10 Management of the developing dentition

Early loss of deciduous teeth

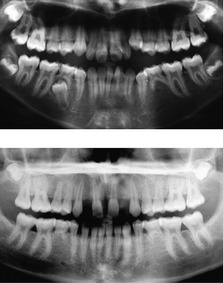

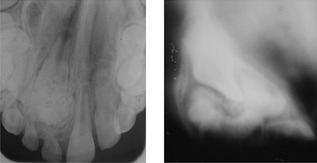

Figure 10.2 Crowding of maxillary second premolars as a result of early loss of the second deciduous molars.

The UL5 remains impacted in the palate whilst the UR5 has erupted palatally.

Balancing and compensating extractions

The decision to carry out a balancing or compensating extraction will depend upon a number of factors (Box 10.1). However, before the elective extraction of any deciduous tooth is instituted, a radiographic screen should be carried out to check for the presence, position and normal formation of the developing permanent dentition. Any other deciduous teeth of questionable prognosis should also be considered as candidates for balancing or compensating extraction, particularly if general anaesthesia is required. It can be more difficult to justify these extractions if local anaesthesia is used for the elective extraction of a single symptomatic tooth and cooperation for further extractions may be poor.

Box 10.1 Which deciduous teeth require balancing and compensating extractions?

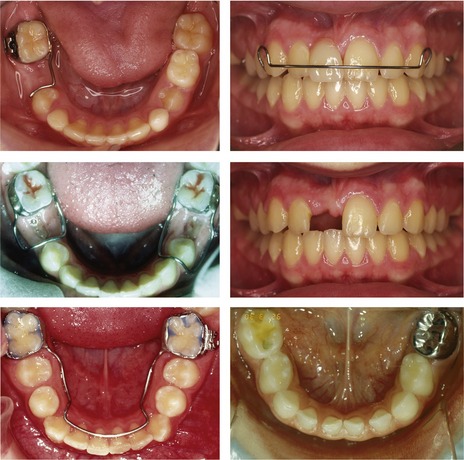

Space maintenance

A space maintainer is a removable or fixed orthodontic appliance that preserves space within the dental arches (Fig. 10.3). These appliances are most commonly used in the mixed dentition to prevent forward drift of the first permanent molars following early loss of deciduous second molar teeth, or to maintain space and serve as a prosthesis in the labial segment after traumatic loss of permanent incisors.

A space maintainer in the posterior dentition can be useful in the following situations:

It should always be remembered that a tooth is the ideal space maintainer and every effort should be made to preserve deciduous teeth until the time of their natural exfoliation (Fig. 10.3). If a space maintainer is to be used it should be in a mouth with good oral hygiene and ideally, a low risk of further caries. Unfortunately, cases requiring elective tooth extraction due to dental caries are often the least suitable for long-term space maintenance.

Prolonged retention of deciduous teeth

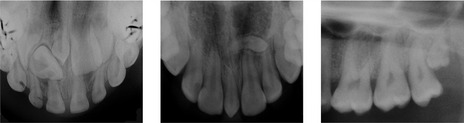

Occasionally a permanent successor will erupt having failed to resorb the roots of the overlying deciduous tooth (Fig. 10.4). The patient should be encouraged to exfoliate these retained deciduous teeth themselves and if this is not possible, they should be extracted under local anaesthetic.

Retained second deciduous molars

Treatment planning will depend primarily upon future space requirements for the correction of any underlying malocclusion and the long-term prognosis of the second deciduous molar. Clinical and radiographic examination of the crown, root and associated alveolar bone will give a useful indication of this (Fig. 10.5). Any of the following features, either alone or in combination, will demonstrate a potentially poor prognosis:

Figure 10.5 Retained deciduous molars in association with congenital absence of the second premolar.

Second deciduous molars can have an excellent long-term prognosis if they are in good condition and will match the lifespan of many prostheses. Indeed, if they survive to twenty years of age, continued long-term function can be anticipated (Bjerklin & Bennett, 2000; Sletten et al, 2003).

Ankylosis and infraocclusion

A tooth becomes ankylosed when the periodontal ligament is lost and direct fusion occurs between root dentine and the surrounding alveolar bone. Ankylosis most commonly affects deciduous molars, occurring in up to 9% of children (Kurol, 1981). A number of factors are thought to contribute:

A consequence of ankylosis can be the apparent ‘submergence’ or infraocclusion of the affected tooth relative to the occlusal plane (Fig. 10.6). This occurs in the growing child because alveolar bone and occlusal height increase with development, whilst the position of the ankylosed tooth remains fixed.

Hypodontia

The congenital absence of one or more teeth is a relatively common anomaly in human populations.

The term hypodontia is generally used to describe congenital tooth absence, but the definitions are actually quite specific (Fig. 10.7):

Nonsyndromic hypodontia

Within these clinical entities, certain teeth fail to develop more often than others:

Nonsyndromic hypodontia can be associated with other developmental anomalies affecting the dentition, which provides evidence of a genetic influence (Table 10.1). However, a multifactorial model has also been suggested (Brook, 1984), with the phenotypic effect being related to certain thresholds, themselves influenced by both genetic and environmental factors. Clearly, within this model, the mutation of a major gene may be a significant enough event to result in inherited tooth loss (Box 10.2).

Box 10.2 Candidate genes for nonsyndromic human hypodontia

Targeted deletion of many genes in mutant mice can disrupt tooth formation and these have provided a reference point in the search for candidate genes in human populations. However, given the large number of potential genes available, it is somewhat surprising that only three have been positively identified in human familial hypodontia (Cobourne, 2007):

Syndromic hypodontia

Congenital tooth absence is also seen in association with other recognizable structural defects or abnormalities (Table 10.2).

| Syndrome | Gene |

|---|---|

| Anhidrotic ectodermal dysplasia (OMIM 305100) | EDA |

| Adult (OMIM 103285) | TP73L |

| Ehlers Danlos (OMIM 225410) | ADAMTS2 |

| Incontinentia pigmenti (OMIM 308300) | NEMO |

| Limb mammary (OMIM 603543) | TP63 |

| Reiger (OMIM 180500) | PITX2 |

| Witkop (OMIM 189500) | MSX1 |

| Ellis–van Creveld (OMIM 225500) | EVC or EVC2 |

Management

The management of congenital tooth absence will involve either:

Milder forms of hypodontia can usually be managed within an orthodontic treatment plan in consultation with either the general dental practitioner or restorative specialist and is usually carried out in the permanent dentition (see Chapter 11). More severe hypodontia or oligodontia requires complex multidisciplinary treatment and is usually carried out within a specialist centre.

Supernumerary teeth

In common with hypodontia, supernumerary teeth also occur either as an isolated trait or as a manifestation of a clinical syndrome (Table 10.3), but they are usually classified according to morphology and location:

Table 10.3 Syndromic conditions associated with supernumerary teeth

| Syndrome | Gene |

|---|---|

| Cleft lip and palate | |

| Cleidocranial dysostosis (OMIM 119600) | RUNX2 |

| Gardner (OMIM 175100) | APC |

| Ellis–van Creveld (OMIM 225500) | EVC; EVC2 |

| Incontinentia pigmenti (OMIM 308300) | NEMO |

Box 10.3 Managing the mesiodens

The mesiodens is one of the commonest forms of supernumerary tooth and is often detected in the anterior maxilla as a chance radiographic finding. Whilst removal is indicated if they interfere with the eruption, position or proposed orthodontic movement of adjacent teeth, quite often they are asymptomatic and in these circumstances, they should be left alone (Kurol, 2006). The potential risks associated with leaving these teeth in situ, such as follicular enlargement, cystic formation and resorption of maxillary incisor roots, would appear to be small (Tyrologou et al, 2005). In addition, if the mesiodens subsequently erupts, it can be removed with a relatively simple extraction under local anaesthesia.

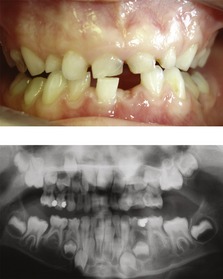

Figure 10.9 Extracted tuberculate supernumeraries and the effect of these teeth on the developing dentition.

Figure 10.10 Erupted tuberculate supernumerary.

The URA has been exfoliated and the UR1 is unlikely to erupt whilst the supernumerary is in situ.

Figure 10.13 Complex odontome in the anterior maxilla.

The Scanora view on the right reveals the full extent of the odontome overlying the UR1.

Abnormalities of tooth size

Abnormalities of tooth form

Figure 10.18 Double incisor teeth in the deciduous dentition with minor (left) and marked (right) coronal notching.

Right panel courtesy of Rudi Keane.

Abnormalities of eruption

A number of systemic conditions are associated with delayed eruption and these can affect both dentitions (Table 10.4). In the permanent dentition, great individual variation can exist in the timing of tooth eruption, with symmetrical deviation of anything up to two years from the mean not necessarily being a cause for concern. In the majority of children, local factors will be the main cause of any eruption disturbances that do occur (Table 10.5).

Table 10.4 Systemic conditions associated with delayed tooth eruption

Table 10.5 Local factors causing disturbances of tooth eruption

Primary management relies upon ensuring adequate space exists in the dental arch to accommodate the unerupted tooth and removing any potential obstruction. In these circumstances, the majority of teeth will erupt. If this fails to happen, or the unerupted tooth is ectopic from its normal path of eruption, surgical exposure, with or without orthodontic traction, may be required to accommodate the affected tooth into the dental arch (Box 10.4).

Box 10.4 Surgical exposure of impacted teeth

Impacted teeth are surgically exposed using one of two basic techniques:

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses