11 Management of the permanent dentition

Tooth–arch size problems

Crowding

Mild crowding

Molar distalization

Moving the first permanent molars distally can create space. This is technically difficult in the mandibular arch and rarely attempted, but it is possible in the maxilla and appropriate for mild crowding, where the buccal segment relationship is up to half a unit class II. The most predictable technique, with the least associated anchorage loss, is extraoral traction mediated by the wearing of headgear (Fig. 11.1) (Sfondrini et al, 2002).

The biggest problems with the use of headgear are the dependence upon good compliance and favourable growth for success. In an attempt to overcome problems associated with compliance, numerous appliances have been designed to distalize the maxillary buccal segments without the need for headgear and are accordingly described as ‘non-compliance’ appliances. Most use the palate for anchorage, with a distalizing force applied directly to the maxillary first molars via either palatal springs or compressed coils. Although effective, all will tip the molars to some extent and result in anchorage loss in the form of an increase in overjet. To avoid this, implants can be used to support the anchorage further and these have been shown to be effective (Fig. 11.2) (Sandler et al, 2008).

Maintenance of the leeway space

The greater mesiodistal dimension of the second deciduous molars in comparison to the second premolar teeth can provide some additional space for the relief of crowding (Brennan & Gianelly, 2000). This can be done if the position of the first permanent molars is held just prior to exfoliation of the deciduous molars by fitting a lingual arch (see Figs 9.19 and 10.3). In the mandibular arch this provides approximately 2 to 2.5-mm of space per quadrant and in the maxilla around 1 to 1.5-mm.

Lip bumper

A lip bumper is a mandibular fixed appliance consisting of a 1.0-mm stainless steel wire attached to bands cemented to the first permanent molars. The wire passes along the buccal and labial sulci of the dentition, so that the labial portion sits in front of the lower incisors (Fig. 11.3). The wire can be encased in acrylic to increase its dimensions and is positioned so that the pressure normally applied to the mandibular dentition from the lower lip and cheeks is now applied to the appliance. This results in:

Interproximal enamel reduction

The removal of enamel from the interproximal regions can also be used to generate up to 1-mm of space per contact point in the buccal segments and 0.75-mm in the labial segments (Sheridan, 1985). This can be an effective way of gaining a precise amount of space in mildly crowded cases with no apparent long-term damage to the teeth (see Fig. 7.19).

Moderate crowding

By timing extractions appropriately, significant alignment can result without active orthodontic treatment, especially if first premolars are being extracted to relieve labial segment crowding only. In the maxillary arch the canines often erupt buccally; if first premolars are removed as the canines erupt, they will move distally and erupt into the line of the arch. In the mandibular arch, if the canines are mesially angulated, removal of first premolars will allow some uprighting of the canines into the extraction spaces. This will relieve crowding in the labial segments and allow spontaneous alignment of labiolingually displaced teeth (Stephens, 1989). Rotated teeth are less likely to align without active treatment. All spontaneous alignment will occur in the first six months following extraction and after this, fixed appliances are often required to fully align the teeth. However, well-timed extractions can result in a shorter overall treatment duration and occasionally negate the need for further treatment.

Severe crowding

If the crowding is severe, extraction is almost always necessary and often in combination with anchorage support. This is most important in the maxillary arch where there is a greater tendency for the buccal teeth to move mesially and hence space to be lost. Various techniques for anchorage support are available and these are described in Chapter 5.

If more space is required than can be provided by the loss of premolars, not only does anchorage need to be supported but extra space will need to be created. This can be done by distalization of the buccal segments using extraoral traction or a temporary anchorage device (TAD), or occasionally by the extraction of more than one tooth per quadrant (Fig. 11.4).

Spacing

Tooth size–arch length discrepancy

The labial frenum has been considered to be a primary aetiological factor in the persistent midline diastema, due to the insertion of fibrous tissue into alveolar bone between the central incisors, and frenectomy suggested if the diastema is going to be closed (Edwards, 1977). However, this does not result in greater closure or a reduced potential for the diastema to reopen in the longer term following active treatment. Commonly, a frenum will remodel superiorly on closure of the space, and therefore if a frenectomy is performed, it can be carried out after the diastema is closed (Bergstrom et al, 1973; Shashua & Artun, 1999). For those cases where the frenum does not remodel and is unsightly or is causing problems, frenectomy is indicated. The closure of any diastema, irrespective of adjunctive surgical procedures, will be very prone to open up again after treatment and will require permanent retention.

Hypodontia

Maxillary lateral incisors

Space closure

When planning the substitution of a maxillary lateral incisor with a canine, this tooth may need to be adjusted to optimize the aesthetic result (Fig. 11.5) and there are several ways this can be achieved (Table 11.1). The first premolar distal to the canine should also be slightly rotated in a mesiopalatal direction to hide the palatal cusp and increase the amount of labial surface on show anteriorly to more accurately mimic a canine.

Table 11.1 Optimizing dental aesthetics when a maxillary canine is substituting for a lateral incisor

Space creation

Creating space for a missing maxillary lateral incisor will mean that the patient is reliant upon a prosthesis for the rest of their life and it is important that they understand the implications of this. Generally, the choice of prosthesis will be between an adhesive bridge or implant (Fig. 11.6). In the younger patient a simple denture or retainer incorporating the tooth can provide a useful temporary prosthesis. In patients where implant replacement is being considered, careful planning is required to ensure adequate bone and space are available (Table 11.2). Unless sufficient space already exists in the arch, space will actively need to be created. This usually involves fixed appliances and the use of compressed coil springs.

Table 11.2 Considerations when creating space for the implant replacement of missing teeth

| Care must be taken that adequate space is created between the roots of adjacent teeth. This invariably requires bodily movement and fixed appliances. In addition, enough bone must be present buccolingually. |

Mandibular second premolars

Generalized hypodontia

Where there is more than one missing tooth in each quadrant, treatment becomes more complex and will involve space redistribution with fixed appliances and prosthetic replacement of missing teeth. This treatment needs to be planned and executed within a multidisciplinary specialist team. Depending on how many teeth are missing and their position, anchorage management can be a problem, although recent advances in the use of temporary anchorage devices can help overcome this (Fig. 11.7). There is also an association between hypodontia and microdontia, meaning that existing teeth may require buildup to achieve the aesthetic and occlusal aims of treatment.

Anteroposterior problems

Increased overjet

Mechanotherapy for reducing an overjet

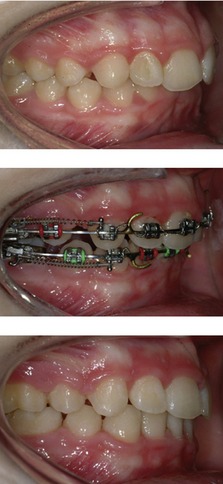

When using an edgewise bracket system the incisors are moved backwards bodily on a heavy rectangular wire. This can be done using space closing loops, although when using a preadjusted system, sliding mechanics are generally used. A stretched elastomeric module or nickel titanium coil spring is connected between the terminal molar and hooks situated on the archwire in the labial segment (Fig. 11.10). This will result in the archwire shortening as it slides through the brackets in the buccal segment and is often facilitated by the use of class II elastics. If anchorage has been correctly planned, bodily retraction of the incisors and a reduction in the overjet will take place. When using the Begg or Tip-Edge appliance the overjet is reduced early in treatment by tipping the teeth with light class II elastics (Fig. 11.10). The teeth are later uprighted using auxiliary springs.

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses