Anticoagulants and antiplatelet agents are increasingly being used for primary and secondary prophylaxis in patients with cardiovascular and cerebrovascular thromboembolic disease and venous thromboembolism. In the United States, it is estimated that 2.3 million patients suffer from atrial fibrillation and that 40% of these patients are receiving anticoagulation therapy. Many clinicians still favor the practice of reducing or temporarily discontinuing use of the anticoagulation agent before any surgical intervention. Management of these patients is a balancing act between maintaining surgical and postsurgical hemostasis and minimizing risk for an embolic event. The most common causes of atrial thromboembolism are valvular heart disease and atrial fibrillation. The risk for arterial thromboembolism in patients with atrial fibrillation is 1% per year for those without any other co-morbid conditions and 17% per year for those older than 75 years. Furthermore, nearly 20% of these arterial thromboemboli are fatal in patients with atrial fibrillation. The average rate of such embolic events is reduced by 66% in patients with atrial fibrillation and by 75% in patients with mechanical heart valves with the use of anticoagulation therapy. Thus, there must be an evidence-based rationale for temporarily discontinuing anticoagulation therapy in any patient because of the risk for catastrophic embolic complications.

The most current guidelines all favor continuing anticoagulation therapy during minor surgical procedures. This is based on the belief that the risk for “significant bleeding” in patients taking oral anticoagulants with a stable international normalized ratio (INR) of 1.5 to 4 is very low in comparison to the risk for a thromboembolic event as a result of cessation of the use of the anticoagulant agent. The effects of thrombotic events on systemic health should never be taken lightly; for example, embolic strokes result in a significant neurologic deficit or death in 70% of patients, and thrombosis in a patient with a mechanical heart valve is fatal in 15% of cases. Consequently, clinicians should base their decision to discontinue a patient’s anticoagulation on solid medical evidence rather than relying on anecdotal evidence or fear of a particular clinical complication (postoperative bleeding).

Warfarin sodium (Coumadin), which was initially marketed as a pesticide against rats and mice, is the most commonly used anticoagulation agent. The mechanism of its action is as follows: warfarin competitively inhibits the enzyme epoxide reductase, which converts the reduced form of vitamin K to the active vitamin K epoxide. By inhibiting epoxide reductase, warfarin diminishes available vitamin K in tissues, which serves as a co-enzyme for glutamyl carboxylase. This is the enzyme that is responsible for the carboxylation of coagulation factors, specifically clotting factors II, VII, IX, and X and endogenous proteins C and S.

Management of an anticoagulated patient is a topic of great significance to the oral and maxillofacial surgeon inasmuch as postoperative hemostasis is a fundamental patient management issue. Additionally, as the population ages, the practitioner will encounter this particular group of patients at an increasing incidence. Therefore, this chapter will focus on the general principles of management of patients who are receiving anticoagulant and antiplatelet therapy and undergoing oral surgical procedures.

Etiopathogenesis/Causative Factors

Several conditions are associated with an increased likelihood for a thromboembolic event, such as the presence of a mechanical heart valve or a history of stroke ( Box 26-1 ). Therefore, the clinician should stratify these patients into high risk, moderate risk, and low risk for experiencing a thromboembolic event by not receiving anticoagulation therapy. Such stratification is based on the type of prosthetic valve, the patient’s age, the presence of atrial fibrillation, existing co-morbid conditions, and history of stroke or a thrombotic event. Patients should be stratified according to their risk for thromboembolism rather than being stratified according to the invasiveness of the surgical procedure. Although patients undergoing major reconstructive procedures are obviously at greater risk for postoperative bleeding than those undergoing minor dentoalveolar procedures, regardless of the complexity and invasiveness of the operation being performed, all patients should be properly assessed regarding their risk for thromboembolism. Based on the American College of Chest Physicians (ACCP) guidelines for all the conditions listed in Box 26-1 , older-generation aortic valve prostheses, mitral valve prostheses, and a history of transient ischemic attack within the past 6 months pose the greatest risk for thromboembolism (>10%). Patients considered to be within the moderate-risk category have a 4% to 10% per year incidence of thromboembolism, whereas patients in the low-risk category have less than a 4% per year incidence of thromboembolism.

High Risk

- •

DVT within the past 1 to 3 months

- •

CVA or TIA within the past 6 months

- •

Any type of mitral valve prosthesis or older aortic prosthesis

Moderate Risk

- •

DVT within the past 3 to 12 months

- •

Active cancer

- •

Bileaflet aortic valve prosthesis with risk factors (AF, CHF, HTN, DM, >75 years of age)

Low Risk

- •

Singe DVT event more than 12 months previously with no other risk factors

- •

Bileaflet aortic valve prosthesis without risk factors (AF, CHF, HTN, DM, >75 years of age)

AF , atrial fibrillation; CHF , congestive heart failure; CVA , cerebrovascular accident; DM , diabetes mellitus; DVT , deep venous thrombosis; HTN , hypertension; TIA , transient ischemic attack.

Diagnostic Studies

Before any laboratory study, a thorough review of the patient’s medical history should be carried out. The history should focus on the patient’s bleeding history and current medications. A quick examination of the upper extremities can be done to rapidly check for ecchymoses, a finding indicative of a potentially anticoagulated state. Likewise, asking simple questions (“when you cut yourself shaving, how long does it take you to stop bleeding”) can also easily inform the clinician of potential risk for bleeding. It is important to also ask about the use of herbal supplements; for example, St. John’s wort interacts with warfarin and causes a reduction in warfarin’s anticoagulation effect.

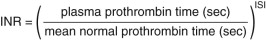

Laboratory assessment of an anticoagulated patient should include hemoglobin, hematocrit, partial thromboplastin time, prothrombin time (PT), and the INR. The World Health Organization (WHO) Committee on Biological Standards introduced the INR in 1983 to provide clinicians with a more standardized assessment tool for patients receiving anticoagulation therapy. The INR was developed to standardize the PT. The PT test is based on the sensitivity of various thromboplastins; it is a test of the intrinsic clotting cascade and is the test used to monitor patients taking warfarin. The INR is calculated by comparing the patient’s PT with that of a mean of 20 fresh plasma samples from healthy ambulatory patients while using the international sensitivity index to correct for the sensitivity of the various thromboplastins that a laboratory might use ( Fig. 26-1 ). According to the WHO calibration recommendations, laboratory variation is usually within the range of 4%. In summary, the INR value should be independent of the laboratory used to measure the INR. With regard to what is an acceptable INR range, there exists a great deal of debate.

Diagnostic Studies

Before any laboratory study, a thorough review of the patient’s medical history should be carried out. The history should focus on the patient’s bleeding history and current medications. A quick examination of the upper extremities can be done to rapidly check for ecchymoses, a finding indicative of a potentially anticoagulated state. Likewise, asking simple questions (“when you cut yourself shaving, how long does it take you to stop bleeding”) can also easily inform the clinician of potential risk for bleeding. It is important to also ask about the use of herbal supplements; for example, St. John’s wort interacts with warfarin and causes a reduction in warfarin’s anticoagulation effect.

Laboratory assessment of an anticoagulated patient should include hemoglobin, hematocrit, partial thromboplastin time, prothrombin time (PT), and the INR. The World Health Organization (WHO) Committee on Biological Standards introduced the INR in 1983 to provide clinicians with a more standardized assessment tool for patients receiving anticoagulation therapy. The INR was developed to standardize the PT. The PT test is based on the sensitivity of various thromboplastins; it is a test of the intrinsic clotting cascade and is the test used to monitor patients taking warfarin. The INR is calculated by comparing the patient’s PT with that of a mean of 20 fresh plasma samples from healthy ambulatory patients while using the international sensitivity index to correct for the sensitivity of the various thromboplastins that a laboratory might use ( Fig. 26-1

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses