invivo5 (Anatomage, San Jose, Calif). The following steps were executed for determining and analyzing the maturational stages of the midpalatal suture.

- 1.

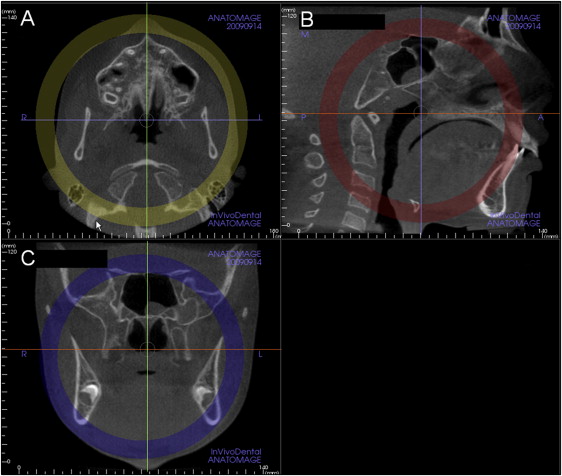

Head orientation. Natural head position in all 3 planes of space was verified or corrected. The cursor (the position indicator) of the image analysis software was positioned at the patient’s midsagittal plane in both the coronal and axial views ( Fig 1 ). In the sagittal view, the patient’s head was adjusted so that the anteroposterior long axis of the palate was horizontal.

Fig 1 Standardization of head position in the A , axial; B , sagittal, and C , coronal planes to allow consistent assessments of the midpalatal suture. Note that in B , the sagittal view, the orange line that indicates the position of the axial plane view is positioned through the center of the superoinferior dimension of the hard palate (Invivo5). - 2.

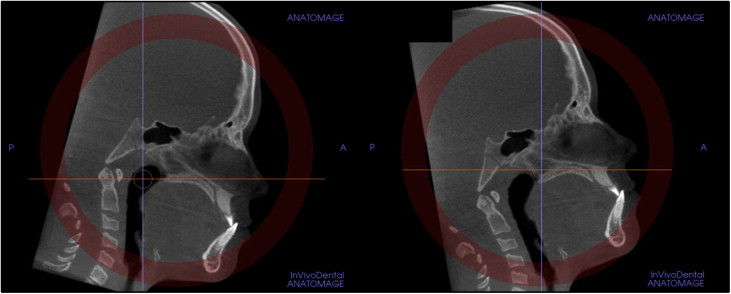

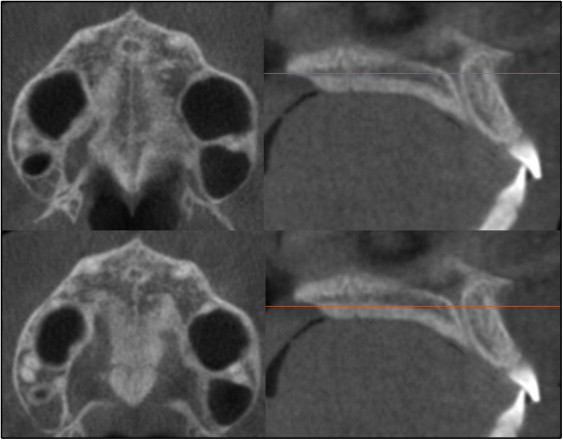

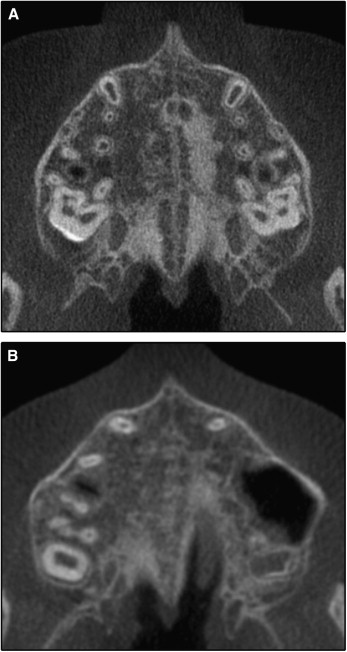

Standardization of the axial cross-sectional slice used for sutural assessment. In the sagittal plane, the midsagittal cross-sectional slice was used to position the palate horizontally, parallel to the software’s horizontal orange line ( Fig 1 , B ). After placing the horizontal line along the palate, the central cross-sectional slice in the superoinferior dimension (ie, from the nasal to the oral surface) was used for classification of the maturational stage of the midpalatal suture ( Fig 1 ). For subjects with a curved palate, the palate was evaluated in 2 central cross-sectional axial slices, identifying the posterior and anterior regions of the midpalatal suture separately ( Fig 2 ). For subjects with a thicker palate, the palate was evaluated in the 2 most central axial slices ( Fig 3 ). A curved palate was defined as a palate where the anterior and posterior portions cannot be visualized in the same axial slice, and the sutural staging classification requires 2 slices. A thick palate was defined as a palate where the midpalatal suture can be assessed in more than 3 axial slices (1 oral, 1 central, and 1 nasal); for this reason, a thick palate might have 2 or more central slices.

Fig 2 For subjects with a curved palate, 2 axial plane images through the posterior and anterior regions were used. The central cross-sectional slices along the axis of the palate in the anterior and posterior regions were evaluated.

Fig 3 For patients with a thick palate, the 2 most central axial slices were analyzed. - 3.

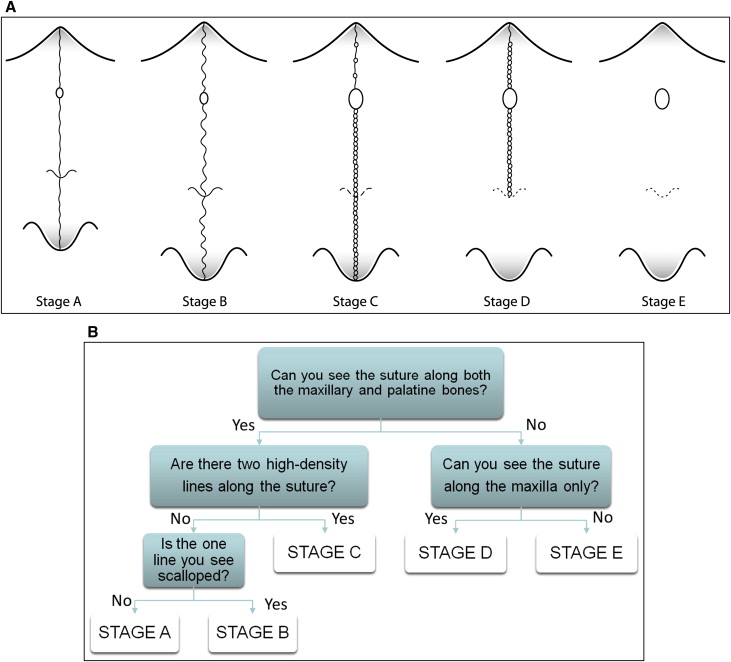

Definition of the maturational stages of the midpalatal suture. The stages of fusion of the midpalatal suture were described from the analysis of these standardized CBCT cross-sectional images in the axial plane by an orthodontist (F.A.) and an oral and maxillofacial radiologist (E.B.). The definition of each CBCT radiographic appearance of the sutural maturation stage followed the findings of unique morphology in the maturation of the midpalatal suture described in previous histologic studies. The radiographic aspect of the midpalatal suture from early infancy was observed as a high-density line or area even before sutural interdigitation and fusion. The following descriptive stages of midpalatal suture maturation are proposed ( Fig 4 , A and B ).

Fig 4 A , Schematic drawing of the maturation stages observed in the midpalatal suture. It is a simplification of the sutural morphology and should not be used for diagnosis. Sutural morphology can vary between stages, and diagnostic criteria are based on the decision tree in B and the definitions of the 5 stages. B , Decision tree for classification of the maturation stages of the midpalatal suture.

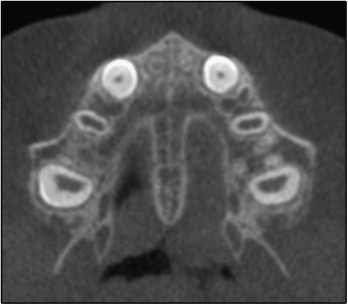

In stage A, the midpalatal suture is almost a straight high-density sutural line with no or little interdigitation ( Fig 5 ).

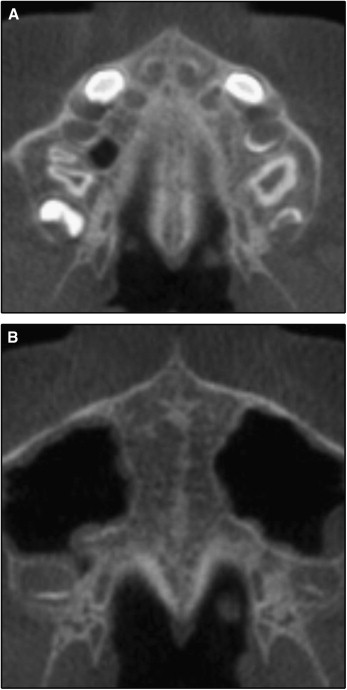

In stage B, the midpalatal suture assumes an irregular shape and appears as a scalloped high-density line ( Fig 6 , A ). Patients at stage B can also have some small areas where 2 parallel, scalloped, high-density lines close to each other and separated by small low-density spaces are seen ( Fig 6 , B ).

In stage C, the midpalatal suture appears as 2 parallel, scalloped, high-density lines that are close to each other, separated by small low-density spaces in the maxillary and palatine bones (between the incisive foramen and the palatino-maxillary suture and posterior to the palatino-maxillary suture). The suture can be arranged in either a straight or an irregular pattern ( Fig 7 , A and B ).

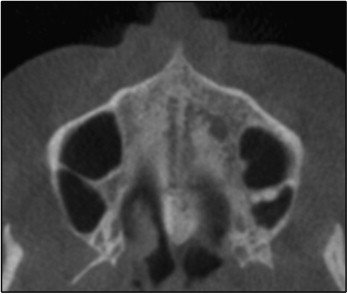

In stage D, the fusion of the midpalatal suture has occurred in the palatine bone, with maturation progressing from posterior to anterior. In the palatine bone, the midpalatal suture cannot be visualized at this stage, and the parasutural bone density is increased (high-density bone) compared with the density of the maxillary parasutural bone. In the maxillary portion of the suture, fusion has not yet occurred, and the suture still can be seen as 2 high-density lines separated by small low-density spaces ( Fig 8 ).

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses