Microbiology in endodontic therapy

Publisher Summary

The most common diseases that affect the dental pulp and periapical tissues are caused by bacteria. The sources and routes of infection that involve pulp and periapical tissues are: (1) carious dentine via dentinal tubules; (2) subgingival plaque bacteria present in deep periodontal pockets via lateral canals normally present in the apical two thirds of teeth; (3) from the oral environment secondary to tooth fracture or mechanical exposure; and (4) anachoresis—a mechanism whereby diseased tissue attracts bacteria present in bacteraemias. The clinical presentation and severity of these infections are related to the way in which the host defenses interact with the infective agents that are present in the pulp cavity. The initial defense mechanism of the pulp to infection is to prevent access of microorganisms to host tissues by depositing sclerotic or irregular secondary dentine in their pathway. Within the pulp, acute inflammation with phagocytosis might also occur, especially in the early stages of invasion, and later a chronic response might supervene with associated antibody-mediated immune reactions.

Pathogenesis of pulp and periapical infections

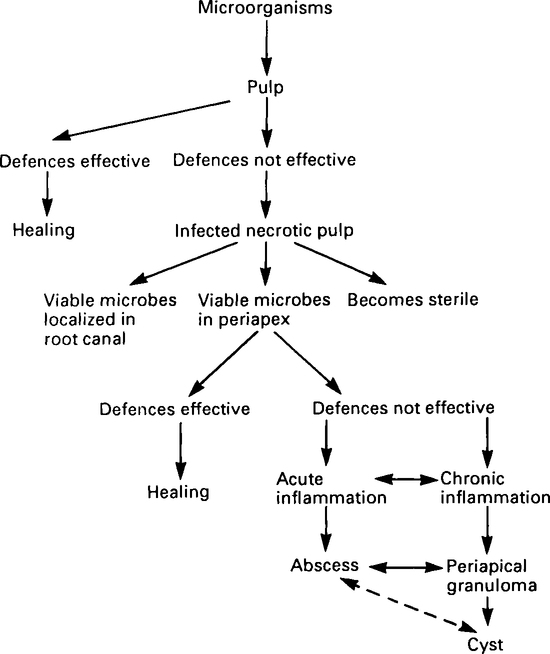

The clinical presentation and severity of these infections are related to the way in which the host defences interact with the infective agents present in the pulp cavity. An overall scheme of the stages involved in the spread of microorganisms from the pulp into the periapical tissues and possible sequelae are shown in Figure 7.1. Once bacteria gain access and proliferate in the pulp, it is unusual for the host defences to completely eliminate them. As a result, healing of infected pulp tissue is uncommon. The time necessary for complete necrosis of the pulp to take place is very variable; localized chronic infection may be present for many months or even years before the pulp dies. During this process the pulp may become sterile, especially if the carious cavity has been restored and the apical foramen occluded by calcified tissue. Usually viable microorganisms can be isolated from necrotic pulp tissue and they may either remain localized in the root canal or spread into the periapical tissues via the apical foramen or lateral root canals. It is not entirely clear if periapical granulomas develop in response to the presence of viable bacteria in the periapical tissues or if they form as a reaction to sterile, toxic products leaking from necrotic pulp tissue via the periapical foramen. However, recent studies suggest that the majority of granulomas contain relatively small numbers of bacteria which appear to be located within small areas of necrosis randomly scattered throughout the lesion. Little is known about the role, if any, of microorganisms in the development of periapical cysts. Dental cysts without any obvious pathway to the oral environment can become infected and it is possible that, in these cases, bacteria within the cyst itself proliferate due to alteration in the host–parasite relationship.

Microbiology

The main groups of bacteria related to pulp and dentoalveolar infections are shown in Table 7.1. Generally the microflora associated with these infections are similar but different to that present in carious dentine. Since carious dentine is believed to be the main source of bacteria which infect necrotic pulp tissue, it is surprising that such differences occur. One likely explanation is that over a period of time complex interactions occur between the different species which enter the pulp via carious dentine. Perhaps with time the environment of the necrotic pulp may favour the very small numbers of strictly anaerobic bacteria derived from dentine and thus allow them subsequently to proliferate, and predominate.

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses