Ludwig’s angina is a term for a rapidly progressive cellulitis of the floor of the mouth and neck with induration and bilateral submandibular, sublingual, and submental space involvement with an infectious process; dysphagia and respiratory obstruction may ensue. Typically no abscess or lymphadenopathy is seen in the classic description, but progression to abscess formation within the involved space and contiguous spaces is most often the case. Angina derives from the Latin term angere , meaning “to strangle.” Grodinsky stated in a 1939 paper that Ludwig’s angina was a unique deep neck abscess characterized by (1) occurrence bilaterally in more than one space, (2) production of gangrenous serosanguineous infiltration with or without pus, (3) involvement of connective tissue and muscle but not glandular structures, (4) spread by continuity, not via lymphatics. The eponymous condition named after Wilhelm Frederick von Ludwig may have been the cause of the author’s own death, because he died at the age of 75 years, days after developing an inflammation of the neck. It should be noted that the early descriptions of the condition were based on clinical and necropsy findings of patients whose fate “despite the most skillful therapy is almost always fatal.” Mortality and morbidity associated with the condition are greatly reduced in the modern era of antibiotics, improved imaging, and airway management.

Etiopathogenesis

The most common cause of Ludwig’s angina is odontogenic. More specifically the lower second and third molars are implicated because their roots extend below the mylohyoid muscle, and periapical abscesses of these teeth result in lingual cortical penetration with an ensuing submandibular infection. The submandibular space is subdivided into the sublingual space above the mylohyoid and the submaxillary space below it. These two divisions freely communicate with each other over the posterior border of the digastric muscle. The submandibular space communicates with the submental space anteriorly past the anterior belly of the digastric muscle. Ludwig’s angina, when critically reviewed using modern diagnostic and imaging techniques, anaerobic cultures, and contemporary patient management protocols, is not distinct from other space infections. It is, in fact, an extensive spread of infection throughout the mouth floor and neck caused by the same organisms responsible for less morbid head and neck infections. Although Ludwig’s angina is odontogenic in up to 90% of cases, oral lacerations, mandible fracture, infections of oral malignancy, and bilateral sialolithiasis-related submandibular gland infection have also been implicated. The bacterial isolates of Ludwig’s angina are varied, but are mostly aerobes and anaerobes, including α-hemolytic streptococci, staphylococci, and bacteroides. In addition, other anaerobes such as peptostreptococci, peptococci, Fusobacterium nucleatum , Viellonella species, and spirochetes have also been isolated in cultures from patients with Ludwig’s angina. Gram-negative organisms such as Neisseria catarrhalis, Escherichia coli, Pseudomonas aeruginosa , and Haemophilus influenzae have also been reported. A recent article reported a fatal case of Ludwig’s angina associated with Gemella morbillorum , a facultative anaerobic organism. In summary most deep neck infections are caused by oral flora and most are polymicrobial, of which 75% are obligate anaerobes. Results of blood cultures from patients with Ludwig’s angina are generally negative.

Pathologic Anatomy

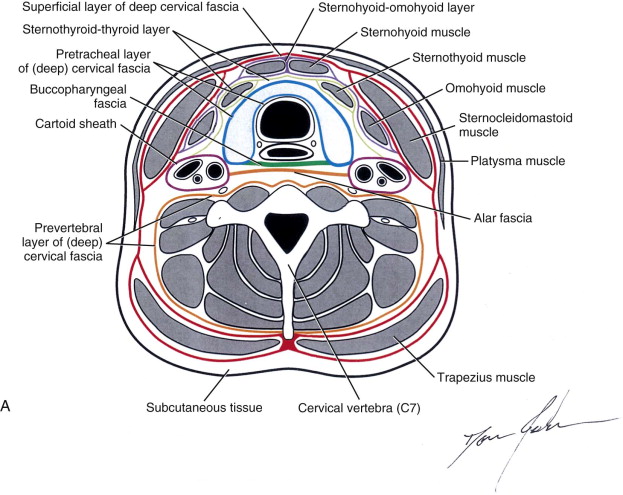

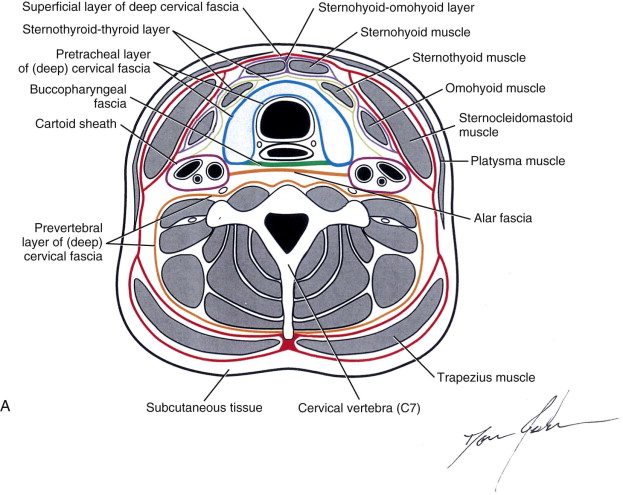

To adequately treat Ludwig’s angina, the anatomy of the fascial spaces of the neck where the infection is contained and where it may spread must be thoroughly understood. Fascia is a band of connective tissue that surrounds structures (e.g., muscles) and by its nature of layering gives rise to potential spaces that allow for the spread of infection. The superficial fascia is located immediately deep to the skin. It contains fat and is continuous from the base of the neck into the face; that is, it traverses the length of the face and neck. Infections in this space are superficial and easily observed early on. The deep cervical fascia lies deep to the superficial fascia under the platysma muscle.

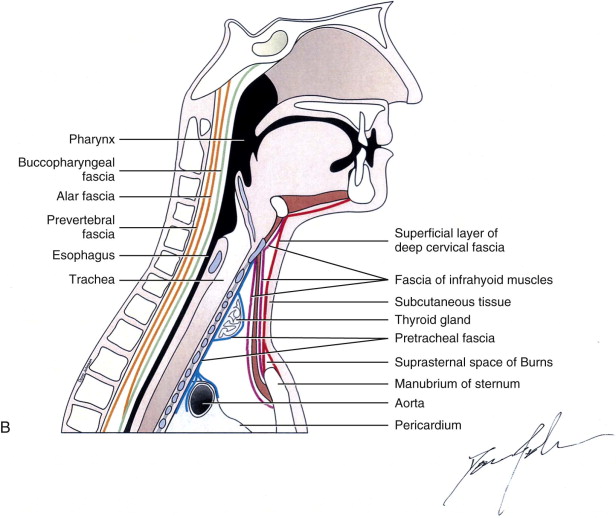

The deep cervical fascia assists muscle movement because it limits the muscle volume contained within, it provides attachments for some muscles, and it also encloses nerves and blood vessels. It is subdivided in the neck into four layers ( Box 118-1 ). An understanding of these divisions is at the heart of the knowledge necessary for effective infection management. The superficial layer of the deep cervical fascia lies immediately deep to the superficial fascia and platysma muscle. It encircles the neck completely, and as it approaches the sternocleidomastoid and trapezius muscles, it splits to lie on their superficial and deep surfaces. It is attached anteriorly to the chin, hyoid bone, and sternum. Posteriorly it attaches to the spinous processes of the cervical vertebrae. Superiorly it attaches to the occipital protuberance, superior nuchal line, mastoid process, inferior border of the zygomatic arch, and the inferior border of the mandible from the angle to the midline ( Fig. 118-1 ). Inferiorly it attaches to the sternum where it splits into anterior and posterior parts, and it also attaches to the clavicle and the acromium of the scapula.

- 1

Superficial layer of the deep cervical fascia (investing layer)

- 2

Middle layer of the deep cervical fascia

- 3

Deep layer of the deep cervical fascia

- 4

Carotid sheath (made up of all three layers of the deep cervical fascia)

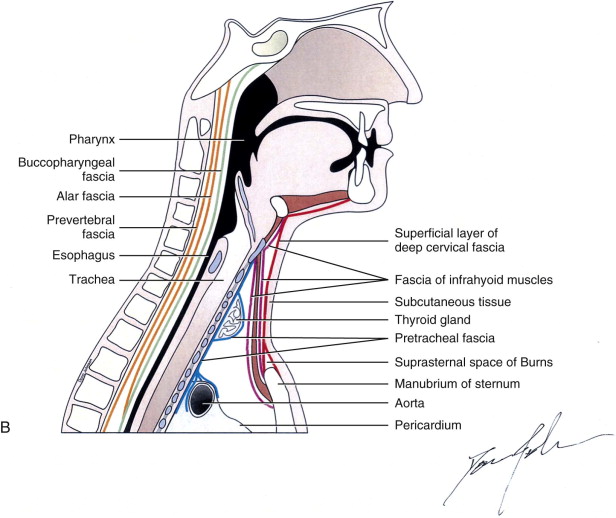

The middle layer of the deep cervical fascia consists of a muscular portion , which surrounds the strap muscles; a visceral portion or buccopharyngeal portion , which lies deep to the superficial layer of the deep cervical fascia posterior to the pharynx; and a pretracheal layer , which covers the thyroid gland, esophagus, and trachea. The muscular portion attaches superiorly at the hyoid bone and thyroid cartilage, and inferiorly at the medial sternum. The visceral portion of the middle layer of the deep cervical covers the muscular layer of the pharynx and is continued forward onto the buccinator muscle. It lies posterior to the pharynx and is attached to the base of the skull above, and then runs inferiorly into the mediastinum where it fuses with the alar fascia (see later). The pretracheal layer attaches superiorly to the larynx and inferiorly into the fibrous pericardium in the superior mediastinum and encircles the thyroid gland (see Fig. 118-1 ).

The deep layer of the deep cervical fascia consists of a prevertebral layer and the alar fascia. The prevertebral layer of the deep cervical fascia completely encircles the cervical portions of the prevertebral muscles and the postvertebral muscles. It is attached above at the skull base and inferiorly at the coccyx. The alar fascia is a portion of the prevertebral fascia found between the middle layer of the deep cervical fascia and the prevertebral layers of the deep cervical fascia. It is attached above at the base of the skull, and inferiorly it fuses with the visceral portion of the middle layer of the deep cervical fascia at the level of T2. The alar fascia separates the retropharyngeal space from the “danger space.” The danger space is a subdivision of the retropharyngeal space, extending from the base of the skull to the level of the diaphragm; it provides a route for the spread of infection from the pharynx to the mediastinum.

The carotid sheath, which contains the carotid artery, the internal jugular vein, and the vagus nerve, is enclosed within a sheath composed of contributions from the superficial, middle, and deep layers of the deep cervical fascia. It is attached above to the base of the skull and merges below with tissues surrounding the aortic arch.

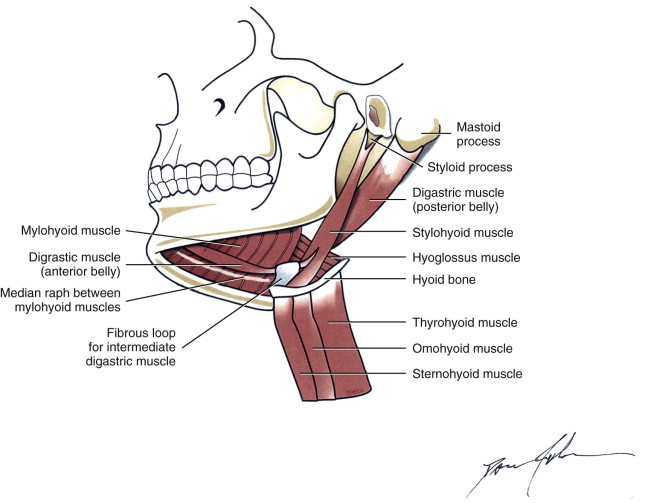

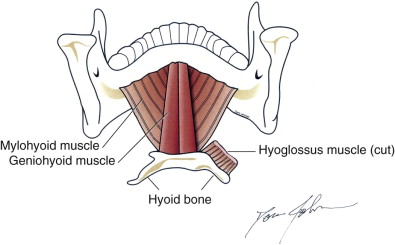

The submandibular space is composed of two potential spaces that span the region from the mucosa of oral cavity to the superficial layer of the deep cervical fascia. It encloses the area between the mandible and the hyoid bone ( Fig. 118-2 ). The mylohyoid muscle originates on the mylohyoid line on the lingual surface of the mandible and inserts on the symphysis menti, the mylohyoid raphe, and the body of the hyoid bone posteriorly. This muscle horizontally divides the submandibular space into the sublingual space above (supramylohyoid compartment) and the submandibular or submaxillary space below (inframylohyoid compartment) ( Fig. 118-3 ). Most refer to the combined space as the submandibular space, whose two components communicate freely along the posterior aspect of the mylohyoid muscle. The supramylohyoid compartment of the submandibular space contains loose areolar tissue, sublingual glands, submandibular glands, Wharton duct, the lingual artery and vein, geniohyoid muscles, and the lingual and hypoglossal nerves. The inframylohyoid compartment contains the anterior bellies of the digastric muscles, submandibular glands, lymph nodes, and the facial artery and vein. The portion of the inframylohyoid compartment confined between the anterior bellies of the digastric muscles is referred to as the submental space (see Fig. 118-2 ). Infections involving the submental and sublingual spaces can result in elevation and protrusion of the tongue, which compromises the airway. The submandibular space communicates freely with the lateral pharyngeal space and by extension the retropharyngeal space. From the retropharyngeal space, which lies between the buccopharyngeal layer of the middle layer of the deep cervical fascia covering the pharynx and esophagus and the anterior alar fascia (see Fig. 118-1 ), infections can spread into the danger space by perforation. The danger space, which lies posterior to the alar fascia and where the alar fascia and the middle layer of the cervical fascia fuse and anterior to the prevertebral fascia, extends from the base of the skull to the diaphragm. This is the pathway for mediastinal and lung involvement with neck infections. The carotid sheath is another pathway for infection from the submandibular space to spread to the mediastinum (see Fig. 118-1 ).

Pathologic Anatomy

To adequately treat Ludwig’s angina, the anatomy of the fascial spaces of the neck where the infection is contained and where it may spread must be thoroughly understood. Fascia is a band of connective tissue that surrounds structures (e.g., muscles) and by its nature of layering gives rise to potential spaces that allow for the spread of infection. The superficial fascia is located immediately deep to the skin. It contains fat and is continuous from the base of the neck into the face; that is, it traverses the length of the face and neck. Infections in this space are superficial and easily observed early on. The deep cervical fascia lies deep to the superficial fascia under the platysma muscle.

The deep cervical fascia assists muscle movement because it limits the muscle volume contained within, it provides attachments for some muscles, and it also encloses nerves and blood vessels. It is subdivided in the neck into four layers ( Box 118-1 ). An understanding of these divisions is at the heart of the knowledge necessary for effective infection management. The superficial layer of the deep cervical fascia lies immediately deep to the superficial fascia and platysma muscle. It encircles the neck completely, and as it approaches the sternocleidomastoid and trapezius muscles, it splits to lie on their superficial and deep surfaces. It is attached anteriorly to the chin, hyoid bone, and sternum. Posteriorly it attaches to the spinous processes of the cervical vertebrae. Superiorly it attaches to the occipital protuberance, superior nuchal line, mastoid process, inferior border of the zygomatic arch, and the inferior border of the mandible from the angle to the midline ( Fig. 118-1 ). Inferiorly it attaches to the sternum where it splits into anterior and posterior parts, and it also attaches to the clavicle and the acromium of the scapula.

- 1

Superficial layer of the deep cervical fascia (investing layer)

- 2

Middle layer of the deep cervical fascia

- 3

Deep layer of the deep cervical fascia

- 4

Carotid sheath (made up of all three layers of the deep cervical fascia)

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses