This case report describes the treatment of a 25-year-old woman with a Class II malocclusion, secondary to mandibular skeletal deficiency, and mild overclosure. Inferior surgical repositioning of the maxilla is often the treatment of choice for patients with maxillary vertical deficiency; however, this patient had borderline vertical deficiency that was treated with a mandibular “tripod” advancement (leveling of the mandibular arch after surgery) coupled with a setback and down-grafting genioplasty. The surgical-orthodontic treatment plan, combined with cosmetic dentistry, resulted in dramatically improved facial esthetics and occlusal relationships.

Optimal treatment for an adult with mandibular anteroposterior deficiency and maxillary vertical deficiency (short lower anterior face height) can include mandibular advancement and maxillary down-graft osteotomies. However, for those with mandibular anteroposterior deficiency, borderline vertical deficiency, and normal incisal display, a decision might be made to advance the mandible only and forego the maxillary down-graft osteotomy. In this latter case, it can still be advantageous to maximize an increase in the lower anterior face height as the mandible is advanced surgically.

How can this be done? Jacobs and Sinclair suggested that, for vertically overclosed deepbite patients, leveling of the mandibular occlusal plane might be best after surgery. In this way, the mandibular incisors (not intruded preoperatively) are carried down the lingual surfaces of the maxillary incisors more during the surgical advancement than if they had been intruded preoperatively. Because the curve of Spee is not leveled preoperatively, at surgery, the advanced dentition contacts at only the anterior and most posterior tooth on each side. Hence, the common name for the procedure is “tripod” advancement. Postoperatively, the posterior teeth can be brought into occlusion by extrusion. We are unaware of any case report that demonstrates this concept. The purpose of this report is to present such a case.

Diagnosis and etiology

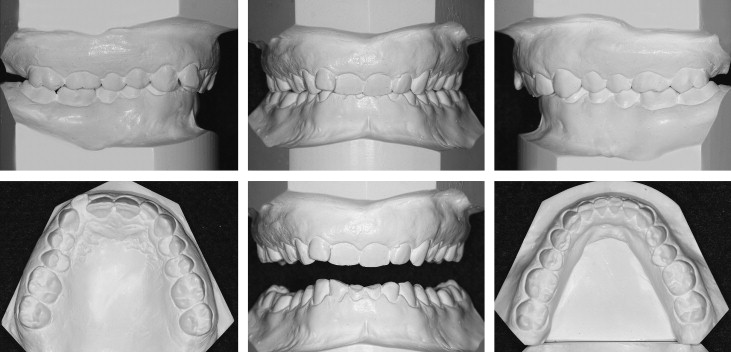

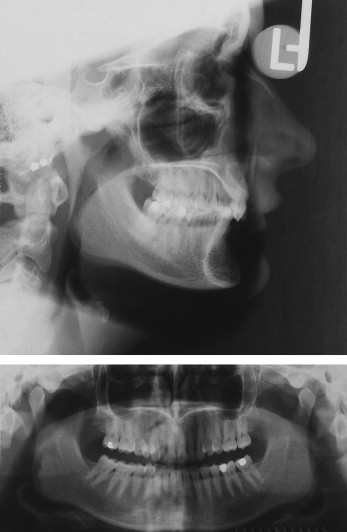

A 25-year-old white woman came to the orthodontic clinic at the University of Iowa in Iowa City, concerned about her smile ( Figs 1-5 ). Her medical history showed no contraindications to treatment. She had suffered trauma to her maxilla and incisors and had previously undergone orthodontic therapy. Her third molars had been extracted.

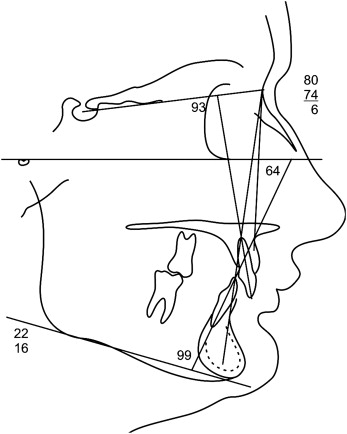

Clinical and radiographic examinations showed an Angle Class II Division 2 malocclusion, a convex profile with mandibular skeletal retrusion (ANB angle, 6°), short vertical proportions (short lower anterior face height), low mandibular plane angle, adequate soft tissues and bony pogonion, everted lower lip, deep labiomental sulcus, obtuse lip-chin-throat angle, and maxillary dental retrusion. Severe attrition of the maxillary and mandibular anterior teeth was noted. The maxillary anterior teeth had supraerupted, leading to excessive gingival display when smiling. Her overbite was 100%, and overjet was 1 mm. The maxillary dental midline was 1 mm to the right, the maxillary tooth size-arch length discrepancy was –3 mm, the curve of Spee was moderate, and there was no evidence of a shift from centric relation to centric occlusion. Examination of the temporomandibular joint showed an asymptomatic, anterior-displaced disc with reduction (popping) on the left side and deviation to the right on opening.

Treatment objectives

Our goals were to improve the patient’s facial esthetics and provide a harmonious occlusion. Facial treatment objectives included decreasing overall facial convexity, softening the chin projection, decreasing the labiomental sulcus depth, and increasing the lower anterior face height. Dental treatment objectives were to correct her Class II molar and canine relationships, correct her deepbite, reduce her excessive gingival display, and level, align, and coordinate her dental arches.

Treatment objectives

Our goals were to improve the patient’s facial esthetics and provide a harmonious occlusion. Facial treatment objectives included decreasing overall facial convexity, softening the chin projection, decreasing the labiomental sulcus depth, and increasing the lower anterior face height. Dental treatment objectives were to correct her Class II molar and canine relationships, correct her deepbite, reduce her excessive gingival display, and level, align, and coordinate her dental arches.

Treatment alternatives

In a recent study at the University of Iowa, patients who initially had an ANB angle equal to or greater than 6° were consistently judged by laypersons to have profile improvement after mandibular advancement surgery. In contrast, profiles of patients who initially had an ANB angle less than 6° were sometimes judged to be improved and sometimes not improved after surgery. From this study, the profile of our patient was predicted to be improved after mandibular advancement osteotomy.

Although a nonsurgical option of masking the underlying apical base discrepancy (headgear or extraction of first maxillary premolars) was presented to the patient as an alternative, the resulting esthetic outcome was not recommended. Instead, she chose an orthodontic-surgical solution. Additionally, because of her borderline short lower anterior face height, a decision was made to address the vertical dimension.

The final nonextraction treatment plan consisted of composite restoration of the mandibular incisors to facilitate bonding, placement of fixed orthodontic appliances, and alignment of the arches. The curve of Spee would not be leveled to prevent intruding the mandibular incisors. Surgery would consist of a mandibular “tripod” advancement to maximize lower anterior face height and a genioplasty setback to reduce her chin projection. Hoffman and Moloney suggested that posterior positioning of the chin is a reliable procedure to soften the chin projection after mandibular advancement, particularly in a patient with a Class II Division 2 malocclusion.

Additionally, we considered the anterior mandibular height and its contribution to our patient’s vertically deficient face. This dimension of the mandible is often overlooked. The sliding setback genioplasty has the advantage of softening pogonion and slightly increasing the vertical dimension of the lower face. An alternative option would have been genioplasty with an anteriorly tapered osteotomy, but this type of genioplasty, while decreasing chin projection, does not alter the anterior vertical height of the mandible. After surgery, the mandibular occlusal plane would be leveled by extrusion of the premolars and the first molars with vertical elastics, alleviating the need to overcome the heavy bite forces typical of a deepbite patient.

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses